Algeria, Vietnam, Iraq and the Conscience of the Intellectual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

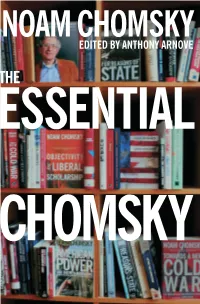

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

Extensions of Remarks

32254 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 23, 19 7 6 before the Senate, I move, in accordance CONFffiMATIONS ject to the nominee's commitment to respond with the previous order, that the Senate to requests to appear and testify before any Executive nominations confirmed by duly constituted committee of the Senate. stand in adjournment until the hour of the Senate September 23, 1976: THE JUDICIARY 9 a.m. tomorrow. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION AND Howard G. Munson, of New York, to be The motion was agreed to; and at 8: 03 WELFARE U.S. district judge for the northern district p.m., the Senate adjourned until tomor Susan B. Gordon, of New Mexico, to be an of New York. Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Vincent L. Broderick, of New York to be row, Friday, September 24, 1976, at 9 Welfare. U.S. district judge for the southern dtstrict a.m. The above nomination was approved sub- of New York. EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS THE POLISH NATIONAL ALLIANCE Toastmaster, Felix Mika. attractive for advertisers to distribute their OF YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO Introduction of, Jack c. Hunter, Mayor, brochures unaddressed, as newspaper sup Youngstown, Ohio. • plements for instance, than to distribute Introduction of guests, Toastmaster. them separately to specific people or ad HON. CHARLES J. CARNEY Presentation of honoree, Mary C. Grabow dresses. OF 01!110 ski, Commissioner District 9, PNA. "Our members should be able to use pri Main speaker, Aloysius A. Mazewski, Presi vate delivery companies to deliver advertis IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES dent PNA. ing material just as can be done for maga Thursday, September 23, 1976 Presentation of deb't~tantes, Mary C. -

A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael

South Carolina Law Review Volume 62 Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2010 A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael Lonnie T. Brown Jr. University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lonnie T. Brown, Jr., A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael, 62 S. C. L. Rev. 1 (2010). This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brown: A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Select A TALE OF PROSECUTORIAL INDISCRETION: RAMSEY CLARK AND THE SELECTIVE NON-PROSECUTION OF STOKELY CARMICHAEL LONNIE T. BROWN, JR.* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 II. THE PROTAGONISTS .................................................................................... 8 A. Ramsey Clark and His Civil Rights Pedigree ...................................... 8 B. Stokely Carmichael: "Hell no, we won't go!.................................. 11 III. RAMSEY CLARK'S REFUSAL TO PROSECUTE STOKELY CARMICHAEL ......... 18 A. Impetus Behind Callsfor Prosecution............................................... 18 B. Conspiracy to Incite a Riot.............................................................. -

Annual Giving

ANNUAL GIVING 2016-2017 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT GIVING IN REVIEW Dear Generous Benefactors, 2016 - 2017 It is my privilege to report on a few highlights of what your generosity enabled us to July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 accomplish this year. The 2016-17 annual giving year saw a few records set and many enhancements to the educational experience of our Dons. The Loyola Fund Unrestricted & Designated $2,227,693 33% I continue to be humbled by the extraordinary generosity that you bestow upon the Endowed Scholarship Gifts $1,562,963 49% Loyola Blakefield community. Leading the way in support of our mission not only Capital Projects Support $523,444 The Annual Fund invests in the formation of our Dons, but inspires others to follow in your charitable 11% Blue & Gold Auction - Net Proceeds $386,718 Endowed Scholarships footsteps. 7% Capital Projects Support Let’s continue to partner with one another to create more opportunities for our Dons $4,700,818 Blue & Gold Auction to grow in their faith, conquer intellectual pursuits, and learn the value of serving others. With gratitude, ALUMNI GIVING Mr. Anthony I. Day P ’15, ’19vt month TOTAL GIFTS* President JUNE OF ALL ALUMNI 17.4% MADE A GIFT TOP 5 CLASSES $4.7 participation dollars raised million 1953 71% 1978 $352,140 1947 & 1954 42% 1982 $177,599 1949 & 1955 38% 1963 $158,580 RECORD 1960 35% 1964 $121,922 LOYOLA FUND 1952 & 1965 33% 1957 $107,515 $2.6 million BREAKING campaignFAMILY GIVING YEAR FY FY FACULTY, STAFF, AND BOARD THANK YOU TO ALL OF OUR 2016 48% 55% 2017 OF TRUSTEES GIVING DONORS AND VOLUNTEERS PERCENT PARTICIPATION BY CLASS PARTICIPATION CLASS OF 2017 43% CLASS OF 2021 62% * Every effort has been made to include all donors to Loyola Blakefield whose gifts were CLASS OF 2018 47% CLASS OF 2022 73% received between July 1, 2016 and June 30, 2017. -

Freedom Quotes, May 2015 May 1. Freedom Is Not Worth Having If It

Freedom Quotes, May 2015 May 1. Freedom is not worth having if it does not include the freedom to make mistakes. Mahatma Ganhdi May 2. When a man is denied the right to live the life he believes in, he has no choice but to become an outlaw. Nelson Mandela May 3. The most important kind of freedom is to be what you really are. You trade in your reality for a role. There can’t be any large-scale revolution until there’s a personal revolution, on an individual level. It’s got to happen inside first. Jim Morrison May 4. Freedom lies in being bold. Robert Frost May 5. People demand freedom of speech as a compensation for the freedom of thought they seldom use. Soren Kierkegaard May 6. Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves. Abraham Lincoln May 7. I am free, no matter what rules surround me. If I find them tolerable, I tolerate them; if I find them too obnoxious, I break them. I am free because I know that I alone am morally responsible for everything I do. Robert A. Heinlein May 8. If we don’t believe in freedom of expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all. Noam Chomsky May 9. Freedom is nothing else but a chance to be better. Albert Camus May 10. ---To be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others. Nelson Mandela May 11. -

Page 1 of 5 Benjamin Spock Conspiracy 7/25/2009

Benjamin Spock Conspiracy Page 1 of 5 excerpt from It Did Happen Here by Bud and Ruth Schultz (University of California Press, 1989) The Conspiracy to Oppose the Vietnam War, Oral History of Benjamin Spock The Selective Service Act of 1948 made it a criminal offense for a person to knowingly counsel, aid, or abet someone in refusing or evading registration in the armed forces. In 1968, Dr. Benjamin Spock and four others were indicted for conspiring to violate this act. Evidence of the conspiracy was to be found in the public expressions of the defendants: hours of selectively edited newsreel footage of press conferences, demonstrations, and public addresses they made in opposition to government policy in Vietnam. What could better symbolize the damage such prosecutions made on the free marketplace of ideas? Why were they charged with conspiracy to counsel, aid, and abet rather than with the commission of those acts themselves? Conspiracy, Judge Learned Hand said, is "the darling of the modern prosecutor's nursery."' It relaxes ordinary rules of evidence, frequently results in higher penalties than the substantive crime, may extend the statue of limitations, and holds all conspirators responsible for the acts of each. The conspirators may have acted entirely in the open, they may never have met; they may have agreed only implicitly; they may never have acted illegally. It's enough that they were of a like mind to do so. When applied to political activity, writing, and speech, a conspiracy charge has virtually no limits. Government attorneys could have included as co-conspirators the publishers of Dr. -

Merchants of Death” Survive and Prosper

February, 2018 Vol. 47 No. 1 Jewish Peace Letter Published by the Jewish Peace Fellowship CONTENTS F-35A Lightning II Lawrence Witner Merchants Pg. 5 of Death Susannah Sexual Heschel Assaults Pg.3 & Harass- ments & American Jews Some Sug- gestions for Liberal Zion- ists and for Progressive Jews Who Are Not Patrick Henry What Ken Burns and Pg. 3 Lynn Novick’s The Vietnam War Completely Missed: The Interfaith Anti- war Movement Hush, Hush, Murray Polner When One Person Pg. 6 Can Decide If We Live or Die. 2 • February, 2018 jewishpeacefellowship.org Questions we must ask Susannah “What is a religious Heschel person? A person who is maladjusted; attuned to the agony of others; aware of God’s presence and of God’s needs; a religious person is never satisfied, but always questioning, striving for something deeper, and always refusing to accept inequalities, the status quo, the cruelty and suffering of others.” Sexual Assaults & Harassments & American Jews hock and horror over individual cases of serial sexual harassers and assault- ers is just beginning and should not be a tool for ignoring the bigger problem that sexual harassment is used to prevent women from attaining their professional goals. S Yes, a few rabbis have spoken about the is- sue from the pulpit—and I admire them enor- mously—but this is an issue that should be addressed more widely within the Jewish community. So let us ask why so few women hold positions of leadership in Jew- Let us ask why ish communal organizations. Let us ask why I am still invited so few women to speak at conferences where I am hold positions the only woman on the program. -

Kennethj. Heineman Ohio University-Lancaster

REFORMATION: MONSIGNOR CHARLES OWEN RICE AND THE FRAGMENTATION OF THE NEW DEAL ELECTORAL COALITION IN PITTSBURGH, 1960-1972 Kennethj. Heineman Ohio University-Lancaster he tearing apart of the New Deal electoral coalition in the i96os has attracted growing scholarly and media attention. Gregory Schneider and Rebecca Klatch emphasized the role collegiate lib- ertarians played in moving youths to the Right. Rick Perlstein, focusing on conservatives who came of age during World War II, argued that the New Right wedded southern white racism to midwestern conspiracy-obsessed anti-Communism. For his part, Dan Carter contended that Alabama governor George Wallace's racist politics migrated north where they found a receptive audi- ence in urban Catholics.' Samuel Freedman chronicled the ideological evolution of sev- eral generations of northern Catholics as they moved into the GOP in reaction to black protest, mounting urban crime, and the Vietnam War. Ronald Formisano, Jonathan Rieder, and Thomas Sugrue, in their studies of Boston, New York, and Detroit, respectively, gave less attention to the Vietnam War, emphasizing the racial attitudes of working-class Catholics and unionists. In PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY: A JOURNAL OF MID-ATLANTIC STUDIES, VOL. 7 1, NO. I, 2004. Copyright © 2004 The Pennsylvania Historical Association PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY their surveys of the relationship between Catholics and blacks, John McGreevy and Gerald Gamm argued that urban Catholics frequently did not respond well to blacks. 2 Ronald Radosh and Steven Gillon took a different tack from Carter, Gamm, and Sugrue. In their studies of the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), an organization that anti-Communist Democrats such as Minneapolis mayor Hubert Humphrey had helped create in I947, Radosh and Gillon examined the middle-class activists who rejected America's anti-Communist foreign policy and the racial conservatism of many unionists. -

Jessica Mitford

Jessica Mitford: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Title Jessica Mitford Papers Dates: 1949-1973 Extent 67 document boxes, 3 note card boxes, 7 galley files, 1 oversize folder (27 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, printed material, reports, notes, interviews, manuscripts, legal documents, and other materials represent Jessica Mitford's work on her three investigatory books and comprise the bulk of these papers. Language English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1973 Processed by Donald Firsching, Amanda McCallum, Jana Pellusch, 1990 Repository: Harry Ransom Center University of Texas at Austin Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Biographical Sketch Born September 11, 1917, in Batsford, Gloucestershire, England, Jessica Mitford is one of the six daughters of the Baron of Redesdale. The Mitfords are a well-known English family with a reputation for eccentricity. Of the Mitford sisters, Nancy achieved notoriety as a novelist and biographer. Diana married Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the British fascists before World War II. Unity, also a fascist sympathizer, attempted suicide when Britain and Germany went to war. Deborah became the Duchess of Devonshire. Jessica, whose political bent ran opposite to that of her sisters, ran away to Loyalist Spain with her cousin, Esmond Romilly, during the Spanish Civil War. Jessica eventually married Romilly, who was killed during World War II. In 1943, Mitford married a labor lawyer, Robert Treuhaft, while working for the Office of Price Administration in Washington, D.C. The couple soon moved to Oakland, California, where they joined the Communist Party. In California, Mitford worked as executive secretary for the Civil Rights Congress and taught sociology at San Jose State University. -

Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler a Dissertati

Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Chair Ann Anagnost Stevan Harrell Danny Hoffman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology ©Copyright 2018 Darren T. Byler University of Washington Abstract Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Department of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies This study argues that Uyghurs, a Turkic-Muslim group in contemporary Northwest China, and the city of Ürümchi have become the object of what the study names “terror capitalism.” This argument is supported by evidence of both the way state-directed economic investment and security infrastructures (pass-book systems, webs of technological surveillance, urban cleansing processes and mass internment camps) have shaped self-representation among Uyghur migrants and Han settlers in the city. It analyzes these human engineering and urban planning projects and the way their effects are contested in new media, film, television, photography and literature. It finds that this form of capitalist production utilizes the discourse of terror to justify state investment in a wide array of policing and social engineering systems that employs millions of state security workers. The project also presents a theoretical model for understanding how Uyghurs use cultural production to both build and refuse the development of this new economic formation and accompanying forms of gendered, ethno-racial violence. -

Simone De Beauvoir and the Politics of Privilege

Simone de Beauvoir and the Politics of Privilege SONIA KRUKS How should socially privileged white feminists (and others) address their privilege? Often, individuals are urged to overcome their own personal racism through a politics of self-transformation. The paper argues that this strategy may be problematic, since it rests on an over-autonomous conception of the self. The paper turns to Simone de Beauvoir for an alternative account of the selh as “situated,” and explores what this means for a politics ofprivilege. In 1955, Simone de Beauvoir published a collection of essays entitled Privil&es. She wrote in the Preface that one question linked all her essays together: how may the privileged think about their situation? They cannot think about it honestly and without self-delusion, she says. For, “to justify the possession of particular advantages in the mode of the universal is not an easy undertaking,” and it results in a mode of thought marked by the kinds of obfuscation and self- deception that Beauvoir (along with Jean-Paul Sartre) calls “bad faith” (1955, 7). Beauvoir’s main concern in her book was with how ruling-class privilege is masked, or rationalized, in thought. However, her critique also resonates strongly with recent feminist critiques of the self-deceptions inherent in mas- culine, white-race, and other forms of privilege, as well as with the dilemmas of privileged would-be progressives’ more generally. In this paper I turn to Simone de Beauvoir to help think about ‘privilege’ as it is conceived in feminist theory and politics today, and particularly as it poses a predicament for those who enjoy significant social privilege while also being committed to fighting it. -

Vietnam War on Trial: the Court-Martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 1994 Vietnam War on Trial: The Court-Martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy Robert N. Strassfeld Case Western Reserve University - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons Repository Citation Strassfeld, Robert N., "Vietnam War on Trial: The Court-Martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy" (1994). Faculty Publications. 551. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/551 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. TilE VIETNAM WAR ON TRIAL: TilE COURT-MARTIAL OF DR. HOWARD B. LEVY ROBERT N. STRASSFELD• This Article examines the history of a Vietnam War-era case: the court-martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy. The U.S. Army court-martialled Dr. Levy for refusing to teach medicine to Green Beret soldiers and for criticizing both the Green Berets and American involvement in Vietnam. Although the Supreme Court eventually upheld Levy's convicti on in Parkerv. Levy, ill decision obscures the political content of Levy's court-martial and its relationshipto the war. At the court-martialLe vy sought to defend himself by showing that his disparaging remarks about the Green Berets, identifying them as "killers of peasants and murderers of women and children," were true and that his refusal to teach medicine to Green Beret soldiers was dictated by medical ethics, given the ways in which the soldiers would misuse their medical knowledge.