Introduction to the Interviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conversion to Tibetan Buddhism: Some Reflections Bei Dawei

4 Conversion to Tibetan Buddhism: Some Reflections Bei Dawei Abstract Tibetan Buddhism, it is often said, discourages conversion. The Dalai Lama is one of many Buddhist leaders who have urged spiritual seekers not to convert to Tibetan Buddhism, but to remain with their own religions. And yet, despite such admonitions, conversions somehow occur—Tibetan dharma centers throughout the Americas, Europe, Oceania, and East/Southeast Asia are filled with people raised as Jews, Christians, or followers of the Chinese folk religion. It is appropriate to ask what these new converts have gained, or lost; and what Tibetan Buddhism and other religions might do to better adapt. One paradox that emerges is that Western liberals, who recoil before the fundamentalists of their original religions, have embraced similarly authoritarian, literalist values in foreign garb. This is not simply an issue of superficial cultural differences, or of misbehavior by a few individuals, but a systematic clash of ideals. As the experiences of Stephen Batchelor, June Campbell, and Tara Carreon illustrate, it does not seem possible for a viable “Reform” version of Tibetan Buddhism (along the lines of Reform Judaism, or Unitarian Universalism) ever to arise—such an egalitarian, democratic, critical ethos would tend to undermine the institution of Lamaism, without which Tibetan Buddhism would lose its raison d’être. The contrast with the Chinese folk religion is less obvious, since Tibetan Buddhism appeals to many of the same superstitious compulsions, and there is little direct disagreement. Perhaps the key difference is that Tibetan Buddhism (in common with certain institutionalized forms of Chinese Buddhism) expands through predation upon weaker forms of religious identity and praxis. -

The Mirror 84 January-February 2007

THE MIRROR Newspaper of the International Dzogchen Community JAN/FEB 2007 • Issue No. 84 NEW GAR IN ROMANIA MERIGAR EAST SUMMER RETREAT WITH CHÖGYAL NAMKHAI NORBU RETREAT OF ZHINE AND LHAGTHONG ACCORDING TO ATIYOGA JULY 14-22, 2007 There is a new Gar in Romania called Merigar East. The land is 4.5 hectares and 600 meters from the Black Sea. The Gar is 250 meters from a main road and 2 kilometers from the nearest village called the 23rd of August (the day of liberation in World War II); it is a 5-minute walk to the train station and a 10-minute walk to the beach. There are small, less costly hotels and pensions and five star hotels in tourist towns and small cities near by. There is access by bus, train and airplane. Inexpensive buses go up and down the coast. There is an airport in Costanza, 1/2 hour from the land, and the capital, Bucharest, 200 kilometers away, offers two international airports. At present we have only the land, but it will be developed. As of January 2007 Romania has joined the European Union. Mark your calendar! The Mirror Staff Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in the Tashigar South Gonpa on his birthday N ZEITZ TO BE IN INSTANT PRESENCE IS TO BE BEYOND TIME The Longsal Ati’i Gongpa Ngotrod In this latest retreat, which was through an intellectual analysis of CHÖGYAL NAMKHAI NORBU Retreat at Tashigar South, Argentina transmitted all around the world by these four, but from a deep under- SCHEDULE December 26, 2006 - January 1, 2007 closed video and audio webcast, standing of the real characteristics thanks to the great efforts and work of our human existence. -

Zhitro Le Cento Divinità Pacifiche E Irate, L’Essenza Del Cuore Ovvero La Pura Essenza Radiante

Zhitro Le Cento Divinità Pacifiche e Irate, l’essenza del cuore ovvero la pura essenza radiante tratto da un’insegnamento di A_zom Rinpoche Osel Thegchog Ling – San Francisco (USA) Scelto, adattato e tradotto da Raffaele Phuntsog Wangdu e Salvatore Tondrup Wangchuk ::.© 2009 Vajrayana.it .:: Zhitro Le Cento Divinità Pacifiche e Irate, l’essenza del cuore ovvero la pura essenza radiante La principale pratica della divinità di meditazione dell’Osel Thegchog Ling 1 è la sadhana di ZhiTro - le Cento Divinità Pacifiche e Irate del Bardo. Questa sadhana è sorta nella mente di Rinpoche come un terma. Si dice che il solo ascoltare la lettura ad alta voce di questa sadhana pianti i semi della liberazione, per non parlare poi di praticarla realmente. Zhitro è la pratica principale della Scuola Nyingma del Buddhismo Tibetano. Centinaia di migliaia di praticanti hanno ottenuto il corpo d’arcobaleno, principalmente attraverso questa pratica della rete magica (Guhyagarbha Tantra). Le divinità pacifiche e irate sono indicative di un’espressione dinamica sia della vacuità che della compassione. In relazione alla vacuità, le pacifiche; in relazione alla compassione, le irate. Se sei curioso di sapere quali siano le espressioni, le manifestazioni della vacuità e della compassione, bene: sono loro. I maggiori germi dell’esistenza ciclica sono il desiderio e la rabbia, e il nostro lavoro è quello di sopraffarli attraverso la meditazione. Questa è la reale essenza della pratica delle Cento Divinità; andare al di là di attaccamento e avversione. L’aspetto irato è esclusivamente una manifestazione della compassione, esso non è il furore dell’ira. Non c’è sofferenza in tutto il loro furore, il loro aspetto straordinariamente irato serve a recidere la radice dell’ira, essi non sono irati. -

The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-Pa Formations

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-09-13 The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations Emory-Moore, Christopher Emory-Moore, C. (2012). The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28396 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/191 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-pa Formations by Christopher Emory-Moore A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2012 © Christopher Emory-Moore 2012 Abstract This thesis explores the adaptation of the Tibetan Buddhist guru/disciple relation by Euro-North American communities and argues that its praxis is that of a self-motivated disciple’s devotion to a perceptibly selfless guru. Chapter one provides a reception genealogy of the Tibetan guru/disciple relation in Western scholarship, followed by historical-anthropological descriptions of its practice reception in both Tibetan and Euro-North American formations. -

15. March 2020 Retreat with Shedrup Lopon Geshe Lodoe Tsukphud

14. – 15. MARCH 2020 RETREAT WITH SHEDRUP LOPON GESHE LODOE TSUKPHUD Organizers: Maud Lennkh, Amrei Vogel Donation: 100. EUR Registration: [email protected] (to be paid in cash upon arrival) AnmendungFabienneAlexia bei: Mü[email protected] Programme Manager [email protected] Retreat Details: Schedule: The weekend seminar will focus on the preparatory 14 & 15 March 2020 10:00 18:00 practices according to the YUNGDRUNG BÖN TRADITION. (Admittance 9:30) In the spiritual tradition of Yungdrung Bön, individual practice begins with the preliminary exercises called Event Location: NGÖNDRO (sngon 'gro), according to the transmissions of ZHANG ZHUNG NYEN GYUD (zhang zhung snyan rgyud). Drikung Gompa, These practices include prayers, reflective thought Buddhistisches Zentrum processes, visualizations, movements, and internal Fleischmarkt 16, 1. Floor commitment. The preliminaries comprise GURUYOGA, 1010 Vienna, Austria IMPERMANENCE, CONFESSION OF WRONGDOING, Translation from English to German BODHICITTA, REFUGE, MANDALA OFFERING, MANTRA RECITATION, OFFERING OF ONE’S OWN BODY, INVOCATION, DEDICATION. Having become familiar with them, one can move on to DZOGCHEN (rdzogs chen), literally translated 'great perfection', as the main practice of meditation. In this seminar SHEDRUP LOPON GESHE LODOE TSUKPHUD will explain the deep meaning of the preliminary practices. He will show that the preliminary practices must not only be accomplished, but that they must be deeply understood and carried out thoroughly. They facilitate the process of taming and purifying one's own state of mind and the reflection on essential factors of human life. With this focus, the benefit for the main practice becomes clear and the participants receive an introduction to DZOGCHEN and practice it. -

Advanced Colloquial Tibetan Language Summer Intensive Orientation Sessions Start from June 9, and Classes Run from June 14 to August 5, 2021 (Eight Weeks)

Advanced Colloquial Tibetan Language Summer Intensive Orientation sessions start from June 9, and classes run from June 14 to August 5, 2021 (eight weeks) The Centre for Buddhist Studies at Rangjung Yeshe Institute is pleased to offer a summer of intensive colloquial Tibetan language training. Instructors in the program are native Tibetan speakers and international faculty from the Centre for Buddhist Studies. Classes are held Mondays through Fridays. Course Structure and Time Schedule: Advanced Colloquial Hours per week Section 1 Section 2 Tibetan, TLAN 320 (Nepal Time) (Nepal Time) Live Master Class Four one-hour M-T-W-Th M-T-W-Th classes per week 7:45a-8:45a 8:15p-9:15p Text Class (taught by Five one-hour M-T-W-Th-F Pre-recorded, available monastic professor) classes per week 9:00a-10:00a on demand Assistant Language Five one-hour Individually allocated Individually allocated Instructor (ALI) One- classes per week on-one classes Dharma Conversation Five one-hour Individually allocated Individually allocated (ALI) One-on-one classes per week classes In addition to live classes, prerecorded videos are also available for study and review prior to the live classes at a time of your own choosing. Plus: Virtual office hours to provide 1-to-1 support. Course Description: This summer intensive is offered for advanced students of colloquial Tibetan who are interested in improving both their colloquial and Dharma Tibetan fluency. The course is designed for students who have already completed four semesters, or the equivalent, of formal colloquial Tibetan study, at least one year of Classical Tibetan, and who have a familiarity with Tibetan Buddhist topics and vocabulary. -

Fall 2019 Newsletter

ALUMNI RYIReconnect ALUMNI NEWSLETTER Fall 2019 Welcome from Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche Welcome from Head of Student Services Alumni Events RYI News RYI Offer Alumni Stay Connected RANGJUNG YESHE INSTITUTE CENTRE FOR BUDDHIST STUDIES Welcome from Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche Dear Alumni, I am thinking of all of you and wondering where you are and what you are doing. Please don’t forget Rangjung Yeshe Institute! With love and blessings, Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche Welcome from Head of Student Services Dear Alumni, First of all, thanks to all of you for your ongoing support of RYI! It is wonderful to hear that many of you are presenting at, participating in, or supporting Buddhist Studies conferences and centers around the world, and it is especially touching to see how much you are doing for the world. We eagerly await having you more involved in our alumni program and in being a wonderful resource for our present students. Looking very much forward to seeing many of you at our annual alumni dinner in November, here in Boudhanath, Tina ALUMNI EVENTS: Annual Alumni Dinner RYI invites each of you to our annual alumni dinner, which is being hosted during the annual RYI Fall Seminar. This year, the dinner will be on Saturday, November 23, at 6 p.m. If you are able to join, please RSVP by November 20 to www.ryi.org/ contact-us. RYI Alumni Dinner Have you ever studied or taught at RYI? Then you (and your significant other) are invited to join RYI’s annual alumni dinner Saturday, November 23, 2019 at 6 p.m. -

The Inconceivable Lotus Land of Padma Samye Ling the Tsasum

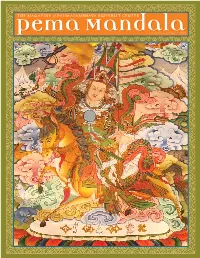

The Inconceivable Lotus Land of Padma Samye Ling The Tsasum Lingpa Wangchen Clear Garland Crystals of Fire A Brief Biography of the Great Tertön Tsasum Lingpa Magical Illusion Net: The Glorious Guhyagarbha Tantra Spring/Summer 2009 In This Issue Volume 8, Spring/Summer 2009 1 Letter from the Venerable Khenpo Rinpoches A Publication of 2 The Inconceivable Lotus Land of Padma Samye Ling Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 6 PSL Stupa Garden 7 The Tsasum Lingpa Wangchen Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche 9 A Brief Biography of the Great Tertön Tsasum Lingpa Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 11 Clear Garland Crystals of Fire Ani Lorraine , Co-Editor 13 Magical Illusion Net: The Glorious Guhyagarbha Tantra Pema Dragpa , Co-Editor Andrew Cook , Assistant Editor 16 Schedule of Teachings Pema Tsultrim , Coordinator Medicine Buddha Revitalization Retreat: Beth Gongde , Copy Editor 18 Rejuvenate the Body, Refresh the Mind Michael Ray Nott , Art Director Sandy Mueller , Production Editor 19 PBC on YouTube PBC and Pema Mandala Office 20 A Commentary on Dudjom Rinpoche’s For subscriptions or contributions Mountain Retreat Instructions to the magazine, please contact: Glorifying the Mandala Padma Samye Ling 24 Attn: Pema Mandala 25 PSL Garden 618 Buddha Highway Sidney Center, NY 13839 26 2008 Year in Review (607) 865-8068 Kindly note: This magazine contains sacred images and should not be [email protected] disposed of in the trash. It should either be burned or shredded with the remainder going into clean recycling. Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions Cover: Gesar prayer flag flying at Padma Samye Ling submitted for consideration. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „When Sūtra Meets Tantra – Sgam po pa’s Four Dharma Doctrine as an Example for his Synthesis of the Bka’ gdams- and Mahāmudrā-Systems“ Verfasser Mag. Rolf Scheuermann angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 792 389 392 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Sprachen und Kulturen Südasiens und Tibets, Fachbereich: Tibeto- logie und Buddhismuskunde Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Klaus-Dieter Mathes 3 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 9 The Subject ....................................................................................................................... 9 Outline ............................................................................................................................ 18 Methods and Aims .......................................................................................................... 24 State of Research ............................................................................................................ 27 Part I ̶ Four Dharmas of Sgam po pa ............................................................................... 31 1. Four Dharmas of Sgam po pa and its Role in Sgam po pa’s Doctrinal System ..... 33 1.1 Formulations .................................................................................................... -

PDF Download

Who? What? Where? When? Why? Uncovering the Mysteries of Monastery Objects by Ven. Shikai Zuiko o-sensei Zenga by Ven. Anzan Hoshin roshi Photographs by Ven. Shikai Zuiko o-sensei and Nathan Fushin Comeau Article 1: Guan Yin Rupa As you enter the front door of the Monastery you may have noticed a white porcelain figure nearly two feet tall standing on the shelf to the left. Who is she? Guan Yin, Gwaneum, Kanzeon, are some of the names she holds from Chinese, Korean, and Japanese roots. The object is called a "rupa" in Sanskrit, which means "form" and in this case a statue that has the form of a representation of a quality which humans hold dear: compassion. I bought this 20th century rupa shortly after we established a small temple, Zazen-ji, on Somerset West. This particular representation bears a definite resemblance to Ming dynasty presentations of "One Who Hears the Cries of the World". Guan Yin, Gwaneum, Kanzeon seems to have sprung from the Indian representation of the qualities of compassion and warmth portrayed under another name; Avalokitesvara. The name means "looking down on and hearing the sounds of lamentation". Some say that Guan Yin is the female version of Avalokitesvara. Some say that Guan Yin or, in Japan, Kannon or Kanzeon, and Avalokitesvara are the same and the differences in appearance are the visibles expression of different influences from different cultures and different Buddhist schools, and perhaps even the influence of Christianity's madonna. Extensive background information is available in books and on the web for those interested students. -

A Short Biography of Four Tibetan Lamas and Their Activities in Sikkim

BULLETIN OF TIBETOLOGY 49 A SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF FOUR TIBETAN LAMAS AND THEIR ACTIVITIES IN SIKKIM TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Summarised English translation by Saul Mullard and Tsewang Paljor Translators’ note It is hoped that this summarised translation of Lama Tsultsem’s biography will shed some light on the lives and activities of some of the Tibetan lamas who resided or continue to reside in Sikkim. This summary is not a direct translation of the original but rather an interpretation aimed at providing the student, who cannot read Tibetan, with an insight into the lives of a few inspirational lamas who dedicated themselves to various activities of the Dharma both in Sikkim and around the world. For the benefit of the reader, we have been compelled to present this work in a clear and straightforward manner; thus we have excluded many literary techniques and expressions which are commonly found in Tibetan but do not translate easily into the English language. We apologize for this and hope the reader will understand that this is not an ‘academic’ translation, but rather a ‘representation’ of the Tibetan original which is to be published at a later date. It should be noted that some of the footnotes in this piece have been added by the translators in order to clarify certain issues and aspects of the text and are not always a rendition of the footnotes in the original text 1. As this English summary will be mainly read by those who are unfamiliar with the Tibetan language, we have refrained from using transliteration systems (Wylie) for the spelling of personal names, except in translated footnotes that refer to recent works in Tibetan and in the bibliography. -

Pema Mandalamandalaspring~Summer 2015 in THIS ISSUE

THE MAGAZINE of PADMASAMBHAVA BUDDHIST CENTER PemaPema MandalaMandalaspring~summer 2015 IN THIS ISSUE 1 Letter from Venerable Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 2 Lotus Land of Glorious Wisdom 4 Be Courageous 5 All Teachings Are on Refuge 6 Pemai Chiso Dharma Store 8 Chain of Golden Mountains 10 Everything is Mind 11 Gratitude for Our Wonderful Sangha 12 The Two Truths 13 Join PBC and Support Our Nuns and Monks GREG KRANZ GREG 14 2015 Summer/Fall Teaching Schedule Warm Greetings and Best Wishes to All Sangha and Friends, 16 Revealing the Buddha Within very spring we enjoy the opportunity to look happy, meaningful times we can all look forward to as 17 A Wealth of Translations by Dharma Samudra Publications back and celebrate another beautiful year over- we continue on this path of love and peace! flowing with many wonderful Dharma activi- 17 Living at PSL ties and events! I’m so thankful for everyone’s As we all know, again and again we must examine our E motivation, and reconnect to our true nature of love, continued support of PBC and your devotion to the 18 Great Purity: The Life and Teachings of Buddhadharma, the Nyingma lineage, and the legacy compassion, and wisdom and sincerely wish the best Rongzompa Mahapandita of our precious teacher, Venerable Khenchen Palden for everyone. This is the essence of Dharma, and the Sherab Rinpoche. sole purpose for our activities. We’ve all heard this many 24 The Unfolding Beauty of Padma Samye Ling times, but it remains true. The essence of Dharma is un- This past year we consecrated Palden Sherab Pema changing—it is great love and compassion that reaches 26 2014 Year in Review Ling in Jupiter, Florida, and enjoyed many retreats at out and supports limitless beings according to exactly PSL and our other PBC Centers—including special what’s helpful.