Mise En Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

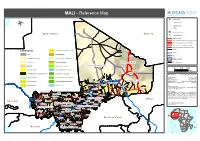

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

The Lost & Found Children of Abraham in Africa and The

SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International The Lost & Found Children of Abraham In Africa and the American Diaspora The Saga of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ & Their Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination by Abu Alfa Umar MUHAMMAD SHAREEF bin Farid 0 Copyright/2004- Muhammad Shareef SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/www,siiasi.org All rights reserved Cover design and all maps and illustrations done by Muhammad Shareef 1 SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/ www.siiasi.org ﺑِ ﺴْ ﻢِ اﻟﻠﱠﻪِ ا ﻟ ﺮﱠ ﺣْ ﻤَ ﻦِ ا ﻟ ﺮّ ﺣِ ﻴ ﻢِ وَﺻَﻠّﻰ اﻟﻠّﻪُ ﻋَﻠَﻲ ﺳَﻴﱢﺪِﻧَﺎ ﻣُ ﺤَ ﻤﱠ ﺪٍ وﻋَﻠَﻰ ﺁ ﻟِ ﻪِ وَ ﺻَ ﺤْ ﺒِ ﻪِ وَ ﺳَ ﻠﱠ ﻢَ ﺗَ ﺴْ ﻠِ ﻴ ﻤ ﺎً The Turudbe’ Fulbe’: the Lost Children of Abraham The Persistence of Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. The Origin of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 4. Social Stratification of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 5. The Turudbe’ and the Diffusion of Islam in Western Bilad’’s-Sudan 6. Uthman Dan Fuduye’ and the Persistence of Turudbe’ Historical Consciousness 7. The Asabiya (Solidarity) of the Turudbe’ and the Philosophy of History 8. The Persistence of Turudbe’ Identity Construct in the Diaspora 9. The ‘Lost and Found’ Turudbe’ Fulbe Children of Abraham: The Ordeal of Slavery and the Promise of Redemption 10. Conclusion 11. Appendix 1 The `Ida`u an-Nusuukh of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 12. Appendix 2 The Kitaab an-Nasab of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 13. -

Ken Bugul's Cendres Et Braises

"Mother and l, We are Muslim Women": Islam and Postcolonialism in Mariama Ndoye's Comme Je bon pain and Ken Bugul's Cendres et braises By Fatoumata Diahara Traoré Institute of Islamic Studies McGill University Montreal Canada August 2005 A Thesis Suhmitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts ©Fatoumata Diahara Traoré 2005 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-24927-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-24927-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell th es es le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Taoudeni Basin Report

Integrated and Sustainable Management of Shared Aquifer Systems and Basins of the Sahel Region RAF/7/011 TAOUDENI BASIN 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION EDITORIAL NOTE This is not an official publication of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The content has not undergone an official review by the IAEA. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the IAEA or its Member States. The use of particular designations of countries or territories does not imply any judgement by the IAEA as to the legal status of such countries or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or of the delimitation of their boundaries. The mention of names of specific companies or products (whether or not indicated as registered) does not imply any intention to infringe proprietary rights, nor should it be construed as an endorsement or recommendation on the part of the IAEA. INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION REPORT OF THE IAEA-SUPPORTED REGIONAL TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT RAF/7/011 TAOUDENI BASIN COUNTERPARTS: Mr Adnane Souffi MOULLA (Algeria) Mr Abdelwaheb SMATI (Algeria) Ms Ratoussian Aline KABORE KOMI (Burkina Faso) Mr Alphonse GALBANE (Burkina Faso) Mr Sidi KONE (Mali) Mr Aly THIAM (Mali) Mr Brahim Labatt HMEYADE (Mauritania) Mr Sidi Haiba BACAR (Mauritania) EXPERT: Mr Jean Denis TAUPIN (France) Reproduced by the IAEA Vienna, Austria, 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION Table of Contents 1. -

Decentralization in Mali ...54

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD2913 Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR36.1 MILLION (US$50 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF MALI FOR A DEPLOYMENT OF STATE RESOURCES FOR BETTER SERVICE DELIVERY PROJECT April 26, 2019 Governance Global Practice Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective March 31, 2019) Currency Unit = FCFA 584.45 FCFA = US$1 1.39 US$ = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Regional Vice President: Hafez M. H. Ghanem Country Director: Soukeyna Kane Senior Global Practice Director: Deborah L. Wetzel Practice Manager: Alexandre Arrobbio Task Team Leaders: Fabienne Mroczka, Christian Vang Eghoff, Tahirou Kalam SELECTED ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFD French Development Agency (Agence Française de Développement) ANICT National Local Government Investment Agency (Agence Nationale d’Investissement des Collectivités Territoriales) ADR Regional Development Agency (Agence Regionale de Developpement) ASA Advisory Services and Analytics ASACO Communal Health Association (Associations de Santé Communautaire) AWPB Annual Work Plans and Budget BVG Office of the Auditor General ((Bureau du Verificateur) CCC Communal Support -

A Peace of Timbuktu: Democratic Governance, Development And

UNIDIR/98/2 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva A Peace of Timbuktu Democratic Governance, Development and African Peacemaking by Robin-Edward Poulton and Ibrahim ag Youssouf UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1998 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/98/2 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.98.0.3 ISBN 92-9045-125-4 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research UNIDIR is an autonomous institution within the framework of the United Nations. It was established in 1980 by the General Assembly for the purpose of undertaking independent research on disarmament and related problems, particularly international security issues. The work of the Institute aims at: 1. Providing the international community with more diversified and complete data on problems relating to international security, the armaments race, and disarmament in all fields, particularly in the nuclear field, so as to facilitate progress, through negotiations, towards greater security for all States and towards the economic and social development of all peoples; 2. Promoting informed participation by all States in disarmament efforts; 3. Assisting ongoing negotiations in disarmament and continuing efforts to ensure greater international security at a progressively lower level of armaments, particularly nuclear armaments, by means of objective and factual studies and analyses; 4. -

THE POLITICS and POLICY of DECENTRALIZATION in 1990S MALI

THE POLITICS AND POLICY OF DECENTRALIZATION IN 1990s MALI Elizabeth A. Pollard Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the African Studies Program, Indiana University August 2014 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Osita Afoaku, PhD ____________________________________ Maria Grosz-Ngaté, PhD ____________________________________ Jennifer N. Brass, PhD ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page ………………………………………………………………………………………... i Acceptance Page ………………………………………………………………………………… ii Chapters Chapter 1 ………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter 2 ……………………………………………………………………………….. 19 Chapter 3 ……………………………………………………………………………….. 35 Chapter 4 ……………………………………………………………………………….. 49 Chapter 5 ……………………………………………………………………………….. 72 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 82 References ……………………………………………………………………………………… 84 Curriculum Vitae iii CHAPTER 1 Introduction A. Statement of the Problem At the end of the Cold War, the government of Mali, like governments across Africa, faced increased pressure from international donors and domestic civil society to undertake democratic reforms. In one notable policy shift, French President François Mitterrand made clear to his African counterparts at the June 1990 Franco-African summit, that while France was committed to supporting its former colonies through the economic -

Community Schools in Mali: a Multilevel Analysis Christine Capacci Carneal

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 Community Schools in Mali: A Multilevel Analysis Christine Capacci Carneal Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION COMMUNITY SCHOOLS IN MALI: A MULTILEVEL ANALYSIS By CHRISTINE CAPACCI CARNEAL A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Christine Capacci Carneal defended on April 6, 2004. ___________________________________ Karen Monkman Professor Directing Dissertation ___________________________________ Rebecca Miles Outside Committee Member ___________________________________ Peter Easton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________________ Carolyn D. Herrington, Chair, Department of Education Leadership and Policy Studies The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The idea to pursue a Ph.D. did not occur to me until I met George Papagiannis in Tallahassee in July 1995. My husband and I were in Tallahassee for a friend’s wedding and on a whim, remembering that both George and Jack Bock taught at FSU, I telephoned George to see if he had any time to meet a fan of his and Bock’s book on NFE. Anyone who knew George before he died in 2003 understands that it is hard to resist his persuasive recruiting techniques. He was welcoming, charming, and outspoken during my visit, and also introduced me to Peter Easton. After meeting both of these gentlemen, hearing about their work and the IIDE program, I felt that I finally found the right place to satisfy my learning desires. -

20100706 西非洲傳統國家(C. 750-1900S)

西非洲傳統國家 (c. 750-1900s) 蔡百銓 (作者為獨立研究者) 本文是 2010 年 5 月 5 日,在成功大學歷史系發表演講的講稿。台灣說要走進國際社會、要擴大國際視野、經貿要全球佈局,卻懶得研究別人的歷史文 化! African Kingdoms • 開場白 • 第一節 西非洲地理範疇 • 第二節 撒黑爾帝國背景:穿越撒哈拉貿易 (約從公元前 400 年開始) • 第三節 撒黑爾傳統帝國 (約從公元 750 年開始) :迦納、馬利、松蓋、班巴拉、波努 • 第四節 撒哈拉貿易衰微與傳統帝國淪亡 • 第五節 回教聖戰帝國:富塔札隆、富塔托洛、索可托哈里發國、馬西那、 土庫勒、瓦蘇祿 • 第六節 熱帶森林傳奇:阿善特、歐友、貝寧、達荷美 • 結語:拓荒者言 開場白 本文旨在激發同學對於非洲史興趣。缺乏第一手資料,不是學術論文。文中許多年代各家說法不一,無從確定。在十九與二十世紀之交歐洲人征服西非 洲之前,當地漠南非洲黑人曾經建立許多傳統帝國或王國。這些國家可以分為三大類: 1. 位在穿越撒哈拉貿易路線上的國家 2. 為了抵抗歐洲基督徒而出現的回教聖戰國家 3. 最南側幾內亞灣畔國家 約從公元前 400 年開始,主要拜駱駝與馬匹之賜,撒哈拉沙漠南緣的撒黑爾 (Sahel) 與地中海畔的北非洲之間出現「穿越撒哈拉貿易」。這帶給撒黑爾 財富,興起繁榮城市,公元八世紀更出現迦納帝國。十一世紀迦納衰微後,其他帝國相繼或同時出現。 然而「穿越撒哈拉貿易」逐漸衰微。因為十五世紀葡萄牙人直接航海前來西非洲海岸貿易,其他歐洲國家繼之。十六世紀,摩洛哥帝國興兵南下,破壞 撒哈拉貿易路線。而歐洲商人從事奴隸貿易,三個多世紀擄走西非洲許多人口,瓦解當地社會。這些貿易帝國無力抵抗歐洲帝國侵入與殖民而淪亡。 在另一方面,歐洲基督徒前來西非洲,意外激發當地伊斯蘭信仰振興,促成富拉尼族建立若干「聖戰帝國」。此外,在貝寧灣 (舊名奴隸海岸 Slave Coast) 沿岸,奴隸貿易昌盛,激勵阿善特帝國 (今迦納中部) 、達荷美王國 (今貝寧) 、歐友與貝寧帝國 (今奈及利亞西南部) 出現或茁壯。 1905 年歐友帝 國遭到英帝國兼併,西非洲最後的傳統國家消失。 第一節 西非洲地理範疇 根據聯合國「地理次區域藍圖」 (scheme for geographic subregions) ,非洲分為五個次區域。西非洲是其一,包括 16 個獨立國家與英國屬地聖赫倫 那 (Saint Helena) ,即上左圖淺綠色地帶。這 16 個國家可以分為: 前法國屬地 (9 國) : 尼日、布吉納法索 (前上伏塔) 、馬利 (前法屬蘇丹) 、 茅利塔尼亞、塞內加爾、幾內亞、象牙海岸、多哥 註 1 、 貝 寧 (前達荷美) 前英國屬地 (4 國) : 甘比亞、迦納 (前黃金海岸) 、獅子山、奈及利亞 前葡萄牙屬地 (2 國) : 幾內亞比索、維德角 (在大西洋) 原為獨立國家 (1 國) : 賴比瑞亞 (1848- ) 撒哈拉沙漠 (公元前 3000 年-) 非洲大陸從地中海往南看,可以辨認數個生態區域 (ecoregions) : 1. 北非洲地中海沿岸 2. 撒哈拉沙漠,隔離北非洲與漠南非洲 3. 撒哈拉南部邊緣的撒黑爾 (Sahel) ,一條帶狀、狹窄的半乾旱熱帶稀 樹草原。南側是熱帶多樹大草原 (tropical savanna) ,最南方是幾 內亞灣畔熱帶雨林。 撒哈拉沙漠西起大西洋沿岸,東抵紅海,北界阿特拉斯山脈 (Atlas Mts.) 和地 音 ﺤﺻ ﺮ ا ء 中海,南達蘇丹和尼日河河谷 (Niger Valley) 。「撒哈拉」是阿拉伯語 譯,源自阿拉伯文與當地游牧民族圖阿雷格族 (Tuaregs) -

IMRAP, Interpeace. Self-Portrait of Mali on the Obstacles to Peace. March 2015

SELF-PORTRAIT OF MALI Malian Institute of Action Research for Peace Tel : +223 20 22 18 48 [email protected] www.imrap-mali.org SELF-PORTRAIT OF MALI on the Obstacles to Peace Regional Office for West Africa Tel : +225 22 42 33 41 [email protected] www.interpeace.org on the Obstacles to Peace United Nations In partnership with United Nations Thanks to the financial support of: ISBN 978 9966 1666 7 8 March 2015 As well as the institutional support of: March 2015 9 789966 166678 Self-Portrait of Mali on the Obstacles to Peace IMRAP 2 A Self-Portrait of Mali on the Obstacles to Peace Institute of Action Research for Peace (IMRAP) Badalabougou Est Av. de l’OUA, rue 27, porte 357 Tel : +223 20 22 18 48 Email : [email protected] Website : www.imrap-mali.org The contents of this report do not reflect the official opinion of the donors. The responsibility and the respective points of view lie exclusively with the persons consulted and the authors. Cover photo : A young adult expressing his point of view during a heterogeneous focus group in Gao town in June 2014. Back cover : From top to bottom: (i) Focus group in the Ségou region, in January 2014, (ii) Focus group of women at the Mberra refugee camp in Mauritania in September 2014, (iii) Individual interview in Sikasso region in March 2014. ISBN: 9 789 9661 6667 8 Copyright: © IMRAP and Interpeace 2015. All rights reserved. Published in March 2015 This document is a translation of the report L’Autoportrait du Mali sur les obstacles à la paix, originally written in French.