IMRAP, Interpeace. Self-Portrait of Mali on the Obstacles to Peace. March 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rp-Ebandiagara.Pdf (5.189Mb)

TENURE AND TREE MANAGEMENT ON THE DOGON PLATEAU THREE CASE STUDIES IN BANDIAGARA, MALI by Rebecca J. McLain All views,. interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions ex- pressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations. Land Tenure Center University of Wisconsin-Madison March 1990 CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Section I. First Trimester Work Objectives 3 A. Project Personnel 3 B. Office Facilities and Equipment 4 C. Initial Contacts 4 D. Document Review 4 E. Conferences and Meetings 5 F. CARE Forestry Activities 7 G. Selection of the Land Tenure Study Sites 10 Section II. Pilot Study Results: Arrondissement Central de Bandiagara 13 A. Selection of Study Sites 13 B. Methodology 13 C. Geographical Setting 16 D. Economic Activities 17 E. Land Tenure System in the Central Arrondissement of Bandiagara 20 F. Tree Use, Tree Tenure, and Tree Management 25 G. The Villager's View of the Forest Code 39 H. Implications of the Research Findings for VRP Activities 41 I. Future Activities 43 iii LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES Page Figure 1 Fifth Region Study Sites 11 Figure 2 Research Study Areas: Arrondissement Central de Bandiagara 14 Table 1 Field Tenure Categories in Three Dogon Villages: Songho, Doukombo, and Kalibombo 21 Table 2 Some Uses of Trees in the Arrondissement Centrale of Bandiagara 26 Table 3 Trees Planted by Case-Study Farmers 36 Table 4 Trees Protected by Case-Study Farmers 37 Table 5 Soil Conservation and Improvement Techniques Used by Case-Study Farmers 38 TENURE AND TREE MANAGEMENT ON THE DOGON PLATEAU : THREE CASE STUDIES IN BANDIAGARA, MALI by Rebecca J. -

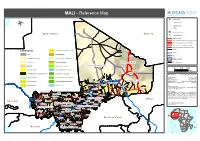

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

Modele De Monogaphie : Cercle De Yelimane

REGION DE KAYES RÉPUBLIQUE DU MALI CONSEIL DE CERCLE DE YELIMANE UN PEUPLE - UN BUT - UNE FOI COMMUNE RURALE DE GORY PROJET D’APPUI A LA GOUVERNANCE DU DEVELOPPEMENT ET A LA GESTION DES RESSOURCES NATURELLES DU CERCLE DE YELIMANE MONOGRAPHIE DE LA COMMUNE RURALE DE GORY COLLECTIF INGENIEURS DEVELOPPEMENT SAHEL Siège social : B.P. 309 - Kayes Tél/fax : 00223 21 52 21 78/ 66 95 12 33 / 66 74 50 07 e.mail : [email protected] / [email protected] Version provisoire Septembre 2009 1 SOMMAIRE MISE EN SITUATION .......................................................................................................................................... 5 I- LE CONTEXTE............................................................................................................. 6 II- LES OBJECTIFS ....................................................................................................... 7 III- L’EQUIPE ET LA DEMARCHE METHODOLOGIQUE .................................. 7 IV- LES DIFFICULTES ET LIMITES ........................................................................ 8 4-1 LES DIFFICULTES ....................................................................................................................... 8 4-2 LES LIMITES DE L’ETUDE : .......................................................................................................... 9 PREMIERE PARTIE : HISTORIQUE ET CARACTERISTIQUES PHYSIQUES ............................................... 10 I- HISTORIQUE........................................................................................................... -

African Rivers Developpement Smartrivers2019

papers_Afri9 SMART RIVERS 2019 Special Session African Rivers developpement Title Country Auteur Company Faisabilit3 de la navigabilit3 sur le Fleuve Niger, Bief Ayourou Gaya Belgium Andr3 Hage DNWT Am3lioration de l2accFs du port de Bra77aville par la navigation France Francis FR.CHART Consultant Design of the navigation channel on the Senegal River Belgium S3bastien PAGE IMDC A new paradigm for river management: Application to the Niger Inner Delta in Mali Belgium 6ean Michel HIVER .LB Spatial altimetry to improve inland navigation in the Congo basin France Sebastien LEGRAND CNR D3veloppement dLun outil dLaide E la navigation sur le bassin du Congo issu dLun Systme dLInformations hydrologiques nouvelle g3n3ration France Damien BR.NEL BRL Page 6 Smart Rivers 2019 Conference / September 30 - October 3, 2019 Cité Internationale / Centre de Congrès Lyon FRANCE / Réf. auteur: Arnaud DE BONVILLER – ISL Ingénierie 25 rue Lenepveu - 49100 Angers France [email protected] Co-auteurs: André HAGE – DN&T Rue de la Belle Jardinière 256, 4031 Liège Belgique [email protected] Seidou SODIA – Ministère de l’équipement (Niger) [email protected] Mots clés: Fleuve africain, navigabilité, cadre juridique, logistique fluviale, exploitation durable, infrastructure Faisabilité de la navigabilité sur le Fleuve Niger, Bief Ayourou-Gaya. Article court Introduction En 2016, le Ministère de l’Equipement Niger a confié à ISL Ingénierie et DN&T l’étude de faisabilité de la navigation sur le Fleuve Niger. La République du Niger est traversée dans sa partie occidentale sur 550 km par le fleuve, principale source en eau de surface qui porte le même nom que le pays. -

340102-Fre.Pdf (433.2Kb)

r 1 RAPPORT DE MISSION [-a mission que nous venons de terminer avait pour but de mener une enquête dans quelques localités du Mali pour avoir une idée sur la vente éventuelle de I'ivermectine au Mali et le suivi de la distribution du médicament par les acteurs sur le terrain. En effet sur ordre de mission No 26/OCPlZone Ouest du3l/01196 avec le véhicule NU 61 40874 nous avons debuté un périple dans les régions de Koulikoro, Ségou et Sikasso et le district de Bamako, en vue de vérifier la vente de l'ivermectine dans les pharmacies, les dépôts de médicament ou avec les marchands ambulants de médicaments. Durant notre périple, nous avons visité : 3 Régions : Koulikoro, Ségou, Sikasso 1 District : Bamako 17 Cercles Koulikoro (06 Cercles), Ségou (05 Cercles), Sikasso (06 Cercles). 1. Koulikoro l. Baraouli 1. Koutiala 2. Kati 2. Ségou 2. Sikasso 3. Kolokani 3. Macina 3. Kadiolo 4. Banamba 4. Niono 4. Bougouni 5. Kangaba 5. Bla 5. Yanfolila 6. Dioila 6. Kolondiéba avec environ Il4 pharmacies et dépôts de médicaments, sans compter les marchands ambulants se trouvant à travers les 40 marchés que nous avons eu à visiter (voir détails en annexe). Malgré notre fouille, nous n'avons pas trouvé un seul comprimé de mectizan en vente ni dans les pharmacies, ni dans les dépôts de produits pharmaceutiques ni avec les marchands ambulants qui ne connaissent d'ailleurs pas le produit. Dans les centres de santé où nous avons cherché à acheter, on nous a fait savoir que ce médicament n'est jamais vendu et qu'il se donne gratuitement à la population. -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

Colonial Legacies and Preservice Teacher

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library COLONIAL LEGACIES AND PRESERVICE TEACHER SUBJECTIVITIES IN MALI: A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF TWO TEACHER TRAINING PROGRAMS by Talatou Abdoulaye A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Education, Culture and Society The University of Utah August 2017 Copyright © Talatou Abdoulaye 2017 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Talatou Abdoulaye has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Dolores Calderon , Chair 03/08/2017 Date Approved Donna Deyhle , Member Date Approved James Lehning , Member 03/09/2017 Date Approved Frank Margonis , Member 03/09/2017 Date Approved Veronica Valdez , Member 03/09/2017 Date Approved and by William Smith , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Education, Culture and Society and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT The main goal of this dissertation is to identify major characteristics of French colonial education in Soudan Francais (present day Mali) before discussing ways in which, despite major education reforms, legacies that relate to those characteristics continue to, either consciously or unconsciously, be reproduced, altered, or challenged in two current higher education teacher-training programs in postcolonial Mali. The discussions offer insights with regard to how issues of reproduction, hybridity, and resistance play out in various data sources before examining ways in which they affect the subjectivities of preservice teachers graduating from the two teacher training programs investigated. -

Land Rights U N D E R N E G O T I a T I

BULLETIN OF THE DRYLANDS: PEOPLE, POLICIES, PROGRAMMES No. 39, May 2001 Land rights un d e r ne g o t i a t i o n pages 12-15 IN THIS ISSUE No. 39 May 2001 Ed i t o r i a l NEWS 3 Impact of climate change on drylands • More or HE presidents of South Africa, Nigeria and Algeria less poverty? • Rio + 10 • Trade or aid? T have been drawing up a new MAP for Africa. The Millennium Africa Programme (or MAP for short) INTERVIEW 6 commits African governments to respect human rights Haramata meets Mr Amara Diaby, mayor and the rule of law. President Mbeki who has been of Gogui commune, Mali spearheading the initiative argues that African leaders RESEARCH AGENDAS 8 must take responsibility for providing a more favourable Land rights under pressure • Farms and economic and political environment to encourage livelihoods transformed • Learning lessons sustainable growth and tackle poverty. Investors, both from the South domestic and foreign, need a firm demonstration that government will play by the rules. Rather than wait for FEATURE 12 the World Bank and IMF to lay down conditions, African Derived rights: Gaining access to land leaders should press their fellow presidents to abide by in West Africa these commitments. Such interference in neighbours’ affairs runs counter to the Organisation of African Unity LAND MATTERS 16 (OAU) charter but the principle of non-interference has Water: the key to pastoral resource management • Landnet West Africa meets • recently been broken in practice on many occasions. Evaluating Eden The OAU which meets in July to agree the MAP’s ISSUES AND PROGRAMMES 19 objectives and design offers a valuable chance to push Land titles: do they matter? governments towards greater accountability to their peoples. -

Stamps from Mali Were of Relatively Large Size and Compared to Surface Mail Stamps Their Topics Were Directed More Towards International Events and Organizations

African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 30; Jan Jansen Mali, April 2018 African Studies Centre Leiden African Postal Heritage APH Paper 30 Jan Jansen Stamp Emissions as a Sociological and Cultural Force – The Case of Mali Introduction Postage stamps and related objects are miniature communication tools, and they tell a story about cultural and political identities and about artistic forms of identity expressions. They are part of the world’s material heritage, and part of history. Ever more of this postal heritage becomes available online, published by stamp collectors’ organizations, auction houses, commercial stamp shops, online catalogues, and individual collectors. Virtually collecting postage stamps and postal history has recently become a possibility. These working papers about Africa are examples of what can be done. But they are work-in-progress! Everyone who would like to contribute, by sending corrections, additions, and new area studies can do so by sending an email message to the APH editors: Ton Dietz ([email protected]) and/or Jan Jansen ([email protected]). You are welcome! Disclaimer: illustrations and some texts are copied from internet sources that are publicly available. All sources have been mentioned. If there are claims about the copy rights of these sources, please send an email to [email protected], and, if requested, those illustrations will be removed from the next version of the working paper concerned. 1 African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

1 NIGER WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Reporting Date: From

NIGER WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Reporting date: From 20thJuly to 26th August 2012 I. Overview At least 44 people have been killed and thousands more made homeless after heavy floods caused the Niger River to overflow earlier this week, flooding parts of the capital Niamey and other areas. Up to 340,000 people have been affected by the floods, Niger's government has said. It has declared a state of emergency and called for urgent international aid for 2,000 displaced people. The first foreign aid plane chartered by Ireland and bringing tents, mosquito nets and ther relief items to victims of Niger's flood in Dosso area, arrived Sunday in Niamey. UNHCR has agreed to contribute to the inter-agency humanitarian response and has in that respect released 900 of the 2000 Plastic sheeting it plans to make available. UNHCR participated in a UN agencies joint evaluation mission in the Tillabery area aimed at identifying special assistance needs for the disaster stricken population following the recent floodings In total, 172 new households of 961 individuals have been registered in the three camps during the studied week. Arrivals are now slow but steady. II - Major Developments The general situation remains calm in the country. During the week under report, the frequent rains have caused floods throughout Niger. As a consequence access to the camps are made even more difficult. In terms of damage caused to physical infrastructure the camps have been relatively spared except for Tabareybayrey. The heavy wind and the rains from the 18th and 19th have destroyed several of the MSF tents building which serves as medical center,with serious damages to medical equipments and medical supply. -

Arrêt N° 01/10/CCT/ME Du 23 Novembre 2010

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du vingt trois novembre deux mil dix tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-031 du 27 mai 2010 portant code électoral et ses textes modificatifs subséquents ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2010-668/PCSRD du 1er octobre 2010 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le référendum sur la Constitution de la VIIème République ; Vu la requête en date du 8 novembre 2010 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) et les pièces jointes ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 003/PCCT du 8 novembre 2010 de Madame le Président du Conseil Constitutionnel portant désignation d’un Conseiller-Rapporteur ; Ensemble les pièces jointes ; Après audition du Conseiller – rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME Considérant que par lettre n° 190/P/CENI en date du 8 novembre 2010, le Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) a saisi le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition aux fins de valider