THE POLITICS and POLICY of DECENTRALIZATION in 1990S MALI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JPC.CCP Bureau Du Prdsident

Onchoccrciasis Control Programmc in the Volta Rivcr Basin arca Programme de Lutte contre I'Onchocercose dans la R6gion du Bassin de la Volta JOIN'T PROCRAMME COMMITTEE COMITE CONJOINT DU PROCRAMME Officc of the Chuirrrran JPC.CCP Bureau du Prdsident JOINT PROGRAII"IE COMMITTEE JPC3.6 Third session ORIGINAL: ENGLISH L Bamako 7-10 December 1982 October 1982 Provisional Agenda item 8 The document entitled t'Proposals for a Western Extension of the Prograncne in Mali, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ssnegal and Sierra Leone" was reviewed by the Corrrittee of Sponsoring Agencies (CSA) and is now transmitted for the consideration of the Joint Prograurne Conrnittee (JPC) at its third sessior:. The CSA recalls that the JPC, at its second session, following its review of the Feasibility Study of the Senegal River Basin area entitled "Senegambia Project : Onchocerciasis Control in Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, l,la1i, Senegal and Sierra Leone", had asked the Prograrrne to prepare a Plan of Operations for implementing activities in this area. It notes that the Expert Advisory Conrnittee (EAC) recormnended an alternative strategy, emphasizing the need to focus, in the first instance, on those areas where onchocerciasis was hyperendemic and on those rivers which were sources of reinvasion of the present OCP area (Document JPC3.3). The CSA endorses the need for onchocerciasis control in the Western extension area. However, following informal consultations, and bearing in mind the prevailing financial situation, the CSA reconrnends that activities be implemented in the area on a scale that can be managed by the Prograrmne and at a pace concomitant with the availability of funds, in order to obtain the basic data which have been identified as missing by the proposed plan of operations. -

Mali Overview Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Africa MRG Directory –> Mali –> Mali Overview Print Page Close Window Mali Overview Environment Peoples History Governance Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment The Republic of Mali is a landlocked state in West Africa that extends into the Sahara Desert in the north, where its north-eastern border with Algeria begins. A long border with Mauritania extends from the north, then juts west to Senegal. In the west, Mali borders Senegal and Guinea; to the south, Côte d'Ivoire; to the south-east Burkina Faso, and in the east, Niger. The country straddles the Sahara and Sahel, home primarily to nomadic herders, and the less-arid south, predominately populated by farming peoples. The Niger River arches through southern and central Mali, where it feeds sizeable lakes. The Senegal river is an important resource in the west. Mali has mineral resources, notably gold and phosphorous. Peoples Main languages: French (official), Bambara, Fulfulde (Peulh), Songhai, Tamasheq. Main religions: Islam (90%), traditional religions (6%), Christian (4%). Main minority groups: Peulh (also called Fula or Fulani) 1.4 million (11%), Senoufo and Minianka 1.2 million (9.6%), Soninké (Saracolé) 875,000 (7%), Songhai 875,000 (7%), Tuareg and Maure 625,000 (5%), Dogon 550,000 (4.4%) Bozo 350,000 (2.8%), Diawara 125,000 (1%), Xaasongaxango (Khassonke) 120,000 (1%). [Note: The percentages for Peulh, Soninke, Manding (mentioned below), Songhai, and Tuareg and Maure, as well as those for religion in Mali, come from the U.S. State Department background note on Mali, 2007; Data for Senoufo and Minianka groups comes from Ethnologue - some from 2000 and some from 1991; for Dogon from Ethnologue, 1998; for Diawara and Xaasonggaxango from Ethnologue 1991; Percentages are converted to numbers and vice-versa using the State Department's 2007 estimated total population of 12.5 million.] Around half of Mali's population consists of Manding (or Mandé) peoples, including the Bambara (Bamana) and the Malinké. -

World Bank Document

69972 Options for Preparing a Sustainable Land Management (SLM) Program in Mali Consistent with TerrAfrica for World Bank Engagement at the Country Level Introduction Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Background and rationale: 1. One of the most environmentally vulnerable areas of the world is the drylands of sub-Saharan Africa, particularly the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and Southeast Africa. Mali, as with other dryland areas in this category, suffers from droughts approximately every 30 years. These droughts triple the number of people exposed to severe water scarcity at least once in every generation, leading to major food and health crisis. In general, dryland populations lag far behind the rest of the world in human well-being and development indicators. Similarly, the average infant mortality rate for dryland developing countries exceeds that for non-dryland countries by 23% or more. The human causes of degradation1 and desertification2 include direct factors such as land use (agricultural expansion in marginal areas, deforestation, overgrazing) and indirect factors (policy failures, population pressure, land tenure). The biophysical impacts of dessertification are regional and global climate change, impairment of carbon sequestation capacity, dust storms, siltation into rivers, downstream flooding, erosion gullies and dune formation. The social impacts are devestating- increasing poverty, decreased agricultural and silvicultural production and sometimes Public Disclosure Authorized malnutrition and/or death. 2. There are clear links between land degradation and poverty. Poverty is both a cause and an effect of land degradation. Poverty drives populations to exploit their environment unsustainably because of limited resources, poorly defined property rights and limited access to credit, which prevents them from investing resources into environmental management. -

Between Islamization and Secession: the Contest for Northern Mali

JULY 2012 . VOL 5 . ISSUE 7 Contents Between Islamization and FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Between Islamization and Secession: Secession: The Contest for The Contest for Northern Mali By Derek Henry Flood Northern Mali REPORTS By Derek Henry Flood 6 A Profile of AQAP’s Upper Echelon By Gregory D. Johnsen 9 Taliban Recruiting and Fundraising in Karachi By Zia Ur Rehman 12 A Biography of Rashid Rauf: Al-Qa`ida’s British Operative By Raffaello Pantucci 16 Mexican DTO Influence Extends Deep into United States By Sylvia Longmire 19 Information Wars: Assessing the Social Media Battlefield in Syria By Chris Zambelis 22 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 24 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts An Islamist fighter from the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa in the city of Gao on July 16, 2012. - AFP/Getty Images n january 17, 2012, a rebellion 22, disgruntled Malian soldiers upset began in Mali when ethnic about their lack of support staged a coup Tuareg fighters attacked a d’état, overthrowing the democratically Malian army garrison in the elected government of President Amadou Oeastern town of Menaka near the border Toumani Touré. with Niger.1 In the conflict’s early weeks, the ethno-nationalist rebels of the By April 1, all Malian security forces had National Movement for the Liberation evacuated the three northern regions of of Azawad (MNLA)2 cooperated and Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu. They relocated About the CTC Sentinel sometimes collaborated with Islamist to the garrisons of Sévaré, Ségou, and The Combating Terrorism Center is an fighters of Ansar Eddine for as long as as far south as Bamako.4 In response, independent educational and research the divergent movements had a common Ansar Eddine began to aggressively institution based in the Department of Social enemy in the Malian state.3 On March assert itself and allow jihadists from Sciences at the United States Military Academy, regional Islamist organizations to West Point. -

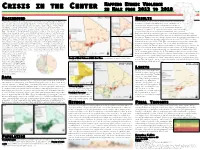

Mapping Ethnic Violence in Mali From

RISIS IN THE ENTER MAPPING ETHNIC VIOLENCE C C IN MALI FROM 2012 TO 2018 BACKGROUND RESULTS This project’s purpose is to analyze where ethnic violence is taking place in Mali since The population maps showed a higher density of people and set- the Tuareg insurgency in January 2012. Chaos from the insurgency created a power tlement in the South, with minimal activity in the North; this is vacuum in the North, facilitating growing control by Islamic militants (“Africa: Mali — consistent with relevant research and presents the divide be- The World Factbook” 2019). While a French-led operation reclaimed the North in tween the two, fueled by imbalances in government resources. 2013, Islamic militant groups have gained control of rural areas in the Center (“Africa: The age of this data (2013) is a potential source of error. The spatial Mali — The World Factbook” 2019). These groups exploited and encouraged ethnic analysis shows that ethnic violence is concentrated in the center of rivalries in Central Mali, stirring up intercommunal violence. Mali’s central and north- Mali, particularly Mopti and along that area of the Burkina Faso border. Conflict ern regions have faced lacking government resources and management, creating events near the border in Burkina Faso were not recorded, but could have aided in grievances between ethnic groups that rely on clashing livelihoods. Two of the key the analysis. There are two clear changes demonstrated by mapping kernel density of ethnic groups forming militias and using violence are the Dogon and Fulani. The vio- individual incidents from the beginning of the Malian crisis (2012-2015) and those lence between these groups is exacerbated by some of the Islamic militant groups from more recent years (2016-2018). -

Under the Gun Resource Conflicts and Embattled Traditional Authorities in Central Mali

Under the gun Resource conflicts and embattled traditional authorities in Central Mali CRU Report Anca-Elena Ursu Under the gun Resource conflicts and embattled traditional authorities in Central Mali Anca-Elena Ursu CRU Report July 2018 July 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Anca-Elena Ursu, April, 2018 Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the author Anca-Elena Ursu is a research assistant with Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit. A legal professional by training, she works at the intersection of traditional justice and local governance in the Sahel. The Clingendael Institute P.O. -

A Peace of Timbuktu: Democratic Governance, Development And

UNIDIR/98/2 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva A Peace of Timbuktu Democratic Governance, Development and African Peacemaking by Robin-Edward Poulton and Ibrahim ag Youssouf UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1998 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/98/2 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.98.0.3 ISBN 92-9045-125-4 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research UNIDIR is an autonomous institution within the framework of the United Nations. It was established in 1980 by the General Assembly for the purpose of undertaking independent research on disarmament and related problems, particularly international security issues. The work of the Institute aims at: 1. Providing the international community with more diversified and complete data on problems relating to international security, the armaments race, and disarmament in all fields, particularly in the nuclear field, so as to facilitate progress, through negotiations, towards greater security for all States and towards the economic and social development of all peoples; 2. Promoting informed participation by all States in disarmament efforts; 3. Assisting ongoing negotiations in disarmament and continuing efforts to ensure greater international security at a progressively lower level of armaments, particularly nuclear armaments, by means of objective and factual studies and analyses; 4. -

Country Profiles

1 2017 ANNUAL2018 REPORT:ANNUAL UNFPA-UNICEF REPORT GLOBAL PROGRAMME TO ACCELERATE ACTION TO END CHILD MARRIAGE COUNTRY PROFILES UNFPA-UNICEF GLOBAL PROGRAMME TO ACCELERATE ACTION TO END CHILD MARRIAGE The Global Programme to Accelerate Action to End Child Marriage is generously funded by the Governments of Belgium, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom and the European Union and Zonta International. Front cover: © UNICEF/UNI107875/Pirozzi © United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) August 2019 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH COUNTRYCOUNTRY PROFILE PROFILE © UNICEF/UNI179225/LYNCH BANGLADESH COUNTRY PROFILE 3 2 RANGPUR 1 1 2 2 1 3 2 1 1 Percentage of young women SYLHET (aged 20–24) married or in RAJSHAHI 59 union by age 18 DHAKA 2 2 Percentage of young women 1 KHULNA (aged 20–24) married or in CHITTAGONG 22 union by age 15 Percentage of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in BARISAL union before 1 age 18 3 2 0-9% 2 10-19% 20-29% 30-39% 40-49% 50-59% UNFPA + UNICEF implementation 60-69% 70-79% UNFPA implementation 80<% UNICEF implementation 1 Implementation outcome 1 (life skills and education support for girls) 2 Implementation outcome 2 (community dialogue) 3 3 Implementation outcome 3 (strengthening education, 2.05 BIRTHS PER WOMAN health and child protection systems) Total fertility rate (average number of children a woman would have by Note: This map is stylized and not to scale. It does not reflect a position by the end of her reproductive period if her experience followed the currently UNFPA or UNICEF on the legal status of any country or area or the delimitation of any frontiers. -

Community Schools in Mali: a Multilevel Analysis Christine Capacci Carneal

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 Community Schools in Mali: A Multilevel Analysis Christine Capacci Carneal Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION COMMUNITY SCHOOLS IN MALI: A MULTILEVEL ANALYSIS By CHRISTINE CAPACCI CARNEAL A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Christine Capacci Carneal defended on April 6, 2004. ___________________________________ Karen Monkman Professor Directing Dissertation ___________________________________ Rebecca Miles Outside Committee Member ___________________________________ Peter Easton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________________ Carolyn D. Herrington, Chair, Department of Education Leadership and Policy Studies The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The idea to pursue a Ph.D. did not occur to me until I met George Papagiannis in Tallahassee in July 1995. My husband and I were in Tallahassee for a friend’s wedding and on a whim, remembering that both George and Jack Bock taught at FSU, I telephoned George to see if he had any time to meet a fan of his and Bock’s book on NFE. Anyone who knew George before he died in 2003 understands that it is hard to resist his persuasive recruiting techniques. He was welcoming, charming, and outspoken during my visit, and also introduced me to Peter Easton. After meeting both of these gentlemen, hearing about their work and the IIDE program, I felt that I finally found the right place to satisfy my learning desires. -

Assessing Cropland Abandonment in Mopti Region with Satellite Imagery

December 2019 MALI Assessing cropland abandonment in Mopti region with satellite imagery Since 2018, Mopti region has been marred by an escalation in violence. In the eastern part of the region, intercommunal tensions have Key points increasingly taken on the character of a conflict between armed groups, • Insecurity peaks in 2019 including ethnically based militias and self-defence groups. Rising levels heavily affected agricultural of violence have threatened food security, with a loss of livelihoods for activities in the eastern part displaced populations, difficulties in cultivating fields and accessing of Mopti region markets for those who have remained in their villages. • In total, 25% of villages in Given the vast area of Mopti region, the consequences of the conflict on the region are affected by a decrease in cropland areas the landscape are difficult to consistently monitor. Moreover, the access in 2019, compared to pre- to many communes has been heavily restricted due to the present conflict years (2016, 2017) circumstances. Consequently, little to no field data could be collected in 2019 for some parts of the region. Satellite imagery helped to assess the • The most affected areas are Koro, Bankass and impact of violent events on agricultural land in the region. Bandiagara cercles, as well as the commune of Mondoro In October 2019, the Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping unit (VAM) of the World Food Programme conducted a geospatial analysis, measuring the • Evidence visible from space degree of change in cultivated areas between 2019 and years prior to translate into situations of the degradation of the security situation, covering Mopti region. -

Senegambian Confederation: Prospect for Unity on the African Continent

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 7 Number 1 Volume 7, Number 1, Summer 1986 Article 3 1986 SENEGAMBIAN CONFEDERATION: PROSPECT FOR UNITY ON THE AFRICAN CONTINENT Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation (1986) "SENEGAMBIAN CONFEDERATION: PROSPECT FOR UNITY ON THE AFRICAN CONTINENT," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol7/iss1/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NOTE SENEGAMBIAN CONFEDERATION: PROSPECT FOR UNITY ON THE AFRICAN CONTINENT* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................ 46 II. THE SHADOW OF CONFEDERATION .......................... 47 A. Debate on the Merits of a Union: 1960-81 ......... 47 B. Midwife to Confederation: 1981 Coup Attempt in The G ambia ... .. ............................ 56 III. THE SUBSTANCE OF CONFEDERATION ........................ 61 A. Introduction to the Foundation Document and Pro- to co ls . 6 1 B. Defense of The Confederation and Security of Mem- ber S ta tes ...................................... 65 C. Foreign Policy of the Confederation and Member S tates . .. 6 9 D. Unity of Member Nations' Economies and Confed- eral F inance .................................... 71 1. Econom ic Union ............................. 71 2. Confederal Finance .......................... 76 E. Confederal Institutions and Dispute Resolution ... 78 1. Institutions ................................. 78 2. Dispute Resolution ........................... 81 IV. REACTION TO THE CONFEDERATION ................... 82 V. FUTURE PROSPECTS: CONFEDERATION LEADING TO FEDERA- TIO N ? . .. .. 8 4 V I. -

Observing the 2002 Mali Presidential Elections: Final Report

Observing the 2002 Mali Presidential Elections Observing the 2002 Mali Presidential Elections Final Report Final Report The Carter Center The Carter Center 453 Freedom Parkway 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta. GA 30307 Atlanta. GA 30307 (404) 420-5100 (404) 420-5100 fax (404) 420-5196 fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org www.cartercenter.org October 2002 October 2002 Table of Contents Table of Contents Mali Presidential Elections Delegation p. 3 Mali Presidential Elections Delegation p. 3 Executive Summary p. 4 Executive Summary p. 4 Background p. 7 Background p. 7 Election Preparations p. 9 Election Preparations p. 9 January 2002: Carter Center Exploratory Assessment p. 15 January 2002: Carter Center Exploratory Assessment p. 15 April-May 2002: Carter Center Observer Mission p. 17 April-May 2002: Carter Center Observer Mission p. 17 Conclusions and Recommendations p. 30 Conclusions and Recommendations p. 30 Postscript: Mali’s 2002 Legislative Elections p. 35 Postscript: Mali’s 2002 Legislative Elections p. 35 Acknowledgments p. 37 Acknowledgments p. 37 Appendices p. 38 Appendices p. 38 About The Carter Center p. 42 About The Carter Center p. 42 2 2 Mali Presidential Elections Delegation Mali Presidential Elections Delegation Delegation Leader Delegation Leader David Pottie, Senior Program Associate, The Carter Center, Canada David Pottie, Senior Program Associate, The Carter Center, Canada Delegation Members Delegation Members Annabel Azim, Program Assistant, The Carter Center, Morocco Annabel Azim, Program Assistant, The Carter Center,