And Violations of This Right in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johnson Gbende Faleyimu-Master Thesis

UNESCO CHAIR OF PHILOSOPHY FOR PEACE UNIVERSITAT JAUME I MILITARY INTERVENTION IN NIGERIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM: ITS IMPACT ON DEMOCRATIC DEVELOPMENT (1993-1999) MASTER THESIS Student: Johnson Gbende Faleyimu Supervisor: Dr Jose Angel Ruiz Jimenez Tutor: Dr Irene Comins Mingol Castellón, July 2014 Abstract Key words: Military, intervention, democracy and Nigerian politics A study of literature on civil-military relations in Nigeria reveals a question: why does the military intervene in the politics of some countries but remain under firm civilian control in others? This thesis delves into military intervention in Nigerian Politics and its general impact on democracy (1993-1999). The military exploits its unique and pivotal position by demanding greater institutional autonomy and involvement when the civilian leadership fails. The main purpose of this study is to discourage military intervention in Nigeria politics, and to encourage them to focus their primary assignment of lethal force, which includes use of weapons, in defending its country by combating actual or perceived threats against the state. i Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my late parents High Chief J.F Olijogun and Olori Meminat Marian Olijogun ii Acknowledgements My sincere gratitude goes to God and all who contributed to the successful completion of this thesis work. Very special thanks to my supervisor, Dr Jose Angel Ruiz Jimenez of University of Granada, for his brilliant guidance and encouragement-what a wonderful display of wealth of experience-without which this thesis would not have been possible. My profound appreciation goes to the lecturers and staffs of the International Master’s Degree Program in Peace, Conflict and Development studies at the Universitat Jaume I, who gave me all the skills and knowledge that are required to carry out an academic research and other academic endeavours. -

Nigeria Apr2001

NIGERIA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT APRIL 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 2. GEOGRAPHY 2.1 3. ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.3 4. HISTORY Post - independence historical background The Abacha Regime 4.1 - 4.2 4.3 - 4.8 Death of Abacha and related events up until December 1998 4.9 - 4.16 Investigations into corruption 4.17 - 4.21 Local elections - 5 December 1998 4.22 Governorship and House of Assembly Elections 4.23 - 4.24 4.25 - 4.26 Parliamentary elections- 20/2/99 4.27 Presidential elections - 27/2/99 4.28 - 4.29 Recent events 5. HUMAN RIGHTS: INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE POLITICAL SYSTEM 5.1 - 52 THE CONSTITUTION 5.3 - 5.5 THE JUDICIARY 5.6 - 5.8 (i) Past practise 5.9 - 5.13 (ii) Present position 5.14 - 5.15 5.16 - 5.19 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.20 - 5.22 THE SECURITY SERVICES 5.23 - 5.26 POLICE 5.27 - 5.30 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.31 - 5.35 HEALTH AND SOCIAL WELFARE 6. HUMAN RIGHTS: ACTUAL PRACTICE WITH REGARD TO HUMAN RIGHTS (i) The Abacha Era (ii) The Abubakar Era 6.1 - 62 6.3 - 66 (iii) Current Human Rights Situation 6.7 1 7. HUMAN RIGHTS: GENERAL ASSESSMENT SECURITY SITUATION FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY/OPINION: 7.1 - 7.3 (i) The situation under Abacha: 7.4 (ii) The situation under General Abubakar 7.5 - 7.8 (iii) The present situation 7.9 - 7.14 MEDIA FREEDOM (i) The situation under Abacha: 7.15 (ii) The situation under General Abubakar 7.16 (iii) The situation under the present government 7.17 - 7.26 7.28 - 7.30 Television and Radio FREEDOM OF RELIGION 7.31 - 7.36 (i) The introduction of Sharia law, and subsequent events. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

S/No Placement 1

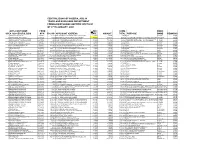

S/NO PLACEMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - OTA, OGUN 1 STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, SANGO, 2 AGEGE, LAGOS STATE 3 AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE CLOSE, 7 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, IBADAN, 8 OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, 9 ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU ODE ROAD, 10 IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN STREET, 11 AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. VICTORIA ISLAND, 12 LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, OPP. 13 TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AHMAN 14 PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, OLD JEBBA 15 ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE ROAD, 16 AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE FEDERAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY, MURTALA MOHAMMED AIRPORT, IKEJA, 18 LAGOS STATE FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH OSHODI (FIIRO), 3, FIIRO 19 ROAD, OFF CAPPA BUS STOP, AGEGE MOTOR ROAD, OSHODI, LAGOS FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE & RURAL DEVELOPMENT, FOOD & STRATEGIC GRAINS RESERVE DEPARTMENT (FRSD) SILO COMPLEX, KWANA 20 WAYA, YOLA, ADAMAWA STATE 21 FRESH COUNTRY CHICKEN ENTERPRISES, SHONGA, KWARA STATE 22 GOLDEN PENNY FLOUR MILLLS, APAPA WHARF, APAPA, LAGOS STATE HURLAG TECHNOLOGIES, 7, LADIPO OLUWOLE STREET, OFF ADENIYI JONES 23 AVENUE, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 24 IBN DEND, FARM, KM. -

Odo/Ota Local Government Secretariat, Sango - Agric

S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 1 OTA, OGUN STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 2 SANGO, AGEGE, LAGOS STATE AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 3 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 7 CLOSE, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 8 IBADAN, OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 9 OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 10 ODE ROAD, IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 11 STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 12 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING OPP. TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 13 DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 14 AHMAN PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 15 OLD JEBBA ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE Page 1 SIWES PLACEMENT COMPANIES & ADDRESSES.xlsx S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 16 ROAD, AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. -

Foreign Exchange Auction No.7/2003 of 27Th January, 2003 Applicant Name Form Bid Cumm

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA, ABUJA TRADE AND EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO.7/2003 OF 27TH JANUARY, 2003 APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMM. BANK S/N A. SUCCESSFUL BIDS M'/'A' R/C NO APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT TOTAL PURPOSE NAME REMARKS 1 JOHNLEONARD AGBAWA AA0887779 A112120 BLOCK 15,SHOPS 9-10,PROMISE LAND,LADIPO,LAGOS 129.0000 2,000.00 2,000.00 PTA PRUDENT 0.0036 2 BIZLAND INVESTMENT CO.LTD. MF0334519 346509 BLOCK D,SHOP 3,OLANIYONU MKT.ORILE IGANMU 128.5000 20,327.60 22,327.60 FIRE FIGHTING EQUIPMENT FOR SAVING LIFE & PROPERTYFIRST BANK 0.0364 3 HOESCH PIPE MILLS (NIGERIA) LIMITED MF0052008 13688 KM 38, LAGOS-ABEOKUTA ROAD, SANGO - OTA. 128.1000 28,336.07 50,663.67 MACHINERY & EQUIPMENT FOR THE MANUFACTURE CITIBANK 0.0506 4 HOESCH PIPE MILLS (NIGERIA) LIMITED MF0119783 13688 KM 38, LAGOS-ABEOKUTA ROAD, SANGO - OTA. 128.1000 7,476.00 58,139.67 INDUSTRIALOF CEILING TILES. RAW MATERIAL 42 MT OF FIBROUS CITIBANK 0.0133 5 AJE OLUFUMILAYO AJIBOLA AA887677 A1723761 13,TOYIN STREET,IKEJ,LAGOS 128.0000 1,000.00 59,139.67 PTABLASTER YAPITEK. PRUDENT 0.0018 6 IBIMIDUN ADETOKUNBO OLUSESAN AA0747953 C544303 7, BROWN STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS 128.0000 2,000.00 61,139.67 PTA ACCESS 0.0036 7 MAN KENIZ INTERNATIONAL LTD AA0887176 RC360010 LINE M NO 24 ARIARA INTERNATIONAL MARKET,ONITHSA,ANAMBRA128.0000 2,500.00 63,639.67 BTA PRUDENT 0.0045 8 O.M.CHARLESONS LTD MF0368631 82696 30,VENN ROAD SOUTH ONITSHA, ONITSHA. 128.0000 24,061.08 87,700.75 PHOTOGRAPHIC CHEMICALS ACCESS 0.0429 9 OFORMA ERNEST AA0887175 A0772661 NO 3 U-LINE ARIARIA INTERNATIONAL -

The Making of Sani Abacha There

To the memory of Bashorun M.K.O Abiola (August 24, 1937 to July 7, 1998); and the numerous other Nigerians who died in the hands of the military authorities during the struggle to enthrone democracy in Nigeria. ‘The cause endures, the HOPE still lives, the dream shall never die…’ onderful: It is amazing how Nigerians hardly learn frWom history, how the history of our politics is that of oppor - tunism, and violations of the people’s sovereignty. After the exit of British colonialism, a new set of local imperi - alists in military uniform and civilian garb assumed power and have consistently proven to be worse than those they suc - ceeded. These new vetoists are not driven by any love of coun - try, but rather by the love of self, and the preservation of the narrow interests of the power-class that they represent. They do not see leadership as an opportunity to serve, but as an av - enue to loot the public treasury; they do not see politics as a platform for development, but as something to be captured by any means possible. One after the other, these hunters of fortune in public life have ended up as victims of their own ambitions; they are either eliminated by other forces also seeking power, or they run into a dead-end. In the face of this leadership deficit, it is the people of Nigeria that have suffered; it is society itself that pays the price for the imposition of deranged values on the public space; much ten - sion is created, the country is polarized, growth is truncated. -

Coups: the Victims, the Survivors

COUPS THE VICTIMS THE SURVIVORS Page 1 of 12 COUPS: THE VICTIMS, THE SURVIVORS THE mere mention of coup d’etat, the unconstitutional and violent overthrow of incumbent governments, sends down shivers and evokes traumatic memories from any country’s nationals. It recreates those anguished images that overwhelmed the populace when the finger pulled the trigger. Every citizen is haunted by mortal fear of the day’s uncertainty and discusses it in hushed tones, cautious that nobody eavesdrops. The penalty for participation is maximum: death. It, therefore, makes it a condemnable high risk venture. But some initiators still damn the consequences. It is all because it possesses limitless attractions and guarantees inexhaustible opportunities. Its charm is almost irresistible. Those who get hooked hardly would divorce their other collaborators. They, somewhat, lose every sense of reason and would muster whatever resources to actualise such a dream. When successful, they become instant heroes. Conversely, they are society’s villains once the plot is aborted by superior strategies or gun-power of the man in the saddle. Curiously, the coupists seek escape routes. Once arrested, investigated and convicted, they begin the final journey to the firing range or long periods of incarceration. Suddenly, the world invokes sympathy from all quarters to avoid blood-letting. Coups have their prizes and the other prices. Usually, in every attempt, there are victims and the survivors. Afterall, human beings in authority are the targets. The mission is almost always to eliminate the regime’s henchmen and take over power or to simply shove them aside without wasting lives. -

Nigeria Country Assessment

NIGERIA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT COUNTRY INFORMATION AND POLICY UNIT, ASYLUM AND APPEALS POLICY DIRECTORATE IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE VERSION APRIL 2000 I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a 6-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum producing countries in the United Kingdom. 1.5 The assessment has been placed on the Internet (http:www.homeoffice.gov.uk/ind/cipu1.htm). An electronic copy of the assessment has been made available to: Amnesty International UK Immigration Advisory Service Immigration Appellate Authority Immigration Law Practitioners' Association Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants JUSTICE 1 Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture Refugee Council Refugee Legal Centre UN High Commissioner for Refugees CONTENTS I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II. GEOGRAPHY 2.1 III. ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.3 IV. -

The Waste Management System in Low Income Areas of Jos, Nigeria: the Challenges and Waste Reduction Opportunities

THE WASTE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM IN LOW INCOME AREAS OF JOS, NIGERIA: THE CHALLENGES AND WASTE REDUCTION OPPORTUNITIES JANET AGATI YAKUBU A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2017 ABSTRACT An estimated 2 billion people do not have access to waste collection services, and 3 billion do not have access to controlled waste disposal. This lack of services and infrastructure has a detrimental impact on public health and the environment with waste being dumped or burnt in communities. With waste levels projected to double in Less Economically Developed Countries (LEDCs) by 2025 there are significant challenges facing municipalities who already lack the basic resources needed to manage waste. The United Nations acknowledged the problems of poor sanitation and waste management in the Sustainable Development Goals which sets targets to address these challenges, including the target by 2030 to substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, reuse and recycling. Jos, the capital of Plateau state in Nigeria, shares the waste management challenges facing cities in LEDCs. The population of Jos is projected to increase from 1.3 million in 2007 to 2.7 million in 2025, with much of the population living in densely populated areas that lack basic sanitation and controlled disposal of waste. This thesis presents the results of a detailed investigation into the current waste management system in Jos with a focus on low income areas. Through the adoption of mixed methods the thesis identifies how waste is currently being managed and establishes the challenges to sustainable waste management. -

Xtrawins Winners

Xtrawins Winners Transact and Win Amount CUSTOMER NAME BRANCH 2000 ANDREW EBOH 468-SEME, SEME BORDER 2000 AYODELE AYONITEMI 529-ILORIN, UMARU AUDI ROAD 2000 UMAR BASHIR 414-GARKI ABUJA MUHAMMED BUHARI WAY 2000 IDRIS OLAWALE RAHEEM 151-IKORODU 2 BRANCH 369-DEI-DEI ABUJA,BUILDING MATERIALS 2000 NNABUIKE AMAKA C MARKET 2000 MUDASHIR NUHU 362-KANO,MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY 2000 IDI NUHU 165-DAMATURU BRANCH 2000 IMANCHE ILE 423-JOS,CLUB ROAD 418-NYANYA ABUJA,OPP.NYANYA SHOPPING 2000 MARY P IFERE COMPLEX 2000 BRYAN C NWACHUKWU 442-OWERRI,DOUGLAS RD. 2000 CHIEDOZIE EZEKIEL ANI 372-ENUGU,GARDEN AVENUE 2000 AROLOYE ADEBOLA OLATOYESE 365-APAPA WHARF RD. 2000 MUHAMMED TASIU NAZIFI 604-KETU MINI 2000 UDOKA JOHN UGWU 375-LAGOS ISLAND, BALOGUN STR. 2000 VERONICA O ONYEJEGBU 394-BBA LAGOS,ATIKU ABUBAKAR PLAZA 2000 NKIRU FIDELIA NWOSISI 427-BBA LAGOS,BANK PLAZA 2000 MISHARK OGOCHUKWU ORJI 453-ORLU,ORLU INTERNATIONA MKT. 2000 IDOWU WASIU GANIYU 156-TEJUOSHO BRANCH 2000 ADEBAMBO SAHEED ADEDEJI 101-IDI-ARABA BRANCH 2000 PAUL OMOEFE EMESIRI 324-OGIDI BRANCH 2000 OGHENERUONA TED ONAYOMAKE 569-WARRI MINI 2000 ADEBAYO ADESHOLA AKINKUNMI 559-OGBOMOSHO, ILORIN ROAD 2000 DUROJAIYE MICHAEL APATAJESU 026-CALABAR BRANCH 2000 HANNAH OLUWADAMILOLA BROWNE 359-ISOLO, ASA-AFARIOGUN STR,AJAO ESTATE 2000 ADIBE MAXWELL EKENE 416-PH,50 IKWERRE ROAD 2000 OLAMILEKAN JOEL LAWAL 208-ORILE COKER 2000 KOSISOCHUKWU VIVIAN CHIMA 387-NNEWI,EDO-EZEMEWI STR. 2000 ASOGWA BLESSING CHEKWUBE 033-MAKURDI BRANCH 2000 EMUOBOSA INEDI 558-UGHELLI, MARKET ROAD 2000 JAMIU AYINDE ADEWUSI 054-IWO ROAD IBADAN BRANCH 2000 KEKERE JOSHUA 038-ADO-EKITI 2000 ISMAHIL MATTHEW YEKINNI 440-IKORODU 83 LAGOS ROAD OLAMILEKAN LATEEF LATEEF 2000 BABATUNDE 175-BODIJA BRANCH 2 2000 KABIRU MUSA MUSTY 578-UNIV. -

Ethno-Religious Conflicts, Mass Media and National Development: the Northern Nigeria Experience

i ETHNO-RELIGIOUS CONFLICTS, MASS MEDIA AND NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT: THE NORTHERN NIGERIA EXPERIENCE RAPHAEL NOAH SULE BA, MSc, MA, (JOS) UJ/2012/PGAR/0294 A thesis in the Department of RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY, Faculty of Arts, Submitted to the School of Postgraduate Studies, University of Jos, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in SOCIOLOGY OF RELIGION of the UNIVERSITY OF JOS JULY 2015 ii DECLARATION I hereby declare that this work is the product of my own research efforts; undertaken under the supervision of Professor Cyril O. Imo and has not been presented elsewhere for the award of a degree or certificate. All sources have been duly distinguished and appropriately acknowledged. --------------------------------- ------------------ RAPHAEL NOAH SULE DATE UJ/2012/PGAR/0294 iii CERTIFICATION This is to certify that the research work for this thesis and the subsequent preparation of this thesis by Raphael Noah Sule (UJ/2012/PGAR/0294) were carried out under my supervision. -------------------------------------------- Date----------------------- PROFESSOR CYRIL O. IMO SUPERVISOR ------------------------------------------- Date------------------------ PROFESSOR PAULINE MARK LERE HEAD OF DEPARTMENT ------------------------------------------- Date------------------------- PROFESSOR TOR J. IORAPUU DEAN, FACULTY OF ARTS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study would not have been possible without the contributions of other people. The role of my Supervisor Prof. C. O. Imo in painstakingly going through my write-ups at the various stages, offering corrections and suggestions that have brought it this far cannot be overemphasized. I thank him for making such contributions. Special thanks equally go to all the members of staff in the Department of Religion and Philosophy, University of Jos.