Johnson Gbende Faleyimu-Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria Apr2001

NIGERIA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT APRIL 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 2. GEOGRAPHY 2.1 3. ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.3 4. HISTORY Post - independence historical background The Abacha Regime 4.1 - 4.2 4.3 - 4.8 Death of Abacha and related events up until December 1998 4.9 - 4.16 Investigations into corruption 4.17 - 4.21 Local elections - 5 December 1998 4.22 Governorship and House of Assembly Elections 4.23 - 4.24 4.25 - 4.26 Parliamentary elections- 20/2/99 4.27 Presidential elections - 27/2/99 4.28 - 4.29 Recent events 5. HUMAN RIGHTS: INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE POLITICAL SYSTEM 5.1 - 52 THE CONSTITUTION 5.3 - 5.5 THE JUDICIARY 5.6 - 5.8 (i) Past practise 5.9 - 5.13 (ii) Present position 5.14 - 5.15 5.16 - 5.19 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.20 - 5.22 THE SECURITY SERVICES 5.23 - 5.26 POLICE 5.27 - 5.30 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.31 - 5.35 HEALTH AND SOCIAL WELFARE 6. HUMAN RIGHTS: ACTUAL PRACTICE WITH REGARD TO HUMAN RIGHTS (i) The Abacha Era (ii) The Abubakar Era 6.1 - 62 6.3 - 66 (iii) Current Human Rights Situation 6.7 1 7. HUMAN RIGHTS: GENERAL ASSESSMENT SECURITY SITUATION FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY/OPINION: 7.1 - 7.3 (i) The situation under Abacha: 7.4 (ii) The situation under General Abubakar 7.5 - 7.8 (iii) The present situation 7.9 - 7.14 MEDIA FREEDOM (i) The situation under Abacha: 7.15 (ii) The situation under General Abubakar 7.16 (iii) The situation under the present government 7.17 - 7.26 7.28 - 7.30 Television and Radio FREEDOM OF RELIGION 7.31 - 7.36 (i) The introduction of Sharia law, and subsequent events. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

Download (3763Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/145151 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications APPENDIX A Containing Violence to What End? The Political Economy of Amnesty in Nigeria’s Oil-Rich Niger Delta (2009-2016) by Elvis Nana Kwasi Amoateng A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics and International Studies University of Warwick, Department of Politics and International Studies February 2020 Contents Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures ............................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................ 7 Abstract ......................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction: ............................................................................................................... -

And Violations of This Right in Nigeria

Reference: Nigeria's initial report submitted to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights under articles 16 and 17 of the Covenant (E/1990/5/Add.31) The right to adequate food (Art. 11) and violations of this right in Nigeria Parallel report to the initial report of Nigeria concerning Economic, Social and Cultural Rights enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Submitted at the occasion of the 18th session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (27 April - 17 May, 1998) by FIAN International, an NGO in consultative status with ECOSOC, working for the Human Right to Feed Oneself, in collaboration with Shelter Rights Initiative, the Nigerian NGO for Economic Rights. Parallel information to the initial report of Nigeria concerning the right to adequate food as enshrined in the the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Preface I. Introduction A) Economy B) Population C) Geography D) The right to an adequate standard of living E) The right to trade unionism F) Education G) Health II. Documentation on violations of the right to adequate food A) The Ajaokuta steel complex B) Forcible evictions of city dwellers C) The Shiroro dam project D) The activities of oil companies and the case of the Ogoni E) The Right to work under just and favourable conditions III. Possible questions to the government of Nigeria FIAN International Secretariat Heidelberg, Germany, April 1998 Parallel information concerning the right to adequate food in Nigeria 3 Preface FIAN, the International Human Rights Organization for the Right to Feed Oneself, would like to present a parallel report to the periodic report on Nigeria submitted by the Nigerian Government. -

S/No Placement 1

S/NO PLACEMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - OTA, OGUN 1 STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, SANGO, 2 AGEGE, LAGOS STATE 3 AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE CLOSE, 7 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, IBADAN, 8 OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, 9 ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU ODE ROAD, 10 IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN STREET, 11 AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. VICTORIA ISLAND, 12 LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, OPP. 13 TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AHMAN 14 PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, OLD JEBBA 15 ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE ROAD, 16 AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE FEDERAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY, MURTALA MOHAMMED AIRPORT, IKEJA, 18 LAGOS STATE FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH OSHODI (FIIRO), 3, FIIRO 19 ROAD, OFF CAPPA BUS STOP, AGEGE MOTOR ROAD, OSHODI, LAGOS FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE & RURAL DEVELOPMENT, FOOD & STRATEGIC GRAINS RESERVE DEPARTMENT (FRSD) SILO COMPLEX, KWANA 20 WAYA, YOLA, ADAMAWA STATE 21 FRESH COUNTRY CHICKEN ENTERPRISES, SHONGA, KWARA STATE 22 GOLDEN PENNY FLOUR MILLLS, APAPA WHARF, APAPA, LAGOS STATE HURLAG TECHNOLOGIES, 7, LADIPO OLUWOLE STREET, OFF ADENIYI JONES 23 AVENUE, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 24 IBN DEND, FARM, KM. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Gowon, Babangida and Abacha Regimes

University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES by SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULTY OF HUMAN SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA January 2001 University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The financial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. My deepest gratitude to: Mr. J.T. Bekker for his guidance; Dr. Funmi Olonisakin for her advice, Estrellita Weyers for her numerous searches for sources; and last but not least, my wife Estia-Marié, for her constant motivation, support and patience. This dissertation is dedicated to the children of Africa, including my firstborn, Marco Hoogenraad-Vermaak. ii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S “General Abacha wasn’t the first of his kind, nor will he be last, until someone can answer the question of why Africa allows such men to emerge again and again and again”. BBC News 1998. Passing of a dictator leads to new hope. 1 Jul 98. iii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S SUMMARY THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES By SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK LEADER: Mr. J.T. BEKKER DEPARTMENT: POLITICAL SCIENCE DEGREE FOR WHICH DISSERTATION IS MAGISTER ARTIUM PRESENTED: POLITICAL SCIENCE) The recent election victory of gen. -

Foreign Policy and Afrocentricism: an Appraisal of Nigeria’S Role

Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies Vol. 5, No 1, June 2019 Volume and Issues Obtainable at Center for Sustainability Research and Consultancy Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies ISSN: 2519-089X (E): 2519-0326 Volume 5: No. 1, June 2019 Journal homepage: www.publishing.globalcsrc.org/jbsee Foreign Policy and Afrocentricism: An Appraisal of Nigeria’s Role 1 Muritala Dauda , 2 Mohammad Zaki Bin Ahmad , 3 Mohammad Faisol Keling 1 Ph.D Candidate, School of International Studies, College of Law, Government and International Studies (COLGIS), Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM). The Corresponding email address: [email protected]. 2 Senior Lecturer, School of International Studies, College of Law, Government and International Studies (COLGIS), Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM). ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT History Nigerian foreign policy is a tool use by the country to achieve its national Revised format: May 2019 interest. The country‘s external policy has been tailored to be Afrocentric Available Online: June 2019 since its independence in 1960 which shows the commitment of Nigeria towards Africa‘s stability and development. The principles of Nigeria‘s Keywords foreign policy and its Afrocentricism has consistently operated by the Foreign Policy, Afrocentrism, government of the country irrespective of whether it is civilian or military National Interest, Diplomacy, administration. The notion of four concentric circle of Nigerian foreign Stability policy where the country considers its national interest and the interest of its neighbouring States first, the West African sub-region, Africa‘s interest JEL Classification: and the interest of the world, have accrued numerous benefits to the L50, L52,L59, C62 country. -

Odo/Ota Local Government Secretariat, Sango - Agric

S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 1 OTA, OGUN STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 2 SANGO, AGEGE, LAGOS STATE AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 3 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 7 CLOSE, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 8 IBADAN, OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 9 OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 10 ODE ROAD, IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 11 STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 12 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING OPP. TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 13 DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 14 AHMAN PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 15 OLD JEBBA ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE Page 1 SIWES PLACEMENT COMPANIES & ADDRESSES.xlsx S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 16 ROAD, AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. -

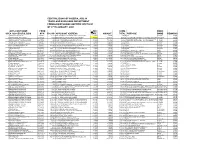

Foreign Exchange Auction No.7/2003 of 27Th January, 2003 Applicant Name Form Bid Cumm

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA, ABUJA TRADE AND EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO.7/2003 OF 27TH JANUARY, 2003 APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMM. BANK S/N A. SUCCESSFUL BIDS M'/'A' R/C NO APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT TOTAL PURPOSE NAME REMARKS 1 JOHNLEONARD AGBAWA AA0887779 A112120 BLOCK 15,SHOPS 9-10,PROMISE LAND,LADIPO,LAGOS 129.0000 2,000.00 2,000.00 PTA PRUDENT 0.0036 2 BIZLAND INVESTMENT CO.LTD. MF0334519 346509 BLOCK D,SHOP 3,OLANIYONU MKT.ORILE IGANMU 128.5000 20,327.60 22,327.60 FIRE FIGHTING EQUIPMENT FOR SAVING LIFE & PROPERTYFIRST BANK 0.0364 3 HOESCH PIPE MILLS (NIGERIA) LIMITED MF0052008 13688 KM 38, LAGOS-ABEOKUTA ROAD, SANGO - OTA. 128.1000 28,336.07 50,663.67 MACHINERY & EQUIPMENT FOR THE MANUFACTURE CITIBANK 0.0506 4 HOESCH PIPE MILLS (NIGERIA) LIMITED MF0119783 13688 KM 38, LAGOS-ABEOKUTA ROAD, SANGO - OTA. 128.1000 7,476.00 58,139.67 INDUSTRIALOF CEILING TILES. RAW MATERIAL 42 MT OF FIBROUS CITIBANK 0.0133 5 AJE OLUFUMILAYO AJIBOLA AA887677 A1723761 13,TOYIN STREET,IKEJ,LAGOS 128.0000 1,000.00 59,139.67 PTABLASTER YAPITEK. PRUDENT 0.0018 6 IBIMIDUN ADETOKUNBO OLUSESAN AA0747953 C544303 7, BROWN STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS 128.0000 2,000.00 61,139.67 PTA ACCESS 0.0036 7 MAN KENIZ INTERNATIONAL LTD AA0887176 RC360010 LINE M NO 24 ARIARA INTERNATIONAL MARKET,ONITHSA,ANAMBRA128.0000 2,500.00 63,639.67 BTA PRUDENT 0.0045 8 O.M.CHARLESONS LTD MF0368631 82696 30,VENN ROAD SOUTH ONITSHA, ONITSHA. 128.0000 24,061.08 87,700.75 PHOTOGRAPHIC CHEMICALS ACCESS 0.0429 9 OFORMA ERNEST AA0887175 A0772661 NO 3 U-LINE ARIARIA INTERNATIONAL -

The Making of Sani Abacha There

To the memory of Bashorun M.K.O Abiola (August 24, 1937 to July 7, 1998); and the numerous other Nigerians who died in the hands of the military authorities during the struggle to enthrone democracy in Nigeria. ‘The cause endures, the HOPE still lives, the dream shall never die…’ onderful: It is amazing how Nigerians hardly learn frWom history, how the history of our politics is that of oppor - tunism, and violations of the people’s sovereignty. After the exit of British colonialism, a new set of local imperi - alists in military uniform and civilian garb assumed power and have consistently proven to be worse than those they suc - ceeded. These new vetoists are not driven by any love of coun - try, but rather by the love of self, and the preservation of the narrow interests of the power-class that they represent. They do not see leadership as an opportunity to serve, but as an av - enue to loot the public treasury; they do not see politics as a platform for development, but as something to be captured by any means possible. One after the other, these hunters of fortune in public life have ended up as victims of their own ambitions; they are either eliminated by other forces also seeking power, or they run into a dead-end. In the face of this leadership deficit, it is the people of Nigeria that have suffered; it is society itself that pays the price for the imposition of deranged values on the public space; much ten - sion is created, the country is polarized, growth is truncated. -

Coups: the Victims, the Survivors

COUPS THE VICTIMS THE SURVIVORS Page 1 of 12 COUPS: THE VICTIMS, THE SURVIVORS THE mere mention of coup d’etat, the unconstitutional and violent overthrow of incumbent governments, sends down shivers and evokes traumatic memories from any country’s nationals. It recreates those anguished images that overwhelmed the populace when the finger pulled the trigger. Every citizen is haunted by mortal fear of the day’s uncertainty and discusses it in hushed tones, cautious that nobody eavesdrops. The penalty for participation is maximum: death. It, therefore, makes it a condemnable high risk venture. But some initiators still damn the consequences. It is all because it possesses limitless attractions and guarantees inexhaustible opportunities. Its charm is almost irresistible. Those who get hooked hardly would divorce their other collaborators. They, somewhat, lose every sense of reason and would muster whatever resources to actualise such a dream. When successful, they become instant heroes. Conversely, they are society’s villains once the plot is aborted by superior strategies or gun-power of the man in the saddle. Curiously, the coupists seek escape routes. Once arrested, investigated and convicted, they begin the final journey to the firing range or long periods of incarceration. Suddenly, the world invokes sympathy from all quarters to avoid blood-letting. Coups have their prizes and the other prices. Usually, in every attempt, there are victims and the survivors. Afterall, human beings in authority are the targets. The mission is almost always to eliminate the regime’s henchmen and take over power or to simply shove them aside without wasting lives. -

First Term E-Learning Note Subject: Government Class

FIRST TERM E-LEARNING NOTE SUBJECT: GOVERNMENT CLASS: SS3 SCHEME OF WORK WEEK TITLE 1. Military Rule In Nigeria: Historical Background, Reasons for Military Rule, Achievements of Military Rule in Nigeria 2. Weakness of Military Rule in Nigeria; Measures That Could be Taken to Prevent Military Intervention in Nigeria 3. Local Administration in Nigeria; Structure, Functions, Sources of Finance and Problems of Local Government: Features of 1976 Local Government Reforms in Nigeria; Roles of Traditional Rulers in Government 4. Nigeria and the World; (i) Interdependence of Nations (ii) Nigeria’s Foreign Policy; Meaning, Nigeria Foreign Policy since Independence 5. Nigeria and the World; Factors that can affect Nigeria’s Foreign Policy, Formulation of Nigeria Foreign Policy; Features of Nigeria’s Foreign Policy 6. Africa as the Center Piece of Nigeria’s Foreign Policy; Origin; Reasons for the Adoption of Nigeria as the Center Piece of Nigeria’s Foreign Policy 7. How Nigeria has Demonstrated that Africa is the Center Piece of Her Foreign Policy; Ways by which Nigeria maintains Friendly Relations with African States 8. Non-Alignment; Origin, Meaning, Aims and Objectives 9. Non-Alignment Problems; Factors that Stimulated the Formation of Non-Align Movement; Nigeria and Non-Aligned Movement 10. International Organization- Organization of African Unity (O.A.U.); Historical Perspective, Aims and Objectives, Principles 11. Organization of African Unity- Organs and functions, Aims and Objectives, Achievements and Problems 12. Revision/ Examination REFERENCE Essential Government by C.C. Dibie Comprehensive Government by J.U. Anyaele WEEK ONE MILITARY RULE IN NIGERIA HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The first military regime in Nigeria started in January 15th 1966, which was staged by five (5) Majors led by Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu.