Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: the Growth of Consciousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Required Reading January 2021 Baumanrarebooks.Com 1-800-97-Bauman (1-800-972-2862) Or 212-751-0011 [email protected]

Required Reading January 2021 BaumanRareBooks.com 1-800-97-bauman (1-800-972-2862) or 212-751-0011 [email protected] New York 535 Madison Avenue (Between 54th & 55th Streets) New York, NY 10022 800-972-2862 or 212-751-0011 Mon-Fri: 10am to 5pm and by appointment Las Vegas Grand Canal Shoppes The Venetian | The Palazzo 3327 Las Vegas Blvd., South, Suite 2856 Las Vegas, NV 89109 888-982-2862 or 702-948-1617 Mon-Sat: 11am to 7pm; Sun: 12pm to 6pm Philadelphia 1608 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 215-546-6466 | (fax) 215-546-9064 by appointment all booKS aRE ShippEd on appRoval and aRE fully guaRantEEd. Any items may be returned within ten days for any reason (please notify us before returning). All reimbursements are limited to original purchase price. We accept all major credit cards. Shipping and insurance charges are additional. Packages will be shipped by UPS or Federal Express unless another carrier is requested. Next-day or second-day air service is available upon request. www.baumanrarebooks.com twitter.com/baumanrarebooks facebook.com/baumanrarebooks On the cover: Item no. 23. On this page: Item no. 25. “The Mother Of The English 19th-Century Novel” 1. AUSTEN, Jane. The Novels. London and New York, 1896-98. Five volumes. Octavo, contemporary three- quarter tan calf gilt. $4800. Click for more info “It is a truth universally Turn-of-the-century set of Austen novels illustrated with splendid line drawings by Hugh Thomson, beautifully acknowledged that a single man bound by Henry Young and Sons of Liverpool. -

John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba

LIKE RABBITS Welcome to TimesPeople TimesPeople Lets You Share and Discover the Bes Get Started HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Books WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYL ART & DESIGN BOOKS Sunday Book Review Best Sellers First Chapters DANCE MOVIES MUSIC John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba By CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT Sig Published: January 28, 2009 wee SIGN IN TO den RECOMMEND John Updike, the kaleidoscopically gifted writer whose quartet of Cha Rabbit novels highlighted a body of fiction, verse, essays and criticism COMMENTS so vast, protean and lyrical as to place him in the first rank of E-MAIL Ads by Go American authors, died on Tuesday in Danvers, Mass. He was 76 and SEND TO PHONE Emmetsb Commerci lived in Beverly Farms, Mass. PRINT www.Emme REPRINTS U.S. Trus For A New SHARE Us Directly USTrust.Ba Lanco Hi 3BHK, 4BH Living! www.lancoh MOST POPUL E-MAILED 1 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. All rights reserved. 7/9/2009 10:55 PM LIKE RABBITS 1. Month Dignit 2. Well: 3. GLOB 4. IPhon 5. Maure 6. State o One B 7. Gail C 8. A Run Meani 9. Happy 10. Books W. Earl Snyder Natur John Updike in the early 1960s, in a photograph from his publisher for the release of “Pigeon Feathers.” More Go to Comp Photos » Multimedia John Updike Dies at 76 A star ALSO IN BU The dark Who is th ADVERTISEM John Updike: A Life in Letters Related An Appraisal: A Relentless Updike Mapped America’s Mysteries (January 28, 2009) 2 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. -

A Comparative Study of Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF GUSTAVE FLAUBERT'S MADAME BOVARY AND EMILE ZOLA'S THERESE-RAQUIN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY ALSYLVIA SMITH DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH ATLANTA, GEORGIA JUNE 1969 w TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF MADAME BOVARY 27 III. A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THERESE-RAQUIN 56 CONCLUSION 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY 86 ii PREFACE The purpose of this study is to analyze Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovarv and Emile Zola's Therese-Raquin and to point out the similari ties and differences between the two works. In order to make a com parison between these two works, a critical analysis will be made of each work, placing emphasis on the theme, style, and character develop ment. Although Madame Bovarv is a Realistic novel while TheVese-Requin is a Naturalistic novel, there still remains a great deal of similarity between the two literary works. Since Flaubert was the leader of the Realist school and Zola was the leader of the Naturalist school, it was felt that a comparative study of a representative work of each au thor would contribute to a better appreciation of these two phases of the nineteenth century novel. This study is divided into three chapters. The first chapter serves as an introduction and includes a biographical sketch of each author and vital details concerning their milieu. Chapter two consists of an analysis of Madame Bovarv. In Chapter three will be presented an analysis of Therese-Raquin. -

Madame Bovary : Notes Cliffs Notes On--; Title: Rev

Madame Bovary : Notes Cliffs Notes On--; title: Rev. Ed. author: Roberts, James Lamar. publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (US) isbn10 | asin: print isbn13: 9780822007807 ebook isbn13: 9780822071259 language: English Flaubert, Gustave,--1821-1880.--Madame subject Bovary. publication date: 1964 lcc: ddc: 840.9 Flaubert, Gustave,--1821-1880.--Madame subject: Bovary. Page i Page 1 Madame Bovary Notes by James L. Roberts, Ph.D. Department of English University of Nebraska including Introduction to the Novel Brief Synopsis of the Novel List of Characters Chapter Summaries and Commentaries Character Analyses Flaubert's Life and Works Questions for Review INCORPORATED LINCOLN. NEBRASKA 68501 Page 2 Editor Gary Carey, M.A. University of Colorado Consulting Editor James L. Roberts, Ph.D. Department of English University of Nebraska ISBN 0-8220-0780-0 © Copyright 1964 by Cliffs Notes, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed in U.S.A. 1999 Printing The Cliffs Notes logo, the names ''Cliffs" and "Cliffs Notes," and the black and yellow diagonal-stripe cover design are all registered trademarks belonging to Cliffs Notes, Inc., and may not be used in whole or in part without written permission. Cliffs Notes, Inc. Lincoln, Nebraska Page 3 Contents Introduction 5 A Brief Synopsis 5 List of Characters 6 Critical Commentaries Part I 11 Part II 25 Part III 46 Character Analyses 62 Critical Problems 67 Flaubert's Life and Works 72 Suggestions for Further Reading 74 Sample Examination Questions 75 Page 5 Introduction Gustave Flaubert's masterpiece, Madame Bovary, was published in 1857. The book shocked many of its readers and caused a scandalized chain reaction that spread through all France and ultimately resulted in the author's prosecution for immorality. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Pirate and Hacking Speak Because Your Communicating with the World, Tell Them What You Think

Pirate and Hacking Speak Because your communicating with the world, tell them what you think.... ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Afrikaans Poes / Doos - Pussy Fok jou - Fuck you Jy pis my af - You're pissing me off Hoer - Whore Slet - Slut Kak - Shit Poephol - Asshole Dom Doos - Dump Pussy Gaan fok jouself - Go fuck yourself ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Arabic Koos - cunt. nikomak - fuck your mother sharmuta - whore zarba - shit kis - vagina zib - penis Elif air ab tizak! - a thousand "dicks" in your ass! kisich - pussy Elif air ab dinich - A thousand dicks in your religion Mos zibby! - Suck my dick! Waj ab zibik! - An infection to your dick! kelbeh - bitch (lit a female dog) Muti - jackass Kanith - Fucker Kwanii - Faggot Bouse Tizi - Kiss my ass Armenian Aboosh - Stupid Dmbo, Khmbo - Idiot Myruht kooneh - Fuck your mother Peranuht shoonuh kukneh - The dog should shit in your mouth Esh - Donkey Buhlo (BUL-lo) - Dick Kuk oudelic shoon - Shit eating dog Juge / jugik - penis Vorig / vor - ass Eem juges bacheek doer - Kiss my penis Eem voriga bacheek doer - Kiss my ass Toon vor es - You are an ass Toon esh es - You are a jackass Metz Dzi-zik - Big Breasts Metz Jugik - Big penis ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Bengali baing chood - sister fucker chood - fuck/fucker choodmarani - mother fucker haramjada - bastard dhon - dick gud - pussy khanki/maggi - whore laewra aga - dickhead tor bapre choodi - fuck your dad ------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

Philip Roth, Henry Roth and the History of the Jews

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 16 (2014) Issue 2 Article 9 Philip Roth, Henry Roth and the History of the Jews Timothy Parrish Florida State University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Literature Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Parrish, Timothy. "Philip Roth, Henry Roth and the History of the Jews." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.2 (2014): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2411> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

The Proliferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nelson Algren

THE PROLIFERATION OF THE GROTESQUE IN FOUR NOVELS OF NELSON ALGREN by Barry Hamilton Maxwell B.A., University of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department ot English ~- I - Barry Hamilton Maxwell 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Barry Hamilton Maxwell DEGREE: M.A. English TITLE OF THESIS: The Pro1 iferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nel son A1 gren Examining Committee: Chai rman: Dr. Chin Banerjee Dr. Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor - Dr. Evan Alderson External Examiner Associate Professor, Centre for the Arts Date Approved: August 6, 1986 I l~cr'ct~ygr.<~nl lu Sinnri TI-~J.;~;University tile right to lend my t Ire., i6,, pr oJcc t .or ~~ti!r\Jc~tlcr,!;;ry (Ilw tit lc! of which is shown below) to uwr '. 01 thc Simon Frasor Univer-tiity Libr-ary, and to make partial or singlc copic:; orrly for such users or. in rcsponse to a reqclest from the , l i brtlry of rllly other i111i vitl.5 i ty, Or c:! her- educational i r\.;t i tu't ion, on its own t~l1.31f or for- ono of i.ts uwr s. I furthor agroe that permissior~ for niir l tipl c copy i rig of ,111i r; wl~r'k for .;c:tr~l;rr.l y purpose; may be grdnted hy ri,cs oi tiI of i Ittuli I t ir; ~lntlc:r-(;io~dtt\at' copy in<) 01. -

2020-05-25 Prohibited Words List

Clouthub Prohibited Word List Our prohibited words include derogatory racial terms and graphic sexual terms. Rev. 05/25/2020 Words Code 2g1c 1 4r5e 1 1 Not Allowed a2m 1 a54 1 a55 1 acrotomophilia 1 anal 1 analprobe 1 anilingus 1 ass-fucker 1 ass-hat 1 ass-jabber 1 ass-pirate 1 assbag 1 assbandit 1 assbang 1 assbanged 1 assbanger 1 assbangs 1 assbite 1 asscock 1 asscracker 1 assface 1 assfaces 1 assfuck 1 assfucker 1 assfukka 1 assgoblin 1 asshat 1 asshead 1 asshopper 1 assjacker 1 asslick 1 asslicker 1 assmaster 1 assmonkey 1 assmucus 1 assmunch 1 assmuncher 1 assnigger 1 asspirate 1 assshit 1 asssucker 1 asswad 1 asswipe 1 asswipes 1 autoerotic 1 axwound 1 b17ch 1 b1tch 1 babeland 1 1 Clouthub Prohibited Word List Our prohibited words include derogatory racial terms and graphic sexual terms. Rev. 05/25/2020 ballbag 1 ballsack 1 bampot 1 bangbros 1 bawdy 1 bbw 1 bdsm 1 beaner 1 beaners 1 beardedclam 1 bellend 1 beotch 1 bescumber 1 birdlock 1 blowjob 1 blowjobs 1 blumpkin 1 boiolas 1 bollock 1 bollocks 1 bollok 1 bollox 1 boner 1 boners 1 boong 1 booobs 1 boooobs 1 booooobs 1 booooooobs 1 brotherfucker 1 buceta 1 bugger 1 bukkake 1 bulldyke 1 bumblefuck 1 buncombe 1 butt-pirate 1 buttfuck 1 buttfucka 1 buttfucker 1 butthole 1 buttmuch 1 buttmunch 1 buttplug 1 c-0-c-k 1 c-o-c-k 1 c-u-n-t 1 c.0.c.k 1 c.o.c.k. -

University of Regina Archives and Special Collections The

UNIVERSITY OF REGINA ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS THE DR JOHN ARCHER LIBRARY 2012-35 JOAN GIVNER RESARCH AND WRITING ON KATHERINE ANNE PORTER JULY 2012 BY CHELSEA SCHESKE, LYDIA MILIOKAS, ELIZABETH SEITZ AND MICHELLE OLSON REVISED MARCH 2016 BY ELIZABETH SEITZ 2012-35 JOAN GIVNER 2 / 12 Biographical Sketch: Joan Givner (nee Short) graduated from the University of London with a Bachelor of Arts Honours degree in 1958 and a Ph.D. in 1972. She earned a Masters degree in Arts from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri in 1965. While in the United States she taught high school from 1959 until 1961. She then taught English at Port Huron Junior College (now St Clair County Community College) from 1961 until 1965. Givner joined the predecessor of the University of Regina, the University of Saskatchewan, Regina Campus, as a Lecturer of English in 1965 and in 1972 became an Assistant Professor, in 1975 an Associate Professor and in 1981 she became a Professor of English. Joan retired from the University of Regina in 1995 to Victoria, British Columbia and taught creative writing at Malaspina College – Cowichan Campus during the spring of 1997. Joan Givner’s Ph.D. thesis is titled A Critical Study of the Worlds of Katherine Anne Porter (1972), since then, Joan was chosen by Katherine Anne Porter to undertake the task of writing Porter’s biography. Katherine Anne Porter: A Life was published in 1982. Other publications by Givner are Tentacles of Unreason (1985), Katherine Anne Porter: Conversations (1987); Unfortunate Incidents (1988), Mazo de la Roche: The Hidden Life (1989), Katherine Anne Porter: A Life (Revised Edition) (1991), Scenes from Provincial Life (1991), The Self-Portrait of a Literary Biographer (1993), In the Garden of Henry James (1996), Thirty-four Ways of Looking at Jane Eyre: Essays and Fiction (1998) and Half Known Lives (2000). -

The Media Assemblage: the Twentieth-Century Novel in Dialogue with Film, Television, and New Media

THE MEDIA ASSEMBLAGE: THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY NOVEL IN DIALOGUE WITH FILM, TELEVISION, AND NEW MEDIA BY PAUL STEWART HACKMAN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Robert Markley Associate Professor Jim Hansen Associate Professor Ramona Curry ABSTRACT At several moments during the twentieth-century, novelists have been made acutely aware of the novel as a medium due to declarations of the death of the novel. Novelists, at these moments, have found it necessary to define what differentiates the novel from other media and what makes the novel a viable form of art and communication in the age of images. At the same time, writers have expanded the novel form by borrowing conventions from these newer media. I describe this process of differentiation and interaction between the novel and other media as a “media assemblage” and argue that our understanding of the development of the novel in the twentieth century is incomplete if we isolate literature from the other media forms that compete with and influence it. The concept of an assemblage describes a historical situation in which two or more autonomous fields interact and influence one another. On the one hand, an assemblage is composed of physical objects such as TV sets, film cameras, personal computers, and publishing companies, while, on the other hand, it contains enunciations about those objects such as claims about the artistic merit of television, beliefs about the typical audience of a Hollywood blockbuster, or academic discussions about canonicity. -

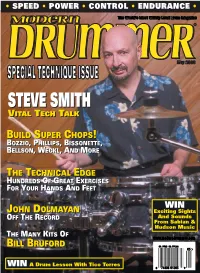

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades.