A History of Cyprus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CYPRUS QUESTION in the MAKING and the ATTITUDE of the SOVIET UNION TOWARDS the CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) a Master's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bilkent University Institutional Repository THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) A Master’s Thesis by MUSTAFA ÇAĞATAY ASLAN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 To my grandfathers Osman OYMAK and Mehmet Akif ASLAN, THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by MUSTAFA ÇAĞATAY ASLAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Associate Prof. Hakan Kırımlı Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Dr. Nur Bilge Criss Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Dr. Eugenia Kermeli Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences --------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) Aslan, Mustafa Çağatay M.A., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Associate Prof. -

CYPRUS Cyprus in Your Heart

CYPRUS Cyprus in your Heart Life is the Journey That You Make It It is often said that life is not only what you are given, but what you make of it. In the beautiful Mediterranean island of Cyprus, its warm inhabitants have truly taken the motto to heart. Whether it’s an elderly man who basks under the shade of a leafy lemon tree passionately playing a game of backgammon with his best friend in the village square, or a mother who busies herself making a range of homemade delicacies for the entire family to enjoy, passion and lust for life are experienced at every turn. And when glimpsing around a hidden corner, you can always expect the unexpected. Colourful orange groves surround stunning ancient ruins, rugged cliffs embrace idyllic calm turquoise waters, and shady pine covered mountains are brought to life with clusters of stone built villages begging to be explored. Amidst the wide diversity of cultural and natural heritage is a burgeoning cosmopolitan life boasting towns where glamorous restaurants sit side by side trendy boutiques, as winding old streets dotted with quaint taverns give way to contemporary galleries or artistic cafes. Sit down to take in all the splendour and you’ll be made to feel right at home as the locals warmly entice you to join their world where every visitor is made to feel like one of their own. 2 Beachside Splendour Meets Countryside Bliss Lovers of the Mediterranean often flock to the island of Aphrodite to catch their breath in a place where time stands still amidst the beauty of nature. -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

The Cowl Vol

Weekend Forecast: Spring! Sunny, near 60 degrees The Cowl Vol. LX No. 19 Providence College - Providence, Rhode Island April 18,1996 Murphy’s Election Controversy Memory the election on March 28, people be Arms presided. A number of witnesses by Theresa Edo ‘96 gan making comments to her concern appeared for both sides of the argu Editor-In-Chief ing further improper practices in the ment. Walsh was additionally repre After a hearing held on Tuesday, campaign. On Saturday, March 30, she sented by Matthew Albanese ’94, and Kept filed a complaint with Mike Dever ’98, April 9, newly elected Student Con his father, Daniel M. Walsh III PC '64. gress Executive Board President, Mike Chairperson of the Committee on Leg- “There were a lot of inconsistencies Walsh ’97, was suspended from his du and flaws in the process,” said Alive ties on Congress until November of Albanese. “The issue was raised about 1996. Until that time Maureen Lyons whether certain students could associ ate with other students. This is a vio by Erin Piorek ‘96 ’97, the newly elected Vice President lation of basic liberties and free News Writer of Student Congress, will preside over the 47th Congress. This action follows speech,” he continued. The Senior Class Giving Program is a an unprecedented legislative process Kateri Walsh, Mike’s mother, also three year program at Providence College within the Student Congress. attended the proceedings and was vis set up to raise money for scholarships and On April 9, The Committee on Leg ibly disturbed. “Their purpose is to in financial aid. -

Ethnopharmacological Survey of Endemic Medicinal Plants in Paphos District of Cyprus

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 13: 1060-68. 2009. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Endemic Medicinal Plants in Paphos District of Cyprus Charalampos Dokos1,*, Charoula Hadjicosta1, Katerina Dokou2, Niki Stephanou3 1Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece 2School of Biology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece 3Pharmaceutical Private Sector, Paphos, Cyprus *Author for Correspondence: Charalampos Dokos, Magnisias 4, Paphos, Cyprus, P.O Box 8025, E-mail [email protected] Issued August 1, 2009 Abstract Paphos district is an unexplored area in the field of ethnopharmacology. Traditional medicine combines a mix of superstitions and beliefs with the therapeutic use of medical plants that grow wild. In this report we discuss the ethnopharmacological, historical and medical aspects of the use of endemic medical plants in the area of Paphos of Cyprus. Paphos is cited in the east region of the island, characterized by its unique flora.. Many plants were used in an unusual way for therapeutic purposes by local people, comprising a significant part of their tradition that accompanies them up to today in their daily life. Keywords: Paphos; Cyprus; ethnopharmacology; ethnobotany; traditional medicine; herbs. Introduction Cyprus is the birthplace of goddess Aphrodite, a crossroad of three regions (Europe, Asia, Africa) and a rapid expanding economical and technological country. As an island, cited in the eastern site of the Mediterranean sea, it has a unique climate that favours many plants to grow all the year. According to Aristotle’s script (It was found that there is a big and high mountain in Cyprus, higher than all its mountains, called Troodos, where many different plants grow, which are useful in medicine. -

The Villas of the Eastern Adriatic and Ionian Coastlands

Chapter 17 The villas of the eastern Adriatic and Ionian coastlands William Bowden (University of Nottingham) Introduction The eastern coasts of the Adriatic and Ionian seas – the regions of Istria, Dalmatia and Epirus – saw early political and military intervention from Rome, ostensibly to combat Illyrian piracy but also to participate in the internecine struggles between Macedonia and its neighbors, sometimes at the request of one or other of the protagonists. Istria fell to Rome in 177 BCE and was ultimately incorporated into regio X (Venetia et Histria) of Italia by Augustus in 7 BCE. After 168 BCE, much of the coast to the south was effectively under Roman control, with merchant shipping able to operate under Roman protection.1 The Illyrian tribes, however, notably the Delmatae, continued to exist in periodic conflict with Rome until they were finally subdued by Octavian (who later took the name of Augustus) from 35-33 BCE. Further to the south, many of the tribes of Epirus sided with the Macedonians against Rome in the Third Macedonian War, consequently suffering significant reprisals at the hands of Aemilius Paullus in the aftermath in 167 BCE. Epirus was formally incorporated within the Roman province of Macedonia after 146 BCE. The founding of Roman colonies in Epirus (at Butrint, Photike, Dyrrhachium, and Byllis), Dalmatia (at Iader, Narona, Salona, Aequum, possibly Senia, and Epidaurum), and Istria (at Tergeste, Parentium, and Pula) is likely to have had a decisive effect on land-holding patterns because land was redistributed -

The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1998 The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity Elena Koumna Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Koumna, Elena, "The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity" (1998). Master's Theses. 3888. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3888 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ORIGINS OF GREEK CYPRIOT NATIONAL IDENTITY by Elena Koumna A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements forthe Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1998 Copyrightby Elena Koumna 1998 To all those who never stop seeking more knowledge ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis could have never been written without the support of several people. First, I would like to thank my chair and mentor, Dr. Jim Butterfield, who patiently guided me through this challenging process. Without his initial encouragement and guidance to pursue the arguments examined here, this thesis would not have materialized. He helped me clarify and organize my thoughts at a time when my own determination to examine Greek Cypriot identity was coupled with many obstacles. His continuing support and most enlightening feedbackduring the writing of the thesis allowed me to deal with the emotional and content issues that surfaced repeatedly. -

Study of the Geomorphology of Cyprus

STUDY OF THE GEOMORPHOLOGY OF CYPRUS FINAL REPORT Unger and Kotshy (1865) – Geological Map of Cyprus PART 1/3 Main Report Metakron Consortium January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1/3 1 Introduction 1.1 Present Investigation 1-1 1.2 Previous Investigations 1-1 1.3 Project Approach and Scope of Work 1-15 1.4 Methodology 1-16 2 Physiographic Setting 2.1 Regions and Provinces 2-1 2.2 Ammochostos Region (Am) 2-3 2.3 Karpasia Region (Ka) 2-3 2.4 Keryneia Region (Ky) 2-4 2.5 Mesaoria Region (Me) 2-4 2.6 Troodos Region (Tr) 2-5 2.7 Pafos Region (Pa) 2-5 2.8 Lemesos Region (Le) 2-6 2.9 Larnaca Region (La) 2-6 3 Geological Framework 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Terranes 3-2 3.3 Stratigraphy 3-2 4 Environmental Setting 4.1 Paleoclimate 4-1 4.2 Hydrology 4-11 4.3 Discharge 4-30 5 Geomorphic Processes and Landforms 5.1 Introduction 5-1 6 Quaternary Geological Map Units 6.1 Introduction 6-1 6.2 Anthropogenic Units 6-4 6.3 Marine Units 6-6 6.4 Eolian Units 6-10 6.5 Fluvial Units 6-11 6.6 Gravitational Units 6-14 6.7 Mixed Units 6-15 6.8 Paludal Units 6-16 6.9 Residual Units 6-18 7. Geochronology 7.1 Outcomes and Results 7-1 7.2 Sidereal Methods 7-3 7.3 Isotopic Methods 7-3 7.4 Radiogenic Methods – Luminescence Geochronology 7-17 7.5 Chemical and Biological Methods 7-88 7.6 Geomorphic Methods 7-88 7.7 Correlational Methods 7-95 8 Quaternary History 8-1 9 Geoarchaeology 9.1 Introduction 9-1 9.2 Survey of Major Archaeological Sites 9-6 9.3 Landscapes of Major Archaeological Sites 9-10 10 Geomorphosites: Recognition and Legal Framework for their Protection 10.1 -

EUROPE in the Year 300

The Euratlas Map of EUROPE in the Year 300 This map shows the countries of Europe, North Africa and Middle East, in the year 300. For consistency reasons, the boundaries and positions of the entities have been drawn as they were on the beginning of the year 300, so far as our knowledge goes. Each entity has a unique colour, but the shade differences are not always perceptible. Map in Latin with English transla- tion. About 500 km 100 km = about 1.3 cm A euratlas Euratlas-Nüssli 2011 English Modern Names of the Cities if Different from the Old Ones Abdera Avdira Lindus Lindos Abydos Nagra Burnu, Çanakkale Lingones Langres Acragas Agrigento Lixus Larache Aduatuca Tongeren Londinium London Aegyssus Tulcea Luca Lucca Aeminium Coimbra Lucentum Alicante Aenus Enez Lucus Augusti Lugo Agathae Agde Lugdunum Lyon Alalia Aléria Lugdm. Convenarum St.-Bertrand-Comminges Albintiglium Ventimiglia Luguvalium Carlisle Altava Ouled Mimoun Lutetia Paris Amasia Amasya Malaca Málaga Amastris Amasra Manazacerta Malazgirt Amathus Ayios Tykhonas Mariana Bastia Airport Amida Diyarbakır Massilia Marseille Ancyra Ankara Mediolanum Milan Anemurion Anamur Mediol. Santonum Saintes Antakira Antequera Melitene Malatya Antiocheia Antakya, Antioch Melitta Mdina, Malta Apamea Kalat el-Mudik Melos Milos Apollonia Pojani Mesembria Nesebar Aquae Sulis Bath Meschista Mtskheta .euratlas.com Aquincum Óbuda, Budapest Miletus Balat Ara Rottweil Mina Relizane Arausio Orange Mogontiacum Mainz Arbela Arbil Mursa Osijek Archelaïs Aksaray Myra Demre Arco Arcos de la Frontera Naïssus Niš http://www Arelate Arelate Narbona Narbonne Argentaria Srebrenik Narona Vid-Metković Argentorate Strasbourg Neapolis Naples Arminium Rimini Nemauso Nîmes Arsinoe Faiyum Nicephorium Ar-Raqqah Artavil Ardabil Nicopolis Preveza-Nicopolis Artaxata Artashat Nicaea İznik Asculum Ascoli Piceno Nicomedia İzmit EMO 1 Aternum Pescara Nineve Mosul Athenae Athens Nisibis Nusaybin Attalia Antalya Numantia Soria, Garray . -

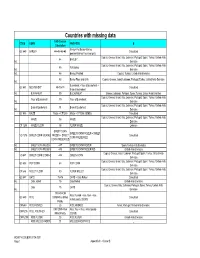

Countries with Missing Data

Countries with missing data FAO Code or CODE GEMS FAO FOOD B Calculation Barley+Pot Barley+Barley, GC 640 BARLEY 44+45+46+48 Calculated pearled+Barley Flour and grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 44 BARLEY Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 45 Pot Barley Int. Emirates Int. 46 Barley, Pearled Cyprus; Turkey; United Arab Emirates 48 Barley Flour and Grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Int. Buckwheat + flour of buckwheat + GC 641 BUCKWHEAT 89+90+91 Calculated Bran of buckwheat Int. BUCKWHEAT 89 BUCKWHEAT Greece; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Flour of Buckwheat 90 Flour of Buckwheat Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Bran of Buckwheat 91 Bran of Buckwheat Int. Emirates GC 645 MAIZE Maize + CF1255 Maize + CF1255 (GEMS) Calculated Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab MAIZE 56 MAIZE Emirates CF 1255 MAIZE FLOUR 58 FLOUR MAIZE Lebanon SWEET CORN SWEET CORN FROZEN + SWEET VO 1275 SWEET CORN (KERNEL FROZEN + SWEET Calculated CORN PRESERVED CORN PRESERVED Int. SWEET CORN FROZEN 447 SWEET CORN FROZEN Spain; United Arab Emirates Int. SWEET CORN PRESERV 448 SWEET CORN PRESERVED United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab VO 447 SWEET CORN (CORN-O 446 GREEN CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab GC 656 POP CORN 68 POP CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab CF 646 MILLET FLOUR 80 FLOUR MILLET Emirates GC 647 OATS 75+76 OATS + Oats Rolled Calculated Int. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

Α ΠΑ- I Σ . A .~riA I ; ΗΛΛΕΡ. ΛΗΞΕΩΣ: j Η,ΜΕΚ KATAXÎ5P.; | ΛΥΞΟΝΑΡ. ΚΛΤΛΧ ............ I j ΥΠΟΓΡΑΦΗ: ...... ..^BiSg^"... i CONSULTANCY SERVÏCËS = I FOR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STUDY I PAFOS SEWERAGE AND I DRAINAGE PROJECT I Preparedfor THE SEWAGE BOARD OF I PAFOS I August 1996 I &?/-BE53-003.FIN Author: I Carole Allen-Morley/Roy Carrier Approved I by: I - M John Colville, Géheral Manager Date I I Howard Humphreys and Partners Ltd (Brown & Root Environmental) Thorncroft Manor I Dorking Road LEATHERHEAD Surrey KT22 8JB I UNITED KINGDOM J A Theophilou I Consulting Engineers Ltd 29 Arch Kyprianou Strovolos, Nicosia I CYPRUS I Brown & Root Environmental I I I I » » I " ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I * The Consultants acknowledge with gratitude the helpful co-operation received from the many • government and other public officers who were consulted in the preparation of this Study. | In particular, the Consultants are grateful to Mr Sawas Sawa and Mr Eftychios Malikides of _ Pafos Municipality for their help and constructive guidance in the identification of issues and ™ in the organisation of field work. I I I I I I I I I I I BE53-003.FIN l1·Ι I ^· ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT I TABLE OF CONTENTS ' Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES-1 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1. Background 1-1 1.2. Objectives 1-1 ι 2. POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK 2-1 • 2.1. Groundwater Protection 2-1 2.2. Surface Water Protection 2-1 1 2.3. Coastal Waters Protection 2-1 2.4. Nature Conservation 2-2 ' 2.5. Noise 2-2 2.6.