The Correspondence of Thomas Merton and Ad Reinhardt: an Introduction and Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (To Be Confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (to be confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS TSM,SH SS TSM, SH Optional/Mandatory Optional Semester(s) MT Contact hour per week 2 contact hours/week; total 22 hours Private study (hours per week) 100 hours Lecturer(s) Justin Doherty ECTs 10 ECTs Aims This module surveys Chekhov’s writing in both short-story and dramatic forms. While some texts from Chekhov’s early period will be included, the focus will be on works from the later 1880s, 1890s and early 1900s. Attention will be given to the social and historical circumstances which form the background to Chekhov’s writings, as well as to major influences on Chekhov’s writing, notably Tolstoy. In examining Chekhov’s major plays, we will also look closely at Chekhov’s involvement with the Moscow Arts Theatre and theatre director and actor Konstantin Stanislavsky. Set texts will include: 1. Short stories ‘Rural’ narratives: ‘Steppe’, ‘Peasants’, ‘In the Ravine’ Psychological stories: ‘Ward No 6’, ‘The Black Monk’, ‘The Bishop’, ‘A Boring Story’ Stories of gentry life: ‘House with a Mezzanine’, ‘The Duel’, ‘Ariadna’ Provincial stories: ‘My Life’, ‘Ionych’, ‘Anna on the Neck’, ‘The Man in a Case’ Late ‘optimistic’ stories: ‘The Lady with the Dog’, ‘The Bride’ 2. Plays The Seagull Uncle Vanya Three Sisters The Cherry Orchard Note on editions: for the stories, I recommend the Everyman edition, The Chekhov Omnibus: Selected Stories, tr. Constance Garnett, revised by Donald Rayfield, London: J. M. Dent, 1994. There are numerous other translations e.g. -

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

O MAGIC LAKE Чайкаthe ENVIRONMENT of the SEAGULL the DACHA Дать Dat to Give

“Twilight Moon” by Isaak Levitan, 1898 O MAGIC LAKE чайкаTHE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SEAGULL THE DACHA дать dat to give DEFINITION датьA seasonal or year-round home in “Russian Dacha or Summer House” by Karl Ivanovich Russia. Ranging from shacks to cottages Kollman,1834 to villas, dachas have reflected changes in property ownership throughout Russian history. In 1894, the year Chekhov wrote The Seagull, dachas were more commonly owned by the “new rich” than ever before. The characters in The Seagull more likely represent the class of the intelligencia: artists, authors, and actors. FUN FACTS Dachas have strong connections with nature, bringing farming and gardening to city folk. A higher class Russian vacation home or estate was called a Usad’ba. Dachas were often associated with adultery and debauchery. 1 HISTORYистория & ARCHITECTURE история istoria history дать HISTORY The term “dacha” originally referred to “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” by the land given to civil servants and war Alphonse Mucha heroes by the tsar. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, and the middle class was able to purchase dwellings built on dachas. These people were called dachniki. Chekhov ridiculed dashniki. ARCHITECTURE Neoclassicism represented intelligence An example of 19th century and culture, so aristocrats of this time neoclassical architecture attempted to reflect this in their architecture. Features of neoclassical architecture include geometric forms, simplicity in structure, grand scales, dramatic use of Greek columns, Roman details, and French windows. Sorin’s estate includes French windows, and likely other elements of neoclassical style. Chekhov’s White Dacha in Melikhovo, 1893 МéлиховоMELIKHOVO Мéлихово Meleekhovo Chekhov’s estate WHITE Chekhov’s house was called “The White DACHA Dacha” and was on the Melikhovo estate. -

Matthew Herrald

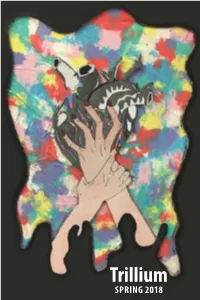

Trillium Issue 39, 2018 The Trillium is the literary and visual arts publication of the Glenville State College Department of Language and Literature Jacob Cline, Student Editor Heather Coleman, Art Editor Dr. Jonathan Minton, Faculty Advisor Dr. Marjorie Stewart, Co-Advisor Dustin Crutchfield, Designer Cover Artwork by Cearra Scott The Trillium welcomes submissions and correspondence from Glenville State College students, faculty, staff, and our extended creative community. Trillium Department of Language and Literature Glenville State College 200 High Street | Glenville, WV 26351 [email protected] http://www.glenville.edu/life/trillium.php The Trillium acquires printing rights for all published materials, which will also be digitally archived. The Trillium may use published artwork for promotional materials, including cover designs, flyers, and posters. All other rights revert to the authors and artists. POETRY Alicia Matheny 01 Return To Expression Jonathan Minton 02 from LETTERS Wayne de Rosset 03 Healing On the Way Brianna Ratliff 04 Untitled Matthew Herrald 05 Cursed Blood Jared Wilson 06 The Beast (Rise and Fall) Brady Tritapoe 09 Book of Knowledge Hannah Seckman 12 I Am Matthew Thiele 13 Stop Making Sense Logan Saho 15 Consequences Megan Stoffel 16 One Day Kerri Swiger 17 The Monsters Inside of Us Johnny O’Hara 18 This Love is Alive Paul Treadway 19 My Mistress Justin Raines 20 Patriotism Kitric Moore 21 The Day in the Life of a College Student Carissa Wood 22 7 Lives of a House Cat Hannah Curfman 23 Earth’s Pure Power Jaylin Johnson 24 Empty Chairs William T. K. Harper 25 Graffiti on the Poet Lauriat’s Grave Kristen Murphy 26 Mama Always Said Teddy Richardson 27 Flesh of Ash Randy Stiers 28 Fussell Said; Caroline Perkins 29 RICHWOOD Sam Edsall 30 “That Day” PROSE Teddy Richardson 33 The Fall of McBride Logan Saho 37 Untitled Skylar Fulton 39 Prayer Weeds David Moss 41 Hot Dogs Grow On Trees Hannah Seckman 42 Of Teeth Berek Clay 45 Lost Beach Sam Edsall 46 Black Magic 8-Ball ART Harold Reed 57 Untitled Maurice R. -

The Good Doctor: the Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (And Others)

Vol. 33, No. 1 11 Literature and the Arts in Medical Education Johanna Shapiro, PhD Feature Editor Editor’s Note: In this column, teachers who are currently using literary and artistic materials as part of their curricula will briefly summarize specific works, delineate their purposes and goals in using these media, describe their audience and teaching strategies, discuss their methods of evaluation, and speculate about the impact of these teaching tools on learners (and teachers). Submissions should be three to five double-spaced pages with a minimum of references. Send your submissions to me at University of California, Irvine, Department of Family Medicine, 101 City Drive South, Building 200, Room 512, Route 81, Orange, CA 92868-3298. 949-824-3748. Fax: 714-456- 7984. E-mail: [email protected]. The Good Doctor: The Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (and Others) Lawrence J. Schneiderman, MD In the spring of 1985, I posted a anything to do with me. “I don’t not possible in this public univer- notice on the medical students’ bul- want a doctor who knows Chekhov, sity; our conference rooms are best letin board announcing a new elec- I want a doctor who knows how to described as Bus Terminal Lite. tive course, “The Good Doctor: The take out my appendix.” Fortunately, The 10 second-year students who Literature and Medicine of Anton I was able to locate two more agree- signed up that first year spent 2 Chekhov.” It was a presumptuous able colleagues from literature and hours each week with me for 10 announcement, since I had never theatre. -

Religious-Verses-And-Poems

A CLUSTER OF PRECIOUS MEMORIES A bud the Gardener gave us, A cluster of precious memories A pure and lovely child. Sprayed with a million tears He gave it to our keeping Wishing God had spared you If only for a few more years. To cherish undefiled; You left a special memory And just as it was opening And a sorrow too great to hold, To the glory of the day, To us who loved and lost you Down came the Heavenly Father Your memory will never grow old. Thanks for the years we had, And took our bud away. Thanks for the memories we shared. We only prayed that when you left us That you knew how much we cared. 1 2 AFTERGLOW A Heart of Gold I’d like the memory of me A heart of gold stopped beating to be a happy one. I’d like to leave an afterglow Working hands at rest of smiles when life is done. God broke our hearts to prove to us I’d like to leave an echo He only takes the best whispering softly down the ways, Leaves and flowers may wither Of happy times and laughing times The golden sun may set and bright and sunny days. I’d like the tears of those who grieve But the hearts that loved you dearly to dry before too long, Are the ones that won’t forget. And cherish those very special memories to which I belong. 4 3 ALL IS WELL A LIFE – WELL LIVED Death is nothing at all, I have only slipped away into the next room. -

Collaborative Effort with SFMOMA Creates Custom Frame Solution for Ad Reinhardt Painting By: Chris Barnett Owner of Sterling Art Services, San Francisco

Collaborative Effort with SFMOMA Creates Custom Frame Solution for Ad Reinhardt Painting by: Chris Barnett Owner of Sterling Art Services, San Francisco A memorable framing project presented itself to us in late 2012: Paula De Cristofaro, the paintings conservator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), contacted me concerning a 1958 Ad Reinhardt painting. With a canvas measuring 40-by-108 inches, the work is encompassed by an artist-made floater frame. Its delicate surface had required some conservation treatment at the SFMOMA conservation laboratory, and to further protect the painting, we were asked to consult on how to glaze it without unduly compromising the viewing experience. A member of the American Abstract Artists, Reinhardt frame face. After testing this approach by mocking up a painted in New York from the 1930s through the ’60s. corner over a small test painting made by De Cristofaro, we His work includes compositions of geometrical shapes to were frustrated to see that this also did not do justice to works in different shades of the same color, including his Reinhardt’s work, as it cast a shadow on the painting. well-known “black” paintings. He also is recognized for his illustrations and comics, and wrote and lectured extensively on the controversial topic “art as art.” Arriving at an appropriate frame design to meet these ends was a collaboration between Sterling Art Services, Zlot- Buell + Associates, and the curatorial and conservation staff at SFMOMA. This is an artwork with such a delicate surface that, unglazed, one must speak and breathe with care in front of it. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Winnovative HTML to PDF Converter for .NET

ARCS homepage The Archival Spirit, February 2012 Newsletter of the Archivists of Religious Collections Section, Society of American Archivists Contents l Letter from the Chair: New ARCS Sparks! l From the Vice-Chair l Archives Workshop in Kenya l DePauw Celebrates 175th Anniversary l Lights, Cameras, Archives in Action: The Diocese of Olympia Archives Begins a Blog! l Christ Church Adds to its Online Database of Records l New Museum Exhibition Links American Artist’s Paintings and Young Pope’s Writings l Web Editor's Note From the Chair: New ARCS Sparks! By Terry Reilly Archivist, University of Calgary This is a creative moment in the world of the Archives of Religious Collections Section. The section has a lot of new energy. We are working ahead on several initiatives while continuing our important role of outreach to new religious archives and archivists. Do you know someone who is just starting out as a religious archivist or someone who is returning to the work after an absence or sabbatical? Encourage them to get in touch with ARCS. We want to incorporate as many new perspectives as we can. Are you associated with a regional religious archivists group? We will be excited to hear what is happening at your area meetings, exhibits or programming plans. Since our annual general meeting in Chicago we have held two steering committee conference calls. We know that regular communication is essential to effective planning. Also, based on your responses at the annual meeting, I have forwarded lists of your interests to members of the steering committee. -

Exibart.Onpaper 18 Sped

FREE Exibart.onpaper 18 Sped. in A.P. 45% art. 2. c. 20 A.P. in Sped. let. B - l. 662/96 Firenze Copia euro 0,0001 arte.architettura.design.musica.moda.filosofia.hitech.teatro.videoclip.editoria.cinema.gallerie.danza.trend.mercato.politica.vip.musei.gossip eventi d'arte in italia | anno terzo | novembre - dicembre 2004 www.exibart.com Un numero così non l'avete mai visto. Ad iniziare dalla cover, come sempre d'autore: questa volta -il tratto urban è inconfondibile- la firmano Botto e Bruno. All'interno quattro chiac- chiere con il fotografo più hot del momento, Terry Richardson. Lo abbiamo incontrato a Bologna, per la presentazione del suo libro. Diario per immagini tenero, scandaloso, sexy, impre- vedibile… ovviamente limited edition. Ve ne diamo un assaggio pepatissimo in una pagina di sole foto. Quelle che nessun'altra rivista (in Italia) ha osato pubblicare. Ricordiamo il filo- sofo Jacques Derida, recentemente scomparso. Senza retorica, due contributi: uno pro ed uno contro. Un'altra pagina la dedichiamo a Donald Judd, papà del Minimal, di cui ricorrono dieci anni dalla morte (anche qui ci sa tanto di essere stati gli unici a ricordarcelo). E a Cristopher Reeve, al mito di Superman e all'immortalità formato celluloide. E ancora. Nuovi spazi che aprono i battenti, overview dalla Biennale di Architettura ed un incontro a tu per tu con Miss Graffiti -al secolo Miss Van- giovane artista di Tolosa che ha firmato la nuova col- lezione della griffe Fornarina. E poi le mostre da non perdere in Italia e all'estero, un giovane designer da tener d'occhio, libri, teatro, parliamo pure di Brian Wilson deus ex machina dei beach Boys, che ha dato alla luce -meglio tardi che mai!- un progetto durato trent'anni. -

Oral History Interview with Ad Reinhardt, Circa 1964

Oral history interview with Ad Reinhardt, circa 1964 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Ad Reinhardt ca. 1964. The interview was conducted by Harlan Phillips for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. This is a rough transcription that may include typographical errors. Interview HARLAN PHILLIPS: In the 30s you were indicating that you just got out of Columbia. AD REINHARDT: Yes. And it was an extremely important period for me. I guess the two big events for me were the WPA projects easel division. I got onto to it I think in '37. And it was also the year that I became part of the American Abstract Artists School and that was, of course, very important for me because the great abstract painters were here from Europe, like Mondrian, Leger, and then a variety of people like Karl Holty, Balcomb Greene were very important for me. But there was a variety of experiences and I remember that as an extremely exciting period for me because - well, I was young and part of that - I guess the abstract artists - well, the American Abstract artists were the vanguard group here, they were about 40 or 50 people and they were all the abstract artists there were almost, there were only two or three that were not members.