Draft July 6, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the First Comprehensive Treatment of Oldenburg's

No. 56 V»< May 31, 1970 he Museum of Modern Art FOR IMT4EDIATE RELEASE jVest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart (N.B. Publication date of book: September 8) CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the first comprehensive treatment of Oldenburg's life and art, will be published by The Museum of Modern Art on September 8, 1970. Richly illustrated with 224 illustrations in black-and-white and 52 in color, this monograph, which will retail at $25, has a highly tactile., flexible binding of vinyl over foam-rubber padding, making it a "soft" book suggestive of the artist's well- known "soft" sculptures. Oldenburg came to New York from Chicago in 1956 and settled on the Lower East Side, at that time a center for young artists whose rebellion against the dominance of Abstract Expressionism and search for an art more directly related to their urban environment led to Pop Art. Oldenburg himself has been regarded as perhaps the most interesting artist to emerge from that movement — "interesting because he transcends it," in the words of Hilton Kramer, art critic of the New York Times. As Miss Rose points out, however, Oldenburg's art cannot be defined by the label of any one movement. His imagination links him with the Surrealists, his pragmatic thought with such American philosophers as Henry James and John Dewey, his handling of paint in his early Store reliefs with the Abstract Expressionists, his subject matter with Pop Art, and some of his severely geometric, serial forms with the Mini malists. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

Collaborative Effort with SFMOMA Creates Custom Frame Solution for Ad Reinhardt Painting By: Chris Barnett Owner of Sterling Art Services, San Francisco

Collaborative Effort with SFMOMA Creates Custom Frame Solution for Ad Reinhardt Painting by: Chris Barnett Owner of Sterling Art Services, San Francisco A memorable framing project presented itself to us in late 2012: Paula De Cristofaro, the paintings conservator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), contacted me concerning a 1958 Ad Reinhardt painting. With a canvas measuring 40-by-108 inches, the work is encompassed by an artist-made floater frame. Its delicate surface had required some conservation treatment at the SFMOMA conservation laboratory, and to further protect the painting, we were asked to consult on how to glaze it without unduly compromising the viewing experience. A member of the American Abstract Artists, Reinhardt frame face. After testing this approach by mocking up a painted in New York from the 1930s through the ’60s. corner over a small test painting made by De Cristofaro, we His work includes compositions of geometrical shapes to were frustrated to see that this also did not do justice to works in different shades of the same color, including his Reinhardt’s work, as it cast a shadow on the painting. well-known “black” paintings. He also is recognized for his illustrations and comics, and wrote and lectured extensively on the controversial topic “art as art.” Arriving at an appropriate frame design to meet these ends was a collaboration between Sterling Art Services, Zlot- Buell + Associates, and the curatorial and conservation staff at SFMOMA. This is an artwork with such a delicate surface that, unglazed, one must speak and breathe with care in front of it. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Oral History Interview with Ad Reinhardt, Circa 1964

Oral history interview with Ad Reinhardt, circa 1964 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Ad Reinhardt ca. 1964. The interview was conducted by Harlan Phillips for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. This is a rough transcription that may include typographical errors. Interview HARLAN PHILLIPS: In the 30s you were indicating that you just got out of Columbia. AD REINHARDT: Yes. And it was an extremely important period for me. I guess the two big events for me were the WPA projects easel division. I got onto to it I think in '37. And it was also the year that I became part of the American Abstract Artists School and that was, of course, very important for me because the great abstract painters were here from Europe, like Mondrian, Leger, and then a variety of people like Karl Holty, Balcomb Greene were very important for me. But there was a variety of experiences and I remember that as an extremely exciting period for me because - well, I was young and part of that - I guess the abstract artists - well, the American Abstract artists were the vanguard group here, they were about 40 or 50 people and they were all the abstract artists there were almost, there were only two or three that were not members. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find e good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Voices in Real Time Interactive and Transmedia Testimonies of the Arab Spring, Instant Archive and New Social Movements Discourses

International PHD Programme in Audiovisual Studies University of Udine, DAMS Gorizia a.a.20 !"20 # Voices in real time Interactive and transmedia testimonies of the Arab Spring, instant archive and new social movements discourses $andidate% &udovica Fales Su)ervisors% *oy Menarini, University of Bologna Ian C,ristie, Bir-.e'- College London 1 /The wor- of our time is to clarify to itself t,e meaning of its o1n desires' 2. Mar3, 'For a Rut,less Criticism of Everyt,ing E3isting' (16!!7 1 2. Mar3, /(or a *ut,less $riticism of 4veryt,ing 43isting,/ in Te Marx- ngles !eader, ed *obert $. 8u'-er, 2nd edition, Ne1 Yor-, W.;. Norton, p. <=6, 12> # 2 I9D4? Introduction "e#ning the research field : transmedia or interactive documentaries% &owards a de#nition of interactive documentaries as '(living( entities )h* is this useful in relation to Tahrir S+uare? xploring the research field. What actions and whose voices% Than-s $,a)ter I – "ocumenting events in the ma-ing toda* 1.1. Documenting collective events in their actuality. A Pre-,istory .,.,., Te formation of the modern public sphere$ actualit* and participation -Te philosophical concept of actualit* - nlightenment as re/ective consciousness on the present -0lashes and fragments of the present time -Actualit* as gathering the present .,.,2 "Te whole world is watching3, Witnessing and showing d*namic in narrating dissent -A new consciousness of news media in the Chicago.567 revolt -"ocumenting and producing media protests (.59:-2::.; - September 1., 2::.. “Te death of detachment( in the news 1.2 Glo.al imagination, actuality, present>tense, real>time .,2,., =lobal imagination, >ocal imagining, A 4ultural Studies &oolbox for Media !epresentation in the =lobal World -=lobal Imagination, Local Imagining -?e*ond '@rientalism'% - Self-narratives, testimonies, micro narratives .,2,2, Te Space of Tahrir S+uare- Within and Without -A Space-in-process -A Space Extended to Tose Watching It -Aerformativit* of Tahrir S+uare - Social Media, Social Change and CitiBen Witnessing – A Faceboo- revolution% .,2,D, Can Tahrir S+uare 2:. -

BARBARA ROSE P.,

The Museum of Modern Art No. 78 BARBARA ROSE p., .. „ Public information Barbara Rose organized LEE KRASNER: A RETROSPECTIVE for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where she is Consulting Curator, and collaborated in its installation at The Museum of Modern Art. She received a B.A. from Barnard College and a Ph.D. in the History of Art from Columbia University. In 1961- 62, she was a Fulbright Fellow to Spain. She has taught at Yale University; Sarah Lawrence and Hunter Colleges; the University of California, Irvine; and was Regent's Professor at the University of California, San Diego. A prominent critic of contemporary art, Miss Rose is currently an associate editor of Arts Magazine and Partisan Review. She was formerly New York correspondent for Art International and a contributing editor to Artforum and Art in America. Her writings have twice received the College Art Associa tion Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinguished Art Criticism. Miss Rose has curated and co-curated many exhibitions, including Claes Oldenburg (1969); Patrick Henry Bruce - An American Modernist (1980); Lee Krasner - Jackson Pollock: A Working Relationship (1980); and Miro in America (1982). She has recently co-authored the exhibition catalogues Leger and the Modern Spirit (1982) and Goya: The "Disasters of War" and Selected Prints from the Collection of the Arthur Roth Foundation (1984). In addition to the catalogue accompanying LEE KRASNER: A RETROSPECTIVE, Miss Rose is the author and editor of American Painting, American Art Since 1900, Readings in American Art, and several monographs. She has also made films on American artists, among them North Star: Mark di Suvero, Sculptor, and Lee Krasner: The Long View, a Cine Film Festival Gold Eagle Recipient in 1980. -

Fame in the Abstract

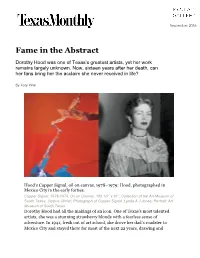

September 2016 Fame in the Abstract Dorothy Hood was one of Texas’s greatest artists, yet her work remains largely unknown. Now, sixteen years after her death, can her fans bring her the acclaim she never received in life? By Katy Vine Hood’s Copper Signal, oil on canvas, 1978–1979; Hood, photographed in Mexico City in the early forties. Copper Signal, 1978-1979, Oil on Canvas, 109 1/2” x 81”; Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi; Photograph of Copper Signal: Lynda A J Jones; Portrait: Art Museum of South Texas Dorothy Hood had all the makings of an icon. One of Texas’s most talented artists, she was a stunning strawberry blonde with a fearless sense of adventure. In 1941, fresh out of art school, she drove her dad’s roadster to Mexico City and stayed there for most of the next 22 years, drawing and painting alongside Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Roberto Montenegro, and Miguel Covarrubias. Pablo Neruda wrote a poem about her paintings. José Clemente Orozco befriended and encouraged her. The Bolivian director and composer José María Velasco Maidana fell hard for her and later married her. And after a brief stretch in New York City, she and Maidana moved to her native Houston, where she produced massive paintings of sweeping color that combined elements of Mexican surrealism and New York abstraction in a way that no one had seen before, winning her acclaim and promises from museums of major exhibits. She seemed on the verge of fame. “She certainly is one of the most important artists from that generation,” said art historian Robert Hobbs. -

Minimalism and Postminimalism

M i n i m a l i s m a n d P o s t m i n i m a l i s m : t h e o r i e s a n d r e p e r c u s s i o n s Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism 4372 The School of the Art Institute of Chicago David Getsy, Instructor [[email protected]] Spring 2000 / Tuesdays 9 am - 12 pm / Champlain 319 c o u r s e de s c r i pt i o n Providing an in-depth investigation into the innovations in art theory and practice commonly known as “Minimalism” and “Postminimalism,” the course follows the development of Minimal stylehood and tracks its far-reaching implications. Throughout, the greater emphasis on the viewer’s contribution to the aesthetic encounter, the transformation of the role of the artist, and the expanded definition of art will be examined. Close evaluations of primary texts and art objects will form the basis for a discussion. • • • m e t h o d o f e va l u a t i o n Students will be evaluated primarily on attendance, preparation, and class discussion. All students are expected to attend class meetings with the required readings completed. There will be two writing assignments: (1) a short paper on a relevant artwork in a Chicago collection or public space due on 28 March 2000 and (2) an in- class final examination to be held on 9 May 2000. The examination will be based primarily on the readings and class discussions. -

The Correspondence of Thomas Merton and Ad Reinhardt: an Introduction and Commentary

Do I want a small painting? The Correspondence of Thomas Merton and Ad Reinhardt: An Introduction and Commentary Roger Lipsey Thomas Merton and Ad Reinhardt met as undergraduates at Co- lumbia University (respectively. Class of 1937 and 1935) and formed a lifelong friendship. Although from wholly different backgrounds, in some ways they were uncannily alike. With their friend, the poet and sage Robert Lax (Class of 1938), and a second friend, the multi-talented editor, writer, and photographer Edward Rice (Class of 1940), they were seekers of truth who never lost touch with one another, however great the geographical distance separating them. Close readers of Thomas Merton have known for years of the Merton-Reinhardt correspondence, published in part and cited where useful to other purposes in the large Merton literature. It has never appeared as a whole, and several brilliant letters have remained unpubhshed. Further, in the absence of context, certain published passages were enigmatic—one had to guess their mean- ing, and it was more sensible not to guess at all. The extant correspondence is just 20 letters, spanning the years 1956 to 1964. This is conceivably the entire correspondence, but that seems unlikely; there are evident gaps and it ends too soon. The first, Reinhardt to Merton, is a catch-up letter—Reinhardt tells Merton what he has been doing in recent years—but it also re- sponds to a request, relayed from Merton through Lax, for a cover design that would suit an instructional pamphlet or series of pam- phlets which Merton was preparing for the novices at the Abbey of Gethsemani.