Robert Motherwell's Interior with Pink Nude

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK Baselitz, De Kooning, Mariscotti, Motherwell, Serra

Upsilon Gallery 404 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 [email protected] www.upsilongallery.com For immediate release BLACK Baselitz, de Kooning, Mariscotti, Motherwell, Serra April 13 – June 3, 2017 Curated by Marcelo Zimmler Spanish Elegy I, Lithograph, on brown HMP handmade paper, 13 3/4 x 30 7/8 in. (35 x 78.5 cm), 1975. Photo by Caius Filimon Upsilon Gallery is pleased to present Black, an exhibition of original and edition work by Georg BaselitZ, Willem de Kooning, Osvaldo Mariscotti, Robert Motherwell and Richard Serra, on view at 146 West 57 Street in New York. Curated by Marcelo Zimmler, the exhibition explores the role played by the color black in Post-war and Contemporary work. In the 1960s, Georg BaselitZ emerged as a pioneer of German Neo–Expressionist painting. His work evokes disquieting subjects rendered feverishly as a means of confronting the realities of the modern age, and explores what it is to be German and a German artist in a postwar world. In the late 1970s his iconic “upside-down” paintings, in which bodies, landscapes, and buildings are inverted within the picture plane ignoring the realities of the physical world, make obvious the artifice of painting. Drawing upon a dynamic and myriad pool of influences, including art of the Mannerist period, African sculptures, and Soviet era illustration art, BaselitZ developed a distinct painting language. Upsilon Gallery 404 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 [email protected] www.upsilongallery.com Willem de Kooning was born on April 24, 1904, into a working class family in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Symposium on the Dura-Europos Synagogue Paintings, in Tribute to Dr

SYMPOSIUM ON THE DURA-EUROPOS SYNAGOGUE PAINTINGS, IN TRIBUTE TO DR. RACHEL WISCHNITZER, NOVEMBER, 1968: THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF MORTON SMITH AND MEYER SCHAPIRO* INTRODUCED AND EDITED BY STEVEN FINE Academic conference lectures often afford important University), and art historian Meyer Schapiro glimpses into the process of academic knowledge (Columbia University), with Rachel Wischnitzer as formation and performance in the period prior moderator.2 Shortly after the symposium, a young to publication. They are environments in which Vivian Mann, then teaching at Wichita State scholars try out new ideas and frequently take University, requested and received a recording of chances without the commitment implicit in pub- the conference, which she recently gave to me. The lication. Conference invitations are often occasions recording, both the original reel and in digitized to enter into and try on new areas of research and form, now resides in the Yeshiva University archives. to formulate work for new audiences. Recordings I am most pleased to present transcripts of two of and transcripts of academic conferences are, thus, the more significant contributions at this conference, important historical sources, reflecting the palimpsest those of Morton Smith and Meyer Schapiro, in this nature of academic composition, presentation, and issue of Images honoring Vivian. publication. When no publication results, they are Morton Smith, (1915–1991), professor of Ancient often the only evidence of the conference having History at Columbia University from 1957 to 1985, taken place and of the learning that took place. was an extremely influential, cutting-edge, and On November 6, 1968 Yeshiva University held often provocative historian of ancient Judaism and a conference on the campus of its Stern College Christianity. -

Collaborative Effort with SFMOMA Creates Custom Frame Solution for Ad Reinhardt Painting By: Chris Barnett Owner of Sterling Art Services, San Francisco

Collaborative Effort with SFMOMA Creates Custom Frame Solution for Ad Reinhardt Painting by: Chris Barnett Owner of Sterling Art Services, San Francisco A memorable framing project presented itself to us in late 2012: Paula De Cristofaro, the paintings conservator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), contacted me concerning a 1958 Ad Reinhardt painting. With a canvas measuring 40-by-108 inches, the work is encompassed by an artist-made floater frame. Its delicate surface had required some conservation treatment at the SFMOMA conservation laboratory, and to further protect the painting, we were asked to consult on how to glaze it without unduly compromising the viewing experience. A member of the American Abstract Artists, Reinhardt frame face. After testing this approach by mocking up a painted in New York from the 1930s through the ’60s. corner over a small test painting made by De Cristofaro, we His work includes compositions of geometrical shapes to were frustrated to see that this also did not do justice to works in different shades of the same color, including his Reinhardt’s work, as it cast a shadow on the painting. well-known “black” paintings. He also is recognized for his illustrations and comics, and wrote and lectured extensively on the controversial topic “art as art.” Arriving at an appropriate frame design to meet these ends was a collaboration between Sterling Art Services, Zlot- Buell + Associates, and the curatorial and conservation staff at SFMOMA. This is an artwork with such a delicate surface that, unglazed, one must speak and breathe with care in front of it. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

FY 15 ANNUAL REPORT August 1, 2014- July 31, 2015

FY 15 ANNUAL REPORT August 1, 2014- July 31, 2015 1 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION FY15 Annual Report THE PHILLIPS [IS] A MULTIDIMENSIONAL INSTITUTION THAT CRAVES COLOR, CONNECTEDNESS, A PIONEERING SPIRIT, AND PERSONAL EXPERIENCES 2 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION FY15 Annual Report FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND DIRECTOR This is an incredibly exciting time to be involved with The Phillips Collection. Duncan Phillips had a deep understanding of the “joy-giving, life-enhancing influence” of art, and this connection between art and well-being has always been a driving force. Over the past year, we have continued to push boundaries and forge new paths with that sentiment in mind, from our art acquisitions to our engaging educational programming. Our colorful new visual identity—launched in fall 2014—grew out of the idea of the Phillips as a multidimensional institution, a museum that craves color, connectedness, a pioneering spirit, and personal experiences. Our programming continues to deepen personal conversations with works of art. Art and Wellness: Creative Aging, our collaboration with Iona Senior Services has continued to help participants engage personal memories through conversations and the creating of art. Similarly, our award-winning Contemplation Audio Tour encourages visitors to harness the restorative power of art by deepening their relationship with the art on view. With Duncan Phillips’s philosophies leading the way, we have significantly expanded the collection. The promised gift of 18 American sculptors’ drawings from Trustee Linda Lichtenberg Kaplan, along with the gift of 46 major works by contemporary German and Danish artists from Michael Werner, add significantly to new possibilities that further Phillips’s vision of vital “creative conversations” in our intimate galleries. -

76 Jefferson Fall Penthouse Art Lending Service Exhibition

The Museum of Modern Art U West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart FOR RELEASE: SEPTEMBER 11, 1975 76 JEFFERSON FALL PENTHOUSE ART LENDING SERVICE EXHIBITION 76 JEFFERSON, an exhibition of 38 works produced at that Lower East Side New York address, is the Fall Penthouse exhibition of the Art Lending Service of The Museum of Modern Art, and will be on view from September 11 through December 1. Because of the large number of artists who have lived and worked in the building, the group of works reflects the diversity of art produced in New York 'during the last 15 years. Works by 18 artists in a variety of styles and mediums are included — abstract and realistic painting, sculpture in various materials, and drawings and prints. In addition, there are silkscreen prints published by Chiron Press, which was also located at 76 Jefferson Street from 1963 to 1967. The exhibition has been organized by Richard Marshall, se lections advisor to the Museum's Art Lending Service, and all of the works are for sale. The artists represented in the exhibition who lived and/or worked at 76 Jefferson Street are Milet Andrejevic, E. H. Davis, John Duff, Mel Edwards, Janet Fish, Valerie Jaudon, Neil Jenney, Richard Kalina, Kenneth Kilstrom, Kobashi, Robert Lobe, Brice Marden, Robert Neuwirth, Steve Poleskie, David Robinson, Ed Shostak, Gary Stephan and Neil Williams. The artists whose Chiron Press prints will be on view are Richard Anuskiewicz, Allan d'Arcangelo, Jim Dine, Rosalyn Drexler, Al Held, Robert Indiana, Alex Katz, Ellsworth Kelly, Nicholas Krushenick, Marisol, Robert Motherwell, Louise Nevelson, James Rosenquist, Saul Steinberg, Ernest Trova, Andy Warhol, Jack Youngerman, and Larry Zox. -

William Baziotes Sketchbooks (Microfilm)

William Baziotes sketchbooks (microfilm) Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... William Baziotes sketchbooks (microfilm) AAA.baziwills Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: William Baziotes sketchbooks (microfilm) Identifier: AAA.baziwills Date: 1933 Creator: Baziotes, William, 1912-1963 Extent: 1 Microfilm reel (2 volumes on partial microfilm reel1) Language: Undetermined . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Lent for microfilming 1998 by John Castagno, a dealer who purchased the sketchbooks at auction. The auctioneer's label (Pennypacker-Andrews Auction Centre, N.Y.) affixed to each cover identifies the sketchbooks: "From -

Theory and Philosophy of Ar T

Theory and Philosophy of Art: Style, Artist, and Society SELECTED PAPERS MEYER SCHAPIRO G EORGE BRAZILLER NEW YORK THEORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF AR T ndemned in perpetuity, he said, to repeat his doubtful successes, the Jtic little landscapes with horsemen, remembered from the African .vels of his youth. In this mood, he undertook the trip to Belgium The Still Life as a Personal Object d Holland, not knowing whether a book would come out of it, A Note on Heidegger and van Gogh hough urged to write by his friends who had enjoyed the brilliance his casual talk on the painters of the past and knew his gifts as a ·iter. He was certain only that the journey would not contribute to his (1968) :, for he felt rightly that his troubles as a painter were lodged too deep thin his personality to be resolved by new inspirations from the past. N HIS ESSAY 0 N The Origin of the Work of Art, Martin Lt this concentrated, solitary experience in a foreign land was a pow [ul reawakening; it stirred his energies as nothing had done before. Heidegger interprets a painting by van Gogh to illustrate the 1 1e accumulated forces of a lifetime were suddenly sparked, and in a I nature of art as a disclosure of truth. He comes to this picture in the course of distinguishing three N months, with an incredible speed, he wrote out this book which presents his gifts better than his paintings, refined as these may be. It modes of being: of useful artifacts, of natural things, and of works of 1ched a greater public and provoked controversies that have not yet fine art. -

Oral History Interview with Ad Reinhardt, Circa 1964

Oral history interview with Ad Reinhardt, circa 1964 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Ad Reinhardt ca. 1964. The interview was conducted by Harlan Phillips for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. This is a rough transcription that may include typographical errors. Interview HARLAN PHILLIPS: In the 30s you were indicating that you just got out of Columbia. AD REINHARDT: Yes. And it was an extremely important period for me. I guess the two big events for me were the WPA projects easel division. I got onto to it I think in '37. And it was also the year that I became part of the American Abstract Artists School and that was, of course, very important for me because the great abstract painters were here from Europe, like Mondrian, Leger, and then a variety of people like Karl Holty, Balcomb Greene were very important for me. But there was a variety of experiences and I remember that as an extremely exciting period for me because - well, I was young and part of that - I guess the abstract artists - well, the American Abstract artists were the vanguard group here, they were about 40 or 50 people and they were all the abstract artists there were almost, there were only two or three that were not members. -

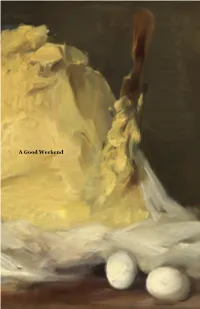

A Good Weekend Cookbook

A Good Weekend A Good Weekend Cookbook Recipes for Various Sweets—and One Potent Cocktail—That Artists Have Created, Utilized, or Simply Enjoyed Over the Past 100 Years Compiled by Andrew Russeth Table of Contents Latifa Echakhch Madeleines au miel 01 Mimi Stone Olive Oil Cake 02 Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec… Rum Punch, Rum Tarte… 04 Mary Cassatt Caramels au Chocolat 06 Norman Rockwell Oatmeal Cookies 07 Grandma Moses Old-Fashioned Macaroons 08 John Cage Almond Cookies 09 Charles Sheeler Shoo-Fly Cake, Molasses Shoo… 10 Roger Nicholson Gunpowder Cake 12 Grant Wood Strawberry Shortcake 13 Karel Appel Cake Barber 15 Sam Francis Schaum Torte 16 Jean Tinguely Omelette Soufflé Dégonflé… 17 Rella Rudoplh Sesame Cookies 18 Frida Kahlo Shortbread Cookies 19 Romare Bearden Bolo Di Rom 20 Richard Estes Aunt Fanny’s English Toffee 22 Alex Katz Sandwich List 23 Robert Motherwell Robert’s Whiskey Cake… 24 Alice Neel Hot-Fudge Sauce 26 George Segal Sponge Cake 27 Tom Wesselmann Banana-Pineapple Bread… 28 An Introduction Since coming across John Cage’s recipe for almond cookies on Greg Allen’s blog a few years ago, I’ve collected recipes associated with artists—dishes they invented, cooked, or just enjoyed—and, much to my surprise, the list has grown quite long. There’s a treasure trove out there! A few examples: Robert Motherwell made rich bittersweet chocolate mousse. Romare Bearden used an old recipe from St. Martin to cook up rum cake. “I don’t do much cooking,” Alice Neel said in 1977. “I’m an artist; I have privileges, you see, that only men had in the past." But she did have a choice recipe for hot-fudge sauce.