Oral History Interview with Leo Castelli, 1969 July

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the First Comprehensive Treatment of Oldenburg's

No. 56 V»< May 31, 1970 he Museum of Modern Art FOR IMT4EDIATE RELEASE jVest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart (N.B. Publication date of book: September 8) CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the first comprehensive treatment of Oldenburg's life and art, will be published by The Museum of Modern Art on September 8, 1970. Richly illustrated with 224 illustrations in black-and-white and 52 in color, this monograph, which will retail at $25, has a highly tactile., flexible binding of vinyl over foam-rubber padding, making it a "soft" book suggestive of the artist's well- known "soft" sculptures. Oldenburg came to New York from Chicago in 1956 and settled on the Lower East Side, at that time a center for young artists whose rebellion against the dominance of Abstract Expressionism and search for an art more directly related to their urban environment led to Pop Art. Oldenburg himself has been regarded as perhaps the most interesting artist to emerge from that movement — "interesting because he transcends it," in the words of Hilton Kramer, art critic of the New York Times. As Miss Rose points out, however, Oldenburg's art cannot be defined by the label of any one movement. His imagination links him with the Surrealists, his pragmatic thought with such American philosophers as Henry James and John Dewey, his handling of paint in his early Store reliefs with the Abstract Expressionists, his subject matter with Pop Art, and some of his severely geometric, serial forms with the Mini malists. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5785 Chapter 2: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Introduction The masters, truth to tell, are judged as much by their influence as by their works. Emile Zola, 18841 Important artists are innovators: they are important because they change the way their successors work. The more widespread, and the more profound, the changes due to the work of any artist, the greater is the importance of that artist. Recognizing the source of artistic importance points to a method of measuring it. Surveys of art history are narratives of the contributions of individual artists. These narratives describe and explain the changes that have occurred over time in artists’ practices. It follows that the importance of an artist can be measured by the attention devoted to his work in these narratives. The most important artists, whose contributions fundamentally change the course of their discipline, cannot be omitted from any such narrative, and their innovations must be analyzed at length; less important artists can either be included or excluded, depending on the length of the specific narrative treatment and the tastes of the author, and if they are included their contributions can be treated more summarily. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Grade Four Session One – the Theme of Modernism

Grade Four Session One – The Theme of Modernism Fourth Grade Overview: In a departure from past years’ programs, the fourth grade program will examine works of art in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in preparation for and anticipation of a field trip in 5th grade to MoMA. The works chosen are among the most iconic in the collection and are part of the teaching tools employed by MoMA’s education department. Further information, ideas and teaching tips are available on MoMA’s website and we encourage you to explore the site yourself and incorporate additional information should you find it appropriate. http://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning! To begin the session, you may explain that the designation “Modern Art” came into existence after the invention of the camera nearly 200 years ago (officially 1839 – further information available at http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dagu/hd_dagu.htm). Artists no longer had to rely on their own hand (painting or drawing) to realistically depict the world around them, as the camera could mechanically reproduce what artists had been doing with pencils and paintbrushes for centuries. With the invention of the camera, artists were free to break from convention and academic tradition and explore different styles of painting, experimenting with color, shapes, textures and perspective. Thus MODERN ART was born. Grade Four Session One First image Henri Rousseau The Dream 1910 Oil on canvas 6’8 1/2” x 9’ 9 ½ inches Collection: Museum of Modern Art, New York (NOTE: DO NOT SHARE IMAGE TITLE YET) Project the image onto the SMARTboard. -

Draft July 6, 2011

Reinhardt, Martin, Richter: Colour in the Grid of Contemporary Painting by Milly Mildred Thelma Ristvedt A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Art History, Department of Art in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen‘s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada Final submission, September, 2011 Copyright ©Milly Mildred Thelma Ristvedt, 2011 Abstract The objective of my thesis is to extend the scholarship on colour in painting by focusing on how it is employed within the structuring framework of the orthogonal grid in the paintings of three contemporary artists, Ad Reinhardt, Agnes Martin and Gerhard Richter. Form and colour are essential elements in painting, and within the ―essentialist‖ grid painting, the presence and function of colour have not received the full discussion they deserve. Structuralist, post-structuralist and anthropological modes of critical analysis in the latter part of the twentieth century, framed by postwar disillusionment and skepticism, have contributed to the effective foreclosure of examination of metaphysical, spiritual and utopian dimensions promised by the grid and its colour earlier in the century. Artists working with the grid have explored, and continue to explore the same eternally vexing problems and mysteries of our existence, but analyses of their art are cloaked in an atmosphere and language of rationalism. Critics and scholars have devoted their attention to discussing the properties of form, giving the behavior and status of colour, as a property affecting mind and body, little mention. The position of colour deserves to be re-dressed, so that we may have a more complete understanding of grid painting as a discrete kind of abstract painting. -

Reflected in the Mirror There Was a Shadow Roy Lichtenstein Andy Warhol

REFLECTED IN THE MIRROR THERE WAS A SHADOW ROY LICHTENSTEIN ANDY WARHOL 1 2 3 4 REFLECTED IN THE MIRROR THERE WAS A SHADOW ROY LICHTENSTEIN ANDY WARHOL November 1 – December 23, 2011 LEO CASTELLI To confront a person with his shadow is to show him his own light. Once one has experienced a few times what it is like to stand judgingly between the opposites, one begins to understand what is meant by the self. Anyone who perceives his shadow and his light simultaneously sees himself from two sides and thus gets in the middle. (Carl Jung, Good and Evil in Analytical Psychology, 1959) Roy Lichtenstein’s new paintings based on mirrors show that he has taken on another broad challenge – that of abstract, invented forms. The Mirror paintings are close to being total abstractions. Nothing recognizable is “reflected” in them, but their surfaces are broken into curving shards of “light,” or angular refractive complexities. They are, in effect elaborately composed pictures of reflections of air. (…) The specific source for the “imagery” of the mirrors is the schematic denotation of reflections and highlights derived from cheap furniture catalogues or small glass company ads. However the distance of Lichtenstein's illusory Mirrors from their sources is so great that the interest is frankly elsewhere. Any tacky connotations (formerly to be cherished) are now dissipated in the paintings’ final fastidious grandeur. (Elizabeth Baker, “The Glass of Fashion and the Mold of Form,” ArtNews, April 1971) Roy Lichtenstein, Paintings: Mirror, 1984 Oil and Magna on canvas, 70 x 86 inches 4 To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow, Creeps in this petty pace from day to day To the last syllable of recorded time, And all our yesterdays have lighted fools This way to dusty death. -

James Rosenquist - Select Chronology

James Rosenquist - Select Chronology THE EARLY YEARS 1933 Born November 29 in Grand Forks, North Dakota. Parents Louis and Ruth Rosenquist, oF Swedish and Norwegian descent. Family settles in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1942. 1948 Wins junior high school scholarship to study art at the Minneapolis School of Art at the Minneapolis Art Institute. 1952-54 Attends the University oF Minnesota, and studies with Cameron Booth. Visits the Art Institute oF Chicago to study old master and 19th-century paintings. Paints storage bins, grain elevators, gasoline tanks, and signs during the summer. Works For General Outdoor Advertising, Minneapolis, and paints commercial billboards. 1955 Receives scholarship to the Art Students League, New York, and studies with Morris Kantor, George GrosZ, and Edwin Dickinson. 1957-59 Becomes a member oF the Sign, Pictorial and Display Union, Local 230. Employed by A.H. Villepigue, Inc., General Outdoor Advertising, Brooklyn, New York, and ArtkraFt Strauss Sign Corporation. Paints billboards in the Times Square area and other locations in New York. 1960s 1960 Quits working For ArtkraFt Strauss Sign Corporation. Rents a loFt at 3-5 Coenties Slip, New York; neighbors include the painters Jack Youngerman, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, Robert Indiana, Lenore Tawney, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Barnett Newman, and the poet Oscar Williamson. 1961 Paints Zone (1960-61), his First studio painting to employ commercial painting techniques and Fragmented advertising imagery. 1962 Has first solo exhibition at the Green Gallery, New York, which he joined in 1961. Early collectors include Robert C. Scull, Count Giuseppe PanZa di Biumo, Richard Brown Baker, and Burton and Emily Tremaine. -

“Robert Morris: the Order of Disorder”, Art in America, May 2010

2% #2%!4)/. 2/"%24 -/22)3 4(% /2$%2 /& $)3/2$%2 Decades after its debutÑand disappearanceÑan early work is re-created by Robert Morris for the gallery that first sponsored it. "9 2)#(!2$ +!,).! This page and next, Robert Morris: Untitled (Scatter ROBERT MORRIS HAS re-created one Morris retrospective, but was not Piece), 1968-69, felt, steel, of the key works of Post-Minimalism, sent to the exhibition’s next venue, lead, zinc, copper, aluminum, Untitled (Scatter Piece), 1968-69, at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Instead, it brass, dimensions variable; at Leo Castelli Gallery, New York. Leo Castelli Gallery on 77th Street. was returned to storage, and subse- Photo Genevieve Hanson. First exhibited along with Continuous quently disappeared—curious, since All works this article © 2010 Project Altered Daily at the Castelli it consisted of 100 hefty pieces of Robert Morris/Artists Rights Warehouse on West 108th Street in metal and 100 pieces of heavy-duty Society (ARS), New York. March 1969, Untitled (Scatter Piece) felt, and weighed about 2 tons. traveled to the Corcoran Gallery of Re-creation, with its implication of exact Art in Washington, D.C., the follow- reproduction, is perhaps an imprecise ing November as part of an early word for the 2010 project. The ele- exist in a perfectly valid iteration while ments in the new work are indeed the in storage—presumably neatly stacked same type as in the original, but rather than strewn about. their disposition (not rule-bound The rectilinear metal pieces are CURRENTLY ON VIEW “Robert Morris: Untitled (Scatter Piece), but arrived at intuitively) responds to made of copper, aluminum, zinc, 1968-69” at Leo Castelli Gallery, New the work’s location: Morris maintains brass, lead or steel, and arrived at York, through May 15. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find e good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

BARBARA ROSE P.,

The Museum of Modern Art No. 78 BARBARA ROSE p., .. „ Public information Barbara Rose organized LEE KRASNER: A RETROSPECTIVE for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where she is Consulting Curator, and collaborated in its installation at The Museum of Modern Art. She received a B.A. from Barnard College and a Ph.D. in the History of Art from Columbia University. In 1961- 62, she was a Fulbright Fellow to Spain. She has taught at Yale University; Sarah Lawrence and Hunter Colleges; the University of California, Irvine; and was Regent's Professor at the University of California, San Diego. A prominent critic of contemporary art, Miss Rose is currently an associate editor of Arts Magazine and Partisan Review. She was formerly New York correspondent for Art International and a contributing editor to Artforum and Art in America. Her writings have twice received the College Art Associa tion Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinguished Art Criticism. Miss Rose has curated and co-curated many exhibitions, including Claes Oldenburg (1969); Patrick Henry Bruce - An American Modernist (1980); Lee Krasner - Jackson Pollock: A Working Relationship (1980); and Miro in America (1982). She has recently co-authored the exhibition catalogues Leger and the Modern Spirit (1982) and Goya: The "Disasters of War" and Selected Prints from the Collection of the Arthur Roth Foundation (1984). In addition to the catalogue accompanying LEE KRASNER: A RETROSPECTIVE, Miss Rose is the author and editor of American Painting, American Art Since 1900, Readings in American Art, and several monographs. She has also made films on American artists, among them North Star: Mark di Suvero, Sculptor, and Lee Krasner: The Long View, a Cine Film Festival Gold Eagle Recipient in 1980. -

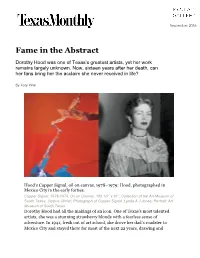

Fame in the Abstract

September 2016 Fame in the Abstract Dorothy Hood was one of Texas’s greatest artists, yet her work remains largely unknown. Now, sixteen years after her death, can her fans bring her the acclaim she never received in life? By Katy Vine Hood’s Copper Signal, oil on canvas, 1978–1979; Hood, photographed in Mexico City in the early forties. Copper Signal, 1978-1979, Oil on Canvas, 109 1/2” x 81”; Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi; Photograph of Copper Signal: Lynda A J Jones; Portrait: Art Museum of South Texas Dorothy Hood had all the makings of an icon. One of Texas’s most talented artists, she was a stunning strawberry blonde with a fearless sense of adventure. In 1941, fresh out of art school, she drove her dad’s roadster to Mexico City and stayed there for most of the next 22 years, drawing and painting alongside Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Roberto Montenegro, and Miguel Covarrubias. Pablo Neruda wrote a poem about her paintings. José Clemente Orozco befriended and encouraged her. The Bolivian director and composer José María Velasco Maidana fell hard for her and later married her. And after a brief stretch in New York City, she and Maidana moved to her native Houston, where she produced massive paintings of sweeping color that combined elements of Mexican surrealism and New York abstraction in a way that no one had seen before, winning her acclaim and promises from museums of major exhibits. She seemed on the verge of fame. “She certainly is one of the most important artists from that generation,” said art historian Robert Hobbs.