Voices in Real Time Interactive and Transmedia Testimonies of the Arab Spring, Instant Archive and New Social Movements Discourses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Most Contagious 2011

MOST CONTAGIOUS 2011 Cover image: Take This LoLLipop / Jason Zada most contagious / p.02 / mosT ConTAGIOUS 2011 / subsCripTion oFFer / 20% disCounT FuTure-prooFing your brain VALid unTiL 9Th JANUARY 2012 offering a saving of £200 gBP chapters / Contagious exists to find and filter the most innovative 01 / exercises in branding, technology, and popular culture, and movemenTs deliver this collective wisdom to our beloved subscribers. 02 / Once a year, we round up the highlights, identify what’s important proJeCTs and why, and push it out to the world, for free. 03 / serviCe Welcome to Most Contagious 2011, the only retrospective you’ll ever need. 04 / soCiaL It’s been an extraordinary year; economies in turmoil, empires 05 / torn down, dizzying technological progress, the evolution of idenTiTy brands into venture capitalists, the evolution of a generation of young people into entrepreneurs… 06 / TeChnoLogy It’s also been a bumper year for the Contagious crew. Our 07 / Insider consultancy division is now bringing insight and inspiration daTa to clients from Kraft to Nike, and Google to BBC Worldwide. We 08 / were thrilled with the success of our first Now / Next / Why event augmenTed in London in December, and are bringing the show to New York 09 / on February 22nd. Grab your ticket here. money We’ve added more people to our offices in London and New 10 / York, launched an office in India, and in 2012 have our sights haCk Culture firmly set on Brazil. Latin America, we’re on our way. Get ready! 11 / musiC 2.0 We would also like to take this opportunity to thank our friends, supporters and especially our valued subscribers, all over the 12 / world. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Top Ico Country Singles

TOP ICO COUNTRY SINGLES November 3, 1984 Weeks Weeks Weeks On On On 10/27 Chart 10/27 Chart 10/27 Chart ^PciTY OF NEW ORLEANS 35 WISHFUL DRINKIN’ YOU TURN ME ON WILLIE NELSON (Columbia 38-04568) 3 12 ATLANTA (MCA-52452) 35 9 ED BRUCE (RCA PB-1 3937) — 1 GIVE ME ONE MORE CHANCE 1 ALL MY ROWDY FRIENDS ARE 69 MAMA SHE’S LAZY © EXILE (Epic 34-04567) 4 13 ^ I COMING OVER PINKARD & BOWDEN (Warner Bros. 7- KB I’VE BEEN AROUND ENOUGH TO HANK WILLIAMS, JR. (Warner Bros. 7- 29205) 51 7 KNOW 29184) 41 S 70 THAT’S EASY FOR YOU TO SAY JOHN SCHNEIDER (MCA-52407) 5 14 TURN ME LOOSE KATHY MATTEA (Mercury 880 192-7) 52 7 O SHE SURE GOT AWAY WITH MY 42 8 71 THE REBEL HEART 38 DON’T YOU GIVE UP ON LOVE JIMMY BUFFETT (MCA-5512) 55 6 JOHN ANDERSON (Warner Bros. 7-29207) 6 12 STEVE WARINER (RCA PB-13768) 40 7 72 THE REBEL FOOL’S GOLD 39 SECOND HAND HEART O NAT STUCKEY (Kristal KS-2275) 76 3 LEE (MCA-52426) 7 12 MORRIS (Warner Bros. 7-29230) 17 15 GREENWOOD GARY 73 STRAIGHT FOR YOUR LOVE 6 IF YOU’RE GONNA PLAY IN TEXAS 40 GOODBYE HEARTACHE BACKWATER (A.M.I. 1917) 56 10 ALABAMA (RCA PB-13840) 1 14 LOUISE MANDRELL (RCA PB-13850) 21 12 CLOSER TO CRAZY ONE TAKES THE BLAME 41 UNCLE PEN ® (A. — O MEMPHIS Rose AR-078) 1 THE STATLERS (Mercury 880 130-7) 11 12 RICKY SKAGGS (Epic 34-04527) 28 16 75 I’VE ALWAYS GOT THE HEART TO YOU COULD’VE HEARD A HEART 42 ROCK AND ROLL SHOES SING THE BLUES O BREAK RAY CHARLES WITH B.J. -

Collaborative Effort with SFMOMA Creates Custom Frame Solution for Ad Reinhardt Painting By: Chris Barnett Owner of Sterling Art Services, San Francisco

Collaborative Effort with SFMOMA Creates Custom Frame Solution for Ad Reinhardt Painting by: Chris Barnett Owner of Sterling Art Services, San Francisco A memorable framing project presented itself to us in late 2012: Paula De Cristofaro, the paintings conservator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), contacted me concerning a 1958 Ad Reinhardt painting. With a canvas measuring 40-by-108 inches, the work is encompassed by an artist-made floater frame. Its delicate surface had required some conservation treatment at the SFMOMA conservation laboratory, and to further protect the painting, we were asked to consult on how to glaze it without unduly compromising the viewing experience. A member of the American Abstract Artists, Reinhardt frame face. After testing this approach by mocking up a painted in New York from the 1930s through the ’60s. corner over a small test painting made by De Cristofaro, we His work includes compositions of geometrical shapes to were frustrated to see that this also did not do justice to works in different shades of the same color, including his Reinhardt’s work, as it cast a shadow on the painting. well-known “black” paintings. He also is recognized for his illustrations and comics, and wrote and lectured extensively on the controversial topic “art as art.” Arriving at an appropriate frame design to meet these ends was a collaboration between Sterling Art Services, Zlot- Buell + Associates, and the curatorial and conservation staff at SFMOMA. This is an artwork with such a delicate surface that, unglazed, one must speak and breathe with care in front of it. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Meditative Story Transcript – Kaywin Feldman

Meditative Story Transcript – Kaywin Feldman Click here to listen to the full Meditative Story episode with Kaywin Feldman. KAYWIN FELDMAN: I don’t even change my clothes. I just head out to make it there in time. It’s close to the center of town, so I don’t have to walk far. I pay my entrance fee and walk in. There are hardly any visitors. The chapel is small and attached to a monastery. The building itself is tall but nothing terribly special. But suddenly I see it: Every inch of wall, floor to ceiling, is painted with a narrative cycle. The first thing I notice is the stillness. I can’t even hear my sneakers on the stone floor. It’s cool inside. Then the glow. The whole room, even the arched ceiling, glows lapis blue from the paint. Inside this still room, my body stills, too. I am in need of sanctuary, and here it is. It feels safe, sacred. It lets me emotionally and intellectually clear my mind, so that I can really look at the frescoes. I’m hardly breathing. My heart rate slows. I can feel my mouth open as I take in the room. ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Kaywin Feldman grew up in a military family, and her childhood memories are dominated by visits to art museums in the various cities and towns where her family moved. You might say she was destined to become a museum director, and at the young age of 28, she achieves just that. Today, Kaywin presides over the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. -

Jesse La-Flair

Jesse La-Flair Gender: Male Mobile: 631-384-4193 Height: 6 ft. 0 in. E-mail: [email protected] Weight: 140 pounds Web Site: http://Http://www.je... Eyes: Blue Hair Length: Regular Waist: 30 Inseam: 33 Shoe Size: 9 Physique: Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 36L Ethnicity: Caucasian / White Photos Film Credits X-Men Dark Phoenix Nightcrawler Stunt Double Guy Norris Captain Marvel Stunt Performer / Wire work Jeff Habberstad Alpha Kodi Smit-Mcphee Stunt Double Brian Machleit X-Men Apocalypse Nightcrawler stunt double Jim Churchman, Jeff Habberstad, Yoga Hosers Hunter stunt double Chad Dashnaw Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Stunts Garrett Warren Divergent Stunts Garrett Warren 300: Rise of an Empire Spartan - Stunts Damon Caro After Earth Stunts R.A. Rondell & Chad Stahelski Zombie War 25ft Low Fall Action Factory Savage Dragon Stunts Victor Lopez,Thayr Harris, Cory Demeyers Generated on 10/01/2021 01:32:54 am Page 1 of 4 Richard King Dark Prophet Soldier - Stunts Brandon Melendy (Stunts) & George Roberson II (Fight choreo) Blood Games Fighter / Monkey Man Jessen Noviello / NXT LVL Sand Sharks Nikki's Boyfriend & Stunts Mark Atkins Don't Idle (Zombie Parkour Seth - STARRING & Stunts Marco Antonio Aguilar Movie) Equinox Freerunner - STARRING Fred Murphy (ASC) Under Penalty Stunts Liam Holland Jobert's Painting Stunts Derrick Judge Early Psycho-Path Malik Geraldine Winters Unicorn parkour stunt double: Kevin J Tim Mikulecky O'connor / Buck Acting role Television Shameless Stunts Eddie Perez Westworld Stunt Performer Mickey Giacomazzi The Goldbergs -

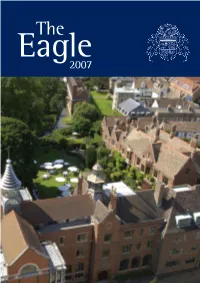

The Eagle 2007 the Eagle 2007

The Eagle 2007 The Eagle 2007 ST JOHN’S COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE The Eagle 2007 The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Articles to be considered for publication should be addressed to: The Editor, The Eagle, Development Office, St John’s College, Cambridge, CB2 1TP. St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP http://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/ General telephone enquiries: 01223 338600 General fax enquiries: 01223 337720 General email enquiries: [email protected] Printed by Cambridge University Press Published by St John’s College, Cambridge, 2007 CONTENTS Message from the Master . 5 Message from the Development Office . 11 Commemoration of Benefactors . 14 Remembering Hugh Sykes Davies . 20 After-dinner Speech by Clifford Evans . 29 A Legal Eagle . 34 Spirit of the Brits . 36 Going Down 1949 . 44 Twenty-five Years of Women at St John’s . 46 Bicentenary of the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade . 49 Hidden in Plain Sight: Slavery and Justice in Rhode Island . 52 St John’s Most Historical Moment? . 63 Book Reviews . 80 Obituaries . 96 College Societies . .125 Photography Competition . 164 College Sports . 172 College Notes . 211 Fellows’ Appointments and Distinctions . 219 Members’ News . 221 Donations to the Library . 283 Errata . 296 MESSAGE FROM THE MASTER There is much to take cheer from in the events of the past year, and it is my privilege to select here a few items for closer scrutiny. I also take the opportunity to make a few valedictory remarks about the College and its future. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

DANNY WATTS Black Boy Meets World

DANNY WATTS Black Boy Meets World LP COMING SOON KEY SELLING POINTS • Entirely produced by Jonwayne • Guest contributions and features include Ray Wright of Warm Brew, DIBIA$E, Leaving Records’ Kiefer, Dr. Octagon collaborator Juan Alderete de la Pena, Zeroh, and many others • The release of Black Boy Meets World will coincide with the Jonwyne’s Rap Album Two US Tour, beginning in October and running for an extended stretch of over 40 dates from coast to coast DESCRIPTION ARTIST: Danny Watts This fall, Danny Watts will release his debut album Black Boy Meets World TITLE: Black Boy Meets World on Jonwayne’s imprint Authors Recording Company. Beats were supplied CATALOG: cd-ARC003 in full by Jonwayne, creating the environments that mesh to Danny Watts’ LABEL: Authors Recording Company introspective lyricism and soulful cadences on the mic. The Houston based GENRE: Hip-Hop/Rap rapper has created a body of work that details his life experiences with an BARCODE: 669158533466 honest and uncompromising lens, jumping out of the Authors Recording FORMAT: CD Company gates as the first release after the critically acclaimed Rap Album HOME MARKET: Texas / Los Angeles Two. Before the release of Black Boy Meets World, Danny Watts is offering RELEASE: 10/6/2017 up the album’s lead single “Young & Reckless” feat. Aye Mitch! today. LIST PRICE: $11.98 / AK Danny Watts and Jonwayne recently captured Black Boy Meets World TRACKLISTING (Click Tracks In Blue To Preview Audio) in the span of only a week, recording the 11-track LP at the Los Angeles recording facility Cosmic Zoo. -

Ikebe Shakedown: Ikebe Shakedown for Information and Soundclips of Our Titles, Go to Street Date: 06/07/2011

UBIQUITY RECORDS PRESENTS IKEBE SHAKEDOWN: IKEBE SHAKEDOWN FOR INFORMATION AND SOUNDCLIPS OF OUR TITLES, GO TO WWW.UBIQUITYRECORDS.COM/PRESS STREET DATE: 06/07/2011 Jed and Lucia HELIUM EP Ikebe Shakedown, the self-titled album from the more like a larger ensemble as increasing layers leap from the tapes. At the other end of the BPM counter, on “Tujunga,” the Brooklyn-based band, plays with elements of band build a gritty African disco jam boasting a floor-filling Cinematic Soul, Afro-funk, Deep Disco, and percussion section, adding seductive guitar licks and an irresistible bass-line to set their horns ablaze. “Tame The Beats” Boogaloo in all the right ways. After spending a is pure fire - bold melodies and heavy rhythms propel the song, few years together the group, named after a with Meters-esque breakdowns providing only brief respite from favorite Nigerian boogie record (and pronounced the action. “ee-KAY-bay,”) delivers a driving set of tunes Some upcoming shows for the band include: May 20th - 7 Inch Release Party - Sullivan Hall, NYC featuring a mighty horn section anchored by tight, June 2nd - Music Frees All Festival - Webster Hall, NYC deep-pocketed grooves. June 3rd - Burlington Jazz Festival - Red Square, Burlington, VT June 9th - Record Release Party - Southpaw, Brooklyn, NY “Right now in cities across the globe, there are plenty of great Afrobeat July 1st - Cornell College - Ithaca, NY revivalist bands aping the sound and groove of Fela Kuti’s legendary sound. July 2nd - Keegan Ales - Kingston, NY Yet, surprisingly few of the new groups have strayed from an orthodox interpretation of the genre or done much real innovation.