Viewed As Art Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Novel Planning Kit Version 03.2020.11

Novel Planning Kit Version 03.2020.11 Created by Terry J. Benton Dear Writers, I started my first manuscript over 10 years ago, and it would take seven more manuscripts and one novella, countless tears and frustration, and lots of effort devoted to studying craft and learning as much as possible before I signed with an agent. Throughout this journey, I’ve enjoyed giving back to the community and helping those who are coming up through the query trenches behind me. I created this Novel Planning Kit from a combination of useful exercises I’ve employed over the last decade to successfully plan fiction novels with the hope that it will assist newer writers on their paths to publication and beyond. There are a plethora of ways to plan, write, and revise a manuscript, and this is just one of thousands of paths available to you—and may not suit your unique needs. I urge you to continue researching widely to find the methods that work best for you and your process. This kit is intended as a FREE resource for writers. Simply print the kit in its entirety and complete the worksheets to begin planning your new novel. Good luck and happy writing! Terry B. | https://www.tjbenton.com | @terryjbenton | @icecreamvicelord TABLE OF CONTENTS Exercise 1: Story Setup Page 2 Build the three cornerstones of your story: hook, challenge, and theme Exercise 2: Conflict Page 3 Identify internal and external conflict for your protagonist, as well as conflicts with minor characters Exercises 3A & 3B: Character Dossier Pages 4 & 5 Develop substantial background for your main and supporting characters Exercise 4: Plot Development Page 6 & 7 Brainstorm major plot points and plot threads for your story Exercise 5: Act Structuring Page 8 Structure your story’s plot across three acts Exercise 6: Pitch Draft Page 9 Draft the first cut of your pitch (or query) Recurring Exercise: Scene Planning Page 10 Recurring exercise for planning and structuring scenes Appendix: Helpful Resources Page 11 Additional helpful paid and free resources Copyright © 2020 by Terry J. -

Empathy and Literary Reading: the Case of Fräulein Else's Interior Monologue

ELISABETHA VINCI - EMPATHY AND LITERARY READING: THE CASE OF FRÄULEIN ELSE’S ..............................................................................................................................................................................INTERIOR MONOLOGUE - doi: https://doi.org/10.25185/6.5 Elisabetha VINCI Università degli Studi di Catania [email protected] ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2680-3832 Recibido: 25/03/2019 - Aceptado: 14/07/2019 Para citar este artículo / To reference this article / Para citar este artigo Vinci, Elisabetha. “Empathy and literary reading: the case of Fräulein Else’s interior monologue”. Humanidades: revista de la Universidad de Montevideo, nº 6, (2019): 133-151. https://doi.org/10.25185/6.5 ISSN: 1510-5024 (papel) - 2301-1629 (en línea) 133 Empathy and literary reading: the case of Fräulein Else’s interior monologue Abstract: This contribution is aimed at analyzing how empathy is instantiated when we read works of fiction and at studying which elements can improve the consonance between characters and readers. Starting from a brief summary about empathy with regard to literary 6, Diciembre 2019, pp. 133-151 texts, the paper examines the question concerning human reception of fictional characters in o order to investigate how we empathize with them through the description of some elements which foster empathy: internal focalization, interior monologue and movement description. Fräulein Else by Arthur Schnitzler will serve as case study of empathic reading. Keywords: empathy, literature, reading, fictional characters, interior monologue. Humanidades: revista de la Universidad Montevideo, N ELISABETHA VINCI - EMPATHY AND LITERARY READING: THE CASE OF FRÄULEIN ELSE’S INTERIOR MONOLOGUE Empatía y lectura literaria: el caso del monólogo interior en Fräulein Else Resumen: El objetivo de esta contribución es analizar cómo la empatía se ejemplifica cuando leemos obras de ficción y estudiar qué elementos pueden mejorar la consonancia de los personajes con los lectores. -

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (To Be Confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (to be confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS TSM,SH SS TSM, SH Optional/Mandatory Optional Semester(s) MT Contact hour per week 2 contact hours/week; total 22 hours Private study (hours per week) 100 hours Lecturer(s) Justin Doherty ECTs 10 ECTs Aims This module surveys Chekhov’s writing in both short-story and dramatic forms. While some texts from Chekhov’s early period will be included, the focus will be on works from the later 1880s, 1890s and early 1900s. Attention will be given to the social and historical circumstances which form the background to Chekhov’s writings, as well as to major influences on Chekhov’s writing, notably Tolstoy. In examining Chekhov’s major plays, we will also look closely at Chekhov’s involvement with the Moscow Arts Theatre and theatre director and actor Konstantin Stanislavsky. Set texts will include: 1. Short stories ‘Rural’ narratives: ‘Steppe’, ‘Peasants’, ‘In the Ravine’ Psychological stories: ‘Ward No 6’, ‘The Black Monk’, ‘The Bishop’, ‘A Boring Story’ Stories of gentry life: ‘House with a Mezzanine’, ‘The Duel’, ‘Ariadna’ Provincial stories: ‘My Life’, ‘Ionych’, ‘Anna on the Neck’, ‘The Man in a Case’ Late ‘optimistic’ stories: ‘The Lady with the Dog’, ‘The Bride’ 2. Plays The Seagull Uncle Vanya Three Sisters The Cherry Orchard Note on editions: for the stories, I recommend the Everyman edition, The Chekhov Omnibus: Selected Stories, tr. Constance Garnett, revised by Donald Rayfield, London: J. M. Dent, 1994. There are numerous other translations e.g. -

Cumulative List of Jury Members For

CUMULATIVE LIST OF PEER ASSESSMENT COMMITTEE MEMBERS FOR THE GOVERNOR GENERAL'S LITERARY AWARDS LISTE CUMULATIVE DES MEMBRES DES COMITÉS D’ÉVALUATION PAR LES PAIRS POUR LES PRIX LITTÉRAIRES DU GOUVERNEUR GÉNÉRAL YEAR CHAIRPERSON ENGLISH SECTION FRENCH SECTION ANNÉE PRÉSIDENT SECTION ANGLAISE SECTION FRANÇAISE 1958 Donald Grant Northrop Frye (Chair/prés.) Guy Sylvestre (Chair/prés.) Robertson Davies Jean-Charles Bonenfant Douglas LePan Robert Élie 1959 Donald Grant Northrop Frye (Chair/prés.) Guy Sylvestre (Chair/prés.) Robertson Davies Jean-Charles Bonenfant Douglas LePan Roger Duhamel 1960 Guy Sylvestre Northrop Frye (Chair/prés.) Roger Duhamel (Chair/prés.) Alfred Bailey Jean-Charles Bonenfant Robertson Davies Clément Lockquell 1961 Guy Sylvestre Northrop Frye (Chair/prés.) Roger Duhamel (Chair/prés.) Alfred Bailey Léopold Lamontagne Roy Daniells Clément Lockquell 1962 Northrop Frye Roy Daniells (Chair/prés.) Roger Duhamel (Chair/prés.) F.W. Watt Léopold Lamontagne Mary Winspear Clément Lockquell 1963 Northrop Frye Roy Daniells (Chair/prés.) Roger Duhamel (Chair/prés.) F.W. Watt Léopold Lamontagne Mary Winspear Clément Lockquell 1964 Roger Duhamel Roy Daniells (Chair/prés.) Léopold Lamontagne (Chair/prés.) F.W. Watt Bernard Julien Mary Winspear Clément Lockquell 1965 Roger Duhamel Roy Daniells (Chair/prés.) Léopold Lamontagne (Chair/prés.) F.W. Watt Bernard Julien Mary Winspear Adrien Thério 1966 Roy Daniells Robert Weaver (Chair/prés.) Léopold Lamontagne (Chair/prés.) Henry Kreisel Jean Filiatrault Mary Winspear Bernard Julien 1967 -

O MAGIC LAKE Чайкаthe ENVIRONMENT of the SEAGULL the DACHA Дать Dat to Give

“Twilight Moon” by Isaak Levitan, 1898 O MAGIC LAKE чайкаTHE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SEAGULL THE DACHA дать dat to give DEFINITION датьA seasonal or year-round home in “Russian Dacha or Summer House” by Karl Ivanovich Russia. Ranging from shacks to cottages Kollman,1834 to villas, dachas have reflected changes in property ownership throughout Russian history. In 1894, the year Chekhov wrote The Seagull, dachas were more commonly owned by the “new rich” than ever before. The characters in The Seagull more likely represent the class of the intelligencia: artists, authors, and actors. FUN FACTS Dachas have strong connections with nature, bringing farming and gardening to city folk. A higher class Russian vacation home or estate was called a Usad’ba. Dachas were often associated with adultery and debauchery. 1 HISTORYистория & ARCHITECTURE история istoria history дать HISTORY The term “dacha” originally referred to “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” by the land given to civil servants and war Alphonse Mucha heroes by the tsar. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, and the middle class was able to purchase dwellings built on dachas. These people were called dachniki. Chekhov ridiculed dashniki. ARCHITECTURE Neoclassicism represented intelligence An example of 19th century and culture, so aristocrats of this time neoclassical architecture attempted to reflect this in their architecture. Features of neoclassical architecture include geometric forms, simplicity in structure, grand scales, dramatic use of Greek columns, Roman details, and French windows. Sorin’s estate includes French windows, and likely other elements of neoclassical style. Chekhov’s White Dacha in Melikhovo, 1893 МéлиховоMELIKHOVO Мéлихово Meleekhovo Chekhov’s estate WHITE Chekhov’s house was called “The White DACHA Dacha” and was on the Melikhovo estate. -

A Rose for Emily”1

English Language & Literature Teaching, Vol. 17, No. 4 Winter 2011 Narrator as Collective ‘We’: The Narrative Structure of “A Rose for Emily”1 Ji-won Kim (Sejong University) Kim, Ji-won. (2011). Narrator as collective ‘we’: The narrative structure of “A Rose for Emily.” English Language & Literature Teaching, 17(4), 141-156. This study purposes to explore the narrative of fictional events complicated by a specific narrator, taking notice of his/her role as an internal focalizer as well as an external participant. In William Faulkner's "A Rose for Emily," the story of an eccentric spinster, Emily Grierson, is focalized and narrated by a townsperson, apparently an individual, but one who always speaks as 'we.' This tale-teller, as a first-hand witness of the events in the story, details the strange circumstances of Emily’s life and her odd relationships with her father, her lover, the community, and even the horrible secret hidden to the climactic moment at the end. The narrative 'we' has surely watched Emily for many years with a considerable interest but also with a respectful distance. Being left unidentified on purpose, this narrative agent, in spite of his/her vagueness, definitely knows more than others do and acts undoubtedly as a pivotal role in this tale of grotesque love. Seamlessly juxtaposing the present and the past, the collective ‘we’ suggests an important subject that the distinction between the past and the present is blurred out for Emily, for whom the indiscernibleness of time flow proves to be her hamartia. The focalizer-narrator describes Miss Emily in the same manner as he/she describes the South whose old ways have passed on by time. -

Matthew Herrald

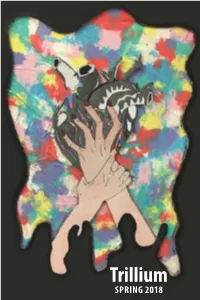

Trillium Issue 39, 2018 The Trillium is the literary and visual arts publication of the Glenville State College Department of Language and Literature Jacob Cline, Student Editor Heather Coleman, Art Editor Dr. Jonathan Minton, Faculty Advisor Dr. Marjorie Stewart, Co-Advisor Dustin Crutchfield, Designer Cover Artwork by Cearra Scott The Trillium welcomes submissions and correspondence from Glenville State College students, faculty, staff, and our extended creative community. Trillium Department of Language and Literature Glenville State College 200 High Street | Glenville, WV 26351 [email protected] http://www.glenville.edu/life/trillium.php The Trillium acquires printing rights for all published materials, which will also be digitally archived. The Trillium may use published artwork for promotional materials, including cover designs, flyers, and posters. All other rights revert to the authors and artists. POETRY Alicia Matheny 01 Return To Expression Jonathan Minton 02 from LETTERS Wayne de Rosset 03 Healing On the Way Brianna Ratliff 04 Untitled Matthew Herrald 05 Cursed Blood Jared Wilson 06 The Beast (Rise and Fall) Brady Tritapoe 09 Book of Knowledge Hannah Seckman 12 I Am Matthew Thiele 13 Stop Making Sense Logan Saho 15 Consequences Megan Stoffel 16 One Day Kerri Swiger 17 The Monsters Inside of Us Johnny O’Hara 18 This Love is Alive Paul Treadway 19 My Mistress Justin Raines 20 Patriotism Kitric Moore 21 The Day in the Life of a College Student Carissa Wood 22 7 Lives of a House Cat Hannah Curfman 23 Earth’s Pure Power Jaylin Johnson 24 Empty Chairs William T. K. Harper 25 Graffiti on the Poet Lauriat’s Grave Kristen Murphy 26 Mama Always Said Teddy Richardson 27 Flesh of Ash Randy Stiers 28 Fussell Said; Caroline Perkins 29 RICHWOOD Sam Edsall 30 “That Day” PROSE Teddy Richardson 33 The Fall of McBride Logan Saho 37 Untitled Skylar Fulton 39 Prayer Weeds David Moss 41 Hot Dogs Grow On Trees Hannah Seckman 42 Of Teeth Berek Clay 45 Lost Beach Sam Edsall 46 Black Magic 8-Ball ART Harold Reed 57 Untitled Maurice R. -

The Good Doctor: the Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (And Others)

Vol. 33, No. 1 11 Literature and the Arts in Medical Education Johanna Shapiro, PhD Feature Editor Editor’s Note: In this column, teachers who are currently using literary and artistic materials as part of their curricula will briefly summarize specific works, delineate their purposes and goals in using these media, describe their audience and teaching strategies, discuss their methods of evaluation, and speculate about the impact of these teaching tools on learners (and teachers). Submissions should be three to five double-spaced pages with a minimum of references. Send your submissions to me at University of California, Irvine, Department of Family Medicine, 101 City Drive South, Building 200, Room 512, Route 81, Orange, CA 92868-3298. 949-824-3748. Fax: 714-456- 7984. E-mail: [email protected]. The Good Doctor: The Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (and Others) Lawrence J. Schneiderman, MD In the spring of 1985, I posted a anything to do with me. “I don’t not possible in this public univer- notice on the medical students’ bul- want a doctor who knows Chekhov, sity; our conference rooms are best letin board announcing a new elec- I want a doctor who knows how to described as Bus Terminal Lite. tive course, “The Good Doctor: The take out my appendix.” Fortunately, The 10 second-year students who Literature and Medicine of Anton I was able to locate two more agree- signed up that first year spent 2 Chekhov.” It was a presumptuous able colleagues from literature and hours each week with me for 10 announcement, since I had never theatre. -

Religious-Verses-And-Poems

A CLUSTER OF PRECIOUS MEMORIES A bud the Gardener gave us, A cluster of precious memories A pure and lovely child. Sprayed with a million tears He gave it to our keeping Wishing God had spared you If only for a few more years. To cherish undefiled; You left a special memory And just as it was opening And a sorrow too great to hold, To the glory of the day, To us who loved and lost you Down came the Heavenly Father Your memory will never grow old. Thanks for the years we had, And took our bud away. Thanks for the memories we shared. We only prayed that when you left us That you knew how much we cared. 1 2 AFTERGLOW A Heart of Gold I’d like the memory of me A heart of gold stopped beating to be a happy one. I’d like to leave an afterglow Working hands at rest of smiles when life is done. God broke our hearts to prove to us I’d like to leave an echo He only takes the best whispering softly down the ways, Leaves and flowers may wither Of happy times and laughing times The golden sun may set and bright and sunny days. I’d like the tears of those who grieve But the hearts that loved you dearly to dry before too long, Are the ones that won’t forget. And cherish those very special memories to which I belong. 4 3 ALL IS WELL A LIFE – WELL LIVED Death is nothing at all, I have only slipped away into the next room. -

James Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz, and Robyn Warhol, Series Editors

THEORY AND INTERPRETATION OF NARRATIVE James Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz, and Robyn Warhol, Series Editors Narrative Theory Core Concepts and Critical Debates DAVID HERMAN JAMES PHELAN PETER J. RABINOWITZ BRIAN RICHARDSON ROBYN WARHOL THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS | COLUMBUS Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Narrative theory : core concepts and critical debates / David Herman ... [et al.]. p. cm. — (Theory and interpretation of narrative) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-5184-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-5184-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-1186-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1186-0 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0-8142-9285-3 (cd-rom) 1. Narration (Rhetoric) I. Herman, David, 1962– II. Series: Theory and interpretation of nar- rative series. PN212.N379 2012 808.036—dc23 2011049224 Cover design by James Baumann Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materi- als. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Part One Perspectives: Rhetorical, Feminist, Mind-Oriented, Antimimetic 1. Introduction: The Approaches Narrative as Rhetoric JAMES PHElan and PETER J. Rabinowitz 3 A Feminist Approach to Narrative RobYN Warhol 9 Exploring the Nexus of Narrative and Mind DAVID HErman 14 Antimimetic, Unnatural, and Postmodern Narrative Theory Brian Richardson 20 2. Authors, Narrators, Narration JAMES PHElan and PETER J. -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Prize Possession: Literary Awards, the GGs, and the CanLit Nation by Owen Percy A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY 2010 ©OwenPercy 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre inference ISBN: 978-0-494-64130-9 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-64130-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY in OLOMOUC Department of English

PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY IN OLOMOUC Department of English and American Studies Marie Voždová The Role of the Narrator in the British Detective Novels of the Golden Age Era Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Pavlína Flajšarová, PhD. Olomouc 2020 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma “The Role of the Narrator in the British Detective Novels of the Golden Age Era” vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucí práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 7. 5. 2020 Podpis: ………………….. 2 Tímto bych chtěla poděkovat Mgr. Pavlíně Flajšarové, PhD. za vedení diplomové práce, za její podněty a trpělivost a také prof. PhDr. Michalu Peprníkovi, Dr. za konzultaci. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 1 The Golden Age of Detective Fiction .................................................................................. 6 1. 1 Issues Concerning the Terminology .............................................................................. 6 1. 2 Characteristics of Detective Novels in the Times of the ‘Golden Age’ ......................... 7 1. 3 Critical Approach to the Detective Fiction ................................................................. 12 2 Notable Novelists of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction .............................................. 17 2. 1 The Detection Club .................................................................................................... 18 2. 2