Proposition 187 and the Ghost of James Bradley Thayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2006

The Old Radio Times The Official Publication of the Old-Time Radio Researchers September 2006 Over 1,450 Subscribers Number 10 Contents How Groucho and his Brothers Left Their Marx on Network Radio Special Features Robert Jennings and Wayne Boenig Marx & Co. 1 The Marx Brothers, and especially the best Bobby Benson 5 known Marx brother, Groucho, had a long and Lost Movies, Pt. 2 7 distinguished career in show business that Researchers Hub 11 spanned two thirds of the Twentieth Century, Aces High 14 and left an indelible mark on the worlds of vaudeville, Broadway theater, movies, radio, Radio Junkie 18 and television. Radio in 1943 20 In addition to being stars together or singly Ex-Lax 23 in all those varied formats, the Marx Brothers Claybourne 26 also exerted an enormous influence thruout the whole of show business during the years they Regular Features were active. Their original vaudeville appearance was shaped by legendary Treasury Report 22 vaudevillian Al Shean of “Gallagher and Crossword 25 Shean.” They were close personal friends with Librarian’s Shelf 27 personalities as varied as Jack Benny, Bob Hope, George S. Kaufman, George Jessell, isn’t exactly the Medici Family for show Buy-Sell-Trade 30 Irving Thalberg, George Burns and Eddie business, at least it is a considerably Letters to the Editor Cantor. In addition Marx family ties were interlinked legacy whose show business 30 interwoven throughout the world of influences are still being felt on down into this Sushi Bar 33 entertainment. Sadye Marx, a cousin, married new century. Jack Benny and became Mary Livingstone. -

Hughes' Budget Up

-.-T Wettiier Distribution 7 *au femysfctat » Oe»*> to*»y *** Mtgbt:*)!)! MUM. Today It* mta. M*.*, kw t. tte 21,800 . Us, tomorrov, cloudy with • nigh to the SM. Wednesday, fair- DIAL SH I-0010 and cold. See Weather, page t ««Ur. Unit anon* rrUw. B««md «ut »MUP RED BANK, N. J., MONDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 1863 VOL. 85, NO. 163 it ill Btlt ui U. MdlUontl MlUlo* Olfleu. 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE City Manager Fired Bowen to Demand Hearing LONG BRANCH- City Manager Richard J. left the city yesterday for a two-week business Bowen was to be in his office at the city hail trip. And Mr. Jones couldn't be reached for annex today. But it may be his last visit there comment. la ait official capacity. '.'".".• ' • One thing that will be held up, undoubtedly, • i He was fired by IU vote of City Council by jytr, Bowen's firing will be introduction of Saturday. Though he will demand a public the 1963 city budget. Council completed work hearing and another vote by the council with-, on Mr. Bowen's recommended budget last week in 30 days, he is not hopeful of returning to: and the manager planned to put all Informs-. the $13,000-a-year job he assumed 18 months ' tion on paper over the weekend and present it ago. ' •'••••••• ^ •... : . • -•:,. for formal drafting by City Auditor Armour His visit today will be merely to pick up- Hulsart. personal belongings. In removing Mm -from "But I've been suspended," Mr. Bowen office, council made" no arrangements- for a pointed, out. -

Jack Benny to Howard Stern

An A-1 Guide to Radio from Jack Benny to Howard Stern RON LACKIUN THE ENCYCLOPEDIA Of AMERICAN RADIO llizdated Edition NELLIE McCLUNG OCT - 4 2001 GRESTE":.. PLI3LIC LIBRARY L 1 tc5914-833 Updated Edition TAE EN(Y(LOPEDIA Of AKER! RAD' An A-1 Guide to Radio from Jack Benny to Howard Stern RON LACKMANN NEL UF- McCLUNG C T- 4 2001 CREATE? PJ3LIL LARK'. Checkmark Books An imprint of Facts On File, Inc. The Encyclopedia of American Radio, Updated Edition Copyright © 1996, 2000 by Ron Lackmann All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Checkmark Books An imprint of Facts On File, Inc. 11 Penn Plaza New York, NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging -in -Publication Data Lackmann, Ronald W. The encyclopedia of American radio : an a -z guide to radio from Jack Benny to Howard Stem / Ron Lackmann-Updated ed. p.cm. Rev. ed. of: Same time, same station. c1996. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4137-7.-ISBN 0-8160-4077-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Radio prograins-United States Encyclopedias.2. Radio programs-Canada Encyclopedias.3. Radio broadcasters-United States Encyclopedias.4. Radio broadcasters-Canada-Encyclopedias. I. Lackmann, Ronald W. Same time, same station.II. Title. PN1991.3.U6L321999 791.44'75'0973-dc21 99-35263 Checkmark Books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. -

America Radio Archive Broadcasting Books

ARA Broadcasting Books EXHIBIT A-1 COLLECTION LISTING CALL # AUTHOR TITLE Description Local Note MBookT TYPELocation Second copy location 001.901 K91b [Broadcasting Collection] Krauss, Lawrence Beyond Star Trek : physics from alien xii, 190 p.; 22 cm. Book Reading Room Maxwell. invasions to the end of time / Lawrence M. Krauss. 011.502 M976c [Broadcasting Collection] Murgio, Matthew P. Communications graphics Matthew P. 240 p. : ill. (part Book Reading Room Murgio. col.) ; 29 cm. 016.38454 P976g [Broadcasting Collection] Public Archives of Guide to CBC sources at the Public viii, 125, 141, viii p. Book Reading Room Canada. Archives / Ernest J. Dick. ; 28 cm. 016.7817296073 S628b [Broadcasting Skowronski, JoAnn. Black music in America : a ix, 723 p. ; 23 cm. Book Reading Room Collection] bibliography / by JoAnn Skowronski. 016.791 M498m [Broadcasting Collection] Mehr, Linda Harris. Motion pictures, television and radio : a xxvii, 201 p. ; 25 Book Reading Room union catalogue of manuscript and cm. special collections in the Western United States / compiled and edited by Linda Harris Mehr ; sponsored by the Film and Television Study Center, inc. 016.7914 R797r [Broadcasting Collection] Rose, Oscar. Radio broadcasting and television, an 120 p. 24 cm. Book Reading Room annotated bibliography / edited by Oscar Rose ... 016.79145 J17t [Broadcasting Collection] Television research : a directory of vi, 138 p. ; 23 cm. Book Reading Room conceptual categories, topic suggestions, and selected sources / compiled by Ronald L. Jacobson. 051 [Broadcasting Collection] TV guide index. 3 copies Book Archive Bldg 070.1 B583n [Broadcasting Collection] Bickel, Karl A. (Karl New empires : the newspaper and the 112 p. -

Image to PDF Conversion Tools

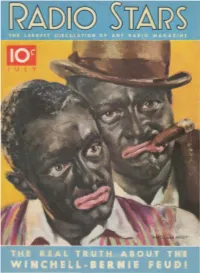

J U L Y Grf!la Garbo I.as sia",'" "onp 10 I,i"cf!s! 11 nd it "8 "I' '0 "fllI 10 sel I... r ri"h'• • Can Vou Solve This MOVIE MIX-UP? HERE'S real fun Mlx·Up today- at the MOVIE MIX'UP, a nearest S. H. Kress fascinating new kind Store or Newsstand. of jig.saw puzzle! It's only lO¢. If you're a movie If you can't get the fan, you'll love it. If MOVIE Mlx·Up you you're a jig.saw fan. want at your Kress you'll get a big kick store or newsstand. out of it. If you're fill out tt:e coupon and Dell PulJli 8 hi n~ Co., Inc. send it with 1O¢ in 100 Fifth Ave., ~ ew York City, N. Y. both (and who isn't?). Please send me the MOI'I K :\1I C't· UI' whi ch 1 hav e cherked below. I am en you'll get a double stamps or coin (l5¢ dosing 10¢ in slamps or ('oin for each one desired (IS¢ apie<:e for C D Tladian ~~ break! in Canada. coin only) coin only), for each MovlE MIX. o NORMA SHEAltER Try it tonight! And o GARY COOPER Up desired. o GRETA GARBO see how long it takes o CLAItK GAI\LE you to put your star Prinl N AME here .•.. ••. •• . .. ......•.. _. together. Get a MOVIE MOVIE MIX-UP.' STREET A onKESS • • •••••••••• .. ••••••••• • CITl' •• • ••• .••••••••••• ••• STATI': , • • •••• • • RADIO STARS THESCOTT~: RADIO delivers such Clear. Consisfent Year 'Round WOR ION ~1lTmI1. -

King Kong and the Human Fly Meaghan Morris

Sexuality & Space Beatriz Colomina, editor Jennifer Bloomer Victor Burgin Elizabeth Grosz Catherine Ingraham Meaghan Morris Laura Mulvey Molly Nesbit Alessandra Ponte Lynn Spigel Patricia White Mark Wigley PRINCETON PAPERS ON ARCHITECTURE Sexuality and Space is the first volume in the series Princeton Papers on Architecture Princeton University School of Architecture Princeton, New Jersey 08544-5264 Editor: Beatriz Colomina Copy Editor: Phil Mariani Designer: Ken Botnick Project Coordinator: Lisa A. Simpson Published by Princeton Architectural Press 37 East 7th Street New York, New York 10003 212.995.9620 © 1992 Princeton Architectural Press All rights reserved 95 94 93 4 3 Printed and bound in Mexico No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sexuality & space I Beatriz Colomina, editor. p. em. -(Princeton papers on architecture: 1) Proceedings of a symposium, held at Princeton University School of Architecture March 10-11, 1990. ISBN 1-878271-o8-3 (paper) : $14.95 1. Space (Art)-Congresses. 2. Space (Architecture)-Congresses. 3. Sexuality in art-Congresses. 4· Arts, Modern-2oth century-Congresses. I. Colomina, Beatriz. II. Title: Sexuality and space. III. Series. NX65o.S8S48 1992 720'. 1-dczo Contents Meaghan Morris I Great Moments in Social Climbing: King Kong and the Human Fly Laura Mulvey 53 Pandora: Topographies of the Mask and Curiosity Beatriz Colomina 73 The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism -

From Scat to Satire

FROM SCAT TO SATIRE: TOWARD A TAXONOMY OF HUMOR IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN MEDIA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY BRIAN BOSWELL JOSEPH MISIEWICZ BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 13, 2009 From Scat to Satire 2 Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 List of Tables 3 Dedication 4 Acknowledgement 5 Abstract 6 Chapter I: Introduction 7 Chapter II: Review of Literature 18 Chapter III: Methods 28 Chapter IV: Analysis of Results 38 Chapter V: Discussion 53 Bibliography 59 Appendix A. Humor Instances in Some Like It Hot 61 Appendix B. Humor Instances in Dr. Strangelove 91 Appendix C. Humor Instances in Annie Hall 109 Appendix D. Humor Instances in Tootsie 128 Appendix E. Humor Instances in There’s Something About Mary 153 From Scat to Satire 3 List of Tables and Charts Table 1 – List of Zero Points 36 Table 2 – Terminology Used in the Analysis of the Films 51 Table 3 – Quantitative Results of the Films 52 Chart 1 – Result of Limiting the Nomadic Traits of Personality Comedians 32 From Scat to Satire 4 Dedication I would like to dedicate this volume to my wife Jennifer, the child we are expecting in September, and my daughter Molly, (who enjoys telling the joke: ―What tree can you hold in your hand? It‘s a palm tree.‖) Their encouragement, patience and inspiration have enabled me to persevere in both this thesis and my graduate studies overall. From Scat to Satire 5 Acknowledgements I would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr. -

Fanny Brice and the “Schnooks” Strategy: Negotiating a Feminine Comic Persona on the Air

Michele Hilmes Fanny Brice and the “Schnooks” Strategy: Negotiating a Feminine Comic Persona on the Air No one could claim that the career of Fanny Brice here is Kate Smith—in a system that preferred has been overlooked. Frequently in the news its female stars as secondary sidekicks (Mary during her long career—more for her private than Livingstone to Jack Benny, Portland Hoffa to Fred her professional life—she has been the subject Allen), relatively humorless “straight women” to of three biographies, numerous popular articles, their partner’s comic lead (Molly in Fibber McGee and several major motion pictures.1 The fact that and Molly), or as the recurring “dumb dora” of most of these efforts have stirred controversy only vaudeville mixed-pair comics (most famously, seems to reflect the tempestuous and contradictory Gracie Allen). Within this carefully delimited life of their heroine, whose career from ethnic containment of the disruptive potential of women’s burlesque to legitimate stage to radio spans more humor, Brice stands out. In her early years on than thirty years and three dramatic marriage-and- NBC in the Chase and Sanborn Hour (1933) divorce scenarios. Amidst the drama of Brice’s and on the Ziegfeld Follies of the Air (CBS 1936) life, and the colorful anecdotes of her role in Brice’s was a woman’s voice speaking humorous the lives of such showmen as Florenz Ziegfeld and sometimes bawdy lines, directing attention and Billy Rose, her most enduring contribution both to her gender and to her ethnicity, defying to popular entertainment—the comic character bounds of taste and appropriate feminine behavior. -

The Oxford Dictionary of Modern Quotations.TXT

The Oxford Dictionary of Modern Quotations PREFACE Preface =-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=- This is a completely new dictionary, containing about 5,000 quotations. What is a "quotation"? It is a saying or piece of writing that strikes people as so true or memorable that they quote it (or allude to it) in speech or writing. Often they will quote it directly, introducing it with a phrase like "As ---- says" but equally often they will assume that the reader or listener already knows the quotation, and they will simply allude to it without mentioning its source (as in the headline "A ros‚ is a ros‚ is a ros‚," referring obliquely to a line by Gertrude Stein). This dictionary has been compiled from extensive evidence of the quotations that are actually used in this way. The dictionary includes the commonest quotations which were found in a collection of more than 200,000 citations assembled by combing books, magazines, and newspapers. For example, our collections contained more than thirty examples each for Edward Heath's "unacceptable face of capitalism" and Marshal McLuhan's "The medium is the message," so both these quotations had to be included. As a result, this book is not--like many quotations dictionaries--a subjective anthology of the editor's favourite quotations, but an objective selection of the quotations which are most widely known and used. Popularity and familiarity are the main criteria for inclusion, although no reader is likely to be familiar with all the quotations in this dictionary. The book can be used for reference or for browsing: to trace the source of a particular quotation or to find an appropriate saying for a special need. -

The Maine Broadcaster Local History Collections

Portland Public Library Portland Public Library Digital Commons The Maine Broadcaster Local History Collections 4-1948 The Maine Broadcaster : April 1948 (Vol. 4, No. 4) Maine Broadcasting System (WCSH Portland, ME) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/mainebroadcaster TBE ~~-~~ BROADCASTING MAINE BROADCASTER~_,/SYSTEM\ A fflllat" PUBLISHED AS AN AID TO BEITER RADIO LISTENING Vol. IY, No. 4, P ortland, M.aine. A pril. 1948 Price, Five Cents TOSCANINI -TO CELEBRATE TENTH YEAR ON NBC " My Philosophy In Rhyme" Maestro Completes Decade Of Great ---·Whe·, n Troubles Are Knocking At Your Door··· By Symphony Music U~CI.Jt H EZZIE Q. S1 OW \\ ·hen troubles hit ya awful hard, Arturo Tusc:mini \\'ill cclcbrntc the much more so than before, completion of his tenth full season as Twul\t du ya one darn bic of good conductor of the NBC Sy mphony to•lav down on the floor OrcheHm with the prescnrntion of And pou.nd )' a head and kick ya feet Hecth01·cn's "Nint h Symphony" Sat and groan with all y:1 might; urday, April 3, over \VCSH, \VRDO Go out and cake a nice bdsk walk, and \VLBZ (6:30 to 7:30 p. m.) things wilJ curn ouc all right. Robert Shaw's Collegiate Chorale There's nothing any bencr when will be heard with che N BC Sym troubles hie ya hard, phony Orchestra. Anne McKnight, Than getting out and walking around siprano; J ane H obson, mczzosopraoo, your own barnyard, :rnd Norman Scott bass, w ill sing the Or if ya from the city, go walking in solo parts. -

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection NMAH.AC.0269 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. and Wendy Shay 2001 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Correspondence, 1932-1977, undated..................................................... 6 Series 2: Publications, Manuscripts, and Print Articles by Marx, 1930-1958, undated .................................................................................................................................. 8 Series 3: Scripts and Sketches, 1939-1959, undated............................................. -

Americanlegionma871amer.Pdf (9.739Mb)

. THE AMERICAN 20c. JULY 1969 MAGAZINE THE RUCKUS OVER THE CENSUS . E YOU LAUGHING AT? u,/ Goodman Ace ETHAN ALLEN , . ^ERU^ONT^S WILD GfAN"^ fE YOU INVITIMG BURGLARS?! markable at this low price. A' revd- . ^utionary new watch . from Switzer- land with features, never" before found in a tinrte piece. Easiest watch- in the world to tell time—three ^sepa- jrate windows—one flashes the .exact 'minute; one shows the precise hour; pne indicates the date — and-;—-a sweep second hand to indicate 1:he sreconds. Here's the watch that's :made to last; extra good io'oks in luxurious" goldtone case and genuine lizzard leather strap. Cqmes gift xed, too. LOOK AT THESE FEATURES 'Telisyou the exact hour. Tells you the exact minute. .£1 Telisyou the exact day. Jells you the exact second. MONEY BACK GUARANTEE GUARANTEE ELECTRONICS INTERNATIONAL, Inc., Dept. DW-1 AGAINST ALL FACTORY DEFECTS 210 S. Despiaines St., Chicago, III. 60606 Please rush on money back guarantee 1. Guaranteed anti-magnetic Computer Age watches @ $19.95 each, Postage and Insur- 2. Guaranteed scratch resistant ance prepaid. I enclose full payment to save postage and 3. Guaranteed unbreakable mainspring C.O.D. fees. n Send C.O.D. I enclose $1.00 goodwill deposit, 4. Guaranteed shock-resistant n Charge to my Diners Club Acct. No.. Charge to my American Express Acct. No.. NAME ADDRESS_ ELECTRONICS INTERNATI Dept. DW-1 ui CITY _STATE_ .ZIP_ 210 S. Despiaines St., Chicago. III. 608M : The American JULY 1969 Volume 87, Number 1 CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Nolify Circulation Dept., I'.