ED378092.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Research and writing: Michal Belikoff and Safa Ali Agbaria Editing: Shirley Racah Steering committee: Samah Elkhatib-Ayoub, Ron Gerlitz, Azar Dakwar, Mohammed Khaliliye, Abed Kanaaneh, Jabir Asaqla, Ghaida Rinawie Zoabi, and Shirley Racah Critical review and assistance with research and writing: Ron Gerlitz and Shirley Racah Academic advisor: Dr. Nahum Ben-Elia Co-directors of Sikkuy’s Equality Policy Department: Abed Kanaaneh and Shirley Racah Project director for Injaz: Mohammed Khaliliye Hebrew language editing: Naomi Glick-Ozrad Production: Michal Belikoff English: IBRT Jerusalem Graphic design: Michal Schreiber Printed by: Defus Tira This pamphlet has also been published in Arabic and Hebrew and is available online at www.sikkuy.org.il and http://injaz.org.il Published with the generous assistance of: The European Union This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Sikkuy and Injaz and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The Moriah Fund UJA-Federation of New York The Jewish Federations of North America Social Venture Fund for Jewish-Arab Equality and Shared Society The Alan B. -

IATF Fact Sheet: Religion

1 FACT SHEET iataskforce.org Topic: Religion – Druze Updated: June 2014 The Druze community in Israel consists of Arabic speakers from an 11th Century off-shoot of Ismaili Shiite theology. The religion is considered heretical by orthodox Islam.2 Members of the Druze community predominantly reside in mountainous areas in Israel, Lebanon, and Syria.3 At the end of 2011, the Druze population in Israel numbered 133,000 inhabitants and constituted 8.0% of the Arab and Druze population, or 1.7%of the total population in Israel.4 The Druze population resides in 19 localities located in the Northern District (81% of the Druze population, excluding the Golan Heights) and Haifa District (19%). There are seven localities which are exclusively Druze: Yanuh-Jat, Sajur, Beit Jann, Majdal Shams, Buq’ata, Mas'ade, and Julis.5 In eight other localities, Druze constitute an overwhelming majority of more than 75% of the population: Yarka, Ein al-Assad, Ein Qiniyye, Daliyat al-Karmel, Hurfeish, Kisra-Samia, Peki’in and Isfiya. In the village of Maghar, Druze constitute an almost 60% majority. Finally, in three localities, Druze account for less than a third of the population: Rama, Abu Snan and Shfar'am.6 The Druze in Israel were officially recognized in 1957 by the government as a distinct ethnic group and an autonomous religious community, independent of Muslim religious courts. They have their own religious courts, with jurisdiction in matters of personal status and spiritual leadership, headed by Sheikh Muwaffak Tarif. 1 Compiled by Prof. Elie Rekhess, Associate Director, Crown Center for Jewish and Israel Studies, Northwestern University 2 Naim Araidi, The Druze in Israel, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, December 22, 2002, http://www.mfa.gov.il; Gabriel Ben Dor, “The Druze Minority in Israel in the mid-1990s”, Jerusalem Letters, 315, June 1, 1995, JerusalemCenter for Public Affairs. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

The Sikkuy Report 2003-2004

SIKKUY: THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE Sikkuy ÈÂÎÈÒ ADVANCEMENT OF CIVIC EQUALITY IN ISRAEL Sikkuy (a “chance” or “opportunity" in Hebrew) is a non-partisan, non-profit, NGO Sikkuy ÈÂÎÈÒ The SikkuyReport2003-2004 Executive Summary in Israel that develops and implements projects to advance civic equality between Arab See p. 11 ÈÁ¯Ê‡†ÔÂÈ¢†Ì„Șφ‰˙ÂÓÚ‰ and Jewish citizens of Israel in government budgets, resource allocation, hiring policy, The Association for the Advancement of Civic Equality land usage etc. Founded in 1991 as a Jewish-Arab advocacy organization, Sikkuy's actions are motivated by the right of every citizen to influence government decisions and policies. Sikkuy is an active member of the international civil society community and is dedicated to advancing civil society in Israel through the values of: The Sikkuy Report EQUALITY - Advancing complete equality between Arab and Jewish citizens. SHARED CITIZENSHIP - Promoting the core value of citizenship as the basis for equality. HUMAN DIGNITY - Mainstreaming human dignity as the supreme value in 2003-2004 relations between the citizen and the state and the state and its citizens. Monitoring Civic Equality Between Sikkuy is jointly governed by Arab and Jewish co-chairs, managed by two Arab and Jewish co-directors and staffed by Arabs and Jews. Sikkuy's programs are Arab and Jewish Citizens of Israel aimed at mobilizing a transformation of the relations between the state and the Arab minority in Israel. They include: The Or Commission recommendations: one year later OR COMMISSION WATCH - To monitor and advance the Or Commission's Gaps between Jewish and Arab citizens of Israel in institutional recommendations for implementing civic equality between Arab and education, health, income, employment and poverty Jewish citizens. -

From Barriers to Opportunities Mapping the Barriers and Policy Recommendations for Achieving Equality Between the Arab and Jewish Citizens of Israel

Barriers to equality policy toward the Arab citizens – a model for mapping, characterization and analysis Mapping barriers and policy recommendations: The Legal Aid Offices of the Justice Ministry Out-of-home frameworks for children at risk from birth to age 3 SI KK This paper presents a structured and comprehensive model to map, U Y // F classify and characterize barriers preventing the State of Israel from providing equal access to government resources for Arab citizens. The model also presents methodology to create policy recommendations for ROM removing the barriers and achieving equality. In addition, it includes two B policy papers in which the model is applied: one on the subject of the ARRIERS legal aid services of the Justice Ministry, and the second on the subject of out-of-home frameworks for children at risk. In each of those areas the principal barriers were mapped and policy recommendations were made for eliminating them. Development and application of the model were carried TO out in within the Seat At The Table project, which is run by the Equality OPPORTUNITIES FROM BARRIERS Policy Department of Sikkuy. We hope that the knowledge and insights that we are making available to the readers will be of help to all those who are working to promote equality between Jews and Arabs in Israel. TO OPPORTUNITIES Mapping the barriers and policy recommendations Sikkuy – The Association for the Advancement of Civic Equality // for achieving equality between the Arab and Jewish citizens of Israel is a civil society organization, shared by Jews and Arabs who are citizens of Israel, whose goal is to promote a substantive change in the status of the PO L Arab citizens of Israel. -

INSTITUTE of JERUSALEM STUDIES JERUSALEM of INSTITUTE Autumn 2019

The Suppression of the Great Revolt and the Destruction of Everyday Life in Palestine Charles Anderson Resistance and Survival in Central Galilee, July 1948–July 1951 Adel Manna Building to Survive: The Politics of Cement in Autumn 2019 Mandate Palestine Nimrod Ben Zeev Autumn 2019 To Subvert, To Deconstruct: Agency in Qalandiya Refugee Camp Ahmed Alaqra Thurayya’s Wedding: A Glimpse of Ottoman Jerusalem from the Khalidi Library Khader Salameh INSTITUTE OF JERUSALEM STUDIES Editors: Beshara Doumani and Salim Tamari Executive Editor: Alex Winder Managing Editor: Carol Khoury Consulting Editor: Issam Nassar Editorial Committee: Rana Barakat, Rema Hammami, Penny Johnson, Nazmi al-Ju’beh, Roberto Mazza Advisory Board: Rochelle Davis, Georgetown University, U. S. Michael Dumper, University of Exeter, U. K. Rania Elias, Yabous Cultural Centre, Jerusalem George Hintlian, Christian Heritage Institute, Jerusalem Huda al-Imam, Imam Consulting, Jerusalem Hassan Khader, al-Karmel Magazine, Ramallah Rashid Khalidi, Columbia University, U. S. Yusuf Natsheh, al-Quds University, Jerusalem Khader Salameh, al-Khalidi Library, Jerusalem Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Queen Mary University of London, U. K. Tina Sherwell, Birzeit University, Birzeit Contributing Editors: Yazid Anani, A. M. Qattan Foundation, Ramallah Khaldun Bshara, RIWAQ Centre, Ramallah Sreemati Mitter, Brown University, U. S. Falestin Naili, Institut français du Proche-Orient (Ifpo), Jordan Jacob Norris, University of Sussex, U. K. Mezna Qato, University of Cambridge, U. K. Omar Imseeh Tesdell, Birzeit University, Birzeit Hanan Toukan, Bard College Berlin, Germany The Jerusalem Quarterly (JQ) is the leading journal on the past, present, and future of Jerusalem. It documents the current status of the city and its predicaments. -

Table of Contents

February 16, 2014 Table of Contents From the Editor’s Desk ............................................................................ 2 Editorials .................................................................................................... 5 Nohad Ali / The Significance of the Islamic Movement’s Abstention in Israel’s Municipal Elections ................................................................................................... 5 Ziyad Abu Habla / The Arab Local Governments in Israel: Moving Toward Economic Independence ............................................................................................ 9 Nadia Hilou / Reflections on the Results of the Local Elections in Jaffa ................ 13 The major issues in the local election campaign .................................. 16 General summary of the election campaign ............................................................. 16 The role of clans and clan-based affiliations in municipal politics ......................... 19 The election campaign in Nazareth .......................................................................... 20 The Islamic Movement after the local elections ...................................................... 21 Mixed cities: Success in Upper Nazareth, failure in Jaffa ....................................... 22 Results of the 2013 elections ................................................................... 23 Election results in Arab and Druze localities ........................................................... 23 The Galilee -

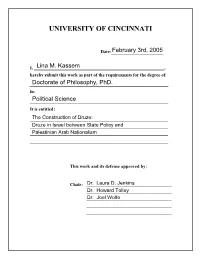

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Construction of Druze Ethnicity: Druze in Israel between State Policy and Palestinian Arab Nationalism A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2005 by Lina M. Kassem B.A. University of Cincinnati, 1991 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Professor Laura Jenkins i ABSTRACT: Eric Hobsbawm argues that recently created nations in the Middle East, such as Israel or Jordan, must be novel. In most instances, these new nations and nationalism that goes along with them have been constructed through what Hobsbawm refers to as “invented traditions.” This thesis will build on Hobsbawm’s concept of “invented traditions,” as well as add one additional but essential national building tool especially in the Middle East, which is the military tradition. These traditions are used by the state of Israel to create a sense of shared identity. These “invented traditions” not only worked to cement together an Israeli Jewish sense of identity, they were also utilized to create a sub national identity for the Druze. The state of Israel, with the cooperation of the Druze elites, has attempted, with some success, to construct through its policies an ethnic identity for the Druze separate from their Arab identity. -

2009/10- Accelerated Learning for Matriculation

Ministry of Education Directorate of the Southern, Northern and Haifa Districts, Directorate of Education, "Homesh" Program in the Bedouin sector, Directorate of Education in the Druze sector Success rate in the matriculation exams in the "obstacle" subject, within the program participants in 2009/10, among all students who began the program1 Tafnit Program for Matriculation‐ "Last Hurdle" Final Report 2009/10 Through the Accelerated Narrowing of Gaps Method (“The Study Campaign”)2; Success rates in the matriculation exams within the program, and additional data Report of activities in 44 high schools in 28 peripheral localities, with 1,270 participants, who according to their school assessment, prior to the program, will fail the matriculation exam in a particular subject ("obstacle subject"), that remains their "Last Hurdle" to a matriculation certificate. The activity was operated by the teaching staff from the participating schools. Tafnit Program for Matriculation‐ "Last Hurdle" Under the Academic Accreditation of the School of Education at Tel Aviv University The data in this report were provided by the participating schools and the statistical analysis is based on them. All data and analysis in this report were examined and approved by a team of the School of Education at Tel Aviv University In partnership with: • The Ministry of Education – Directorate of the Southern, Northern, Haifa Districts, Directorate of Education in the Bedouin sector, Directorate of Education in the Druze sector •Amal Network •Amit Network •Rosalinde & -

Amhayam Article V6a

AM HAYAM IN ISRAEL (or, On the Bus with Erez) by Diana Landau Cast of characters: UNTIL A FEW WEEKS AGO, most of us probably took for granted that Erez Pinhas (Abbago Travel) (funds permitting) we can fly all over the world to explore the past and present of alluring, far-off places. I can’t think of anywhere in the world Steve Berrick & Cindy Fox we could have had a richer travel experience than on our recent Israel Jane Dorval trip — so many thanks to Erez and the Am HaYam leaders (especially Yvonne Gunzburger Renate) who made it happen. And I hope I never again take for granted Judy Keller the privilege of being free to travel. Rebecca King Diana Landau (your reporter) Sunday afternoon, February 23. When Greg steered our car into Jane Dorval’s Eastham driveway—filled with luggage, travelers, and loved Lauren McCloud (Renate’s daughter) ones—it got real. Through a convoluted web of circumstances and more Kathy Shorr than one mitzvah, I was on my way to the Land of Israel with a lively, Carolyn & Len Solomon voluble, lovable group of Cape Codders from Am HaYam. Plus a huge Renate Wasserman bonus, girlpal Kathy Shorr as roommate. Paul Nimans (GalilEat) At the end of a smooth ride to Logan with Jane, daughter Becky, and Driver Dan, we found a clutch of other AH’ers at the El Al bag drop, where we were grilled mercilessly by cute, apparently teenage security “I was amazed by the changes since I personnel. Judy Keller, bless her, shepherded eight of us into the Air went to Israel in 1990. -

Israel Druze

Druze - Minority Rights Group https://minorityrights.org/minorities/druze/ Profile There are now more than 138,000 Druze located in eighteen villages, some exclusively Druze, others mixed, in the Galilee and Mt. Carmel in the occupied Golan Heights. Druze are ethnically Arab and Arabic speaking, but many do not consider themselves Palestinian. Their monotheistic religion incorporates many beliefs from Islam, Judaism and Christianity, and is also influenced by Greek philosophy and Hinduism. Druze have not proselytized since the 11th century, and the religion remains closed to outsiders. Historical context The Druze religion developed in the Middle Ages, and the first Druze settled in what is today southern Lebanon and northern Israel. The community enjoyed semi- autonomy during the Ottoman Empire and in 1921 France tried and failed to establish a Druze state within the French Mandate of Syria. Druze have traditionally adopted a practice of cooperating with national authorities, and Druze fought voluntarily alongside Jews in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war that accompanied Israel’s birth. Israeli authorities were able to exploit differences between Druze and Palestinians. In 1956 Druze were included in military conscription and were allowed to establish Druze religious courts in 1961. In 1970 special government departments were established solely for Druze. None of this protected them from the land confiscations and discriminatory budgets suffered by Palestinians, though not on quite the same scale. Within the Israeli military, Druze have played a key role in operations within the occupied territories due to their Arabic language skills. However, continuing discrimination against Druze and growing sympathy with Palestinians in the occupied territories has led some to question the community’s strategy of cooperation with the state.