INSTITUTE of JERUSALEM STUDIES JERUSALEM of INSTITUTE Autumn 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2010 - 2012 Volume VII

BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights is an independent, community-based non- This edition of the Survey of Palestinian Survey of Palestinian Refugees and profit organization mandated to defend Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons BADIL Internally Displaced Persons 2010-2012 and promote the rights of Palestinian (Volume VII) focuses on Palestinian Vol VII 2010-2012 refugees and Internally Displaced Persons Survey of refugees and IDPs. Our vision, mission, 124 Pages, 30 c.m. (IDPs) in the period between 2010 and ISSN: 1728-1679 programs and relationships are defined 2012. Statistical data and estimates of the by our Palestinian identity and the size of this population have been updated Palestinian Refugees principles of international law, in in accordance with figures as of the end Editor: Nidal al-Azza particular international human rights of 2011. This edition includes for the first law. We seek to advance the individual time an opinion poll surveying Palestinian Editorial Team: Amjad Alqasis, Simon and collective rights of the Palestinian refugees regarding specific humanitarian and Randles, Manar Makhoul, Thayer Hastings, services they receive in the refugee Noura Erakat people on this basis. camps. Demographic Statistics: Mustafa Khawaja BADIL Resource Center was established The need to overview and contextualize in January 1998. BADIL is registered Palestinian refugees and (IDPs) - 64 Internally Displaced Persons Layout & Design: Atallah Salem with the Palestinan Authority and years since the Palestinian Nakba Printing: Al-Ayyam Printing, Press, (Catastrophe) and 45 years since Israel’s legally owned by the refugee community Publishing and Distribution Conmpany represented by a General Assembly belligerent occupation of the West Bank, including eastern Jerusalem, and the 2010 - 2012 composed of activists in Palestinian Gaza Strip - is derived from the necessity national institutions and refugee to set the foundations for a human rights- community organizations. -

Fortid0308 Komplett.Indd

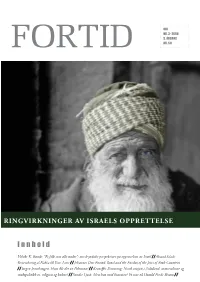

UIO NR. 3- 2008 5. ÅRGANG KR. 50 RINGVIRKNINGER AV ISRAELS OPPRETTELSE Innhold Vibeke K. Banik: ”Et folk som alle andre”: norsk-jødiske perspektiver på opprettelsen av Israel / / Ahmad Sa’adi: Remembering al-Nakba 60 Years Later / / Johannes Due Enstad: Israel and the Exodus of the Jews of Arab Countries / / Jørgen Jensehaugen: Hvor ble det av Palestina? / / Kristoffer Dannevig: Norsk misjon i Zululand: materialisme og maktpolitikk vs. religion og kultur? / / Sondre Ljoså: Men hva med historien? Et svar til Harald Frode Skram / / ISSN: 1504-1913 TRYKKERI: Allkopi REDAKTØR: Johannes Due Enstad og Anette Wilhelmsen REDAKSJONEN: Kristian Hunskaar, Martin Austnes, Mari Salberg, Øystein Idsø Viken, Stig Hosteland, Maria Halle, Olav Bogen, Marie Lund Alveberg, Marthe Glad Munch-Møller, Tor Gunnar Jensen og Steinar Skjeggedal ILLUSTRASJON OG GRAFISK UTFORMING: Forsideillustrasjon: Arabisk jøde fra Yemen. Mellom 1898 og 1914. Fotograf: American Colony (Jerusalem), Photo dept. Fotografi et er en del av G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, og er fritt tilgjengelig via commons.wikimedia.org. NB! Utsnitt. Svart/hvitt-fotografi et er delvis fargelagt. Forsidelayout og sidetegning: Alexander Worren (cover) og Trine Suphammer (sidetegning). KONTAKTTELEFON: 971 37 554 (Johannes Due Enstad) og 481 99 592 (Anette Wilhelmsen) E-POST: [email protected] NETTSIDE: www.fortid.no KONTAKTADRESSE: Universitetet i Oslo, IAKH, Fortid, Pb. 1008 Blindern, 0315 Oslo Fortid er medlem av tidsskriftforeningen, se www.tidsskriftforeningen.no Fortid utgis med støtte fra Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie ved Universitetet i Oslo, SiO og Norsk kulturråd Innholdsfortegnelse Fortid nr. 3 - 2008 5 LEDER 7 KORTTEKSTER ARTIKLER 12 ”Et folk som alle andre”: norsk-jødiske perspektiver på opprettelsen av Israel Vibeke K. -

By Celeste Gianni History of Libraries in the Islamic World: a Visual Guide

History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide by Celeste Gianni History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide by Celeste Gianni Published by Gimiano Editore Via Giannone, 14, Fano (PU) 61032 ©Gimiano Editore, 2016 All rights reserved. Printed in Italy by T41 B, Pesaro (PU) First published in 2016 Publication Data Gianni, Celeste History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide ISBN 978 88 941111 1 8 CONTENTS Preface 7 Introduction 9 Map 1: The First Four Caliphs (10/632 - 40/661) & the Umayyad Caliphate (40/661 - 132/750) 18 Map 2: The ʿAbbasid Caliphate (132/750 - 656/1258) 20 Map 3: Islamic Spain & North African dynasties 24 Map 4: The Samanids (204/819 - 389/999), the Ghaznavids (366/977 - 558/1163) and the Safavids (906/1501 - 1148/1736) 28 Map 5: The Buyids (378/988 - 403/1012) 30 Map 6: The Seljuks (429/1037 - 590/1194) 32 Map 7: The Fatimids (296/909 - 566/1171) 36 Map 8: The Ayyubids (566/1171 - 658/1260) 38 Map 9: The Mamluks (470/1077 - 923/1517) 42 Map 10: After the Mongol Invasion 8th-9th/14th - 15th centuries 46 Map 11: The Mogul Empire (932/1526 - 1273/1857) 48 Map 12: The Ottoman Empire (698/1299 - 1341/1923) up to the 12th/18th century. 50 Map 13: The Ottoman Empire (698/1299 - 1341/1923) from 12th/18th to the 14th/20th century. 54 Bibliography 58 PREFACE This publication is very much a basic tool intended to help different types of libraries by date, each linked to a reference so that researchers working in the field of library studies, and in particular the it would be easier to get to the right source for more details on that history of library development in the Islamic world or in comparative library or institution. -

Scholars, Chroniclers, and Jerusalem Archivists

Palestine in the Nineteenth Century Library (no. 963 in the catalogue) sources, and its members may be written by a certain Muhammad put forth confidently as the direct Scholars, Chroniclers, ibn `Abd al-Rahman ibn `Abd ancestors of the modern family. al-`Aziz al-Khalidi who, as we can The series begins with Shams deduce from internal evidence, lived al-Din Muhammad ibn `Abdullah in the mid-eleventh century, and al-`Absi al-Dayri al-Maqdisi who and Jerusalem most probably before the Crusader was born in Jerusalem around 1343 occupation of the city in 1099. We and died there on November 2, know that this occupation caused 1424. His father was a merchant, a mass exodus from Jerusalem, originally from a Nablus district Archivists scattering its families in all called al-Dayr. Encouraged by directions. A family tradition has it his father, Muhammad studied in A History of the Khalidis that the Khalidis sought refuge in Jerusalem, Damascus, and Cairo the village of Dayr `Uthman, in the and then became a Hanafite mufti province of Nablus and returned to of Jerusalem and a distinguished Jerusalem after Saladin recaptured scholar and teacher. the city on October 2, 1187. When Two of Muhammad’s five sons they came back, they were known achieved the same renown as as Dayris or Dayri/Khalidis, but this their father: Sa`d al-Din Sa`d who remains a mere possibility because it was born in Jerusalem in 1367 is unattested in the sources. he history of families is a and died in Cairo in 1463 and notoriously difficult subject. -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Route 181 Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel a Film by Michel Khleifi & Eyal Sivan

Momento!, Sourat Films & Sindibad Films present Route 181 Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel A film by Michel Khleifi & Eyal Sivan English-language Press-pack (Digital photographs will be provided on request) Contact Information: Sindibad Films Limited, 5 Princes Gate, London SW7 1QJ, UK Tel: + 44 207 823 74 88, Fax: + 44 207 823 91 37 Email: [email protected] , http://www.sindibad.co.uk Or Momento! email: [email protected] Tel + 33 1 43 66 25 24 Fax + 33 1 43 66 86 00 http://www.momento-productions.com Momento!, Sourat Films & Sindibad Films present Route 181 – Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel A film by Michel KHLEIFI & Eyal SIVAN Route 181 offers an unusual vision of the inhabitants of Palestine-Israel, a common vision of a Palestinian and an Israeli. For more than a year now, Khleifi and Sivan have dedicated themselves to producing what they consider a cinematic act of faith: a film co-directed by a Palestinian and by an Israeli. In the summer of 2002, for two long months, they travelled together from the south to the north of their country of birth, traced their trajectory on a map and called it Route 181. This virtual line follows the borders outlined in Resolution 181, which was adopted by the United Nations on November 29th 1947 to partition Palestine into two states. As they travel along this route, they meet women and men, Israeli and Palestinian, young and old, civilians and soldiers, filming them in their everyday lives. Each of these characters has their own way of evoking the frontiers that separate them from their neighbours: concrete, barbed-wire, cynicism, humour, indifference, suspicion, aggression…Frontiers have been built on the hills and in the plains, on mountains and in valleys but above all inside the minds and souls of these two peoples and in the collective unconscious of both societies. -

The Israel/Palestine Question

THE ISRAEL/PALESTINE QUESTION The Israel/Palestine Question assimilates diverse interpretations of the origins of the Middle East conflict with emphasis on the fight for Palestine and its religious and political roots. Drawing largely on scholarly debates in Israel during the last two decades, which have become known as ‘historical revisionism’, the collection presents the most recent developments in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict and a critical reassessment of Israel’s past. The volume commences with an overview of Palestinian history and the origins of modern Palestine, and includes essays on the early Zionist settlement, Mandatory Palestine, the 1948 war, international influences on the conflict and the Intifada. Ilan Pappé is Professor at Haifa University, Israel. His previous books include Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (1988), The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–51 (1994) and A History of Modern Palestine and Israel (forthcoming). Rewriting Histories focuses on historical themes where standard conclusions are facing a major challenge. Each book presents 8 to 10 papers (edited and annotated where necessary) at the forefront of current research and interpretation, offering students an accessible way to engage with contemporary debates. Series editor Jack R.Censer is Professor of History at George Mason University. REWRITING HISTORIES Series editor: Jack R.Censer Already published THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND WORK IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE Edited by Lenard R.Berlanstein SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE -

Documentation of Statistics in the “Israel-Palestine Scorecard”

Documentation of Statistics in the “Israel-Palestine Scorecard” 1. Population Displacement The 1967 Palestinian exodus refers to the flight of around 280,000 to 325,000 Palestinians[a] out of the territories taken by Israel during and in the aftermath of the Six-Day War, including the demolition of the Palestinian villages of Imwas, Yalo, and Bayt Nuba, Surit, Beit Awwa, Beit Mirsem, Shuyukh, Al-Jiftlik, Agarith and Huseirat and the "emptying" of the refugee camps of Aqabat Jaber and ʿEin as-Sultan.[b] aBowker, Robert P. G. (2003). Palestinian Refugees: Mythology, Identity, and the Search for Peace. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1-58826-202-2 bGerson, Allan (1978). Israel, the West Bank and International Law. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-3091-8 cUN Doc A/8389 of 5 October 1971. Para 57. appearing in the Sunday Times (London) on 11 October 1970 2. Palestinian Land Annexed, Expropriated, or totally controlled by Israel Palestinian Loss of Land: 1967 - 2014 Since the 1993 Oslo Accords, the Palestinian Authority officially controls a geographically non-contiguous territory comprising approximately 11% of the West Bank (known as Area A) which remains subject to Israeli incursions. Area B (approx. 28%) is subject to joint Israeli-Palestinian military and Palestinian civil control. Area C (approx. 61%) is under full Israeli control. According to B'tselem, the vast majority of the Palestinian population lives in areas A and B and less than 1% of area C is designated for use by Palestinians, who are also unable to legally build in their own existing villages in area C due to Israeli authorities' restrictions. -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

Israel: Timeless Wonders

Exclusive U-M Alumni Travel departure – October 9-20, 2021 Israel: Timeless Wonders 12 days for $6,784 total price from Detroit ($5,995 air & land inclusive plus $789 airline taxes and fees) Encounter a land of extraordinary beauty and belief, of spirit and story, history and hospitality. From modern Tel Aviv to scenic Upper Galilee, ancient Tiberias and storied Nazareth to Jeru- salem, “City of Gold,” we engage all our senses in a small group encounter with this extraordinary and holy land, with a five-night stay in Jerusalem at the legendary King David hotel. Upper Destination Galilee Motorcoach Extension (motorcoach) Tiberias Entry/Departure Amman Tel Aviv JORDAN Mediterranean Jerusalem Sea Dead Sea ISRAEL Petra We enjoy guided touring and ample time to explore on our own in Jerusalem, one of the world's oldest and most treasured cities. Avg. High (°F) Oct Nov Day 1: Depart U.S. for Tel Aviv, Israel Day 5: Mount Bental/Tiberias Today begins with Tiberias 86 75 Jerusalem 81 70 a special tour of the kibbutz, followed by a visit to a Day 2: Arrive Tel Aviv We arrive today and transfer local winery. We continue on to Mount Bental in to our hotel. As guests’ arrival times may vary greatly, the Golan Heights for a panoramic view of Israel, we have no group activities or meals planned and are Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan. Next: the ruins of Your Small Group Tour Highlights at leisure to explore or relax as we wish. Capernaum, where Jesus taught in the synagogue on the Sabbath; Tabgha, site of the Miracle of the Loaves Tel Aviv touring, including “White City” of Bauhaus archi- Day 3: Tel Aviv Today we encounter the vibrant and Fishes; and Kibbutz Ginosar, where we see the tecture • Jaffa’s ancient port • Artists’ village of Ein Hod modern city of Tel Aviv, Israel’s arts and culture “Jesus Boat” carbon dated to 100 BCE. -

Rights in Principle – Rights in Practice, Revisiting the Role of International Law in Crafting Durable Solutions

Rights in Principle - Rights in Practice Revisiting the Role of International Law in Crafting Durable Solutions for Palestinian Refugees Terry Rempel, Editor BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights, Bethlehem RIGHTS IN PRINCIPLE - RIGHTS IN PRACTICE REVISITING THE ROLE OF InternatiONAL LAW IN CRAFTING DURABLE SOLUTIONS FOR PALESTINIAN REFUGEES Editor: Terry Rempel xiv 482 pages. 24 cm ISBN 978-9950-339-23-1 1- Palestinian Refugees 2– Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons 3- International Law 4– Land and Property Restitution 5- International Protection 6- Rights Based Approach 7- Peace Making 8- Public Participation HV640.5.P36R53 2009 Cover Photo: Snapshots from «Go and See Visits», South Africa, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cyprus and Palestine (© BADIL) Copy edit: Venetia Rainey Design: BADIL Printing: Safad Advertising All rights reserved © BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights December 2009 P.O. Box 728 Bethlehem, Palestine Tel/Fax: +970 - 2 - 274 - 7346 Tel: +970 - 2 - 277 - 7086 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.badil.org iii CONTENTS Abbreviations ....................................................................................vii Contributors ......................................................................................ix Foreword ..........................................................................................xi Foreword .........................................................................................xiv Introduction ......................................................................................1