This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Celeste Gianni History of Libraries in the Islamic World: a Visual Guide

History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide by Celeste Gianni History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide by Celeste Gianni Published by Gimiano Editore Via Giannone, 14, Fano (PU) 61032 ©Gimiano Editore, 2016 All rights reserved. Printed in Italy by T41 B, Pesaro (PU) First published in 2016 Publication Data Gianni, Celeste History of Libraries in the Islamic World: A Visual Guide ISBN 978 88 941111 1 8 CONTENTS Preface 7 Introduction 9 Map 1: The First Four Caliphs (10/632 - 40/661) & the Umayyad Caliphate (40/661 - 132/750) 18 Map 2: The ʿAbbasid Caliphate (132/750 - 656/1258) 20 Map 3: Islamic Spain & North African dynasties 24 Map 4: The Samanids (204/819 - 389/999), the Ghaznavids (366/977 - 558/1163) and the Safavids (906/1501 - 1148/1736) 28 Map 5: The Buyids (378/988 - 403/1012) 30 Map 6: The Seljuks (429/1037 - 590/1194) 32 Map 7: The Fatimids (296/909 - 566/1171) 36 Map 8: The Ayyubids (566/1171 - 658/1260) 38 Map 9: The Mamluks (470/1077 - 923/1517) 42 Map 10: After the Mongol Invasion 8th-9th/14th - 15th centuries 46 Map 11: The Mogul Empire (932/1526 - 1273/1857) 48 Map 12: The Ottoman Empire (698/1299 - 1341/1923) up to the 12th/18th century. 50 Map 13: The Ottoman Empire (698/1299 - 1341/1923) from 12th/18th to the 14th/20th century. 54 Bibliography 58 PREFACE This publication is very much a basic tool intended to help different types of libraries by date, each linked to a reference so that researchers working in the field of library studies, and in particular the it would be easier to get to the right source for more details on that history of library development in the Islamic world or in comparative library or institution. -

Jordan – Palestinians – West Bank – Passports – Citizenship – Fatah

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: JOR35401 Country: Jordan Date: 27 October 2009 Keywords: Jordan – Palestinians – West Bank – Passports – Citizenship – Fatah This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide background on the issue of Jordanian citizenship for persons of West Bank Palestinian descent. 2. What is the overall situation for Palestinian citizens of Jordan? 3. Have there been any crackdowns upon Fatah members over the last 15 years? 4. What kind of relationship exists between Fatah and the Jordanian authorities? RESPONSE 1. Please provide background on the issue of Jordanian citizenship for persons of West Bank Palestinian descent. Most Palestinians in Jordan hold a Jordanian passport of some type but the status accorded different categories of Palestinians in Jordan varies, as does the manner and terminology through which different sources classify and discuss Palestinians in Jordan. The webpage of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) states that: “All Palestine refugees in Jordan have full Jordanian citizenship with the exception of about 120,000 refugees originally from the Gaza Strip, which up to 1967 was administered by Egypt”; the latter being “eligible for temporary Jordanian passports, which do not entitle them to full citizenship rights such as the right to vote and employment with the government”. -

Scholars, Chroniclers, and Jerusalem Archivists

Palestine in the Nineteenth Century Library (no. 963 in the catalogue) sources, and its members may be written by a certain Muhammad put forth confidently as the direct Scholars, Chroniclers, ibn `Abd al-Rahman ibn `Abd ancestors of the modern family. al-`Aziz al-Khalidi who, as we can The series begins with Shams deduce from internal evidence, lived al-Din Muhammad ibn `Abdullah in the mid-eleventh century, and al-`Absi al-Dayri al-Maqdisi who and Jerusalem most probably before the Crusader was born in Jerusalem around 1343 occupation of the city in 1099. We and died there on November 2, know that this occupation caused 1424. His father was a merchant, a mass exodus from Jerusalem, originally from a Nablus district Archivists scattering its families in all called al-Dayr. Encouraged by directions. A family tradition has it his father, Muhammad studied in A History of the Khalidis that the Khalidis sought refuge in Jerusalem, Damascus, and Cairo the village of Dayr `Uthman, in the and then became a Hanafite mufti province of Nablus and returned to of Jerusalem and a distinguished Jerusalem after Saladin recaptured scholar and teacher. the city on October 2, 1187. When Two of Muhammad’s five sons they came back, they were known achieved the same renown as as Dayris or Dayri/Khalidis, but this their father: Sa`d al-Din Sa`d who remains a mere possibility because it was born in Jerusalem in 1367 is unattested in the sources. he history of families is a and died in Cairo in 1463 and notoriously difficult subject. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Protestant Missions, Seminaries and the Academic Study of Islam in the United States A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies by Caleb D. McCarthy Committee in charge: Professor Juan E. Campo, Chair Professor Kathleen M. Moore Professor Ann Taves June 2018 The dissertation of Caleb D. McCarthy is approved. _____________________________________________ Kathleen M. Moore _____________________________________________ Ann Taves _____________________________________________ Juan E. Campo, Committee Chair June 2018 Protestant Missions, Seminaries and the Academic Study of Islam in the United States Copyright © 2018 by Caleb D. McCarthy iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While the production of a dissertation is commonly idealized as a solitary act of scholarly virtuosity, the reality might be better expressed with slight emendation to the oft- quoted proverb, “it takes a village to write a dissertation.” This particular dissertation at least exists only in light of the significant support I have received over the years. To my dissertation committee Ann Taves, Kathleen Moore and, especially, advisor Juan Campo, I extend my thanks for their productive advice and critique along the way. They are the most prominent among many faculty members who have encouraged my scholarly development. I am also indebted to the Council on Information and Library Research of the Andrew C. Mellon Foundation, which funded the bulk of my archival research – without their support this project would not have been possible. Likewise, I am grateful to the numerous librarians and archivists who guided me through their collections – in particular, UCSB’s retired Middle East librarian Meryle Gaston, and the Near East School of Theology in Beriut’s former librarian Christine Linder. -

ACOR Newsletter Vol. 12.2

ACOR Newsletter ^i ^ Vol. 12.2—Winter 2000 Qastal, 1998-2001 On a cold afternoon in early February 2000, Ra'ed Abu Ghazi, a management trainee for the Qastal Erin Addison Conservation and Development Project (QCDP), was walking home from the Umayyad qasr and mosque complex at Qastal (map, p. 9). In the lot between the ancient reservoir and his home, he stopped to speak to some neighbor children playing a game. Then a teapot overturned and the late afternoon sun re- flected off a blue-green, glassy surface. Ra'ed knelt to get a closer look and brushed gently at the loose earth. The area had recently been bulldozed, so the dirt was loose and only about five centimeters deep. As he washed the surface with tea water, a pattern of bril- liant glass tesserae was revealed. Ra'ed had made an exciting discovery at Qastal: a large structure from the late Umayyad period (A.D. 661-750), floored with what experts have called some of the most exquisite mosaics in Jordan (Figs. 1-3). The new structure is only the most recent development in two-and-a-half fascinating years at Qastal. Qastal al-Balqa' is men- tioned in the Diwan of Kuthayyir 'Azza (d. A.H. 105=A.o. 723): "God bless the houses of those living between Muwaqqar and Qastal al-Balqa', where the mihrabs are." Al- though there remain com- plex questions about this reference to "mihrabs" (maharib—apparently plural), the quote at least tells us that Qastal was well enough known to have served as a geo- graphical reference point before A.D. -

Till We Have Built Jerusalem: Reading Group Gold

FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX Reading Group Gold Till We Have Built Jerusalem: Architects of a New City by Adina Hoffman ISBN: 978-0-374-28910-2 / 368 pages A remarkable view of one of the world’s most beloved and troubled cities, Adina Hoffman’s Till We Have Built Jerusalem is a gripping and intimate journey into the very different lives of three archi- tects who helped shape modern Jerusalem. The book unfolds as an excavation. It opens with the 1934 arrival in Jerusalem of the celebrated Berlin architect Erich Mendelsohn, a refugee from Hitler’s Germany, who must reckon with a com- plex new Middle Eastern reality. Driven to build in terms both practical and prophetic, Mendelsohn is a maverick whose ideas about Jerusalem’s political and visual prospects place him on a collision course with his peers. Next we meet Austen St. Barbe Harrison, Palestine’s chief government ar- chitect from 1922 to 1937. Steeped in the traditions of Byzantine and Islamic building, this “most private of public servants” finds himself working under the often stifling and violent conditions of British rule. And in the riveting final section, Hoffman herself sets out through the battered streets of today’s Jerusalem searching for traces of a possibly Greek, possibly Arab architect named Spyro Houris. Once a fixture on the local scene, Houris is now utterly forgotten, though his grand, Arme- nian-tile-clad buildings still stand, a ghostly testimony to the cultural fluidity that has historically characterized Jerusalem at its best. We hope that the following discussion topics will enrich your reading group’s experience of this beautifully written rumination on memory and forgetting, place and displacement, and on what it means, everywhere, to be foreign and to belong. -

CHS Baseball Team Op Ens Season Tate's Best Track Girls Competing Here in Chelsea Relays

mmm WEATHER QUOTE Mln. Mux Preclp. Thursday, April 1? 43 61 0.02 "A few honest men are'better Friday, A[>rll i3 42 uo IMO than numbers, If you choose god Saturday. April 14 40 62 0.11 Sunday, April 15 40 47 Truce ly, honest men to be captains of Monday, April 16 34 54 u.fio horse, honest men will follow." Tuesday, April 1? U 57 j1.no , —Oliver Cromwell. Wednesday, April 18 40 63 0,00 • PI us 15c per copy ONE HUNDRED-NINTH YEAR—No. 45 16 Pages This Week 2 Supplements CHELSEA, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, APRIL 19, 1979 USPS 101-720 SUBSCRIPTION: $«.00 PER YEAR CHS Baseball tate's Best Track Team Girls Competing Here Open s season In Chelsea Relays » At long last the weatherman Roger Mo^re, John Dunn and Jefl cooperated ahd allowed the Chel Dils each contributed one hit to South.- School Twelve Strong Teams sea High school varsity baseball the effort. Three Bulldogs tied in the RBI's team to take the field and begin department, with Augustine, Moore this season. and Jeff Oils' each driving in two. Fun Fair Set Entered in Saturday Meet the Bulldogs took out their ear Lou Jahnke and John Dunn each ly season frustration on South; Ly brought home one. Some of the best track girls in jump team and Chelsea's pair of For Saturday the state will be in town this Sa Lorrie Vandegrift and Tracy Boh- on, soundly trouncing sthe Lions, Mike Eisele, the starting pitch 11-2, Tuesday afternoon at home. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

CHURCH and PEOPLE " Holyrussia," the Empire Is Called, and the Troops of The

CHAPTER V CHURCH AND PEOPLE " HOLYRussia," the Empire is called, and the troops of the Tsar are his " Christ-loving army." The slow train stops at a wayside station, and..among the grey cot- The Church. tages on the hillside rises a white church hardly supporting the weight of a heavy blue cupola. The train approaches a great city, and from behind factory chimneys cupolas loom up, and when the factory chimneys are passed it is the domes and belfries of the churches that dominate the city. " Set yourselves in the shadow of the sign of the Cross, O Russian folk of true believers," is the appeal that the Crown makes to the people at critical moments in its history. With these words began the Manifesto of Alexander I1 announcing the emancipation of the serfs. And these same words were used bfthose mutineers on the battleship Potenzkin who appeared before Odessa in 1905. The svrnbols of the Orthodox Church are set around Russian life like banners, like ancient watch- towers. The Church is an element in the national conscious- ness. It enters into the details of life, moulds custom, main- tains a traditional atmosphere to the influence of which a Russian, from the very fact that he is a Russian, involuntarily submits. A Russian may, and most Russian intelligents do, deny the Church in theory, but in taking his share in the collective life of the nation he, at many points, recognises the Ch'urch as a fact. More than that. In those borcler- lands of emotion that until life's end evade the control of toilsomely acquired personal conviction, the Church retains a foothold, yielding only slowly and in the course of generations to modern influences. -

Jewish Studies Fall 2020 Courses MODE of COURSE COURSE TITLE DISTRO INSTRUCTOR INSTRUCTION TIME Remote & MTWTH HEBREW 111-1-20 Hebrew I R

Jewish Studies Fall 2020 Courses MODE OF COURSE COURSE TITLE DISTRO INSTRUCTOR INSTRUCTION TIME Remote & MTWTH HEBREW 111-1-20 Hebrew I R. Alexander Synchronous 10:20 – 10:10 Remote & MTWTH HEBREW 121-1-20 Hebrew II H. Seltzer Synchronous 11:30 –12:20 HISTORY 300-0-22 Comparative IV S. Ionescu Remote & TTH 11:20 – 12:40 Genocide Synchronous HISTORY 348-1-20 Jews in Poland, IV Y. Petrovsky- Remote & TTH 2:40 – 4:00 Ukraine and Russia: Shtern Synchronous 1250 - 1917 JWSH_ST 101-6-1 A Rabbi and a Priest C. Sufrin Remote & TTH 1:00 – 2:20 (First-year seminar) walk into a bar… to talk about God Synchronous JWSH_ST 278-0-1 Tales of Love and VI M. Moseley Remote & MW 4:10 – 5:30 Darkness: Eros and Isolation in Modern Synchronous Hebrew Literature JWSH_ST 280-4-1 (Hybrid) Arabs and Jews in Hybrid or Remote & TTH 1:00 – 2:20 Palestine/The Land IV M. Hilel JWSH_ST 280-4-2 (Remote) Synchronous (also HISTORY 200-0-22/22B) of Israel, 1880-1948 JWSH_ST 280-5-1 Zionism and its Critics V S. Hirschhorn Remote & TTH 4:20 – 5:40 Synchronous JWSH_ST 390-0-1 Jewishness in R. Moss Remote & TTH 9:40 – 11:00 (also THEATRE 240-0-20) Performance Synchronous RELIGION 220-0-20 Introduction to V B. Wimpfheimer Remote & MW 9:40 – 11:00 Hebrew Bible Synchronous RELIGION 339-0-20 Gender and Sexuality V C. Sufrin Remote & TTH 9:40 – 11:00 (also GNDR_ST 390-0-21) in Judaism Synchronous What is Jewish Studies? Jewish Studies refers to the study of Judaism, Jewish history, Jewish identity and Jewish culture over time and around the world. -

Albert Hourani (1915-1993)

Int. J. Middle East Stud. 25 (1993), i-iv. Printed in the United States of America Leila Fawaz IN MEMORIAM: ALBERT HOURANI (1915-1993) With the death of Albert Hourani, IJMES has lost far more than a member of its Editorial Board. It has lost an inspiration, an calim, and a friend. From the time he joined the board in 1990, he served IJMES with the same dedication he gave to all his responsibilities. He was interested in the journal and followed its progress closely. His evaluations, typed on his notorious manual typewriter with faded ribbons, always came by return mail, for he broke all records when it came to reliability. Invariably, these carried the unmistakable Hourani stamp: unique combinations of measured tone and gentle understatement, forceful intellect, and masterly erudition. No one else combined generosity and kindness with such un- faltering intellectual excellence in quite the same way or to quite the same extent. He loved to read the works of promising young scholars, and he supported their writings even if they criticized his. He was the greatest critic of his own works; yet he gave others every break he could and offered detailed and thorough com- ments on how to improve their work. As John Spagnolo, in a collectively written appreciation that introduces Problems of the Modern Middle East in Historical Perspective: Essays in Honor of Albert Hourani (1992), wrote: Typically, he would begin with an encouraging "I read your chapter with enormous inter- est." Then, after some appreciative reflection, he would, with enlightening clarity, spell out the latent significance of the work in question: "thinking about your thesis, I can now dis- cern a general thread running through it ..." Finally, after tactfully suggesting the need for "a few small corrections," there followed several pages of carefully thought out and pains- takingly annotated comments. -

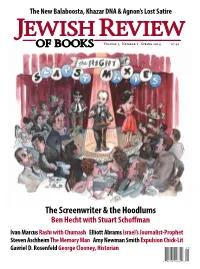

JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95

The New Balaboosta, Khazar DNA & Agnon’s Lost Satire JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95 The Screenwriter & the Hoodlums Ben Hecht with Stuart Schoffman Ivan Marcus Rashi with Chumash Elliott Abrams Israel’s Journalist-Prophet Steven Aschheim The Memory Man Amy Newman Smith Expulsion Chick-Lit Gavriel D. Rosenfeld George Clooney, Historian NEW AT THE Editor CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Associate Editor Amy Newman Smith Administrative Assistant Rebecca Weiss Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Publisher Eric Cohen Associate Publisher & Director of Marketing Lori Dorr NEW SPACE The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, The David Berg Rare Book Room is a state-of- Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication the-art exhibition space preserving and dis- of ideas and criticism published in Spring, Summer, playing the written word, illuminating Jewish Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 165 East 56th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022. history over time and place. For all subscriptions, please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or send $29.95 UPCOMING EXHIBITION ($39.95 outside of the U.S.) to Jewish Review of Books, Opening Sunday, March 16: By Dawn’s Early PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Please send notifi- cations of address changes to the same address or to Light: From Subjects to Citizens (presented by the [email protected].