ACCOUNTABILITY and INCENTIVES of APPOINTED and ELECTED PUBLIC OFFICIALS Zohal Hessami*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kreisverwaltung

Info Kreisverwaltung 1 Vogelsbergkreis – Der Kreisausschuss – Goldhelg 20 – 36341 Lauterbach/Hessen Telefon: 06641 977-0 – Fax 977-336 – [email protected] – Ausgabe 2009 www.vogelsbergkreis.de vermeiden – verwerten – entsorgen Dienstleistungsfirma ZAV Wir sind für Sie da… und wohin mit dem …wenn es um die umwelt- abfall? gerechte Abfall-Entsorgung geht. Bevor wir uns fragen, wohin mit dem Abfall, müssen wir uns eigentlich fragen, woher kommt denn der Abfall? Mit ca. 150 kg bis 350 kg Abfällen pro Einwohner im Jahr trägt der Verbrau- cher ganz wesentlich zum Müllberg bei. Letztendlich entschei- det jeder Einzelne von uns durch sein Kaufverhalten über die Abfallproduktion. Die Müllsortierung ist ein wichtiger Schritt, um Rohstoffe zu sparen, doch wer es mit dem Umweltschutz ernst nimmt, darf den Müll gar nicht erst entstehen lassen. Regie- rung, Produzenten und Verbraucher sind gleichermaßen aufge- fordert, zu einer nachhaltigen Wirtschaftsweise beizutragen. Verbraucher unterschätzen oftmals ihren Einfluß auf den Markt. Produkte, die nicht gekauft werden, werden bald nicht mehr haben Sie fragen zum abfall hergestellt. Überlegen Sie deshalb bei jedem Einkauf: Brauche ich dieses Produkt überhaupt? Kann ich auf eine Alternative und zur entsorgung im ausweichen, die umweltfreundlicher und abfallärmer ist? Gibt vogelsbergkreis? es ein vergleichbares Produkt, das länger hält, sich besser reparieren oder wiederverwenden läßt? wir sind für sie da! Versuchen Sie, bewusst Abfall zu vermeiden, indem Sie die Ver- meidungsangebote wie Mehrweg-, Nachfüllprodukte und recy- celbare Verpackungen aus Glas, Metall und Papier bevorzugen. Was Sie darüber hinaus aber noch tun können und wie Sie unvermeidbare Abfälle richtig entsorgen, erfahren Sie aus dem eselswörth 23 Abfallratgeber des Zweckverbandes Abfallwirtschaft Vogels- bergkreis (ZAV). -

Interkommunale Kooperationen: Interkommunale Kooperation Stadt-Land-Schloss (Alsfeld, Antrifttal, Romrod)

Interkommunale Kooperationen: Interkommunale Kooperation Stadt-Land-Schloss (Alsfeld, Antrifttal, Romrod) - Alsfeld - Kernstadt - Antrifttal - Ruhlkirchen Romrod - Kernstadt; Bahnhof Romrod - Zell Kommunale Arbeitsgemeinschaft Hessisches Kegelspiel (Burghaun, Hünfeld, Nüsttal, Rasdorf) - Burghaun - Ortskern; Sport- Freizeitanlage Am Weiher Hünfeld - Bahnbereich; Innenstadt Hünfeld - Rasdorf - Ortskern; Sport- und Freizeitanlage Interkommunale Kooperation Hinterland - Bad Laaspe (Angelburg, Bad Endbach, Biedenkopf, Breidenbach, Dautphetal, Gladenbach, Lohra, Steffenberg) - Angelburg - Frechenhausen - Bad Endbach - Verbindung Bad Endbach – Hartenrod - Biedenkopf - Altstadt - Breidenbach - Ortsmitte - Dautphetal - Ortsmitte Dautphe - Gladenbach - Innenstadtinsel - Lohra - Ortsmitte - Steffenberg - Gewerbegebiet Niedereisenhausen Interkommunale Kooperation Bergstraße (Bensheim, Einhausen, Heppenheim, Lautertal (Odenwald), Lorsch, Zwingenberg) - Bensheim - Bensheim Südwest; Westliche Innenstadt - Einhausen - Ortszentrum - Heppenheim - An der Innenstadt Heppenheim - Lautertal - Felsenmeer Reichenbach; Ortsmitte Reichenbach in Lautertal - Lorsch - Stadt- und Kulturzentrum - Zwingenberg - Rund um die historische Markthalle Interkommunale Kooperation Schwalm-Eder-Mitte (Homberg (Efze), Knüllwald, Schwarzenborn) - Homberg (Efze) - Altstadt um den Marktplatz; Stadtteil Mühlhausen - Knüllwald - Remsfeld (in den Bereichen Stuhlfabrik, innerörtliche Siedlungsfläche mit dem entwidmeten Gebäude/ Grundstück der katholischen Kirche); Niederbeisheim (mit -

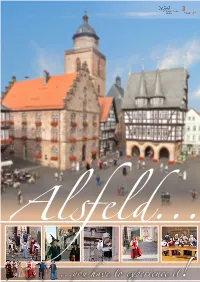

You Have to Experience

Alsfeld... ...you have to experience it! Bücking House on the Market Place (1893) Market Place with Wine House and Town Hall (1878) South side of the Market Place (approx.. 1870) If walls and arches could speak, they would tell the visitor many tales about the history of Alsfeld… Originally called “Adelesfelt”, Alsfeld was founded in 8th - 9th century as the seat of the Carolingian Court. It was first documented in 1069. In 1605, the Chronicles of “Hessica von Dillich” describe Alsfeld as a distinguished place and as the capital city of Hesse. This was due to the favourable geographical position on the trade routes leading from Frankfurt to Thuringia, thus cementing Alsfeld’s importance. Alsfeld had its own royal mint, market privileges and in 1222 acquired city status. 2 HistoricalA living reflection of history Tradition welcomes the future 3 European model city for heritage building Attractionsconservation. The famous Market Place Trio of the Town Hall, The Wedding House, The Stumpf House The Walpurgis Church, the main parish the Wine House and No.2 Market Place and The Bücking House church of Alsfeld Welcome to a town where the wood timbered architecture is a feast for your eyes! In 1878 the town councillors wanted to have the Town Hall pulled down. Luckily their plans were stopped. Since then no such thoughts have been entertained. On the contrary: preserve, maintain and renovate has become the motto of Alsfeld. The results were so exemplary and convincing that in 1975, the European Council selected Alsfeld as a European Model Town. An exciting excursion back in time is to walk through the town with its over 400 half-timbered buildings, spanning 700 years of history. -

Ergebnisse Landwirtschaft VB 2018.Xlsx

Bodenrichtwert Grünland Bodenrichtwert Ackerland Gemeinde Gemarkung Stichtag: 01.01.2018 Stichtag: 01.01.2018 Alsfeld Alsfeld 1,00 € 1,40 € Alsfeld Altenburg 1,00 € 1,40 € Alsfeld Angenrod 1,00 € 1,10 € Alsfeld Berfa 0,80 € 1,00 € Alsfeld Billertshausen 1,00 € 1,20 € Alsfeld Eifa 0,90 € 1,40 € Alsfeld Elbenrod 0,90 € 1,10 € Alsfeld Eudorf 1,40 € 1,70 € Alsfeld Fischbach 0,90 € 1,30 € Alsfeld Hattendorf 1,10 € 1,40 € Alsfeld Heidelbach 1,10 € 1,40 € Alsfeld Leusel 1,00 € 1,10 € Alsfeld Liederbach 1,00 € 1,40 € Alsfeld Lingelbach 0,90 € 1,40 € Alsfeld Münch-Leusel 1,10 € 1,40 € Alsfeld Reibertenrod 1,00 € 1,30 € Alsfeld Schwabenrod 1,20 € 1,40 € Antrifttal Bernsburg 0,90 € 1,10 € Antrifttal Ohmes 0,80 € 0,90 € Antrifttal Ruhlkirchen 0,75 € 1,10 € Antrifttal Seibelsdorf 0,70 € 1,20 € Antrifttal Vockenrod 0,80 € 1,30 € Feldatal Ermenrod 0,45 € 0,50 € Feldatal Groß-Felda 0,55 € 0,70 € Feldatal Kestrich 0,55 € 0,60 € Feldatal Köddingen 0,45 € 0,50 € Feldatal Stumpertenrod 0,40 € 0,55 € Feldatal Windhausen 0,40 € 0,50 € Feldatal Zeilbach 0,50 € 0,55 € Freiensteinau Fleschenbach 0,70 € 0,75 € Freiensteinau Freiensteinau 0,45 € 0,45 € Freiensteinau Gunzenau 0,50 € 0,50 € Freiensteinau Holzmühl 0,40 € 0,50 € Freiensteinau Nieder-Moos 0,80 € 0,80 € Freiensteinau Ober-Moos 0,70 € 0,85 € Freiensteinau Radmühl(Hess.) 0,60 € 0,60 € Freiensteinau Radmühl(Preuß.) 0,60 € 0,60 € Freiensteinau Reichlos 0,70 € 0,75 € Freiensteinau Reinhards 0,45 € 0,45 € Freiensteinau Salz 0,60 € 0,60 € Freiensteinau Weidenau 0,70 € 0,75 € Bodenrichtwert Grünland Bodenrichtwert -

Ahsgramerican Historical Society of Germans from Russia Germanic Origins Project Ni-Nzz

AHSGR American Historical Society of Germans From Russia Germanic Origins Project Legend: BV=a German village near the Black Sea . FN= German family name. FSL= First Settlers’ List. GL= a locality in the Germanies. GS= one of the German states. ML= Marriage List. RN= the name of a researcher who has verified one or more German origins. UC= unconfirmed. VV= a German Volga village. A word in bold indicates there is another entry regarding that word or phrase. Click on the bold word or phrase to go to that other entry. Red text calls attention to information for which verification is completed or well underway. Push the back button on your browser to return to the Germanic Origins Project home page. Ni-Nzz last updated Jan 2015 Ni?, Markgrafschaft Muehren: an unidentified place said by the Rosenheim FSL to be homeUC to Marx family. NicholasFN: go to Nicolaus. Nick{Johannes}: KS147 says Ni(c)k(no forename given) left Nidda near Buedingen heading for Jag.Poljanna in 1766. {Johannes} left Seelmann for Pfieffer {sic?} Seelmann in 1788 (Mai1798:Mv2710). Listed in Preuss in 1798 with a wife, children and step-children (Mai1798:Ps52). I could not find him in any published FSL. NickelFN: said by the Bangert FSL to be fromUC Rod an der Weil, Nassau-Usingen. For 1798 see Mai1798:Sr48. Nickel{A.Barbara}FN: said by the 1798 Galka census to be the maiden name of frau Fuchs{J.Kaspar} (Mai1798:Gk11). Nickel{J.Adam}FN: said by the Galka FSL to be fromUC Glauburg, Gelnhausen. For 1798 see Mai1798:Gk21. -

Ahsgramerican Historical Society of Germans from Russia

AHSGR American Historical Society of Germans From Russia Germanic Origins Project Legend: BV=a German village near the Black Sea . FN= German family name. FSL= First Settlers’ List. GL= a locality in the Germanies. GS= one of the German states. ML= Marriage List. RN= the name of a researcher who has verified one or more German origins. UC= unconfirmed. VV= a German Volga village. A word in bold indicates there is another entry regarding that word or phrase. Click on the bold word or phrase to go to that other entry. Red text calls attention to information for which verification is completed or well underway. Push the back button on your browser to return to the Germanic Origins Project home page. Bre-Bzz updated Mar 2015 BrechtFN: said by the Kromm version of the Jagodnaja Poljana FSL to be fromUC Redmar, Brunswick Duchy, sent here as an 1812 prisoner of war (p.137). BrechtFN: also see Bracht. BrechenmacherFN: said by the 1816 Glueckstal census (KS:677, 674, 233) to be fromUC Weyer, Elsass, but the GCRA could not find them in those church records. The 1816 census also said they came after a stay in Torschau, Hungary; another source said that the place was Weyer, Hungary. However, the GCRA found evidence they actually may have been in Klein-Ker, Hungary and probably were in Tscherwenka; see their book for detail. Also spelled Brachenmacher. BreckenheimGL, [Hesse-Darmstadt?]: is now a neighborhood some 6 miles E of Wiesbaden city centre, and was said by the Caesarsfeld FSL to be homeUC to a Wenzel family. -

Stand: November 2020

Stand: November 2020 Antragstellende beteiligte Bewillligung # Gemeinde / Kreis Aufgabenbereich Gemeinden vom Gemeindegruppe 1 Weiterstadt Darmstadt-Dieburg Erzhausen Standesamtsbezirk 25.09.2008 Beerfelden Hesseneck Haushalts- und 2 Mossautal Odenwald 25.09.2008 Rothenberg Rechnungswesen Sensbachtal Hünstetten Rheingau-Taunus- 3 Idstein Niedernhausen Standesamtsbezirk 26.11.2008 Kreis Waldems 4 Wahlsburg Kassel Oberweser Bauhof 11.03.2010 5 Groß-Umstadt Darmstadt-Dieburg Otzberg Errichtung eines Recyclinghofes 14.01.2009 Gemeinsames Beratungs- und Dienstleistungszentrum im Rheingau-Taunus- Rahmen der 6 Taunusstein 10 Gemeinden 02.09.2009 Kreis Haushaltswirtschaft auf der Grundlage der doppelten Buchführung Prüfung der elektrischen 7 Fuldatal Kassel 10 Gemeinden 26.11.2008 Anlagen und Betriebsmittel Sicherstellung des 8 Bischoffen Lahn-Dill-Kreis Hohenahr abwehrenden Brandschutzes 27.01.2009 und der allg. Hilfe 9 Kelkheim Main-Taunus-Kreis Eppstein Standesamtsbezirk 24.02.2009 Standesamtswesen, Kindergartenverwaltung, 10 Ebersburg Fulda Gersfeld 02.07.2009 Senioren- betreuung Fischbachtal 11 Reinheim Darmstadt-Dieburg Groß-Bieberau Werkstoffannahme 22.12.2009 Ober-Ramstadt 12 Mücke Vogelsbergkreis Gemünden Standesamtsbezirk 27.04.2009 (Felda) 13 Seligenstadt Offenbach Mainhausen Gemeinsames Personalamt 04.05.2009 Marburg- Cölbe 14 Wetter (Hessen) kommunale Jugendpflege 06.09.2009 Biedenkopf Lahntal Münchhausen Waldeck- Gemeinsame Steuer- und 15 Bromskirchen Allendorf (Eder) 27.04.2009 Frankenberg Personalverwaltung Antragstellende beteiligte -

Willkommen in Schrecksbach Im Rotkäppchenland

Willkommen in Schrecksbach im Rotkäppchenland Die Gemeinde im Zentrum der Schwalm INFORMATIONSBROSCHÜRE FÜR UNSERE GÄSTE UND BÜRGER ISNHALT VERZEICHNIS Inhaltsverzeichnis Grußwort des Bürgermeisters 1 Jugendarbeit in der Gemeinde Schrecksbach 13 Schrecksbach – Eine Einführung 2 Gesundheit und Soziales 14 Geschichte 2 Kirchen 16 Erklärung des Wappens der Gemeinde Schrecksbach 3 Vereine und Verbände 17 Die Ortsteile 3 Vereine und Gewerbe 18 Daten – Zahlen – Fakten 4 Sehenswürdigkeiten 20 Die Verwaltung als Dienstleister 4 Beratungsstellen U3 Bau- und Gewerbegebiet 7 Wichtige Rufnummern U3 Gastronomie und Unterkünfte 11 U3 = Umschlagseite Kindertagesstätte und Kindergarten 11 Schule am Metzenberg 12 Die Feuerwehren der Gemeinde Schrecksbach 13 Miteinander leben im Alter St. Martin Alten-, Wohn- und Pflegeheim Vollstationäre Pflege, Kurzzeitpflege Für ambulante Patienten Ambulanter Pflegedienst • Zusätzliche Betreuung nach dem Pflegeleistungs-Ergänzungsgesetz §45 SGB XI wenn man seine vertraute Umgebung nicht verlassen möchte Betreutes Wohnen • Häusliche Altenpflege Betreute Tagesgruppe für ambulante Patienten • Hauswirtschaftliche Versorgung Ehrenamtliche Hospizarbeit • Infos/Beratung nach §37 SGB XI Essen auf Rädern Qualität aus unserer Küche täglich frisch • Beratungsangebot und Vermittlung von individuellen Hilfen Cafeteria „Haus Martina“ St. Martin e.V. | 34626 Neukirchen | Lukanstraße 4 | Tel. 06694 5156-0 www.stmartin-neukirchen.de | [email protected] Grußwort des Bürgermeisters Herzlich willkommen in Schrecksbach! Sehr verehrte -

Anlage 5 Tabellen Der Natura 2000-Gebiete, Die Mit Ihrem Größeren Flächenanteil in Einem Der Nachbarregierungsbezirke Liegen

Anlage 5 Tabellen der Natura 2000-Gebiete, die mit ihrem größeren Flächenanteil in einem der Nachbarregierungsbezirke liegen und daher in der dortigen Natura 2000-Verordnung gesichert werden. Sie sind in dieser Anlage nur nachrichtlich aufgeführt und in der Übersichtskarte (Anlage 2) zu dieser Verordnung nur nachrichtlich mit dünner blauer Schraffur dargestellt oder bei sehr schmalen linienhaften Fließgewässergebieten mit einem textli- chen Hinweis in der Karte „Rechtliche Sicherung durch das benannte Nachbarregierungspräsidium“ versehen. Tabelle der RP-übergreifenden FFH-Gebiete mit dem größten Flächenanteil im Regierungsbezirk Darmstadt, die in der Übersichtkarte dieser Verord- nung mit dünner blauer Schraffur und Natura-Nummer nachrichtlich dargestellt werden NATURA_NR NAME HA REG_BEZ KREIS GEMEINDE 5518-301 Salzwiesen von Münzenberg 64.20 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Gießen, Münzenberg, Lich Gießen 5520-302 Talauen von Nidder und Hillersbach 253,90 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Vogelsbergkreis Gedern, Schotten bei Gedern und Burkhards Gießen 5520-306 Waldgebiete südlich und südwestlich 1680,60 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Vogelsbergkreis Hirzenhain, Nidda, Schot- von Schotten Gießen ten 5622-310 Steinaubachtal und Ürzeller Wasser 45,30 Darmstadt, Main-Kinzig-Kreis, Vogelsbergkreis Steinau an der Straße, Gießen Schlüchtern, Freiensteinau Tabelle der RP-übergreifenden schmalen linienhaften Fließgewässer-FFH-Gebiete mit dem größten Flächenanteil im Regierungsbezirk Darmstadt, die in der Übersichtkarte dieser Verordnung mit dem textlichen Hinweis -

Folgende Ortsteile Wurden Im Rahmen Des Breitbandausbaus Nordhessen Erschlossen

Folgende Ortsteile wurden im Rahmen des Breitbandausbaus Nordhessen erschlossen: Landkreis PLZ Gemeinde Ortsteil Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Heinebach Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Hergershausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Licherode Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Niederellenbach Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Oberellenbach Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Sterkelshausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36251 Bad Hersfeld Allmershausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36251 Bad Hersfeld Beiershausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36251 Bad Hersfeld Heenes Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36251 Bad Hersfeld Kohlhausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Blankenheim Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Breitenbach Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Iba Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Imshausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Lüdersdorf Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Rautenhausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Solz Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Breitenbach a. H. Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Gehau Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Hatterode Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Machtlos/B. Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Oberjossa Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36219 Cornberg Cornberg Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36219 Cornberg Königswald Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36219 Cornberg Rockensüß Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36289 Friedewald Friedewald Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36289 Friedewald Hillartshausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36289 Friedewald Lautenhausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36289 Friedewald Motzfeld Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36282 Hauneck Bodes Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36166 Haunetal -

Knüll-Schwalm-Bote Quartalseinleger

3. Quartal 2021 Juli - August - September Auf einen Blick! Ansprechpartner, Telefonnummern und E-Mail-Adressen, angebotene Leistungen und wichtige Adressen finden Sie hier. Für alle Gemeinden Notrufe und Polizei Verbraucherzentrale Hessen e. V. Polizei 110 Beratungsstelle Fritzlar Feuer, Unfall, Notruf 112 Fraumünsterstraße 23, 34560 Fritzlar Ärztlicher Notdienst Tel. 116 117 Öffnungszeiten: Zahnärztlicher Notdienst Montag, Mittoch und Donnerstag: 9.00 bis 13.00 Uhr Termintelefon.: 05622 / 712-9000 zu erfragen bei der Servicenummer Tel. 01 80 / 5 60 70 11 Offene Sprechstunde (ohne Terminvereinbarung): Dienstag: 14.00 bis 16.00 Uhr Frauenhaus Kurzberatung, max. 15 min Notruf bei Tag und Nacht Tel. 0 56 81 / 61 70 Sprechzeiten Beratungsstelle, Holzhäuser Str. 7, Schuldnerberatung 34576 Homberg (Efze) In Fritzlar, Gudensberg und Neukirchen nach vorheriger Terminvereinbarung unter Mittwoch 14:00 - 15:00 Uhr, Tel. 05622 / 712-9000 oder nach Vereinbarung Tel. 0 56 81 / 93 04 47 Tagespflege-Servicebüro Schwalm-Eder Stromversorgung Leitung/Ansprechpartnerin: Frau Gisela Kuhnert Service-Center: 0800-3250532 Mo.–Fr. 8.00-18.00 Uhr (kostenfrei) Öffnungszeiten: Entstörungsdienst Strom: 0800-3410134 täglich 0.00-24.00 Uhr (kostenfrei) werktags 9.00 bis 12.00 Uhr Internet: www.EnergieNetz-Mitte.de E-Mail:[email protected] (außer mittwochs) Sprechstunden: Abfall-Entsorgung dienstags 16.00 bis 19.00 Uhr und donnerstags 9.00 bis 11.00 Uhr Altreifenentsorgung oder nach Vereinbarung Jörg Krautwald, Hauptstr. 4, Tel./Fax: 56 02 / 32 53 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau, oder 01 73 / 2 86 75 48 Tageselternverein Felsberg und Schwalm-Eder e.V Sonderabfall-Kleinmengen Schwalm-Eder Tel. 0 56 62 / 9 39 00 80 Die Annahmestelle für Sonderabfall-Kleinmengen ist jeweils Donnerstag von Rotdornweg 2 34587 Felsberg-Böddiger 13.30 - 16.30 Uhr auf der Deponie in Wabern-Uttershausen. -

RP325 Cohn Marion R.Pdf

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People Jerusalem (CAHJP) PRIVATE COLLECTION MARION R. COHN – P 325 Xeroxed registers of birth, marriage and death Marion Rene Cohn was born in 1925 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany and raised in Germany and Romania until she immigrated to Israel (then Palestine) in 1940 and since then resided in Tel Aviv. She was among the very few women who have served with Royal British Air Forces and then the Israeli newly established Air Forces. For many years she was the editor of the Hasade magazine until she retired at the age of 60. Since then and for more than 30 years she has dedicated her life to the research of German Jews covering a period of three centuries, hundreds of locations, thousands of family trees and tens of thousands of individuals. Such endeavor wouldn’t have been able without the generous assistance of the many Registors (Standesbeamte), Mayors (Bürgermeister) and various kind people from throughout Germany. Per her request the entire collection and research was donated to the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem and the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt am Main. She passed away in 2015 and has left behind her one daughter, Maya, 4 grandchildren and a growing number of great grandchildren. 1 P 325 – Cohn This life-time collection is in memory of Marion Cohn's parents Consul Erich Mokrauer and Hetty nee Rosenblatt from Frankfurt am Main and dedicated to her daughter Maya Dick. Cohn's meticulously arranged collection is a valuable addition to our existing collections of genealogical material from Germany and will be much appreciated by genealogical researchers.