Access Provided by Your Local Institution at 04/11/11 12:25AM GMT the Composer Michael Hersch in 2007 Susan Forscher Weiss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Áé( Áfý%¯Ð¨Ý Ñ˛

559281bk Hersch 1/8/06 5:27 pm Page 8 AMERICAN CLASSICS MICHAEL HERSCH Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 Fracta Arraché Michael Hersch would like to thank the Argosy Foundation, Fran Richard, the staff and musicians of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Walton, Bournemouth Symphony Ignat Solzhenitsyn, George and Gene Rochberg, Jamie Hersch, Christopher Middleton, Orchestra Jessica Lustig, Michael Lutz, Glenn Petry, Albert Imperato, Louise Barder, and his wife Karen and daughter Abigail Hersch. Marin Alsop 8.559281 8 559281bk Hersch 1/8/06 5:27 pm Page 2 Michael Hersch (b.1971): Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 • Fracta • Arraché ierten Wiederholung der Anfangslinien überleitet. Eine choralartige, dunkel gefärbte Figur in Fagotten und Klari- Reihe sich steigernder Codas führt zum Augenblick der netten. Ist das vielleicht ein Gebet um Kraft gegen das Intensity and passion always increasing… conductor consistently programmed Hersch’s music Wahrheit: Tatsächlich endet die Symphonie mit einem Böse, das gleich ausgestrahlt werden wird? Auf jeden Fall This marking found in Michael Hersch’s Symphony No. 1 and helped to instill confidence that his voice was a Unisono-C der Glocken. Mag das Leben auch noch so wird der Hörer tatsächlich von dieser sorgenvollen Re- best sums up the American composer’s music. His worthy one. That relationship has continued to this day, düster sein, die Ausdauer wird doch belohnt. flexion durch ein kantiges, hüpfendes Thema „weggeris- output abounds with extreme shifts in dynamics and leading to the present disc of definitive recordings with Arraché, das jüngste Werk auf dieser CD, zeigt deut- sen“, das zu einem dichten, stachligen Allegro führt. -

Music: the Quintessential American Sound

Music: The Quintessential American Sound By Tim Smith The early years of the 21st century have yet to provide a clear-cut sense of where music in America is heading, but through the mixed signals, it's possible to draw some promising conclusions. Despite premature reports of its demise, the classical genre is still very much alive and kicking. American composers continue to create rewarding experiences for performers and listeners alike; most orchestras sound better than ever; most opera companies are enjoying increasingly sizable audiences, with particularly strong growth in the desirable 18- to-24-year-old category. Singer Norah Jones and her album "Come The pop music field -- from the cutting- Away With Me" captured eight Grammy Awards in 2003. edge to the mainstream to the retro -- is (Robert Mora, © 2002 Getty Images) still spreading its stylistic influences around a world that has never lost its appetite for the latest American sounds and stars. The Advent of Cyber Technology Technological advances continue to influence the whole spectrum of America's music in mostly positive ways. Composer Tod Machover has pioneered computer-generated "hyperinstruments" that electronically augment the properties of conventional instruments and expand a performer's options of controlling pitch, tempo, and all the other elements of music-making. Listeners are downloading not just the latest hit recordings, but also live classical concerts and opera performances via the Internet. Music organizations have been quick to add Web sites, giving regular and prospective patrons new opportunities to learn about works being performed and even to take music courses, not just buy tickets. -

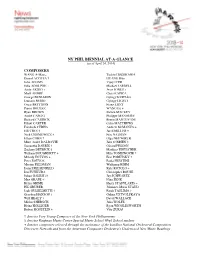

NY PHIL BIENNIAL AT-A-GLANCE COMPOSERS Daniel ACOSTA

NY PHIL BIENNIAL AT-A-GLANCE (as of April 10, 2014) COMPOSERS Daniel ACOSTA † Toshio HOSOKAWA John ADAMS HUANG Ruo Mark ANDRÉ Vijay IYER George BENJAMIN Michael JARRELL Luciano BERIO Chris KAPICA Oscar BETTISON György KURTÁG Pierre BOULEZ György LIGETI Ryan BROWN Franz LISZT André CAPLET Steven MACKEY Richard CARRICK Philippe MANOURY Elliott CARTER Bruno MANTOVANI Friedrich CERHA Colin MATTHEWS Elli CHOI † Eric NATHAN Nick CHOMOWICZ † Olga NEUWIRTH Ethan COHN † Jake O’BRIEN † Marc-André DALBAVIE Gérard PESSON Samantha DARRIS † Matthias PINTSCHER Zachary DETRICK § Milo PONIEWOZIK † Peter EÖTVÖS Eric PORETSKY † Morton FELDMAN Paola PRESTINI Daniel FELSENFELD Wolfgang RIHM Dai FUJIKURA Christopher ROUSE Julian GALESI §† Jay SCHWARTZ Helen GRIME Nina ŠENK HK GRUBER Johannes Maria STAUD Jack GULIELMETTI † Farah TASLIMA † Graydon HANSON † Galina USTVOLSKAYA Will HEALY † David WALLACE Michael HERSCH Julia WOLFE Heinz HOLLIGER Ryan WIGGLESWORTH Vito ZURAJ † denotes Very Young Composer of the New York Philharmonic § denotes Kaufman Music Center Special Music School High School student 2 Additional composers selected through the assistance of the EarShot National Orchestral Composition Discovery Network and from the American Composers Orchestra’s Underwood New Music Readings COMPOSERS’ COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN Austria Romania China Russia France Slovenia Germany Switzerland Hungary United Kingdom Italy United States Japan Venezuela WORLD PREMIERES Oscar BETTISON Threaded Madrigals (New York Philharmonic Commission) Zachary DETRICK (SMSHS student) Beyond There Julian GALESI (SMSHS student) Vote for Sheriff HUANG Ruo Chamber Concerto No. 2, The Lost Garden (World Premiere of chamber orchestra version) Michael HERSCH Of Sorrow Born: Seven Elegies (New York Philharmonic Commission) Chris KAPICA Fandanglish (New York Philharmonic Commission) Eric NATHAN As Above, So Below (New York Philharmonic Commission) Paola PRESTINI Eight Takes (New York Philharmonic Commission) Christopher ROUSE Symphony No. -

Music in the Making” (Formerly “Composer Conversation Series”)

For Immediate Release Contact: Stephen Sokolouski 651.292.4318 | [email protected] The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Classical Minnesota Public Radio, and American Composers Forum announce new season of “Music in the Making” (formerly “Composer Conversation Series”) 2015.16 Music in the Making conversations feature Michael Hersch, Derek Bermel, Meredith Monk, Steven Mackey and special guests at MPR’s UBS Forum, Amsterdam Bar & Hall, Walker Art Center’s William and Nadine McGuire Theater and Guthrie Theater SAINT PAUL, MN, September 22, 2015 — The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra (SPCO), Classical Minnesota Public Radio (MPR), and American Composers Forum (ACF) are pleased to announce the fourth season of Music in the Making. Formerly known as “Composer Conversation Series,” the new name “Music in the Making” emphasizes the series’ shift from a focus on composition to a broader, more collaborative conversation between composers and artists about music-making as a whole. Intended for music lovers of all stripes, this season’s events allows audiences to engage directly with the most original, prominent and prestigious voices in composition. The 2015.16 season will feature live interviews with distinctive creators Michael Hersch (with violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja), Derek Bermel, Meredith Monk and Steven Mackey (with composer/percussionist Jason Treuting & director Mark DeChiazza). The events will take place at venues across the Twin Cities and feature time devoted for audience Q&A and informal post-show receptions. This season welcomes two new hosts: Classical MPR’s Steve Seel and the Walker Arts Center’s Director and Senior Curator of Performing Arts Philip Bither. Previous seasons featured live interviews with distinguished guests such as Kevin Puts, Bryce Dessner, Caroline Shaw, Richard Reed Parry, Fred Lerdahl, Missy Mazzoli, John Luther Adams, Vivian Fung, John Harbison, Timo Andres, Gabriel Kahane, Shawn Jaeger, Dawn Upshaw, Laurie Anderson and Sufjan Stevens among others. -

Ny Phil Biennial At-A-Glance Composers

NY PHIL BIENNIAL AT-A-GLANCE (as of April 24, 2014) COMPOSERS WANG A-Mao + Toshio HOSOKAWA Daniel ACOSTA † HUANG Ruo John ADAMS Vijay IYER Julia ADOLPHE + Michael JARRELL Andy AKIHO + Jesse JONES + Mark ANDRÉ Chris KAPICA George BENJAMIN György KURTÁG Luciano BERIO György LIGETI Oscar BETTISON Franz LISZT Pierre BOULEZ WANG Lu + Ryan BROWN Steven MACKEY André CAPLET Philippe MANOURY Richard CARRICK Bruno MANTOVANI Elliott CARTER Colin MATTHEWS Friedrich CERHA Andrew McMANUS + Elli CHOI † Jared MILLER + Nick CHOMOWICZ † Eric NATHAN Ethan COHN † Olga NEUWIRTH Marc-André DALBAVIE Jake O’BRIEN † Samantha DARRIS † Gérard PESSON Zachary DETRICK § Matthias PINTSCHER William DOUGHERTY + Milo PONIEWOZIK † Melody EÖTVÖS + Eric PORETSKY † Peter EÖTVÖS Paola PRESTINI Morton FELDMAN Wolfgang RIHM Daniel FELSENFELD Kyle ROTOLO + Dai FUJIKURA Christopher ROUSE Julian GALESI §† Jay SCHWARTZ Max GRAFE + Nina ŠENK Helen GRIME Harry STAFYLAKIS + HK GRUBER Johannes Maria STAUD Jack GULIELMETTI † Farah TASLIMA † Graydon HANSON † Galina USTVOLSKAYA Will HEALY † David WALLACE Michael HERSCH Julia WOLFE Heinz HOLLIGER Ryan WIGGLESWORTH Robert HONSTEIN + Vito ZURAJ † denotes Very Young Composer of the New York Philharmonic § denotes Kaufman Music Center Special Music School High School student + denotes composers selected through the assistance of the EarShot National Orchestral Composition Discovery Network and from the American Composers Orchestra’s Underwood New Music Readings 2 COMPOSERS’ COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN Australia Japan Austria Romania Canada Russia China Slovenia France Switzerland Germany United Kingdom Hungary United States Italy Venezuela WORLD PREMIERES Julia ADOLPH Dark Sand, Sifting Light Andy AKIHO Tarnished Mirrors Oscar BETTISON Threaded Madrigals * Zachary DETRICK (SMSHS student) Beyond There Melody EÖTVÖS Beetles, Dragons, and Dreamers Julian GALESI (SMSHS student) Vote for Sheriff Max GRAFE Bismuth: Variations for Orchestra HUANG Ruo Chamber Concerto No. -

Biography 2021

Michael Hersch A composer of “uncompromising brilliance” (The Washington Post) whose work has been described by The New York Times as “viscerally gripping and emotionally transformative music ... claustrophobic and exhilarating at once, with moments of sublime beauty nestled inside thickets of dark virtuosity,” Michael Hersch is widely considered among the most gifted composers of his generation. The Philadelphia In- quirer has written “Hersch’s language never hesitates to leap into the abyss - and in ways that, for some listeners, go straight to parts of the soul that few living composers touch.” Composer Georg Friedrich Haas has called Hersch “… an astonishing musician. He is one of those rare artists who personally is to- tally melded together with their art.” Recent events and premieres include his Violin Concerto at the Lucerne Festival in Switzerland and the Avanti Festival in Helsinki; new productions of his monodrama, On the Threshold of Winter, in Chicago, Salt Lake City, and Washington D.C., and his I hope we get a chance to visit soon at the Ojai and Aldeburgh Festivals, where Mr. Hersch was a 2018 featured compos- er. Other recent premieres include his 10-hour chamber cycle, sew me into a shroud of leaves, a work which occupied the composer for fifteen years, at the 2019 Wien Modern Festival. 2021 will see the pre- miere of his new opera, Poppaea, in Vienna and Basel as part of the Wien Modern Festival in a co-pro- duction with ZeitRäume Basel and Gare du Nord Basel / Netzwerk zur Entwicklung formatübergreifende Musiktheaterformen. During the 2019/20 season, Mr. -

A Soprano of "Fearlessness and Consummate

A soprano of "fearlessness and consummate artistry" (Opera News), Ah Young Hong has interpreted a vast array of repertoire, ranging from the music of Monteverdi, Bach, Mozart, and Poulenc, to works of Shostakovich, Babbitt, Haas, and Kurtág. Widely recognized for her work in Michael Hersch's monodrama, On the Threshold of Winter, The New York Times praised Ms. Hong’s performance in the world premiere as "the opera's blazing, lone star." In a recent production directed by the soprano, The Chicago Tribune called her "absolutely riveting," and the Chicago Classical Review noted the soprano's "fearless presence, wielding her unamplified, bell-like voice like a weaponized instrument. Hong delivered a tour de force vocal performance in this almost unfathomably difficult music-attacking the dizzying high notes with surprising power, racing through the rapid-fire desperation of agitated sections, and bringing a numbed, toneless sprechstimme and contralto-like darkness to the low tessitura." Other operatic performances by Ms. Hong include the title role in Monteverdi's L'incoronazione di Poppea, Morgana in Handel's Alcina, Gilda in Verdi's Rigoletto, Fortuna and Minerva in Monteverdi's Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, and Asteria in Handel's Tamerlano. She has also appeared with Opera Lafayette in Rebel and Francoeur's Zélindor, roi des Sylphes at the Rose Theater in Lincoln Center and as La Musique in Charpentier's Les Arts Florissants at the Kennedy Center. At the 2020 Wien Modern Festival, Ms. Hong has been engaged to sing the lead role in the world premiere of Michael Hersch’s POPPAEA. -

Invigorating the American Orchestral Tradition Through New Music

FEARLESS PROGRAMMING: INVIGORATING THE AMERICAN ORCHESTRAL TRADITION THROUGH NEW MUSIC Octavio Más-Arocas A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2016 Committee: Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor Timothy F. Messer-Kruse Graduate Faculty Representative Marilyn Shrude Kenneth Thompson © 2016 Octavio Más-Arocas All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor Despite great efforts by American composers, their prodigious musical output has been mostly ignored by American orchestras. Works by living American composers account for an annual average of only 6% of all the music performed by American orchestras, while works by living composers of all nationalities combined totals a meager 11%. This study examines some of the historical breaking points in the relationship between American orchestras and new music. Five exceptional orchestras are cited, the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Atlanta Symphony, and the Seattle Symphony, that are thriving while successfully incorporating new music in their programing. This document draws attention to the significant role new music can play in the future of American orchestras by analyzing the programing of new music and projects that support composers, identifying innovative orchestral leaders and composers who have successfully served in advisory positions, and by recognizing and discussing the many creative strategies orchestras are using today. This document attempts to increase the understanding of the need for change in concert programing while highlighting several thrilling examples of innovative strategies that are making an essential contribution to the future of orchestral music. -

Michael Hersch End Stages Violin Concerto

Michael Hersch end stages violin concerto Patricia Kopatchinskaja International Contemporary Ensemble Orpheus Chamber Orchestra Violin Concerto (2015) end stages (2016) There is no superficial beauty or decoration, and no compromises— everything is in the right place, crafted as if with a scalpel. -Patricia Kopatchinskaja There were years when Michael Hersch wrote often for orchestra, and years when he disappeared entirely from public view, writing only for his own hands as a pianist. He has been the recipient of many accolades, and he has been inundated with cancer diagnoses among his closest people, including his own ordeal. Through headwinds and tailwinds, Hersch has followed a remarkably durable inner compass: He always points himself, unflinchingly, toward the more vulnerable corners of human experience. As The Philadelphia Inquirer has noted, “Hersch’s language never hesitates to leap into the abyss—and in ways that, for some listeners, go straight to parts of the soul that few living composers touch.” Hersch’s strongest champions have always been the performers who share (and relish) the responsibility for externalizing such sensitive and private thoughts. The works recorded here—the Violin Concerto commissioned by Patricia Kopatchinskaja, and end stages written for the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra—show just how potent it can be when entire ensembles of virtuoso players invest themselves in Hersch’s worldview. **** Kopatchinskaja first encountered Hersch through an online recording that she happened upon while searching the Internet on a sleepless night: “My husband and I were lucky enough to hear a piece that really we didn’t expect to hear in our days. And I thought, I want to meet this person, I want to speak with this person, I want to hear more music from him, and who knows, maybe once we will get a commission for him?” In her capacity as an Artistic Partner with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Kopatchinskaja proposed commissioning a new work from Hersch. -

OJAI at BERKELEY PATRICIA KOPATCHINSKAJA, Music DIRECTOR

OJAI AT BERKELEY PATRICIA KOPATCHINSKAJA, MuSIC DIRECTOR The four programs presented in Berkeley this month mark the eighth year of artistic partnership between the Ojai Music Festival and Cal Performances and represent the combined efforts of two great arts organizations committed to innovative and adventur- ous programming. themes from the Latin Requiem mass and fea- tures music by composers such as Scelsi, Biber, and ustwols kaja. It was premiered in North America last week, as part of the Ojai Music Festival. The violinist will revive Bye Bye Bee - tho ven here at uC Berkeley and at the Alde - burgh Festival later this summer. György Ligeti’s Violin Concerto is a feature of Kopatchinskaja’s season, with other highlights including performances with the Mahler Cham - ber Orchestra at the Enescu Festival in Bucha - rest under Jonathan Stockhammer and concerts with Orches tra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI. Last season’s highlights included Kopatch - inskaja’s work as artist-in-residence at major European venues and festivals including the Ber lin Konzerthaus, the Lucerne Festival, and London’s Wigmore Hall, as well as perform- ances with Sir Simon Rattle and the Berlin Phil harmonic, and the London Philharmonic Or ches tra in London and New York under Vladimir Jurowski. Chamber music is immensely important to Kopatchinskaja and she performs regularly Marco Borggreve with artists including Markus Hinterhäuser, Violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja’s versatility re- Polina Leschenko, Anthony Romaniuk, and Jay veals itself through her diverse repertoire, which Camp bell at such leading venues as the Berlin ranges from Baroque and Classical music, often Konzerthaus, Vienna Konzerthaus, and Con - played on gut strings, to new commissions and cert gebouw Amsterdam. -

MICHAEL HERSCH Images from a Closed Ward the Blairstringquartet Michael Hersch Images from a Closed Ward

MICHAEL HERSCH images from a closed ward The BlairStringQuartet michael hersch images from a closed ward Images From a Closed Ward (2010) I 3:41 II 1:13 III 3:30 IV 1:46 V 2:41 VI 1:03 VII 2:55 VIII 1:16 IX 4:01 X 2:01 XI 9:36 XII 4:45 XIII 3:45 - — 42:13 — - The Blair String Quartet: Christian Teal, violin I Cornelia Heard, violin II John Kochanowski, viola Felix Wang, cello innova 884 © Michael Hersch. All Rights Reserved, 2014. innova® Recordings is the label of the American Composers Forum. www.innova.mu www.michaelhersch.com innova 884 On Michael Hersch’s Images from a Closed Ward by Aaron Grad Michael Hersch’s string quartet, Images from a Closed Ward, has in its origins an encounter in Rome in 2000. The Ameri- can artist Michael Mazur (1935-2009) had created a series of etchings to accompany Robert Pinsky’s new translation of Dante’s Inferno, and Mazur’s works were on display at the American Academy in Rome while the then 29-year-old Hersch was there as a Rome Prize Fellow. During their time in the Eternal City, Hersch and Mazur seemed to recognize each other as kindred spirits. In 2003, Mazur provided artwork and commentary for Hersch’s first CD release, a collection of his chamber music performed by the String Soloists of the Berlin Philharmonic. In describing the young composer’s style, Mazur noted, “I am struck by what might constitute an analogy with painting and with my own work in particular. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2010

f^"^' 4iiKZ^ *i • , 1 • • 1 •A * "'^^fc-^w^ '1 !iC 2' i»f 1 { Li'^Va-i f^- --^ ^^ ' ,i.jba..j»ii^- - 1 . , ^1^ '^ -r L IpgC- . ;^ ' -^^isu^^i^^^^lHB^^ ^iv-i^ .^'^^^^*;.;'^--^si^^lS " ,. '^**r\jj 11^ -*ir ' -J " 5 - - '-^krm--.g-^ '^ ^^ l>.7 ^fc^ _^ ' -.JSidW" J^^^ '^ Ip^ -^'^r3m Bm^ ^ ^^^ 1 '2 '" ?* Tanglewood SUMMER 2010 Dale Chihuly ScHANTZ Galleries CONTEMPORARY GLASS 3 ELM STREET STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 413- 298 -3044 [email protected] Bright Green and Pink Seaform Set 8 x 15 x 9' photo: Scott Mitchell Leen NAGEMENT We/LL m^Jce^ it easy to m^t/e^yourpovtfoUo. © Copyngtit 2009 Ned Davis Research. Inc. Further distribution prohibited without prior permission All Rigtits Reserved. See NDR Disclaimer at www, ndr.com/copyright.html. For data vendor disclaimers refer to wv/w.ndr,com/vendorinfo/. May 11, 2001 (sell) May 10, 2002 (sell) November 15, 2007 (sell) "Don't get too scientific.just ask yourself; "If [the NASDAQ] pierces the 1600 level "The obvious answer is a temporary does it feel like a recession? We don't again, the prudent investor will not hold position in cash." think it feels as bad as 1990-1991, but it out for another relief rally...the NASDAQ The stock market fell 48.9% after is bad enougli." is setting up for a retest of the September that sell signal. [2007] lows of the 1400S." The stock market fell 16.5% until our next buy signal. June (sell) October 11, 2002 (buy) 9, 2008 September 28, 2001 (buy) "It will make sense to reduce equity "The VIX broke 50 [on October loth], "Equity valuations are better than they exposure." and that is my buy signal this time." have been in years." The stock market rose 80% until our March 6, 2009 (buy) The stock market rose 10.4% until our next sell signal.