Invigorating the American Orchestral Tradition Through New Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

John Adams Doctor Atomic CONDUCTOR Opera in two acts Alan Gilbert Libretto by Peter Sellars, PRODUCTION adapted from original sources Penny Woolcock Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm SET DESIGNER Julian Crouch COSTUME DESIGNER New Production Catherine Zuber LIGHTING DESIGNER Brian MacDevitt CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Doctor Atomic was made Andrew Dawson possible by a generous gift from Agnes Varis VIDEO DESIGN and Karl Leichtman. Leo Warner & Mark Grimmer for Fifty Nine Productions Ltd. SOUND DESIGNER Mark Grey GENERAL MANAGER The commission of Doctor Atomic and the original San Peter Gelb Francisco Opera production were made possible by a generous gift from Roberta Bialek. MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Doctor Atomic is a co-production with English National Opera. 2008–09 Season The 8th Metropolitan Opera performance of John Adams’s Doctor Atomic Conductor Alan Gilbert in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Edward Teller Richard Paul Fink J. Robert Oppenheimer Gerald Finley Robert Wilson Thomas Glenn Kitty Oppenheimer Sasha Cooke General Leslie Groves Eric Owens Frank Hubbard Earle Patriarco Captain James Nolan Roger Honeywell Pasqualita Meredith Arwady Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from the Neubauer Family Foundation. Additional support for this Live in HD transmission and subsequent broadcast on PBS is provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Gerald Finley Chorus Master Donald Palumbo (foreground) as Musical Preparation Linda Hall, Howard Watkins, Caren Levine, J. -

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

Pizzazz on the Podium

Montage Art, books, diverse creations 14 Open Book 15 Bishop Redux 16 Kosher Delights 17 And the War Came 18 Off the Shelf 19 Chapter and Verse 20 Volleys in F# Major places this orchestra square- ly at the center of cultural and intellectual discourse.” The Philharmonic sounds better than it has in decades, too, because Gilbert has im- proved morale, changed the seating plan, and worked on details of tone and balance— even the much-reviled acoustics of Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center sound Alan Gilbert less jagged now. The conducting conductor is also pre- CHRIS LEE the New York Pizzazz on the Podium Philharmonic pared to be surprised: at Avery Fisher to him, his job is both Alan Gilbert’s music that should be heard Hall in Lincoln to lead and take in Center what the musicians by richard dyer are offering. The unexpected hit of his first season ike his celebrated predecessor as diverse as György Ligeti and Wynton was Ligeti’s avant-garde opera, Le Grand Leonard Bernstein ’39, D.Mus. Marsalis, named a composer-in-residence Macabre, in a staging by visual artist Doug ’67, Alan Gilbert ’89 seems to en- (Magnus Lindberg), and started speaking Fitch ’81, a friend who had tutored art in joy whipping up a whirlwind and informally to the audience, as Bernstein Adams House when Gilbert was in col- then taking it for an exhilarating sometimes did. His programs are full of lege. To publicize the opera, Gilbert ap- L ride. Though only in his second year on interconnections and his seasons add peared in three homespun videos that the the job, the second Harvard-educated mu- up; Gilbert has said that every piece tells Philharmonic posted on YouTube; Death, sic director of the New York Philharmonic a story, and every program should, too. -

Other Minds 19 Official Program

SFJAZZ CENTER SFJAZZ MINDS OTHER OTHER 19 MARCH 1ST, 2014 1ST, MARCH A FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28 FEBRUARY OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC Find Left of the Dial in print or online at sfbg.com WELCOME A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED TO OTHER MINDS 19 NEW MUSIC The 19th Other Minds Festival is 2 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director presented by Other Minds in association 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and SFJazz Center 11 Opening Night Gala 13 Concert 1 All festival concerts take place in Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the new SFJAZZ Center. 14 Concert 1 Program Notes Congratulations to Randall Kline and SFJAZZ 17 Concert 2 on the successful launch of their new home 19 Concert 2 Program Notes venue. This year, for the fi rst time, the Other Minds Festival focuses exclusively on compos- 20 Other Minds 18 Performers ers from Northern California. 26 Other Minds 18 Composers 35 About Other Minds 36 Festival Supporters 40 About The Festival This booklet © 2014 Other Minds. All rights reserved. Thanks to Adah Bakalinsky for underwriting the printing of our OM 19 program booklet. MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WELCOME TO OTHER MINDS 19 Ever since the dawn of “modern music” in the U.S., the San Francisco Bay Area has been a leading force in exploring new territory. In 1914 it was Henry Cowell leading the way with his tone clusters and strumming directly on the strings of the concert grand, then his students Lou Harrison and John Cage in the 30s with their percussion revolution, and the protégés of Robert Erickson in the Fifties with their focus on graphic scores and improvisation, and the SF Tape Music Center’s live electronic pioneers Subotnick, Oliveros, Sender, and others in the Sixties, alongside Terry Riley, Steve Reich and La Monte Young and their new minimalism. -

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Announces 2019 New Music Festival

Media contacts Linda Moxley, VP of Marketing & Communications 410.783.8020 [email protected] Devon Maloney, Director of Communications 410.783.8071 [email protected] For Immediate Release Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Announces 2019 New Music Festival Baltimore (April 18, 2019) Under the leadership of Music Director Marin Alsop, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) announces the 2019 New Music Festival. Launched by Alsop and the BSO in 2017, the New Music Festival brings contemporary classical music to Baltimore from June 19-22. The 2019 New Music Festival celebrates women composers ahead of the BSO’s 2019-20 season, which highlights women in music in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the U.S. Performances include the Baltimore premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s Low Brass Concerto, a BSO co- commission, as well as the world premiere of Anna Clyne’s cello concerto, Dance, with Inbal Segev. “I’m thrilled that this year’s New Music Festival features such an outstanding group of contemporary composers, who happen to be women!” said Alsop. “Each piece of music that we’ve programmed tells a unique and compelling story, and we are proud to present a range of voices and perspectives that showcases some of the most inspired work happening in classical composition today.” The 2019 New Music Festival kicks off on Wednesday, June 19 when composer Sarah Kirkland Snider participates in a discussion on her composition process at Red Emma’s Bookstore Café. On Thursday, June 20, Associate Conductor Nicholas Hersh leads members of the BSO and Shara Nova, also known as My Brightest Diamond, in a free concert at the Ottobar. -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

Rmc193chiprograml5.Pdf

SATURDAY APRIL 29, 2017 | 7:30 PM | ROCKEFELLER CHAPEL A TRIPTYCH: Earth, Moon, Peace Works of Augusta Read Thomas Played by Spektral Quartet and Third Coast Percussion ROCKEFELLER CHAPEL | UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OF UNIVERSITY 2 PROGRAM The program is performed without intermission, although there will be brief pauses for resetting the stage. You are warmly invited to a wine and cheese reception here in the Chapel after the concert, with refreshments served from the west transept. You will also find CDs on sale. RAINBOW BRIDGE TO PARADISE SELENE Moon Chariot Rituals 2016 2015 3 Russell Rolen CELLO Spektral Quartet Third Coast Percussion and CHI CHI | A TRIPTYCH: EARTH, MOON, PEACE CHI for string quartet RESOUNDING EARTH 2017 World première 2012 I CHI vital life force I INVOCATION pulse radiance II AURA atmospheres, colors, vibrations II PRAYER star dust orbits III MERIDIANS zeniths III MANTRA ceremonial time shapes IV CHAKRAS center of spiritual power in the body IV REVERIE CARILLON crystal lattice Spektral Quartet Third Coast Percussion Clara Lyon VIOLIN David Skidmore Maeve Feinberg VIOLIN Peter Martin Doyle Armbrust VIOLA Robert Dillon Russell Rolen CELLO Sean Connors ABOUT THIS CONCERT Like most works of art, tonight’s concert came into Enter Spektral Quartet (or re-enter, for this being through the confluence of flashes of desire, conversation also had begun, allegro con spirito, some snippets of conversation, and the sudden alignment of eons before). On March 7, 2015, the cosmic lights went energies sparked by the commissioning of a new work. green and we knew we had a program: Selene, to be The flash of desire came just over three years ago. -

For Release: Tk, 2013

FOR RELEASE: January 23, 2013 SUPPLEMENT CHRISTOPHER ROUSE, The Marie-Josée Kravis COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE WORLD PREMIERE of SYMPHONY NO. 4 at the NY PHIL BIENNIAL New York Premiere of REQUIEM To Open Spring For Music Festival at Carnegie Hall New York Premiere of OBOE CONCERTO with Principal Oboe Liang Wang RAPTURE at Home and on ASIA / WINTER 2014 Tour Rouse To Advise on CONTACT!, the New-Music Series, Including New Partnership with 92nd Street Y ____________________________________ “What I’ve always loved most about the Philharmonic is that they play as though it’s a matter of life or death. The energy, excitement, commitment, and intensity are so exciting and wonderful for a composer. Some of the very best performances I’ve ever had have been by the Philharmonic.” — Christopher Rouse _______________________________________ American composer Christopher Rouse will return in the 2013–14 season to continue his two- year tenure as the Philharmonic’s Marie-Josée Kravis Composer-in-Residence. The second person to hold the Composer-in-Residence title since Alan Gilbert’s inaugural season, following Magnus Lindberg, Mr. Rouse’s compositions and musical insights will be highlighted on subscription programs; in the Philharmonic’s appearance at the Spring For Music festival; in the NY PHIL BIENNIAL; on CONTACT! events; and in the ASIA / WINTER 2014 tour. Mr. Rouse said: “Part of the experience of music should be an exposure to the pulsation of life as we know it, rather than as people in the 18th or 19th century might have known it. It is wonderful that Alan is so supportive of contemporary music and so involved in performing and programming it.” 2 Alan Gilbert said: “I’ve always said and long felt that Chris Rouse is one of the really important composers working today. -

2018/19 Utah Symphony | Utah Opera Season Calendar

2018/19 UTAH SYMPHONY | UTAH OPERA SEASON CALENDAR DATE TIME CONCERT PROGRAM CONDUCTOR / ARTISTS VENUE SERIES 11 7:00 PM 59th Annual Salute to Youth Conner Gray Covington conductor AH 14 & 15 7:30 PM Bernstein on Broadway Teddy Abrams conductor Morgan James vocalist AH Barlow Bradford Thierry Fischer conductor chorus director ANDREW NORMAN Suspend a fantasy for piano and orchestra Jason Hardink piano Kirstin Chávez mezzo-soprano 21 & 22 7:30 PM Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 “Choral” Joélle Harvey soprano AH A, D Issachah Savage tenor Patrick Carfizzi bass-baritone SEPTEMBER Utah Symphony Chorus University of Utah Choirs GERSHWIN An American in Paris 28 7:30 PM An American in Paris RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Thierry Fischer conductor Alexandre Tharaud piano AH B, E 29 5:30 PM SCHUBERT Symphony No. 9 “The Great C Major” 13 7:30 PM 15 7:00 PM Robert Tweten conductor Vera Calábria director 17 7:00 PM Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet CT Joshua Dennis Romeo Anya Matanoviĉ Juliet 19 7:30 PM 21 2:00 PM 26 7:30 PM BERNSTEIN Three Dances from Fancy Free OCTOBER Tchaikovsky’s 4th & The Red Violin 27 5:30 PM JOHN CORIGLIANO Violin Concerto “The Red Violin” Andrew Litton conductor Philippe Quint violin AH B, E 26 10:00 AM LITTON/QUINT FINISHING TOUCHES OPEN REHEARSAL TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 4 2 & 3 7:00 PM Ghostbusters in Concert Peter Bernstein conductor Utah Symphony AH Thierry Fischer conductor Garnett Bruce director James Sale lighting designer Jonathan Johnson Candide B, E 9 7:30 PM Bernstein’s Candide with the Utah Symphony BERNSTEIN Candide Lauren Snouffer Cunegonde Hugh Russell Dr. -

ANNIE GOSFIELD, Whom the BBC Called “A One Woman Hadron

ANNIE GOSFIELD, whom the BBC called “A one woman Hadron collider,” lives in New York City and works on the boundaries between notated and improvised music, electronic and acoustic sounds, refined timbres and noise. Her music is often inspired by the inherent beauty of found sounds, noise, and machinery. She was dubbed “a master of musical feedback” by The New York Times, who wrote “Ms. Gosfield’s choice of sounds — which on this occasion included radio static, the signals transmitted by the Soviet satellite Sputnik I, and recordings of Hurricane Sandy — are never a mere gimmick. Her extraordinary command of texture and timbre means that whether she is working with a solo cello or with the ensemble she calls her “21st-century avant noisy dream band,” she is able to conjure up a palette of saturated and heady hues.” In 2017 Gosfield collaborated with Yuval Sharon and the Los Angeles Philharmonic on the multi-site opera “War of the Worlds.” This large-scale, citywide collaborative performance was a powerful engagement with public life, bringing opera out of the concert hall and into the streets. Three defunct air raid sirens located in downtown Los Angeles were re-purposed into public speakers to broadcast a free, live performance from Walt Disney Concert Hall. The sirens also served as remote sites for singers and musicians to report back to the concert hall from the street. The notorious 1938 radio drama created by Orson Welles came to new life, directed by The Industry’s Yuval Sharon, conducted by Christopher Rountree and narrated by Sigourney Weaver. -

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

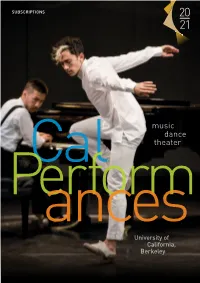

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories.