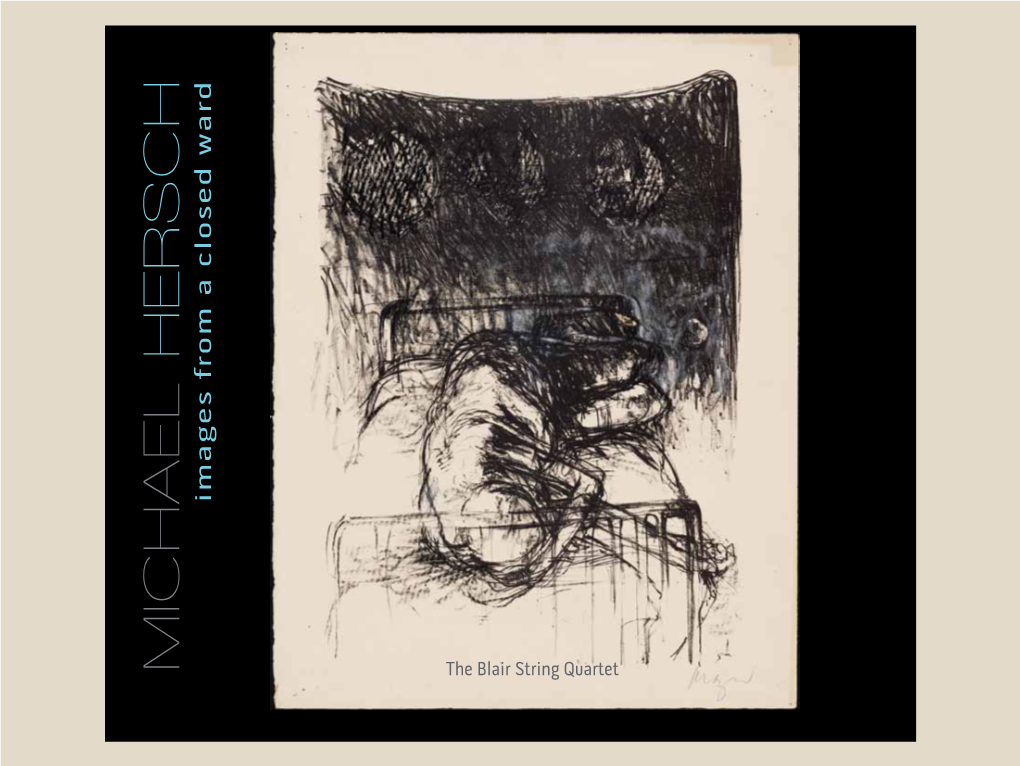

MICHAEL HERSCH Images from a Closed Ward the Blairstringquartet Michael Hersch Images from a Closed Ward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Ojai North Music Festival

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Thursday–Saturday, June 19–21, 2014 Hertz Hall Ojai North Music Festival Jeremy Denk Music Director, 2014 Ojai Music Festival Thomas W. Morris Artistic Director, Ojai Music Festival Matías Tarnopolsky Executive and Artistic Director, Cal Performances Robert Spano, conductor Storm Large, vocalist Timo Andres, piano Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone Kim Josephson, baritone Dominic Armstrong, tenor Ashraf Sewailam, bass-baritone Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Peabody Southwell, mezzo-soprano Keith Jameson, tenor Jennifer Zetlan, soprano The Knights Eric Jacobsen, conductor Brooklyn Rider Uri Caine Ensemble Hudson Shad Ojai Festival Singers Kevin Fox, conductor Ojai North is a co-production of the Ojai Music Festival and Cal Performances. Ojai North is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Liz and Greg Lutz. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 13 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday–Saturday, June 19–21, 2014 Hertz Hall Ojai North Music Festival FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday, June <D, =;<?, Cpm Welcome : Cal Performances Executive and Artistic Director Matías Tarnopolsky Concert: Bay Area première of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) plus Brooklyn Rider plays Haydn Brooklyn Rider Johnny Gandelsman, violin Colin Jacobsen, violin Nicholas Cords, viola Eric Jacobsen, cello The Knights Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone Dominic Armstrong, tenor Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Keith Jameson, tenor Kim Josephson, baritone Ashraf Sewailam, bass-baritone Peabody Southwell, mezzo-soprano Jennifer Zetlan, soprano Mary Birnbaum, director Robert Spano, conductor Friday, June =;, =;<?, A:>;pm Talk: The creative team of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) —Jeremy Denk, Steven Stucky, and Mary Birnbaum—in a conversation moderated by Matías Tarnopolsky PLAYBILL FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Cpm Concert: Second Bay Area performance of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) plus Brooklyn Rider plays Haydn Same performers as on Thursday evening. -

Áé( Áfý%¯Ð¨Ý Ñ˛

559281bk Hersch 1/8/06 5:27 pm Page 8 AMERICAN CLASSICS MICHAEL HERSCH Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 Fracta Arraché Michael Hersch would like to thank the Argosy Foundation, Fran Richard, the staff and musicians of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Walton, Bournemouth Symphony Ignat Solzhenitsyn, George and Gene Rochberg, Jamie Hersch, Christopher Middleton, Orchestra Jessica Lustig, Michael Lutz, Glenn Petry, Albert Imperato, Louise Barder, and his wife Karen and daughter Abigail Hersch. Marin Alsop 8.559281 8 559281bk Hersch 1/8/06 5:27 pm Page 2 Michael Hersch (b.1971): Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 • Fracta • Arraché ierten Wiederholung der Anfangslinien überleitet. Eine choralartige, dunkel gefärbte Figur in Fagotten und Klari- Reihe sich steigernder Codas führt zum Augenblick der netten. Ist das vielleicht ein Gebet um Kraft gegen das Intensity and passion always increasing… conductor consistently programmed Hersch’s music Wahrheit: Tatsächlich endet die Symphonie mit einem Böse, das gleich ausgestrahlt werden wird? Auf jeden Fall This marking found in Michael Hersch’s Symphony No. 1 and helped to instill confidence that his voice was a Unisono-C der Glocken. Mag das Leben auch noch so wird der Hörer tatsächlich von dieser sorgenvollen Re- best sums up the American composer’s music. His worthy one. That relationship has continued to this day, düster sein, die Ausdauer wird doch belohnt. flexion durch ein kantiges, hüpfendes Thema „weggeris- output abounds with extreme shifts in dynamics and leading to the present disc of definitive recordings with Arraché, das jüngste Werk auf dieser CD, zeigt deut- sen“, das zu einem dichten, stachligen Allegro führt. -

Music: the Quintessential American Sound

Music: The Quintessential American Sound By Tim Smith The early years of the 21st century have yet to provide a clear-cut sense of where music in America is heading, but through the mixed signals, it's possible to draw some promising conclusions. Despite premature reports of its demise, the classical genre is still very much alive and kicking. American composers continue to create rewarding experiences for performers and listeners alike; most orchestras sound better than ever; most opera companies are enjoying increasingly sizable audiences, with particularly strong growth in the desirable 18- to-24-year-old category. Singer Norah Jones and her album "Come The pop music field -- from the cutting- Away With Me" captured eight Grammy Awards in 2003. edge to the mainstream to the retro -- is (Robert Mora, © 2002 Getty Images) still spreading its stylistic influences around a world that has never lost its appetite for the latest American sounds and stars. The Advent of Cyber Technology Technological advances continue to influence the whole spectrum of America's music in mostly positive ways. Composer Tod Machover has pioneered computer-generated "hyperinstruments" that electronically augment the properties of conventional instruments and expand a performer's options of controlling pitch, tempo, and all the other elements of music-making. Listeners are downloading not just the latest hit recordings, but also live classical concerts and opera performances via the Internet. Music organizations have been quick to add Web sites, giving regular and prospective patrons new opportunities to learn about works being performed and even to take music courses, not just buy tickets. -

A Performance Guide to George Rochberg's Caprice Variations For

A Performance Guide to George Rochberg’s Caprice Variations for Solo Violin by YUNG-YU LIN A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by YUNG-YU LIN 2020 A Performance Guide to George Rochberg’s Caprice Variations for Solo Violin YUNG-YU LIN Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto 2020 Abstract The American composer George Rochberg’s Caprice Variations, composed in 1970, draws on a vast array of historical stylistic references from the Baroque to the modern musical periods. For Rochberg serialism, arguably the most influential compositional technique of the twentieth century, could no longer convey the full extent of what he wanted to express in his music. After the death of his son Paul in 1964, he determined to renew his musical language by returning to tonality, yet without abandoning a twentieth-century musical idiom. His Caprice Variations marks one of his first attempts to bring together the two polar opposite worlds of tonality and atonality. This one-and-a-half-hour-long work for solo violin is based on the theme from Paganini’s 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op.1, No. 24, and presents a wide range of technical challenges for the violinist. Since the piece is long, difficult to play, and now fifty years old, a performance guide to assist violinists is a useful contribution to the pedagogical literature. With a thorough analysis of the piece, and a consideration of both compositional and violin practice issues, as well as discussions with the original editor of the work and two violinists who have recorded it, ii my research will offer a complete performance guide for performers, advanced violin students, and violin teachers to assist them in achieving a deeper understanding of the work and a high level of artistic performance. -

A Study of Selected Piano Toccatas in the Twentieth Century: a Performance Guide Seon Hwa Song

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Study of Selected Piano Toccatas in the Twentieth Century: A Performance Guide Seon Hwa Song Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC A STUDY OF SELECTED PIANO TOCCATAS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE By SEON HWA SONG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the treatise of Seon Hwa Song defended on January 12, 2011. _________________________ Leonard Mastrogiacomo Professor Directing Treatise _________________________ Seth Beckman University Representative _________________________ Douglas Fisher Committee Member _________________________ Gregory Sauer Committee Member Approved: _________________________________ Leonard Mastrogiacomo, Professor and Coordinator of Keyboard Area _____________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Above all, I am eagerly grateful to God who let me meet precious people: great teachers, kind friends, and good mentors. With my immense admiration, I would like to express gratitude to my major professor Leonard Mastrogiacomo for his untiring encouragement and effort during my years of doctoral studies. His generosity and full support made me complete this degree. He has been a model of the ideal teacher who guides students with deep heart. Special thanks to my former teacher, Dr. Karyl Louwenaar for her inspiration and warm support. She led me in my first steps at Florida State University, and by sharing her faith in life has sustained my confidence in music. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1965-1966

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 1966 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation I " STMVINSKY tt.VlOW agon vam 7/re Boston Symphony SCHULLER 7 STUDIES ox THEMES of PAUL KLEE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA/ERICH lEINSDORf under Leinsdorf Leinsdorf expresses with great power the vivid colors of Schuller's Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Kiee and, in the same album, Stravinsky's ballet music from Agon. Forthe majorsinging roles in Menotti's dramatic cantata, The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi. Leinsdorf astutely selected George London, and Lili Chookasian, of whom the Chicago Daily Tribune has written, "Her voice has the Boston symphony ecich teinsooof / luminous tonal sheath that makes listening luxurious. menotti Also hear Chookasian in this same album, in songs from the death op the Bishop op BRSndlSI Schbnberg's Gurre-Lieder. In Dynagroove sound. Qeonoe ionoon • tilt choolusun s<:b6notec,/ou*«*--l(eoeo. sooq of the wooo-6ove ac^acm rca Victor fa @ The most trusted name in sound ^V V BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH LeinsDORF, Director Joseph Silverstein, Chairman of the Faculty Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Emeritus Louis Speyer, Assistant Director Victor Babin, Chairman of the Tanglewood Institute Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM Contemporary Music Activities Gunther Schuller, Head Roger Sessions, George Rochberg, and Donald Martino, Guest Teachers Paul Zukofsky, Fromm Teaching Fellow James Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Viola C Aliferis, Assistant Administrator The Berkshire Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. -

09 New Romanticisms, Complexities, Simplicities Student Copy

MSM CPP Survey EC 9. New… Romanticisms Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998) ''In the beginning, I composed in a distinct style,'' Mr. Schnittke said in an interview in 1988, ''but as I see it now, my personality was not coming through. More recently, I have used many different styles, and quotations from many periods of musical history, but my own voice comes through them clearly now.’' He continued, ''It is not just eclecticism for its own sake. When I use elements of, say, Baroque music,'' he added, ''sometimes I'm tweaking the listener. And sometimes I'm thinking about earlier music as a beautiful way of writing that has disappeared and will never come back; and in that sense, it has a tragic feeling for me. I see no conflict in being both serious and comic in the same piece. In fact, I cannot have one without the other.’' NY Times obituary. Concerto Grosso no. 1 (1977) “a play of three spheres: the Baroque, the Modern and the Banal” (AS) String Quartet no. 2 (1980) Concerto for Mixed Chorus (1984-1985) Wolfgang Rihm (*1952) String Quartet No. 5 (1981-1983) Vigilia (2006) Jagden und Formen (1995-2001) MSM CPP Survey EC Morton Feldman (1926-1987) Rothko Chapel (1971) ‘In 1972, Heinz-Klaus Metzger obstreperously asked Feldman whether his music constituted a “mourning epilogue to murdered Yiddishkeit in Europe and dying Yiddishkeit in America.” Feldman answered: It’s not true; but at the same time I think there’s an aspect of my attitude about being a composer that is mourning—say, for example, the death of art. -

Belatedness, and Sonata Structure in Rochberg's (Serial) Second

Trauma, Anxiety (of Influence), Belatedness, and Sonata Structure in Rochberg’s (Serial) Second Symphony Richard Lee University of Georgia Serialism is special to theorists and composers alike. For composer George Rochberg, doubly so: “I needed a language expressive and expansive enough to say what I had to. My war experience had etched itself deep into my soul.1 This essay is an exploration of Rochberg’s Second Symphony (1955–56)—“the first twelve-tone symphony composed by an American2— analyzed as a narrative of trauma, anxiety, and belatedness that emerges from the composer’s biography, his reliance on tradition (form), and his theorizing/deployment of serialism within a mid-20th-century compositional trend. Throughout this analysis, serialism acquires agency: it drives the following interpretation and has a capacity to act on (behalf of) Rochberg. Symphony No. 2 contains an array of thematic content that signifies trauma. The work stands as a response to World War II, therefore it makes sense to pin a biographical account of musical narrative to it. Rochberg was drafted in 1942 and his composition teacher, Hans Weisse, was driven out of Europe by the Nazi regime. In 1950, Rochberg went to Rome to study with Luigi Dallapiccola (known for his lyrical twelve-tone compositions), later telling Richard Dufallo that “one of the most powerful impulses toward twelve-tone, serialism, whatever you want to call it, was my reaction to my war experience which began to take over after the war.”3 1 George Rochberg, Five Lines, Four Spaces: The World of My Music, ed. Gene Rochberg and Richard Griscom (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 14. -

An Annotated Bibliography and Performance Commentary of The

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-1-2016 An Annotated Bibliography and Performance Commentary of the Works for Concert Band and Wind Orchestra by Composers Awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music 1993-2015, and a List of Their Works for Chamber Wind Ensemble Stephen Andrew Hunter University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Music Education Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Hunter, Stephen Andrew, "An Annotated Bibliography and Performance Commentary of the Works for Concert Band and Wind Orchestra by Composers Awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music 1993-2015, and a List of Their Works for Chamber Wind Ensemble" (2016). Dissertations. 333. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/333 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY OF THE WORKS FOR CONCERT BAND AND WIND ORCHESTRA BY COMPOSERS AWARDED THE PULITZER PRIZE IN MUSIC 1993-2015, AND A LIST OF THEIR WORKS FOR CHAMBER WIND ENSEMBLE by Stephen Andrew Hunter A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Catherine A. Rand, Committee Chair Associate Professor, School of Music ________________________________________________ Dr. -

Blair String Quartet

UPCOMING EVENTS GUEST ARTIST RECITAL • Monday, November 2, 2015: New Music Ensemble, Alan Shockley, director 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall $10/7 • • Thursday, November 12, 2015: University String Chamber, Joon Sung Jun, director 8:00pm Daniel Recital BLAIR Hall $10/7 • Friday, November 13, 2015: University String Quartet, Moni Simeonov, director 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall $10/7 STRING QUARTET • Saturday, November 14, 2015: Guest Artist Recital, Scordatura: Hannah Addario-Berry, cello 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall $10/7 • STEPHEN MIAHKY & CORNELIA HEARD, VIOLIN • Monday, November 16, 2015: Collegium Musicum, David Garrett, director 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall $10/ FREE JOHN KOCHANOWSKI, VIOLA • Friday, November 20, 2015: Bob Cole Conservatory Symphony, Johannes Müller-Stosch, conductor FELIX WANG, CELLO 8:00pm Carpenter Performing Arts Center Tickets $15/10 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2015 8:00PM GERALD R. DANIEL RECITAL HALL For upcoming events please call 562.985.7000 or visit: PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. This concert is funded in part by the INSTRUCTIONALLY RELATED ACTIVITIES FUNDS (IRA) provided by California State University, Long Beach. Keyboard Festival. The Blair Quartet has performed widely on National Public PROGRAM Radio and was featured for a number of years on a public television series called Recital Hall. The ensemble’s recordings have been praised internationally by such publications as Gramophone, Stereo Review, American Record Guide, and the Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 71, No. ..............................................1 Franz Josef Haydn BBC Music Magazine. They have recorded for labels such as Warner Brothers and Allegro (1732-1809) New World Records, and Naxos Records recently released The Blair Quartet’s Adagio recording of the String Quartets of Charles Ives. -

NY PHIL BIENNIAL AT-A-GLANCE COMPOSERS Daniel ACOSTA

NY PHIL BIENNIAL AT-A-GLANCE (as of April 10, 2014) COMPOSERS Daniel ACOSTA † Toshio HOSOKAWA John ADAMS HUANG Ruo Mark ANDRÉ Vijay IYER George BENJAMIN Michael JARRELL Luciano BERIO Chris KAPICA Oscar BETTISON György KURTÁG Pierre BOULEZ György LIGETI Ryan BROWN Franz LISZT André CAPLET Steven MACKEY Richard CARRICK Philippe MANOURY Elliott CARTER Bruno MANTOVANI Friedrich CERHA Colin MATTHEWS Elli CHOI † Eric NATHAN Nick CHOMOWICZ † Olga NEUWIRTH Ethan COHN † Jake O’BRIEN † Marc-André DALBAVIE Gérard PESSON Samantha DARRIS † Matthias PINTSCHER Zachary DETRICK § Milo PONIEWOZIK † Peter EÖTVÖS Eric PORETSKY † Morton FELDMAN Paola PRESTINI Daniel FELSENFELD Wolfgang RIHM Dai FUJIKURA Christopher ROUSE Julian GALESI §† Jay SCHWARTZ Helen GRIME Nina ŠENK HK GRUBER Johannes Maria STAUD Jack GULIELMETTI † Farah TASLIMA † Graydon HANSON † Galina USTVOLSKAYA Will HEALY † David WALLACE Michael HERSCH Julia WOLFE Heinz HOLLIGER Ryan WIGGLESWORTH Vito ZURAJ † denotes Very Young Composer of the New York Philharmonic § denotes Kaufman Music Center Special Music School High School student 2 Additional composers selected through the assistance of the EarShot National Orchestral Composition Discovery Network and from the American Composers Orchestra’s Underwood New Music Readings COMPOSERS’ COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN Austria Romania China Russia France Slovenia Germany Switzerland Hungary United Kingdom Italy United States Japan Venezuela WORLD PREMIERES Oscar BETTISON Threaded Madrigals (New York Philharmonic Commission) Zachary DETRICK (SMSHS student) Beyond There Julian GALESI (SMSHS student) Vote for Sheriff HUANG Ruo Chamber Concerto No. 2, The Lost Garden (World Premiere of chamber orchestra version) Michael HERSCH Of Sorrow Born: Seven Elegies (New York Philharmonic Commission) Chris KAPICA Fandanglish (New York Philharmonic Commission) Eric NATHAN As Above, So Below (New York Philharmonic Commission) Paola PRESTINI Eight Takes (New York Philharmonic Commission) Christopher ROUSE Symphony No.