An Audience-Based Approach in the Subtitling of Cultural Elements in Selected Iranian Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of Social-Spatial Exclusion and Identifying Its Factors Between Enqelab Street and College Crossroad in Tehran

The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication - TOJDAC August 2016 Special Edition STUDY OF SOCIAL-SPATIAL EXCLUSION AND IDENTIFYING ITS FACTORS BETWEEN ENQELAB STREET AND COLLEGE CROSSROAD IN TEHRAN Mahnaz Alimohammadi MSc of urban development planning, Faculty of Arts and Architecture, Islamic Azad University Central Tehran Branch Dr. Atusa Modiri Member of Scientific Board, Faculty of Arts and Architecture, Islamic Azad University Central Tehran Branch ABSTRACT Despite the fact that public spaces should be accessible for everyone, sometimes some of these spaces by the boundaries created by the owners or social groups, are only accessible for particular groups of society. Such boundaries in addition to reduction in the level of spaces’ communication, is a limiting factor in the entry and presence of different society classes in urban spaces; while increasing the presence and interaction of citizens with each other and interaction with space improves urban life. It can be said that most boundaries on public spaces with private and public ownership or symbolic ownership are all negative consequences of ownership and lead to social-spatial exclusion of other segments of society. This article aims to explain examples of social-spatial exclusion on Enqelab St. in Tehran. We used exploratory-qualitative approach in this research. By using survey and documents we collected data and finally analyzed the data through mapping, and provided a conclusion about influencing factors on social- spatial exclusion on the street, and thus -

Iran Case File (April 2019)

IRAN CASE FILE March 2020 RASANAH International Institute for Iranian Studies, Al-Takhassusi St. Sahafah, Riyadh Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. P.O. Box: 12275 | Zip code: 11473 Contact us [email protected] +966112166696 The Executive Summary .............................................................4 Internal Affairs .........................................................................7 The Ideological File ......................................................................... 8 I. Closing Shrines and Tombs ................................................................ 8 II. Opposition to the Decision Taken by Some People ............................. 8 III. Reaction of Clerics ........................................................................... 9 IV. Affiliations of Protesters .................................................................. 11 The Political File ............................................................................12 I. Khamenei Politicizes the Epidemic and Accuses Enemies of Creating the Virus to Target the Iranian Genome ..............................12 II. President Hassan Rouhani’s Slow Response in Taking Precautions to Face the Crisis ..................................................................................13 The Economic File ..........................................................................16 I. Forcible Passage of the Budget ...........................................................16 II. Exceptional Financial Measures to Combat the Coronavirus ............. 17 III. The -

Iranian and Turkish Food Cultures: a Comparison Through the Qualitative Research Method in Terms of Preparation, Distribution and Consumption

IJASOS- International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, Vol. I, Issue 3, December 2015 IRANIAN AND TURKISH FOOD CULTURES: A COMPARISON THROUGH THE QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHOD IN TERMS OF PREPARATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSUMPTION Gamze Gizem Avcıoğlu1 and Gürcan Şevket Avcıoğlu2 1 Res. Asst., Selçuk University, Turkey, [email protected] 2 Dr., Selçuk University, Turkey, [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this study is to make a comparative sociological analysis of Iranian and Turkish food cultures in terms of food preparation, distribution and consumption. Moreover, contribution is intended to be made to the field of applied food sociology. The research design carries features of a qualitative research. Of the qualitative research techniques, observation and interview form were used in the study. Research findings were obtained through observations made in Tehran, the capital city of Iran, and data were compiled by making interviews with people selected using the snowball sampling method. According to the results of observations and interviews, food habits in Iran tend to preserve their traditional characteristics. There are similarities rather than differences between Iran and Turkey in terms of eating habits and ways of eating. On the other hand, food culture is highly influenced by the food industry. Industrial food production, branding, packaging and wrapping are at an advanced level. Both Iran and Turkey are undergoing changes in terms of food as in other areas and coming under the influence of modernization. Food production, distribution and consumption systems or eating habits exhibit global trends. Although eating habits display global characteristics, they are always and in all communities based on local roots; in other words, the food culture is never separated from its cultural bonds. -

Historical Uses of Saffron: Identifying Potential New Avenues for Modern Research

id8484906 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ISSN : 0974 - 7508 Volume 7 Issue 4 NNaattuurraall PPrrAoon dIdnduuian ccJotutrnssal Trade Science Inc. Full Paper NPAIJ, 7(4), 2011 [174-180] Historical uses of saffron: Identifying potential new avenues for modern research S.Zeinab Mousavi1, S.Zahra Bathaie2* 1Faculty of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, (IRAN) 2Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, (IRAN) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 20th June, 2011 ; Accepted: 20th July, 2011 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Background: During the ancient times, saffron (Crocus sativus L.) had Saffron; many uses around the world; however, some of them were forgotten Iran; ’s uses came back into attention during throughout the history. But saffron Ancient medicine; the past few decades, when a new interest in natural active compounds Herbal medicine; arose. It is supposed that understanding different uses of saffron in past Traditional medicine. can help us in finding the best uses for today. Objective: Our objective was to review different uses of saffron throughout the history among different nations. Results: Saffron has been known since more than 3000 years ago by many nations. It was valued not only as a culinary condiment, but also as a dye, perfume and as a medicinal herb. Its medicinal uses ranged from eye problems to genitourinary and many other diseases in various cul- tures. It was also used as a tonic agent and antidepressant drug among many nations. Conclusion(s): Saffron has had many different uses such as being used as a food additive along with being a palliative agent for many human diseases. -

Banal Nationalism in Iran: Daily Re-Production of National and Religious Identity

Elhan / Banal Nationalism in Iran: Daily Re-Production of National and Religious Identity Banal Nationalism in Iran: Daily Re-Production of National and Religious Identity Nail Elhan* Öz: 1979 yılında yaşanan İran İslam Devrimi sonrasında İslamcı politikalar kurulan yeni rejimin hem iç hem de dış politikalarının temelini oluşturmuştur. Ancak milliyetçilik de göz ardı edilmemiş ve daha da ileri gidilerek Şii İslam ve İslam öncesi Pers kültürünün harmanlanması ile bir İranlılık kimliği yaratılmıştır. Bu kimlik devlet tarafından, Şii mitolojisi, İslam öncesi Pers kültürü, anti-emperyalizm, Üçüncü Dünyacılık ve anti-Siyonizm gibi ögelerle harmanlanmış ve çok etnikli İran toplumuna ortak bir aidiyet olarak sunulmuştur. Bu aidiyet olgusunun hem İran içinde hem de İran dışında cereyan eden olaylar üzerine inşa edildiği iddia edilebilir. Bunu yaparken, İran Devleti basılması kendi tekelinde olan banknotları, madeni paraları ve posta pullarını gündelik milliyeçiliğin aracı olarak kullanmış ve bu ‘banal’ yollar ile İranlılık duygusunun her gün yeniden üretilmesine katkı yapmıştır. Böylelikle, banknotlar, madeni paralar ve posta pulları gibi görsel semboller aracılığı ile devlet, kendi oluştur- duğu kimliği yine kendi içerisinde bulunan alt-ulusal kimliklerin bu resmi kimliğe saldırılarına karşı bir savunma aracı olarak banal milliyetçilik vasıtası ile kullanmış olmaktadır. Anahtar kelimeler: İran Devrimi, Banal Milliyetçilik, Şiilik, Fars Kimliği, Milli Kimlik. Abstract: After its 1979 revolution, Islamism became Iran’s main policy as regards its domestic and foreign affairs. However, nationalism continued to exist. After the revolution, the national identity of Iranianness based on Shii Islam and pre-Islamic Persian history was created. By merging Shii traditions, pre-Islamic Persian culture, anti-imperialism, Third Worldism, and anti-Zionism, this new identity was introduced as one of belonging. -

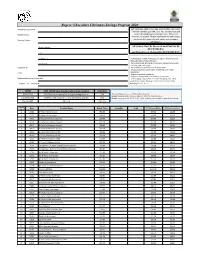

Rogers' Chocolates Christmas Savings Program 2020

Rogers' Chocolates Christmas Savings Program 2020 Company/Group Name: Call 1.800.663.2220 or 250.384.7021 to place your order, or fax this form to 250.384.5750. You can also scan and Contact Person: email it to [email protected]. If faxed or emailed, a customer service representative will contact Shipping Address: you to confirm your total and obtain your payment information. Street Address : All Orders Must Be Received and Paid For By DECEMBER 4, ` City : and Picked Up or Shipped By DECEMBER 11. Province : · If shipping to multiple addresses, our regular volume discount rates and freight charges will apply. Postal Code : · Not available with gift cards or previously discounted products. · Excludes taxes and freight. Telephone #: · Not available in combination with other offers. · Not applicable to custom orders. Please call us for more Email: information. · Subject to product availability. · Subject to change and/or cancellation at any time. Preferred delivery or pick-up date: · Free Shipping is applicable to Standard shipping only. Only applicable to orders shipping to destinations within Canada, □ Ground □ Air □ Pick-up @ excluding NL, NU, NT, YT. SPEND MAIL ORDER (also includes Factory Store Location) IN STORES $500-$999 10% Plus free shipping* to a single mailing address 10% *For qualifying orders over $500 (before discount) Ground shipping to BC, AB, SK, MB, ON, QC, NS, NB,PEI is free . $1,000-$5,000 25% Plus free shipping* to a single mailing address 20% Ground shipping to NL, NT, YT, NU, USA and international will be quoted -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

Tasting Banquet “Mazzeh”

Mazzeh - Tasting Banquet Two course meal - £16.95 per person Everything listed on this menu is served, eliminating the hassle of choosing! (Available for minimum of two persons ordering; no maximum) “Mazzeh” - First course Homous (V) (GF) (LF) Creamed chick peas, tahini, garlic, fresh lime juice, salt & extra virgin olive oil -and- Mast-o-Bademjan (V) (GF) Roasted aubergines, garlic, cumin, salt & cracked black pepper folded in yoghurt -and- Murgh Kabab (boneless chicken breast) (GF) (LF) Succulent cubes of chicken breast marinated in grated onion, saffron, salt, black pepper, extra virgin olive oil and lemon; cooked in clay oven on a skewer -and- Mixed Marinated Olives (GF) (LF) With onions, tomatoes, garlic, cracked black pepper, lemon juice, cumin, fennel and salt -and- Mahi Biryan (LF) River Cobbler (Asian fresh water fish), onion & carom seeds in tempura batter - deep fried -and- The above selection is served with our famous light, crisp and airy Flat Bread (LF) – one per person (V) Suitable for vegetarians; vegans please ask! (LF) Lactose free, without any dairy products (GF) Suitable for gluten free diet Our food is prepared in environment that contains nuts. If you have any special requirements, please ask.Please note that although most of my dishes still retain their original Persian names, these are all my own recipes and not Iranian anymore! I had to preserve these names, as mum called them by these names! Full a la carte menu is also available, please ask. “Khoraak-e-Asli” - Second course All served in individual pots, allowing -

Berdoll's Delicious Homemade Pecan Candies

! Berdoll’s Delicious Homemade Pecan Candies # 55…1 lb. Packages of Candied & Flavored Pecans $15.00 Choose an assortment of our mouth-watering pecan candies and flavored pecans! We make all 14 homemade flavors in our very own kitchens! AA – Milk Chocolate Caramel Pecan Clusters II – Dark Chocolate Caramel Pecan Clusters BB – Milk Chocolate Pecan Brittle JJ – Dark Chocolate Pecan Brittle CC- Milk Chocolate Pecans KK – Jalapeno Pecans EE – Roasted & Salted Pecans LL – White Chocolate Pecans FF – Cinnamon & Sugar Pecans MM – White Chocolate Caramel Pecan Clusters GG – Pecan Brittle UU – Honey Glazed Pecans HH – Dark Chocolate Pecans VV – Texas Mesquite Barbecue Show your Texas pride! # 556…1 lb. 3-Way Bag-TX $17.00 White Chocolate Pecans, Milk Chocolate Pecans, and Honey Glazed Pecans #101…1 lb. Texas Tin $20.00 Filled with White Chocolate Pecans, Milk Chocolate Pecans, and Honey Glazed Pecans # 201…2.5 lb. Texas Tin $45.00 Filled with Dark Chocolate Pecans, White Chocolate Pecans, Honey Glazed Pecans, Golden Pecan Halves, Milk Chocolate Caramel Pecan Clusters, Milk Chocolate Covered Pecan Brittle, and Cinnamon and Sugar Pecans. # 401…4.5 lb. Texas Tin $70.00 Double layer of Dark Chocolate Pecans, White Chocolate Pecans, Honey Glazed Pecans, Golden Pecan Halves, Milk Chocolate Caramel Clusters, Milk Chocolate Pecan Brittle, and Cinnamon and Sugar Pecans. Start crossing off your Holiday Gift List now! # 102…1 lb. Christmas Tin $20.00 White Chocolate Pecans, Milk Chocolate Pecans, and Honey Glazed Pecans # 202…2.5 lb. Christmas Tin $45.00 Dark Chocolate Pecans, White Chocolate Pecans, Honey Glazed Pecans, Golden Pecan Halves, Milk Chocolate Caramel Pecan Clusters, Milk Chocolate Covered Pecan Brittle, and Cinnamon and Sugar Pecans. -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Selection of Iranian Films 2020

In the Name of God PUBLISHER Farabi Cinema Foundation No. 59, Sie Tir Ave., Tehran 11358, Iran Management: Tel: +98 21 66708545 / 66705454 Fax: +98 21 66720750 [email protected] International Affairs: Tel: +98 21 66747826 / 66736840 Fax: +98 21 66728758 [email protected] / [email protected] http://en.fcf.ir Editor in Chief: Raed Faridzadeh Teamwork by: Mahsa Fariba, Samareh Khodarahmi, Elnaz Khoshdel, Mona Saheb, Tandis Tabatabaei. Graphics, Layout & Print: Alireza Kiaei A SELECTION OF IRANIAN FILMS 2020 CONTENTS Films 6 General Information 126 Awards 136 Statistics 148 Films Film Title P.N Film Title P.N A BALLAD FOR THE WHITE COW 6 NO PLACE FOR ANGELS 64 ABADAN 1160 8 PLUNDER 66 AMPHIBIOUS 10 PUFF PUFF PASS 68 ATABAI 12 RELY ON THE WIND 70 BANDAR BAND 14 RESET 72 BECAME BLOOD 16 RIOT DAY 74 BONE MARROW 18 THE NIGHT 76 BORN OF THE EARTH 20 THE BLACK CAT 78 CARELESS CRIME 22 THE BLUE GIRL 80 CINEMA SHAHRE GHESEH 24 THE ENEMIES 82 CROWS 26 THE FOURTH ROUND 84 DAY ZERO 28 THE GOOD, THE BAD,THE INDECENT 2 86 DROWN 30 THE GREAT LEAP 88 DROWNING IN HOLY WATER 32 THE INHERITANCE 90 EAR RINGED FISH 34 THE LADY 92 EXCELLENCY 36 THE MARRIAGE PROJECT 94 EXODUS 38 THE RAIN FALLS WHERE IT WILL 96 FATHERS 40 THE REVERSED PATH 98 FILICIDE 42 THE SKIN 100 FORSAKEN HOMES 44 THE SLAUGHTERHOUSE 102 I’M HERE 46 THE STORY OF FORUGH’S GIRL 104 I’M SCARED 48 THE SUN 106 IT’S WINTER 50 THE UNDERCOVER 108 KEEP QUIET SNAIL 52 THE WASTELAND 110 KILLER SPIDER 54 TITI 112 LIFE AMONG WAR FLAGS 56 TOOMAN 114 LUNAR ECLIPSE 58 WALKING WITH THE WIND 116 NARROW RED LINE 60 WALNUT TREE 118 NO CHOICE 62 A BALLAD FOR THE WHITE COW (Ghasideye Gaveh Sefid) Directed by: Behtash Sanaeeha Synopsis: Written by: Behtash Sanaeeha, Maryam Mina’s husband has just been executed Moghadam, Mehrdad Kouroshnia for murder.