Methodological Development for Harmonic Direction Finder Tracking in Salamanders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Diversity and Conservation Status of Amphibians in Madre De Dios, Southern Peru

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 4(1):14-29 Submitted: 18 December 2007; Accepted: 4 August 2008 SPECIES DIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF AMPHIBIANS IN MADRE DE DIOS, SOUTHERN PERU 1,2 3 4,5 RUDOLF VON MAY , KAREN SIU-TING , JENNIFER M. JACOBS , MARGARITA MEDINA- 3 6 3,7 1 MÜLLER , GIUSEPPE GAGLIARDI , LILY O. RODRÍGUEZ , AND MAUREEN A. DONNELLY 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, 11200 SW 8th Street, OE-167, Miami, Florida 33199, USA 2 Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] 3 Departamento de Herpetología, Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Avenida Arenales 1256, Lima 11, Perú 4 Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, California 94132, USA 5 Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118, USA 6 Departamento de Herpetología, Museo de Zoología de la Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana, Pebas 5ta cuadra, Iquitos, Perú 7 Programa de Desarrollo Rural Sostenible, Cooperación Técnica Alemana – GTZ, Calle Diecisiete 355, Lima 27, Perú ABSTRACT.—This study focuses on amphibian species diversity in the lowland Amazonian rainforest of southern Peru, and on the importance of protected and non-protected areas for maintaining amphibian assemblages in this region. We compared species lists from nine sites in the Madre de Dios region, five of which are in nationally recognized protected areas and four are outside the country’s protected area system. Los Amigos, occurring outside the protected area system, is the most species-rich locality included in our comparison. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

*For More Information, Please See

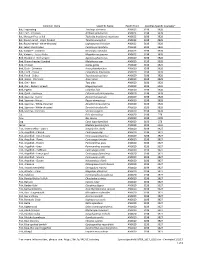

Common Name Scientific Name Health Point Specifies-Specific Course(s)* Bat, Frog-eating Trachops cirrhosus AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Fruit - Jamaican Artibeus jamaicensis AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Mexican Free-tailed Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Round-eared - stripe-headed Tonatia saurophila AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Round-eared - white-throated Lophostoma silvicolum AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Seba's short-tailed Carollia perspicillata AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Vampire - Common Desmodus rotundus AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Vampire - Lesser False Megaderma spasma AN0023 3198 3928 Bird, Blackbird - Red-winged Agelaius phoeniceus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Brown-headed Cowbird Molothurus ater AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Chicken Gallus gallus AN0020 3198 3529 Bird, Duck - Domestic Anas platyrhynchos AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Finch - House Carpodacus mexicanus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Finch - Zebra Taeniopygia guttata AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Goose - Domestic Anser anser AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Owl - Barn Tyto alba AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Owl - Eastern Screech Megascops asio AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Pigeon Columba livia AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Quail - Japanese Coturnix coturnix japonica AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - Harris' Zonotrichia querula AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - House Passer domesticus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - White-crowned Zonotrichia leucophrys AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - White-throated Zonotrichia albicollis AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Starling - Common Sturnus vulgaris AN0020 3198 3928 Cat Felis domesticus AN0020 3198 279 Cow Bos taurus -

1 Table S1. Temporal, Spectral, and Scaling Variables from Calls Of

Table S1. Temporal, spectral, and scaling variables from calls of poison frogs including phylogeny identifier (Phy ID), locality, call behavior, habit, temperature, size, number of recordings, multinote call features, units of repetition (UR), initial pulse-note, and middle pulse-note parameters. Analyzed Phy Locality Call Temp SVL (mm) Genus Species Latitude Longitude Habit recordings ID ID Behavior °C N ! SD N of ♂ Allobates algorei 60 El Tama 7.65375 -72.19137 concealed terrestrial 23.50 8 18.90 0.70 3 Allobates brunneus 37 Guimaraes -15.2667 -55.5311 -- terrestrial 26.50 1 16.13 0.00 1 Allobates caeruleodactylus 48 Borba -4.398593 -59.60251 exposed terrestrial 25.60 12 15.50 0.40 1 Allobates crombiei 52 Altamira -3.65 -52.38 concealed terrestrial 24.10 2 18.10 0.04 2 Allobates femoralis 43 ECY -0.633 -76.5 concealed terrestrial 25.60 20 23.58 1.27 6 Allobates femoralis 46 Porongaba -8.67 -72.78 exposed terrestrial 25.00 1 25.38 0.00 1 Allobates femoralis 44 Leticia -4.2153 -69.9406 exposed terrestrial 25.50 1 20.90 0.00 1 Allobates femoralis 40 Albergue -12.8773 -71.3865 exposed terrestrial 26.00 6 21.98 2.18 1 Allobates femoralis 41 CAmazonico -12.6 -70.08 exposed terrestrial 26.00 12 22.43 1.06 4 Allobates femoralis 45 El Palmar 8.333333 -61.66667 concealed terrestrial 24.00 27 25.50 0.76 1 Allobates granti 49 FG 3.62 -53.17 exposed terrestrial 24.60 8 16.15 0.55 1 Allobates humilis 59 San Ramon 8.8678 -70.4861 concealed terrestrial 19.50 -- 21.80 -- 1 Allobates insperatus 54 ECY -0.633 -76.4005 exposed terrestrial 24.60 18 16.64 0.93 7 Allobates aff. -

Amphibia, Anura, Dendrobatidae, Allobates Femoralis (Boulenger, 1884): First Confirmed Country Records, Venezuela

ISSN 1809-127X (online edition) © 2010 Check List and Authors Chec List Open Access | Freely available at www.checklist.org.br Journal of species lists and distribution N Allobates femoralis ISTRIBUTIO Amphibia, Anura, Dendrobatidae, D Venezuela (Boulenger, 1884): First confirmed country records, RAPHIC G César L. Barrio-Amorós and Juan Carlos Santos 2 EO 1* G N O 1 Fundación Andígena, [email protected] postal 210, 5101-A. Mérida, Venezuela. OTES 2 University of Texas at Austin, Integrative Biology. 1 University Station C0930. Austin, TX 78705, USA. N * Corresponding author E-mail: Abstract: Allobates femoralis analized advertisement calls taken at two Venezuelan localities. The presence of the dendrobatid frog in Venezuela is herein confirmed though recorded and Allobates femoralis is a common dendrobatid frog widely distributed throughout the Amazon and Guianas in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, French Guiana, series of four notes at Las Claritas is 0.52 sec; the dominant Suriname and Guyana (Lötters et al. frequency is at 2954 Hz and the fundamental frequency is error, based on KU (Natural History 2007). Museum, The firstUniversity report of this species from Venezuela (Duellman 1997) was in was later recognized as Ameerega guayanensis (Barrio- Amorósof Kansas, 2004). Lawrence, Ameerega Kansas, guayanensisUSA) 167335. was This describedspecimen 2004).for populations Today however, of eastern this Venezuelataxon validity and is some questionable authors considered it as valid (Schulte 1999; Barrio-Amorós A.(J.C. (picta) Santos guayanensis unpublished because data). itSince is theno validnomenclatural available act was yet performed, we herein use the combinationAllobates femoralis was removed from the Venezuelan checklist name for those populations. -

Do Natural Differences in Acoustic Signals Really Interfere in Conspecific Recognition in the Pan-Amazonian Frog Allobates Femoralis?

Do natural differences in acoustic signals really interfere in conspecific recognition in the pan-Amazonian frog Allobates femoralis? Luciana K. Erdtmann1), Pedro I. Simões, Ana Carolina Mello & Albertina P. Lima (Coordenação de Pesquisas em Ecologia, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Avenida André Araújo 2936, Cx. Postal 478, Aleixo, Manaus, AM 69060-001, Brazil) (Accepted: 28 February 2011) Summary The call of the pan-Amazonian frog Allobates femoralis shows wide geographical variation, and males show a stereotyped and conspicuous phonotactic response to playback of conspe- cific calls. We evaluated the capacity of males of A. femoralis and a closely related species A. hodli to respond aggressively to natural conspecific and heterospecific calls varying in number of notes, by means of field playback experiments performed at two sites in the Brazil- ian Amazon. The first site, Cachoeira do Jirau (Porto Velho, Rondônia), is a parapatric con- tact zone between A. femoralis that use 4-note calls, and A. hodli with 2-note calls, where we performed cross-playbacks in both focal populations. The second site, the Reserva Florestal Adolpho Ducke (Manaus, Amazonas), contained only A. femoralis with 4-note calls. There, we broadcast natural stimuli of 2-note A. hodli, 3-note and 4-note A. femoralis, and 6-note A. myersi. We found that the phonotactic behaviour of A. femoralis and A. hodli males did not differ toward conspecific and heterospecific stimuli, even in parapatry. Our results indi- cated that the evolutionary rates of call design and call perception are different, because the geographical variation in calls was not accompanied by variation in the males’ aggressive behaviour. -

Acoustic Interference and Recognition Space Within a Complex Assemblage of Dendrobatid Frogs

Acoustic interference and recognition space within a complex assemblage of dendrobatid frogs Adolfo Amézquitaa,1, Sandra Victoria Flechasa, Albertina Pimentel Limab, Herbert Gasserc, and Walter Hödlc aDepartment of Biological Sciences, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, AA 4976, Colombia; bInstituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, CEP 69060-001, Manaus, Brazil; and cDepartment of Evolutionary Biology, Institute of Zoology, University of Vienna, A-1090 Vienna, Austria Edited by Michael J. Ryan, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and accepted by the Editorial Board September 1, 2011 (received for review March 24, 2011) In species-rich assemblages of acoustically communicating animals, insects (22), and frogs (23, 24). Because heterospecific sounds may heterospecific sounds may constrain not only the evolution of sig- represent noise that interferes with signal detection (25, 26), the nal traits but also the much less-studied signal-processing mecha- communication systems should reveal adaptations that reduce its nisms that define the recognition space of a signal. To test the effects. To date, most research to validate this idea has been hypothesis that the recognition space is optimally designed, i.e., conducted on the characteristics of the signals or on the pattern of that it is narrower toward the species that represent the higher signaling activity (27, 28), but compelling evidence suggests that potential for acoustic interference, we studied an acoustic assem- recognition systems can evolve without concomitant variation in blage of 10 diurnally active frog species. We characterized their the signals (20, 29). We present here a manipulative study on a calls, estimated pairwise correlations in calling activity, and, to species-rich assemblage of diurnal frogs to test the general model the recognition spaces of five species, conducted playback hypothesis that the recognition space is shaped in a way that experiments with 577 synthetic signals on 531 males. -

A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname

Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen 67 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed RAP (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Bulletin of Biological Assessment 67 Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel : +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover photos: The RAP team surveyed the Grensgebergte Mountains and Upper Palumeu Watershed, as well as the Middle Palumeu River and Kasikasima Mountains visible here. Freshwater resources originating here are vital for all of Suriname. (T. Larsen) Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium cf. taylori) lay their -

Ecology and Evolution of Phytotelm- Jreeding Anurans

* ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF PHYTOTELM- JREEDING ANURANS Richard M. Lehtinen Editor MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS I--- - MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 193 Ann Ahr, November, 2004 PUBLICATIONS OF THE MUSEUM OF ZQOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 192 J. B. BURCII,Editot* Ku1.1: SI.EFANOAND JANICEPAPPAS, Assistant Editoras The publications of the Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, consist primarily of two series-the Miscellaneous P~rhlicationsand the Occasional Papers. Both serics were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. Occasionally the Museum publishes contributions outside of thesc series; beginning in 1990 these are titled Special Publications and are numbered. All s~tbmitledmanuscripts to any of the Museum's publications receive external review. The Occasiontrl Papers, begun in 1913, sellie as a mcdium for original studies based prii~cipallyupon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Mi.scelluneous Puhlicutions, initiated in 1916, include monographic studies, papers on field and museum techniques, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, and are publislled separately. It is not intended that they bc grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Amphibians, Fishes, Insects, Mollusks, and other topics is avail- able. Address inquiries to Publications, Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48 109-1079. -

Taxonomic Checklist of Amphibian Species Listed in the CITES

CoP17 Doc. 81.1 Annex 5 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) Taxonomic Checklist of Amphibian Species listed in the CITES Appendices and the Annexes of EC Regulation 338/97 Species information extracted from FROST, D. R. (2015) "Amphibian Species of the World, an online Reference" V. 6.0 (as of May 2015) Copyright © 1998-2015, Darrel Frost and TheAmericanMuseum of Natural History. All Rights Reserved. Additional comments included by the Nomenclature Specialist of the CITES Animals Committee (indicated by "NC comment") Reproduction for commercial purposes prohibited. CoP17 Doc. 81.1 Annex 5 - p. 1 Amphibian Species covered by this Checklist listed by listed by CITES EC- as well as Family Species Regulation EC 338/97 Regulation only 338/97 ANURA Aromobatidae Allobates femoralis X Aromobatidae Allobates hodli X Aromobatidae Allobates myersi X Aromobatidae Allobates zaparo X Aromobatidae Anomaloglossus rufulus X Bufonidae Altiphrynoides malcolmi X Bufonidae Altiphrynoides osgoodi X Bufonidae Amietophrynus channingi X Bufonidae Amietophrynus superciliaris X Bufonidae Atelopus zeteki X Bufonidae Incilius periglenes X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides asperginis X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides cryptus X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides frontierei X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides laevis X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides laticeps X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides minutus X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides paulae X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides poyntoni X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides pseudotornieri X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides tornieri X Bufonidae Nectophrynoides vestergaardi -

Decoupled Evolution Between Senders and Receivers in the Neotropical Allobates Femoralis Frog Complex

RESEARCH ARTICLE Decoupled Evolution between Senders and Receivers in the Neotropical Allobates femoralis Frog Complex Mileidy Betancourth-Cundar1*, Albertina P. Lima2, Walter Hödl3, Adolfo Amézquita1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Universidad de Los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia, 2 Coordenaçãode Pesquisas em Biodiversidade, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil, 3 Department of Integrative Zoology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria a11111 * [email protected] Abstract During acoustic communication, an audible message is transmitted from a sender to a OPEN ACCESS receiver, often producing changes in behavior. In a system where evolutionary changes of the sender do not result in a concomitant adjustment in the receiver, communication and Citation: Betancourth-Cundar M, Lima AP, Hödl W, species recognition could fail. However, the possibility of an evolutionary decoupling Amézquita A (2016) Decoupled Evolution between Senders and Receivers in the Neotropical Allobates between sender and receiver has rarely been studied. Frog populations in the Allobates femoralis Frog Complex. PLoS ONE 11(6): femoralis cryptic species complex are known for their extensive morphological, genetic and e0155929. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155929 acoustic variation. We hypothesized that geographic variation in acoustic signals of A. Editor: William J. Etges, University of Arkansas, femoralis was correlated with geographic changes in communication through changes in UNITED STATES male-male recognition. To test -

Anura: Aromobatidae) from the Type Locality (Cachoeira Do Espelho), Xingu River, Brazil

Zootaxa 3475: 86–88 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press Correspondence ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D975CEA0-9884-4AF6-BB33-73B76983BABD Advertisement call and colour in life of Allobates crombiei (Morales) “2000” [2002] (Anura: Aromobatidae) from the type Locality (Cachoeira do Espelho), Xingu River, Brazil ALBERTINA P. LIMA1, LUCIANA K. ERDTMANN1 & ADOLFO AMÉZQUITA2 1Coordenação de Biodiversidade, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia Av. André Araújo, 2936, 69083-000, Manaus, AM, Brasil 2Department of Biological Sciences, Universidad de los Andes, AA 4976, Bogotá, Colombia 1Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Allobates crombiei was described by Morales, “2000” [2002] based on specimens collected by Ronald I. Crombie from Cachoeira do Espelho, on the right bank of the Xingu River, Pará State, Brazil. The original description was short and did not include the call or colour in life. Rodrigues & Caramaschi (2004) suggested that the taxonomic status of this species need be clarified. We are confident that the species collected and recorded by us is Allobates crombiei (Morales) “2000” [2002] because this is the only species of Allobates found calling in forest near Cachoeira do Espelho, and the character diagnosis in preserved specimens is similar, except that, based on preserved specimens, Morales (2002) considered the ventrolateral and the oblique lateral stripes to be absent. This may be because they are imperceptible in preserved specimens. However, unlike recent authors, Morales (2002) also considered the oblique lateral stripe to be absent in Allobates brunneus, Allobates gasconi and Allobates ornatus, in which he illustrated diffuse spots.