Conflicts, Acceptance Problems and Participative Policies in the National Parks of the French Alps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moûtiers Doucy Station Valmorel

MOÛTIERS T1 DOUCY STATION T2 VALMOREL Moûtiers Gare routière – SNCF La Région Du 6 juillet 2019 vous transporte au 31 août 2019 T1 Saint Oyen T2 Aigueblanche Centre Centre T1 Doucy (Ecole) T2 Le Bois Saint Hélène / Les Cours T1 Doucy-Station Centre Le Sappey / Les Carlines Oice du tourisme T2 Aigueblanche Eau Rousse Crey / Les Emptes T2 Les Avanchers Le Fey Dessous Chef lieu Le Pré T2 Valmorel Bourg Morel Crève Cœur TARIFS Guichet En ligne * Aller simple (AS) adulte 13,40€ 13,40€ Aller simple 11,40€ 10,00€ moins de 26 ans et saisonniers Aller-retour (AR) adulte 24,00€ 22,70€ Aller-retour 22,70€ 20,00€ moins de 26 ans / saisonniers Abonnement 67,00€ 67,00€ *Frais de réservation : 1,00€ (+1,90 € en cas d’envoi postal) Tourisme © Christian Martelet/Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes INFORMATIONS ET RÉSERVATIONS : vente-bellesavoieexpress.fr DOUCY STATION MOÛTIERS DOUCY STATION T1 VALMOREL T1 VALMOREL MOÛTIERS N’oubliez pas de vous reporter aux renvois ci-dessous N’oubliez pas de vous reporter aux renvois ci-dessous T2 T2 Les jours de circulation des services sont abrégés comme suit : LUN : lundi Sam Sam Sam Sam Sam Dim Sam Sam Sam SamMAR : mardiSam, Dim 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 MER 1 : mercredi 1 2 JEU : jeudi T1 DOUCY STATION MOÛTIERS VEN : vendredi T1 MOÛTIERS DOUCY STATION SAM : samedi DIM : dimanche MOÛTIERS DOUCY Station 9.45 11.40 15.15 - - - 13.30 15.50 18.30 - - - Gare routière Mobilité DOUCY Bourg 10.00 11.55 15.30 La- ligne est accessible- aux- SAINT-OYEN 13.40 16.00 18.40 - - - personnes à mobilité réduite SAINT-OYEN 10.10 12.05 15.40 le samedi- uniquement.- - Réservation obligatoire le jeudi DOUCY Bourg 13.50 16.10 18.50 - - - avant 17h au 09 70 83 90 73 MOÛTIERS 10.20 12.15 15.50 - - - DOUCY Station 14.05 16.25 19.05 - - - Gare routière Attention Les horaires sont succeptibles T2 MOÛTIERS VALMOREL T2 VALMOREL MOÛTIERS d’être modifiés, pensez à vérifier les informations avant MOÛTIERS VALMOREL - - - 9.45votre voyage.15.20 Les horaires16.10 sont - - - 9.00 14.30 15.25 accesssibles dans la limite Gare routière des places disponibles. -

Guide Pratique

Guide pratique 2020/2021 des paroisses du doyenné de Moûtiers Sainte-Marie Madeleine d’Aigueblanche Saint-Pierre Tarentaise – Cathédrale Notre-Dame des Belleville Saint-Martin Val Vanoise Saint-François de Sales Val Vanoise Guide pratique du doyenné de Moûtiers CE GUIDE A ÉTÉ CONÇU ET RÉALISÉ PAR L’ÉQUIPE COMMUNICATION DES PAROISSES DU DOYENNÉ EN COLLABORATION AVEC Bayard Service Tél. 04 79 26 28 21 RÉALISATION TECHNIQUE Bayard Service Centre-Alpes - Grand Sud Savoie Technolac - Allée Lac de Garde CS 20308 - 73 377 Le Bourget-du-Lac Cedex [email protected] - www.bayard-service.com CONCEPTION GRAPHIQUE : KARINE MOULIN - ASSISTANT D’ÉDITION ET MISE EN PAGE : FRANCIS PONCET IMPRIMERIE Gutenberg - 74960 Meythet - Dépôt légal : à parution - CREDIT PHOTOS : © Paroisse de Moûtiers , diocèses de Savoie sauf mention contraire Éditorial Découvrir par soi-même des lieux moins connus... Avant de partir en vacances, j’aime me plonger dans des guides de la région où je me rends et aussi découvrir des sites internet qui sont généralement bien faits. Mon objectif est de ne pas rater des lieux et des événements importants. Sur place, j’ai aussi la possibilité de flâner et de découvrir par moi-même des lieux moins connus. Nous vous proposons avec ce guide paroissial et aussi avec nos sites internet actuellement en construction de pouvoir voyager avec nous et de vivre une belle aventure. L’Église a pour vocation de permettre de découvrir le Christ Vivant, Ressuscité, chemin qui conduit à Dieu. Vous qui vous repérez facilement dans nos cinq paroisses, vous trouverez des renseignements mis à jour. -

Votre Guide Mobilité Your Public Transport Guide

Votre guide mobilité Your public transport guide HIVER WINTER 2019-2020 Tous les horaires : du 14 décembre 2019 au 24 avril 2020 All schedules: from 14th December 2019 to 24th April 2020 Se la rouler douce… en Haute Maurienne Vanoise Travel easy... in Haute Maurienne Vanoise Nous mettons à votre service des lignes de trans- We provide you with public transport services so port en commun, pour vous permettre de vous you can explore all of our beautiful land. déplacer sur tout notre beau territoire. All the information you need for a great stay is L’ensemble des informations nécessaires pour available in this guide. un séjour agréable est compilé dans ce guide. If you require further information, we would be Si toutefois, vous avez besoin de précisions, nous delighted to answer your questions on: serons ravis de vous répondre au 04 79 05 99 06. +33 (0)4 79 05 99 06. L’ensemble de ces informations se trouve For more informations please go on www.haute- sur le site internet www.haute-maurienne- maurienne-vanoise.com/hiver/haute-maurienne- vanoise.com/hiver/haute-maurienne-vanoise/ vanoise/destination/se-deplacer-en-hmv/ destination/se-deplacer-en-hmv/ ou en flashant or scan the QR code above. le QR Code ci-contre : Informations générales 3 Tarifs et conditions de vente 4 Saint-André - Modane 8 Le Bourget - La Norma 9 Modane - Valfréjus (le samedi) 10 Modane - La Norma (le samedi) 11 Valfréjus - Modane - La Norma 12 SUMMARY SOMMAIRE M11 Modane - Aussois (le samedi) 15 M11 Modane - Aussois - Val Cenis Lanslebourg • Le dimanche : du 22 déc. -

CAHIER D'architecture HAUTE Maurienne

CAHIER D’ARCHITECTURE Haute MaurieNNE / VANOISE Toute rénovation ou construction nouvelle va marquer l’espace de façon durable. Des paysages de caractère Chaque paysage possède un trait distinctif ou, mieux, une personnalité susceptible de susciter familiarité ou étrangeté. La Haute Maurienne présente un habitat très groupé en fond de vallée, le long de l’Arc et des voies de passage (col du Mont-Cenis, Petit Mont-Cenis et Iseran) pour libérer les prés de cultures et de fauche. Au-delà, le paysage est étagé, déterminé en cela par le relief et l’activité humaine : torrents, cultures, forêts, alpages, sommets, Parc national de la Vanoise. Depuis la fin du XXe siècle, l’usage de la montagne pour les sports d’hiver a bouleversé l’ancienne polarité et la montagne est désormais parcourue été comme hiver. Pour plus de précisions, se référer page 6 du document général. m k l j km N 0 1 Cartes IGN au 1 : 25 000 n° 3432 ET, 3532 OT, 3531 ET, 3532 ET, 3433 ET, 3534 OT et 3633 ET réduites à l’échelle du 1 : 150 000 © IGN - Paris - autorisation n° 9100 Reproduction interdite 46 Voilà nos paysages que des générations ont soigneusement construits et entretenus par leur savoir-faire, pour mieux y vivre. 10. Pays de Modane 12. Pays du Mont-Cenis Cette entité transversale marque le seuil de la Haute Maurienne. Elle est La haute vallée de l’Arc, de Lanslebourg à Lanslevillard, constitue un cadrée en rive droite (adret) par les sommets majestueux et glaciers du second seuil, délimité à l’amont par le col de La Madeleine. -

Foncier Agricole

SCOT TARENTAISE Schéma de COhérence Territoriale VANOISE TARENTAISE Assemblée du Pays UNE VALLÉE DURABLE POUR TOUS SCoT Tarentaise Diagnostic foncier agricole Document contributif pour le SCoT – juillet 2013 – n° 3 2 Contexte du diagnostic agricole Les particularités géographiques de la L’objectif du diagnostic foncier agricole vallée de la Tarentaise, notamment l’alti- est de répondre à plusieurs questions : tude et la topographie, structurent le fon- cier agricole. — Quelle est la situation de l’agriculture en Tarentaise aujourd’hui ? L’espace est extrêmement contraint : 3 % — Quels sont ses atouts et ses fai- du territoire est à la fois à une altitude in- blesses ? férieure à 1 500 m et présente une pente — Quels sont ses besoins en foncier ? modérée (moins de 25 %) ! Ces 3 % sont — Où est localisé le foncier stratégique déjà fortement occupés par les infrastruc- pour l’agriculture ? tures et l’urbanisation et sont convoités — Peut-on mieux valoriser certains sec- pour de multiples usages dont l’activité teurs ? agricole. L’agriculture couvre aujourd’hui 40 % du territoire. Elle est encore bien présente et structurée, mais fortement dépendante du foncier. Elle est, par ailleurs, une com- posante essentielle du cadre de vie pour les habitants et touristes. Vallée des Glaciers – Bourg-Saint-Maurice Le Schéma de cohérence territoriale (SCoT), en tant qu’outil de planification, devra se positionner sur l’usage du fon- cier. Pour cela, une bonne connaissance de l’activité agricole et des enjeux liés au foncier est indispensable. L’étude sur le foncier agricole est une des approches thématiques réalisée préala- blement à l’élaboration du Projet d’Amé- nagement et de Développement Durable du SCoT. -

Annexe 2 Listes Communes Isolées AAC Octobre 2019

ANNEXE 2 Listes communes de montagne hors unité urbaine • AIGUEBELETTE-LE-LAC (73610) • AIME-LA –PLAGNE (73210) • AILLON-LE-JEUNE (73340) • AILLON-LE-VIEUX (73340) • AITON (73220) • ALBIEZ-LE-JEUNE (73300) • ALBIEZ-MONTROND (73300) • ALLONDAZ (73200) • APREMONT (73190) • ARGENTINE (73220) • ARITH (73340) • ARVILLARD (73110) • ATTIGNAT-ONCIN (73610) • AUSSOIS (73500) • AVRESSIEUX (73240) • AVRIEUX (73500) • AYN (73470) • BEAUFORT (73270) • BELLECOMBE-EN-BAUGES (73340) • BELMONT-TRAMONET (73330) • BESSANS (73480) • BILLIEME (73170) • BONNEVAL-SUR-ARC (73480) • BONVILLARD (73460) • BONVILLARET (73220) • BOURDEAU (73370) • BOURGET-EN-HUILE (73110) • BOZEL (73350) • BRIDES-LES-BAINS (73570) • CEVINS (73730) • CHAMOUX-SUR-GELON (73390) • CHAMP-LAURENT (73390) • CHAMPAGNEUX (73240) • CHAMPAGNY-EN-VANOISE (73350) • CLERY (73460) • COHENNOZ (73590) • CONJUX (73310) • CORBEL (73160) • COURCHEVEL (73120) • CREST-VOLAND (73590) • CURIENNE (73190) • DOUCY-EN-BAUGES (73630) • DULLIN (73610) • ECOLE (73630) • ENTRELACS (73410) • ENTREMONT-LE-VIEUX (73670) • EPIERRE (73220) • ESSERTS-BLAY (73540) • FEISSONS-SUR-SALINS (73350) • FLUMET (73590) • FONTCOUVERTE-LA TOUSSUIRE (73300) • FRENEY (73500) • FRETERIVE (73250) • GERBAIX (73470) Mis à jour octobre 2019 ANNEXE 2 • GRAND AIGUEBLANCHE (73260) • GRESY-SUR-ISERE (73460) • HAUTECOUR (73600) • HAUTELUCE (73620) • HAUTEVILLE (73390) • JARRIER (73300) • JARSY (73630) • JONGIEUX (73170) • LA BAUCHE (73360) • LA BIOLLE (73410) • LA CHAPELLE (73660) • LA CHAPELLE-BLANCHE (73110) • LA CHAPELLE-DU-MONT-DU-CHAT (73370) -

Projet D'arrêté

PRÉFET DE LA SAVOIE Direction Départementale des Territoires Service Sécurité Risques Unité Risques Arrêté préfectoral DDT/SSR/unité risques n° 2015-2288 prolongeant le délai de prescription du Plan de Prévention des Risques d’Inondation de l’Arc sur les communes de : Bramans, Sollières-Sardières, Termignon, Lanslebourg Mont-Cenis, Lanslevillard, Bessans et Bonneval sur Arc Le Préfet de la Savoie, Chevalier de l’Ordre National de la Légion d'honneur VU le code de l’environnement, VU le code de l’urbanisme, VU le code de la construction et de l’habitat, VU le décret n° 95-1089 du 5 octobre 1995 modifié relatif aux plans de prévention des risques naturels prévisibles, VU l'arrêté préfectoral du 26 décembre 2012 prescrivant la réalisation d'un Plan de Prévention des Risques d'Inondation de l'Arc sur les parties des territoires des communes de Bramans, Sollières-Sardières, Termignon, Lanslebourg Mont-Cenis, Lanslevillard, Bessans et Bonneval sur Arc, CONSIDERANT que le PPRI ne pourra pas être approuvé dans les délais impartis, soit pour le 26 décembre 2015, et qu’un délai supplémentaire est nécessaire pour mener à bien la procédure engagée, SUR proposition de Monsieur le directeur départemental des territoires de la Savoie, ARRETE Article 1 e r : Le délai d’élaboration du plan de prévention des risques d'inondation (PPRI) de l'Arc sur les parties des territoires des communes de Bramans, Sollières-Sardières, Termignon, Lanslebourg Mont-Cenis, Lanslevillard, Bessans et Bonneval sur Arc, prescrit par arrêté du 26 décembre 2012, et devant être finalisé dans les 3 ans après sa prescription conformément à l’article R562-2 du code de l’environnement, est prolongé de 18 mois, soit jusqu’au 26 juin 2017. -

Plan De Prévention Des Risques Inondation De L'arc De Bramans À Bonneval Sur Arc (Plan Annexé À L'arrêté Préfectoral De Prescription)

MINISTERE DE L’ECOLOGIE, DU DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE ET DE L’ENERGIE Direction départementale des Territoires de la Savoie Service Sécurité Risques Unité Risques Plan de Prévention des Risques Inondation de l’Arc Tronçon de Bramans à Bonneval sur Arc (7 communes) I.1 – Note de présentation Direction Départementale des Territoires de la Savoie - L'Adret - 1 rue des Cévennes - 73011 CHAMBERY Cedex Standard : 04 .79.71.73.73 - Télécopie : 04.79.71.73.00 - [email protected] www.savoie.gouv.fr Sommaire Sommaire .................................................................................................................. 1 Chapitre 1. Les plans de préventions des risques naturels : contexte règlementaire et doctrine ............................................................................................................... 3 1.1. POURQUOI DES PPRI EN FRANCE ? .......................................................................... 3 1.2. UN CONTEXTE JURIDIQUE ........................................................................................ 4 1.3. LA DOCTRINE RELATIVE AU RISQUE INONDATION .................................................. 6 1.4. OBJECTIFS DU PPRI ................................................................................................... 7 1.5. CONTENU DU DOSSIER DE PPRI ............................................................................... 8 1.6. LA PROCEDURE ......................................................................................................... 9 1.7. INCIDENCES DU PPRI ............................................................................................. -

Travaux Scientifiques Du Parc National De La Vanoise

MINISTÈRE DÉLÉGUÉ ISSN 0180-961 X CHARGÉ DE L'ENVIRONNEMENT DIRECTION DE LA PROTECTION DE LA NATURE Travaux scientifiques du Parc National de la Vanoise Recueillis et publiés sous la direction de C. PAIRAUDEAU Directeur du Parc National Tome XVI 1988 Cahiers du Parc National de la Vanoise 135, rue du Docteur-Julliand B.P. 705, 73007 CHAMBÉRY Cedex (France) ISSN 0180-961 X Parc National de la Vanoise, Chambéry, France, 1988 COMPOSITION DU COMITE SCIENTIFIQUE DU PARC NATIONAL DE LA VANOISE Président honoraire : M. Philippe TRAYNARD, Président honoraire de l'Institut National Polytechnique de Gre- noble. Président: M. Denys PRADELLE, Architecte-Urbaniste, Chambéry. Viœ-Présidents : M. Philippe LEBRETON, Professeur à l'Université Claude Bernard Lyon l. M. André PALLUEL-GUILLARD, Maître Assistant à l'Université de Savoie, Chambéry. Membres du Comité: M. Roger BUVAT, Membre de l'Académie des Sciences, Professeur Honoraire à l'Univer- site de Marseille. M. Marc BOYER, Maître de Conférence à l'Université Lyon 2. M. Raymond CAMPAN, Professeur à l'Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse. M. Yves CARTON, Maître de Recherches, C.N.R.S., Gif-sur-Yvette. M. Louis CHABERT, Professeur à l'Université Lyon 2. M. Charles DEGRANGE, Professeur à l'Université Joseph Fourier, Grenoble. M. René DELPECH, Professeur honoraire à l'Institut National Agronomique Paris-Gri- gnon. M. Philippe DREUX, Professeur à l'Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris. M. Bernard FANDRE, Administrateur Délégué du C.N.R.S., Grenoble. R.P. Robert FRITSCH, Président de la Société d"Histoire Naturelle de la Savoie. M. Louis Jean CACHET, Conservateur Adjoint au Musée Savoisien, Chambéry. -

Concours Départemental Des Villes, Villages Et Maisons Fleuris

CONCOURS DÉPARTEMENTAL DES VILLES, VILLAGES ET MAISONS FLEURIS PALMARÈS 2019 LA SAVOIE « Département fleuri » 2 Le Département s’enorgueillit de nouveau de se voir décerner le « Label Département Fleuri », par le Conseil National des Villes et Villages Fleuris, pour une durée de 5 ans. Le fleurissement contribue aux actions menées par le Département dans les collectivités locales en faveur de la gestion du foncier, la qualité des eaux, la protection des paysages d’exception, la qualité de l’environnement. A cet égard, depuis plus de 20 ans le Département s’est engagé dans une politique environnementale très ambitieuse dont le fleurissement est un des volets. 2019 SEPTEMBRE LA SAVOIE DÉPARTEMENT FLEURI CANDIDATURE AU RENOUVELLEMENT DU LABEL DÉPARTEMENT FLEURI Le concours départemental des villes, villages et maisons fleuris Le Département de la Savoie a Qui peut participer ? 4 donné délégation à l’Agence Alpine Toutes les communes de Savoie ainsi des Territoires pour l’organisation que les particuliers dont la commune du Concours des villes, villages et a fait acte de candidature. maisons fleuris avec pour objectif d’améliorer la qualité de vie des Comment s’inscrire ? habitants et renforcer l’attractivité Le bulletin d’inscription est adressé du territoire. La démarche consiste à toutes les communes de Savoie à accompagner et à distinguer les accompagné de son règlement actions des collectivités locales et fin avril. L’inscription est payante des particuliers qui contribuent à la et obligatoire pour permettre aux mise en valeur de nos paysages, de particuliers de participer au concours. nos espaces publics dans le respect L’inscription doit impérativement être de l’environnement et à récompenser retournée avant le 31 mai. -

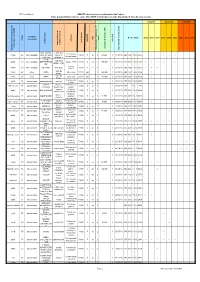

ERP/IOP Dont La Mise En Conformité a Fait L'objet D'une Programmation Dans Le Cadre D'un Ad'ap Instruit Dans Un Autre Département (Lieu Du Siège Social)

DDT de la Savoie ERP/IOP dont la mise en conformité a fait l'objet d'une programmation dans le cadre d'un Ad'AP instruit dans un autre département (lieu du siège social) période1 période2 période3 commune N° de l'adap 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 concernée type ans) n°dept adresse avis (f/d) catégorie code postal pétitionnaire l'établissement dénomination de instructeur de l'Ad'AP montant demontant travaux (HT) Nb périodesNb (1 période = 3 date signature arrêté préfet département siègedu social, Etat - SGAR - centre des 1221 avenue rhone 69 aime la plagne ERP de l'Etat finances 73210 5 w 3 30 820 f 14/01/16 069 123 15 O 0216 x x x x de tarentaise en Région publiques CLUB club med paris 75 aime la plagne MEDITERRAN plagne 2100 73210 2 onl 3 159 000 f 05/11/15 075 056 15 O 1466 x x x x x plagne 2100 EE la croix rhone 69 aime la plagne METIFIOT first stop 73210 5 t 1 f 07/01/16 069 123 15 O 0127 x x x d'aime gare de rhone 69 aiton AREA aiton sud 73220 iop 1 169 400 f 27/01/16 069 123 15 O 0166 x peage gare de rhone 69 aiton AREA aiton nord 73220 iop 1 177 800 f 27/01/16 069 123 15 O 0166 x peage 8 avenue de paris 75 aix les bains adrea mutuelle agence 73100 5 w 1 f 09/11/15 075 056 16 O 9073 verdun CITYA agence 15 avenue de indre et loire 37 aix les bains 73100 5 w 3 f 03/08/16 037 15 47b x Immobilier charbonnier verdun agence 32 place paris 75 aix les bains BNP PARIBAS 73100 5 w 2 f 04/11/15 075 056 15 O 2098 clemenceau clemenceau 20 place agence hauts de seine 92 aix les bains MANPOWER georges 73100 5 w 3 11 750 f 18/12/15 -

Press Dossier Winter 2018-2019 Summary

FROM FATHER TO SON, THE HEART OF THE SAVOY PRESS DOSSIER WINTER 2018-2019 SUMMARY 4 3 stars in the Michelin Guide: an historic first 20 The story of a family with a passion for building for the Savoy 22 The Savoy: historical and culinary heritage 6 Events • A Menu with 4 triple starred Savoyard Chefs 30 A cuisine signed “Meilleur” th • Oenological evenings: La Bouitte celebrates the 50 ! 36 Les 3 Vallées in the Vanoise, beyond one’s imagination ... 10 New in 2018 and 2019: 40 A ***** “Relais & Châteaux” hotel • Creation of the Maison Meilleur in Saint Martin de Belleville • La Bouitte*****, a unique experience combining authenticity, 42 The Bèla Vya Spa: philosophy and choice the art of living and luxury 47 Practical information and tariffs • Spa "La Bèla Vya": treatments, equipments and a growing cosmetic brand • New culinary creations “La Bouitte … or a family adventure which has become a saga! Year after year, in complete discretion, René and Maxime Meilleur – a father and son partnership – have forged a restaurant with a rare genuineness, a superb ode to the Savoy. Each ingredient has its place, cooked to perfection, with no excess. The dishes, overflowing with original aromas, exude, just simply, happiness.” “If you have come a long way to enjoy La Bouitte’s culinary excellence, why not stay the night? In an adjoining chalet, 6 “mountain/chic” bedrooms and suites are waiting for you. A real cocoon!” (The 2018 Michelin Guide – Restaurant classification: 3 stars and 3 red forks – Hotel classification: 3 red lodges) 2 RESTAURANT RENÉ