Maxwell's Equations Lecture 20 : Magnetostatics and Ohms Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electrostatics Vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics

Electrostatics vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics Stationary charges ⇒ Constant Electric Field Steady currents ⇒ Constant Magnetic Field Coulomb’s Law Biot-Savart’s Law 1 ̂ ̂ 4 4 (Inverse Square Law) (Inverse Square Law) Electric field is the negative gradient of the Magnetic field is the curl of magnetic vector electric scalar potential. potential. 1 ′ ′ ′ ′ 4 |′| 4 |′| Electric Scalar Potential Magnetic Vector Potential Three Poisson’s equations for solving Poisson’s equation for solving electric scalar magnetic vector potential potential. Discrete 2 Physical Dipole ′′′ Continuous Magnetic Dipole Moment Electric Dipole Moment 1 1 1 3 ∙̂̂ 3 ∙̂̂ 4 4 Electric field cause by an electric dipole Magnetic field cause by a magnetic dipole Torque on an electric dipole Torque on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric force on an electric dipole Magnetic force on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric Potential Energy Magnetic Potential Energy of an electric dipole of a magnetic dipole Electric Dipole Moment per unit volume Magnetic Dipole Moment per unit volume (Polarisation) (Magnetisation) ∙ Volume Bound Charge Density Volume Bound Current Density ∙ Surface Bound Charge Density Surface Bound Current Density Volume Charge Density Volume Current Density Net , Free , Bound Net , Free , Bound Volume Charge Volume Current Net , Free , Bound Net ,Free , Bound 1 = Electric field = Magnetic field = Electric Displacement = Auxiliary -

Review of Electrostatics and Magenetostatics

Review of electrostatics and magenetostatics January 12, 2016 1 Electrostatics 1.1 Coulomb’s law and the electric field Starting from Coulomb’s law for the force produced by a charge Q at the origin on a charge q at x, qQ F (x) = 2 x^ 4π0 jxj where x^ is a unit vector pointing from Q toward q. We may generalize this to let the source charge Q be at an arbitrary postion x0 by writing the distance between the charges as jx − x0j and the unit vector from Qto q as x − x0 jx − x0j Then Coulomb’s law becomes qQ x − x0 x − x0 F (x) = 2 0 4π0 jx − xij jx − x j Define the electric field as the force per unit charge at any given position, F (x) E (x) ≡ q Q x − x0 = 3 4π0 jx − x0j We think of the electric field as existing at each point in space, so that any charge q placed at x experiences a force qE (x). Since Coulomb’s law is linear in the charges, the electric field for multiple charges is just the sum of the fields from each, n X qi x − xi E (x) = 4π 3 i=1 0 jx − xij Knowing the electric field is equivalent to knowing Coulomb’s law. To formulate the equivalent of Coulomb’s law for a continuous distribution of charge, we introduce the charge density, ρ (x). We can define this as the total charge per unit volume for a volume centered at the position x, in the limit as the volume becomes “small”. -

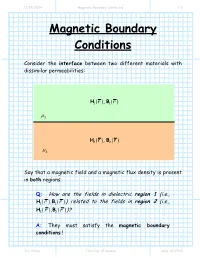

Magnetic Boundary Conditions 1/6

11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 1/6 Magnetic Boundary Conditions Consider the interface between two different materials with dissimilar permeabilities: HB11(r,) (r) µ1 HB22(r,) (r) µ2 Say that a magnetic field and a magnetic flux density is present in both regions. Q: How are the fields in dielectric region 1 (i.e., HB11()rr, ()) related to the fields in region 2 (i.e., HB22()rr, ())? A: They must satisfy the magnetic boundary conditions ! Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 2/6 First, let’s write the fields at the interface in terms of their normal (e.g.,Hn ()r ) and tangential (e.g.,Ht (r ) ) vector components: H r = H r + H r H1n ()r 1 ( ) 1t ( ) 1n () ˆan µ 1 H1t (r ) H2t (r ) H2n ()r H2 (r ) = H2t (r ) + H2n ()r µ 2 Our first boundary condition states that the tangential component of the magnetic field is continuous across a boundary. In other words: HH12tb(rr) = tb( ) where rb denotes to any point along the interface (e.g., material boundary). Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 3/6 The tangential component of the magnetic field on one side of the material boundary is equal to the tangential component on the other side ! We can likewise consider the magnetic flux densities on the material interface in terms of their normal and tangential components: BHrr= µ B1n ()r 111( ) ( ) ˆan µ 1 B1t (r ) B2t (r ) B2n ()r BH222(rr) = µ ( ) µ2 The second magnetic boundary condition states that the normal vector component of the magnetic flux density is continuous across the material boundary. -

How to Introduce the Magnetic Dipole Moment

IOP PUBLISHING EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICS Eur. J. Phys. 33 (2012) 1313–1320 doi:10.1088/0143-0807/33/5/1313 How to introduce the magnetic dipole moment M Bezerra, W J M Kort-Kamp, M V Cougo-Pinto and C Farina Instituto de F´ısica, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Caixa Postal 68528, CEP 21941-972, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] Received 17 May 2012, in final form 26 June 2012 Published 19 July 2012 Online at stacks.iop.org/EJP/33/1313 Abstract We show how the concept of the magnetic dipole moment can be introduced in the same way as the concept of the electric dipole moment in introductory courses on electromagnetism. Considering a localized steady current distribution, we make a Taylor expansion directly in the Biot–Savart law to obtain, explicitly, the dominant contribution of the magnetic field at distant points, identifying the magnetic dipole moment of the distribution. We also present a simple but general demonstration of the torque exerted by a uniform magnetic field on a current loop of general form, not necessarily planar. For pedagogical reasons we start by reviewing briefly the concept of the electric dipole moment. 1. Introduction The general concepts of electric and magnetic dipole moments are commonly found in our daily life. For instance, it is not rare to refer to polar molecules as those possessing a permanent electric dipole moment. Concerning magnetic dipole moments, it is difficult to find someone who has never heard about magnetic resonance imaging (or has never had such an examination). -

Gauss' Theorem (See History for Rea- Son)

Gauss’ Law Contents 1 Gauss’s law 1 1.1 Qualitative description ......................................... 1 1.2 Equation involving E field ....................................... 1 1.2.1 Integral form ......................................... 1 1.2.2 Differential form ....................................... 2 1.2.3 Equivalence of integral and differential forms ........................ 2 1.3 Equation involving D field ....................................... 2 1.3.1 Free, bound, and total charge ................................. 2 1.3.2 Integral form ......................................... 2 1.3.3 Differential form ....................................... 2 1.4 Equivalence of total and free charge statements ............................ 2 1.5 Equation for linear materials ...................................... 2 1.6 Relation to Coulomb’s law ....................................... 3 1.6.1 Deriving Gauss’s law from Coulomb’s law .......................... 3 1.6.2 Deriving Coulomb’s law from Gauss’s law .......................... 3 1.7 See also ................................................ 3 1.8 Notes ................................................. 3 1.9 References ............................................... 3 1.10 External links ............................................. 3 2 Electric flux 4 2.1 See also ................................................ 4 2.2 References ............................................... 4 2.3 External links ............................................. 4 3 Ampère’s circuital law 5 3.1 Ampère’s original -

Temporal Analysis of Radiating Current Densities

Temporal analysis of radiating current densities Wei Guoa aP. O. Box 470011, Charlotte, North Carolina 28247, USA ARTICLE HISTORY Compiled August 10, 2021 ABSTRACT From electromagnetic wave equations, it is first found that, mathematically, any current density that emits an electromagnetic wave into the far-field region has to be differentiable in time infinitely, and that while the odd-order time derivatives of the current density are built in the emitted electric field, the even-order deriva- tives are built in the emitted magnetic field. With the help of Faraday’s law and Amp`ere’s law, light propagation is then explained as a process involving alternate creation of electric and magnetic fields. From this explanation, the preceding math- ematical result is demonstrated to be physically sound. It is also explained why the conventional retarded solutions to the wave equations fail to describe the emitted fields. KEYWORDS Light emission; electromagnetic wave equations; current density In electrodynamics [1–3], a time-dependent current density ~j(~r, t) and a time- dependent charge density ρ(~r, t), all evaluated at position ~r and time t, are known to be the sources of an emitted electric field E~ and an emitted magnetic field B~ : 1 ∂2 4π ∂ ∇2E~ − E~ = ~j + 4π∇ρ, (1) c2 ∂t2 c2 ∂t and 1 ∂2 4π ∇2B~ − B~ = − ∇× ~j, (2) c2 ∂t2 c2 where c is the speed of these emitted fields in vacuum. See Refs. [3,4] for derivation of these equations. (In some theories [5], on the other hand, ρ and ~j are argued to arXiv:2108.04069v1 [physics.class-ph] 6 Aug 2021 be responsible for instantaneous action-at-a-distance fields, not for fields propagating with speed c.) Note that when the fields are observed in the far-field region, the contribution to E~ from ρ can be practically ignored [6], meaning that, in that region, Eq. -

Electric Current and Power

Chapter 10: Electric Current and Power Chapter Learning Objectives: After completing this chapter the student will be able to: Calculate a line integral Calculate the total current flowing through a surface given the current density. Calculate the resistance, current, electric field, and current density in a material knowing the material composition, geometry, and applied voltage. Calculate the power density and total power when given the current density and electric field. You can watch the video associated with this chapter at the following link: Historical Perspective: André-Marie Ampère (1775-1836) was a French physicist and mathematician who did ground-breaking work in electromagnetism. He was equally skilled as an experimentalist and as a theorist. He invented both the solenoid and the telegraph. The SI unit for current, the Ampere (or Amp) is named after him, as well as Ampere’s Law, which is one of the four equations that form the foundation of electromagnetic field theory. Photo credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ampere_Andre_1825.jpg, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. 1 10.1 Mathematical Prelude: Line Integrals As we saw in section 5.1, a surface integral requires that we take the dot product of a vector field with a vector that is perpendicular to a specified surface at every point along the surface, and then to integrate the resulting dot product over the surface. Surface integrals must always be a double integral, since they must involve an integral over a two-dimensional surface. We also have a special symbol for a surface integral over a closed surface, such as a sphere or a cube: (Copies of Equations 5.1 and 5.2) While a surface integral requires a double integral to be taken of a dot product over a surface, a line integral requires a single integral to be taken of a dot product over a linear path. -

Magnetostatics: Part 1 We Present Magnetostatics in Comparison with Electrostatics

Magnetostatics: Part 1 We present magnetostatics in comparison with electrostatics. Sources of the fields: Electric field E: Coulomb’s law Magnetic field B: Biot-Savart law Forces exerted by the fields: Electric: F = qE Mind the notations, both Magnetic: F = qvB printed and hand‐written Does the magnetic force do any work to the charge? F B, F v Positive charge moving at v B Negative charge moving at v B Steady state: E = vB By measuring the polarity of the induced voltage, we can determine the sign of the moving charge. If the moving charge carriers is in a perfect conductor, then we can have an electric field inside the perfect conductor. Does this contradict what we have learned in electrostatics? Notice that the direction of the magnetic force is the same for both positive and negative charge carriers. Magnetic force on a current carrying wire The magnetic force is in the same direction regardless of the charge carrier sign. If the charge carrier is negative Carrier density Charge of each carrier For a small piece of the wire dl scalar Notice that v // dl A current-carrying wire in an external magnetic field feels the force exerted by the field. If the wire is not fixed, it will be moved by the magnetic force. Some work must be done. Does this contradict what we just said? For a wire from point A to point B, For a wire loop, If B is a constant all along the loop, because Let’s look at a rectangular wire loop in a uniform magnetic field B. -

Modeling of Ferrofluid Passive Cooling System

Excerpt from the Proceedings of the COMSOL Conference 2010 Boston Modeling of Ferrofluid Passive Cooling System Mengfei Yang*,1,2, Robert O’Handley2 and Zhao Fang2,3 1M.I.T., 2Ferro Solutions, Inc, 3Penn. State Univ. *500 Memorial Dr, Cambridge, MA 02139, [email protected] Abstract: The simplicity of a ferrofluid-based was to develop a model that supports results passive cooling system makes it an appealing from experiments conducted on a cylindrical option for devices with limited space or other container of ferrofluid with a heat source and physical constraints. The cooling system sink [Figure 1]. consists of a permanent magnet and a ferrofluid. The experiments involved changing the Ferrofluids are composed of nanoscale volume of the ferrofluid and moving the magnet ferromagnetic particles with a temperature- to different positions outside the ferrofluid dependant magnetization suspended in a liquid container. These experiments tested 1) the effect solvent. The cool, magnetic ferrofluid near the of bringing the heat source and heat sink closer heat sink is attracted toward a magnet positioned together and using less ferrofluid, and 2) the near the heat source, thereby displacing the hot, optimal position for the permanent magnet paramagnetic ferrofluid near the heat source and between the heat source and sink. In the model, setting up convective cooling. This paper temperature-dependent magnetic properties were explores how COMSOL Multiphysics can be incorporated into the force component of the used to model a simple cylinder representation of momentum equation, which was coupled to the such a cooling system. Numerical results from heat transfer module. The model was compared the model displayed the same trends as empirical with experimental results for steady-state data from experiments conducted on the cylinder temperature trends and for appropriate velocity cooling system. -

PHYS 352 Electromagnetic Waves

Part 1: Fundamentals These are notes for the first part of PHYS 352 Electromagnetic Waves. This course follows on from PHYS 350. At the end of that course, you will have seen the full set of Maxwell's equations, which in vacuum are ρ @B~ r~ · E~ = r~ × E~ = − 0 @t @E~ r~ · B~ = 0 r~ × B~ = µ J~ + µ (1.1) 0 0 0 @t with @ρ r~ · J~ = − : (1.2) @t In this course, we will investigate the implications and applications of these results. We will cover • electromagnetic waves • energy and momentum of electromagnetic fields • electromagnetism and relativity • electromagnetic waves in materials and plasmas • waveguides and transmission lines • electromagnetic radiation from accelerated charges • numerical methods for solving problems in electromagnetism By the end of the course, you will be able to calculate the properties of electromagnetic waves in a range of materials, calculate the radiation from arrangements of accelerating charges, and have a greater appreciation of the theory of electromagnetism and its relation to special relativity. The spirit of the course is well-summed up by the \intermission" in Griffith’s book. After working from statics to dynamics in the first seven chapters of the book, developing the full set of Maxwell's equations, Griffiths comments (I paraphrase) that the full power of electromagnetism now lies at your fingertips, and the fun is only just beginning. It is a disappointing ending to PHYS 350, but an exciting place to start PHYS 352! { 2 { Why study electromagnetism? One reason is that it is a fundamental part of physics (one of the four forces), but it is also ubiquitous in everyday life, technology, and in natural phenomena in geophysics, astrophysics or biophysics. -

Ee334lect37summaryelectroma

EE334 Electromagnetic Theory I Todd Kaiser Maxwell’s Equations: Maxwell’s equations were developed on experimental evidence and have been found to govern all classical electromagnetic phenomena. They can be written in differential or integral form. r r r Gauss'sLaw ∇ ⋅ D = ρ D ⋅ dS = ρ dv = Q ∫∫ enclosed SV r r r Nomagneticmonopoles ∇ ⋅ B = 0 ∫ B ⋅ dS = 0 S r r ∂B r r ∂ r r Faraday'sLaw ∇× E = − E ⋅ dl = − B ⋅ dS ∫∫S ∂t C ∂t r r r ∂D r r r r ∂ r r Modified Ampere'sLaw ∇× H = J + H ⋅ dl = J ⋅ dS + D ⋅ dS ∫ ∫∫SS ∂t C ∂t where: E = Electric Field Intensity (V/m) D = Electric Flux Density (C/m2) H = Magnetic Field Intensity (A/m) B = Magnetic Flux Density (T) J = Electric Current Density (A/m2) ρ = Electric Charge Density (C/m3) The Continuity Equation for current is consistent with Maxwell’s Equations and the conservation of charge. It can be used to derive Kirchhoff’s Current Law: r ∂ρ ∂ρ r ∇ ⋅ J + = 0 if = 0 ∇ ⋅ J = 0 implies KCL ∂t ∂t Constitutive Relationships: The field intensities and flux densities are related by using the constitutive equations. In general, the permittivity (ε) and the permeability (µ) are tensors (different values in different directions) and are functions of the material. In simple materials they are scalars. r r r r D = ε E ⇒ D = ε rε 0 E r r r r B = µ H ⇒ B = µ r µ0 H where: εr = Relative permittivity ε0 = Vacuum permittivity µr = Relative permeability µ0 = Vacuum permeability Boundary Conditions: At abrupt interfaces between different materials the following conditions hold: r r r r nˆ × (E1 − E2 )= 0 nˆ ⋅(D1 − D2 )= ρ S r r r r r nˆ × ()H1 − H 2 = J S nˆ ⋅ ()B1 − B2 = 0 where: n is the normal vector from region-2 to region-1 Js is the surface current density (A/m) 2 ρs is the surface charge density (C/m ) 1 Electrostatic Fields: When there are no time dependent fields, electric and magnetic fields can exist as independent fields. -

Classical Electromagnetism - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 6

Classical electromagnetism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 6 Classical electromagnetism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Classical electrodynamics) Classical electromagnetism (or classical electrodynamics ) is a Electromagnetism branch of theoretical physics that studies consequences of the electromagnetic forces between electric charges and currents. It provides an excellent description of electromagnetic phenomena whenever the relevant length scales and field strengths are large enough that quantum mechanical effects are negligible (see quantum electrodynamics). Fundamental physical aspects of classical electrodynamics are presented e.g. by Feynman, Electricity · Magnetism Leighton and Sands, [1] Panofsky and Phillips, [2] and Jackson. [3] Electrostatics Electric charge · Coulomb's law · The theory of electromagnetism was developed over the course of the 19th century, most prominently by James Clerk Maxwell. For Electric field · Electric flux · a detailed historical account, consult Pauli, [4] Whittaker, [5] and Gauss's law · Electric potential · Pais. [6] See also History of optics, History of electromagnetism Electrostatic induction · and Maxwell's equations . Electric dipole moment · Polarization density Ribari č and Šušteršič[7] considered a dozen open questions in the current understanding of classical electrodynamics; to this end Magnetostatics they studied and cited about 240 references from 1903 to 1989. Ampère's law · Electric current · The outstanding problem with classical electrodynamics, as stated Magnetic field · Magnetization · [3] by Jackson, is that we are able to obtain and study relevant Magnetic flux · Biot–Savart law · solutions of its basic equations only in two limiting cases: »... one in which the sources of charges and currents are specified and the Magnetic dipole moment · resulting electromagnetic fields are calculated, and the other in Gauss's law for magnetism which external electromagnetic fields are specified and the Electrodynamics motion of charged particles or currents is calculated..