Lorentz-Violating Electrostatics and Magnetostatics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harvard Physics Circle Lecture 14: Magnetism, Biot-Savart, Ampere’S Law

Harvard Physics Circle Lecture 14: Magnetism, Biot-Savart, Ampere’s Law Atınç Çağan Şengül January 30th, 2021 1 Theory 1.1 Magnetic Fields We are dealing with the same problem of how charged particles interact with each other. We have a group of source charges and a test charge that moves under the influence of these source charges. Unlike electrostatics, however, the source charges are in motion. One of the simplest experiments one can do to gain insight on how magnetism works is observing two parallel wires that have currents flowing through them. The force causing this attraction and repulsion is not electrostatic since the wires are neutral. Even if they were not neutral, flipping the wires would not flip the direction of the force as we see in the experiment. Magnetic fields are what is responsible for this phenomenon. A stationary charge produces only and electric field E~ around it, while a moving charge creates a magnetic field B~ . We will first study the force acting on a charge under the influence of an ambient magnetic field, before we delve into how moving charges generate such magnetic fields. 1 1.2 The Lorentz Force Law For a particle with charge q moving with velocity ~v in a magnetic field B~ , the force acting on the particle by the magnetic field is given by, F~ = q(~v × B~ ): (1) This is known as the Lorentz force law. Just like F = ma, this law is based on experiments rather than being derived. Notice that unlike the electrostatic version of this law where the force is parallel to the electric field (F~ = qE~ ), here, the force is perpendicular to both the velocity of the particle and the magnetic field. -

On the History of the Radiation Reaction1 Kirk T

On the History of the Radiation Reaction1 Kirk T. McDonald Joseph Henry Laboratories, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 (May 6, 2017; updated March 18, 2020) 1 Introduction Apparently, Kepler considered the pointing of comets’ tails away from the Sun as evidence for radiation pressure of light [2].2 Following Newton’s third law (see p. 83 of [3]), one might suppose there to be a reaction of the comet back on the incident light. However, this theme lay largely dormant until Poincar´e (1891) [37, 41] and Planck (1896) [46] discussed the effect of “radiation damping” on an oscillating electric charge that emits electromagnetic radiation. Already in 1892, Lorentz [38] had considered the self force on an extended, accelerated charge e, finding that for low velocity v this force has the approximate form (in Gaussian units, where c is the speed of light in vacuum), independent of the radius of the charge, 3e2 d2v 2e2v¨ F = = . (v c). (1) self 3c3 dt2 3c3 Lorentz made no connection at the time between this force and radiation, which connection rather was first made by Planck [46], who considered that there should be a damping force on an accelerated charge in reaction to its radiation, and by a clever transformation arrived at a “radiation-damping” force identical to eq. (1). Today, Lorentz is often credited with identifying eq. (1) as the “radiation-reaction force”, and the contribution of Planck is seldom acknowledged. This note attempts to review the history of thoughts on the “radiation reaction”, which seems to be in conflict with the brief discussions in many papers and “textbooks”.3 2 What is “Radiation”? The “radiation reaction” would seem to be a reaction to “radiation”, but the concept of “radiation” is remarkably poorly defined in the literature. -

Electrostatics Vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics

Electrostatics vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics Stationary charges ⇒ Constant Electric Field Steady currents ⇒ Constant Magnetic Field Coulomb’s Law Biot-Savart’s Law 1 ̂ ̂ 4 4 (Inverse Square Law) (Inverse Square Law) Electric field is the negative gradient of the Magnetic field is the curl of magnetic vector electric scalar potential. potential. 1 ′ ′ ′ ′ 4 |′| 4 |′| Electric Scalar Potential Magnetic Vector Potential Three Poisson’s equations for solving Poisson’s equation for solving electric scalar magnetic vector potential potential. Discrete 2 Physical Dipole ′′′ Continuous Magnetic Dipole Moment Electric Dipole Moment 1 1 1 3 ∙̂̂ 3 ∙̂̂ 4 4 Electric field cause by an electric dipole Magnetic field cause by a magnetic dipole Torque on an electric dipole Torque on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric force on an electric dipole Magnetic force on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric Potential Energy Magnetic Potential Energy of an electric dipole of a magnetic dipole Electric Dipole Moment per unit volume Magnetic Dipole Moment per unit volume (Polarisation) (Magnetisation) ∙ Volume Bound Charge Density Volume Bound Current Density ∙ Surface Bound Charge Density Surface Bound Current Density Volume Charge Density Volume Current Density Net , Free , Bound Net , Free , Bound Volume Charge Volume Current Net , Free , Bound Net ,Free , Bound 1 = Electric field = Magnetic field = Electric Displacement = Auxiliary -

Review of Electrostatics and Magenetostatics

Review of electrostatics and magenetostatics January 12, 2016 1 Electrostatics 1.1 Coulomb’s law and the electric field Starting from Coulomb’s law for the force produced by a charge Q at the origin on a charge q at x, qQ F (x) = 2 x^ 4π0 jxj where x^ is a unit vector pointing from Q toward q. We may generalize this to let the source charge Q be at an arbitrary postion x0 by writing the distance between the charges as jx − x0j and the unit vector from Qto q as x − x0 jx − x0j Then Coulomb’s law becomes qQ x − x0 x − x0 F (x) = 2 0 4π0 jx − xij jx − x j Define the electric field as the force per unit charge at any given position, F (x) E (x) ≡ q Q x − x0 = 3 4π0 jx − x0j We think of the electric field as existing at each point in space, so that any charge q placed at x experiences a force qE (x). Since Coulomb’s law is linear in the charges, the electric field for multiple charges is just the sum of the fields from each, n X qi x − xi E (x) = 4π 3 i=1 0 jx − xij Knowing the electric field is equivalent to knowing Coulomb’s law. To formulate the equivalent of Coulomb’s law for a continuous distribution of charge, we introduce the charge density, ρ (x). We can define this as the total charge per unit volume for a volume centered at the position x, in the limit as the volume becomes “small”. -

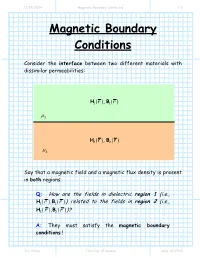

Magnetic Boundary Conditions 1/6

11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 1/6 Magnetic Boundary Conditions Consider the interface between two different materials with dissimilar permeabilities: HB11(r,) (r) µ1 HB22(r,) (r) µ2 Say that a magnetic field and a magnetic flux density is present in both regions. Q: How are the fields in dielectric region 1 (i.e., HB11()rr, ()) related to the fields in region 2 (i.e., HB22()rr, ())? A: They must satisfy the magnetic boundary conditions ! Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 2/6 First, let’s write the fields at the interface in terms of their normal (e.g.,Hn ()r ) and tangential (e.g.,Ht (r ) ) vector components: H r = H r + H r H1n ()r 1 ( ) 1t ( ) 1n () ˆan µ 1 H1t (r ) H2t (r ) H2n ()r H2 (r ) = H2t (r ) + H2n ()r µ 2 Our first boundary condition states that the tangential component of the magnetic field is continuous across a boundary. In other words: HH12tb(rr) = tb( ) where rb denotes to any point along the interface (e.g., material boundary). Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 3/6 The tangential component of the magnetic field on one side of the material boundary is equal to the tangential component on the other side ! We can likewise consider the magnetic flux densities on the material interface in terms of their normal and tangential components: BHrr= µ B1n ()r 111( ) ( ) ˆan µ 1 B1t (r ) B2t (r ) B2n ()r BH222(rr) = µ ( ) µ2 The second magnetic boundary condition states that the normal vector component of the magnetic flux density is continuous across the material boundary. -

The Lorentz Force

CLASSICAL CONCEPT REVIEW 14 The Lorentz Force We can find empirically that a particle with mass m and electric charge q in an elec- tric field E experiences a force FE given by FE = q E LF-1 It is apparent from Equation LF-1 that, if q is a positive charge (e.g., a proton), FE is parallel to, that is, in the direction of E and if q is a negative charge (e.g., an electron), FE is antiparallel to, that is, opposite to the direction of E (see Figure LF-1). A posi- tive charge moving parallel to E or a negative charge moving antiparallel to E is, in the absence of other forces of significance, accelerated according to Newton’s second law: q F q E m a a E LF-2 E = = 1 = m Equation LF-2 is, of course, not relativistically correct. The relativistically correct force is given by d g mu u2 -3 2 du u2 -3 2 FE = q E = = m 1 - = m 1 - a LF-3 dt c2 > dt c2 > 1 2 a b a b 3 Classically, for example, suppose a proton initially moving at v0 = 10 m s enters a region of uniform electric field of magnitude E = 500 V m antiparallel to the direction of E (see Figure LF-2a). How far does it travel before coming (instanta> - neously) to rest? From Equation LF-2 the acceleration slowing the proton> is q 1.60 * 10-19 C 500 V m a = - E = - = -4.79 * 1010 m s2 m 1.67 * 10-27 kg 1 2 1 > 2 E > The distance Dx traveled by the proton until it comes to rest with vf 0 is given by FE • –q +q • FE 2 2 3 2 vf - v0 0 - 10 m s Dx = = 2a 2 4.79 1010 m s2 - 1* > 2 1 > 2 Dx 1.04 10-5 m 1.04 10-3 cm Ϸ 0.01 mm = * = * LF-1 A positively charged particle in an electric field experiences a If the same proton is injected into the field perpendicular to E (or at some angle force in the direction of the field. -

The Lorentz Law of Force and Its Connections to Hidden Momentum

The Lorentz force law and its connections to hidden momentum, the Einstein-Laub force, and the Aharonov-Casher effect Masud Mansuripur College of Optical Sciences, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 [Published in IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, Vol. 50, No. 4, 1300110, pp1-10 (2014)] Abstract. The Lorentz force of classical electrodynamics, when applied to magnetic materials, gives rise to hidden energy and hidden momentum. Removing the contributions of hidden entities from the Poynting vector, from the electromagnetic momentum density, and from the Lorentz force and torque densities simplifies the equations of the classical theory. In particular, the reduced expression of the electromagnetic force-density becomes very similar (but not identical) to the Einstein-Laub expression for the force exerted by electric and magnetic fields on a distribution of charge, current, polarization and magnetization. Examples reveal the similarities and differences among various equations that describe the force and torque exerted by electromagnetic fields on material media. An important example of the simplifications afforded by the Einstein-Laub formula is provided by a magnetic dipole moving in a static electric field and exhibiting the Aharonov-Casher effect. 1. Introduction. The classical theory of electrodynamics is based on Maxwell’s equations and the Lorentz force law [1-4]. In their microscopic version, Maxwell’s equations relate the electromagnetic (EM) fields, ( , ) and ( , ), to the spatio-temporal distribution of electric charge and current densities, ( , ) and ( , ). In any closed system consisting of an arbitrary distribution of charge and 푬current,풓 푡 Maxwell’s푩 풓 푡 equations uniquely determine the field distributions provided that the휌 sources,풓 푡 푱 and풓 푡 , are fully specified in advance. -

Magnetostatics: Part 1 We Present Magnetostatics in Comparison with Electrostatics

Magnetostatics: Part 1 We present magnetostatics in comparison with electrostatics. Sources of the fields: Electric field E: Coulomb’s law Magnetic field B: Biot-Savart law Forces exerted by the fields: Electric: F = qE Mind the notations, both Magnetic: F = qvB printed and hand‐written Does the magnetic force do any work to the charge? F B, F v Positive charge moving at v B Negative charge moving at v B Steady state: E = vB By measuring the polarity of the induced voltage, we can determine the sign of the moving charge. If the moving charge carriers is in a perfect conductor, then we can have an electric field inside the perfect conductor. Does this contradict what we have learned in electrostatics? Notice that the direction of the magnetic force is the same for both positive and negative charge carriers. Magnetic force on a current carrying wire The magnetic force is in the same direction regardless of the charge carrier sign. If the charge carrier is negative Carrier density Charge of each carrier For a small piece of the wire dl scalar Notice that v // dl A current-carrying wire in an external magnetic field feels the force exerted by the field. If the wire is not fixed, it will be moved by the magnetic force. Some work must be done. Does this contradict what we just said? For a wire from point A to point B, For a wire loop, If B is a constant all along the loop, because Let’s look at a rectangular wire loop in a uniform magnetic field B. -

Modeling of Ferrofluid Passive Cooling System

Excerpt from the Proceedings of the COMSOL Conference 2010 Boston Modeling of Ferrofluid Passive Cooling System Mengfei Yang*,1,2, Robert O’Handley2 and Zhao Fang2,3 1M.I.T., 2Ferro Solutions, Inc, 3Penn. State Univ. *500 Memorial Dr, Cambridge, MA 02139, [email protected] Abstract: The simplicity of a ferrofluid-based was to develop a model that supports results passive cooling system makes it an appealing from experiments conducted on a cylindrical option for devices with limited space or other container of ferrofluid with a heat source and physical constraints. The cooling system sink [Figure 1]. consists of a permanent magnet and a ferrofluid. The experiments involved changing the Ferrofluids are composed of nanoscale volume of the ferrofluid and moving the magnet ferromagnetic particles with a temperature- to different positions outside the ferrofluid dependant magnetization suspended in a liquid container. These experiments tested 1) the effect solvent. The cool, magnetic ferrofluid near the of bringing the heat source and heat sink closer heat sink is attracted toward a magnet positioned together and using less ferrofluid, and 2) the near the heat source, thereby displacing the hot, optimal position for the permanent magnet paramagnetic ferrofluid near the heat source and between the heat source and sink. In the model, setting up convective cooling. This paper temperature-dependent magnetic properties were explores how COMSOL Multiphysics can be incorporated into the force component of the used to model a simple cylinder representation of momentum equation, which was coupled to the such a cooling system. Numerical results from heat transfer module. The model was compared the model displayed the same trends as empirical with experimental results for steady-state data from experiments conducted on the cylinder temperature trends and for appropriate velocity cooling system. -

The Lorentz Force and the Radiation Pressure of Light

The Lorentz Force and the Radiation Pressure of Light Tony Rothman∗ and Stephen Boughn† Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544 Haverford College, Haverford PA 19041 LATEX-ed October 23, 2018 Abstract In order to make plausible the idea that light exerts a pressure on matter, some introductory physics texts consider the force exerted by an electromag- netic wave on an electron. The argument as presented is both mathematically incorrect and has several serious conceptual difficulties without obvious resolu- tion at the classical, yet alone introductory, level. We discuss these difficulties and propose an alternative demonstration. PACS: 1.40.Gm, 1.55.+b, 03.50De Keywords: Electromagnetic waves, radiation pressure, Lorentz force, light 1 The Freshman Argument arXiv:0807.1310v5 [physics.class-ph] 21 Nov 2008 The interaction of light and matter plays a central role, not only in physics itself, but in any freshman electricity and magnetism course. To develop this topic most courses introduce the Lorentz force law, which gives the electromagnetic force act- ing on a charged particle, and later devote some discussion to Maxwell’s equations. Students are then persuaded that Maxwell’s equations admit wave solutions which ∗[email protected] †[email protected] 1 Lorentz... 2 travel at the speed of light, thus establishing the connection between light and elec- tromagnetic waves. At this point we unequivocally state that electromagnetic waves carry momentum in the direction of propagation via the Poynting flux and that light therefore exerts a radiation pressure on matter. This is not controversial: Maxwell himself in his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism[1] recognized that light should manifest a radiation pressure, but his demonstration is not immediately transparent to modern readers. -

Lecture 18 Relativity & Electromagnetism

Electromagnetism - Lecture 18 Relativity & Electromagnetism • Special Relativity • Current & Potential Four Vectors • Lorentz Transformations of E and B • Electromagnetic Field Tensor • Lorentz Invariance of Maxwell's Equations 1 Special Relativity in One Slide Space-time is a four-vector: xµ = [ct; x] Four-vectors have Lorentz transformations between two frames with uniform relative velocity v: 0 0 x = γ(x − βct) ct = γ(ct − βx) where β = v=c and γ = 1= 1 − β2 The factor γ leads to timepdilation and length contraction Products of four-vectors are Lorentz invariants: µ 2 2 2 2 02 0 2 2 x xµ = c t − jxj = c t − jx j = s The maximum possible speed is c where β ! 1, γ ! 1. Electromagnetism predicts waves that travel at c in a vacuum! The laws of Electromagnetism should be Lorentz invariant 2 Charge and Current Under a Lorentz transformation a static charge q at rest becomes a charge moving with velocity v. This is a current! A static charge density ρ becomes a current density J N.B. Charge is conserved by a Lorentz transformation The charge/current four-vector is: dxµ J µ = ρ = [cρ, J] dt The full Lorentz transformation is: 0 0 v J = γ(J − vρ) ρ = γ(ρ − J ) x x c2 x Note that the γ factor can be understood as a length contraction or time dilation affecting the charge and current densities 3 Notes: Diagrams: 4 Electrostatic & Vector Potentials A reminder that: 1 ρ µ0 J V = dτ A = dτ 4π0 ZV r 4π ZV r A static charge density ρ is a source of an electrostatic potential V A current density J is a source of a magnetic vector potential A Under a -

The Energy-Momentum Tensor of Electromagnetic Fields in Matter

The energy-momentum tensor of electromagnetic fields in matter Rodrigo Medina1, ∗ and J Stephany2, † 1Centro de F´ısica, Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Cient´ıficas, Apartado 20632 Caracas 1020-A, Venezuela. 2Departamento de F´ısica, Secci´on de Fen´omenos Opticos,´ Universidad Sim´on Bol´ıvar,Apartado Postal 89000, Caracas 1080-A, Venezuela. In this paper we present a complete resolution of the Abraham-Minkowski controversy about the energy-momentum tensor of the electromagnetic field in matter. This is done by introducing in our approach several new aspects which invalidate previous discussions. These are: 1)We show that for polarized matter the center of mass theorem is no longer valid in its usual form. A contribution related to microscopic spin should be considered. This allows to disregard the influencing argument done by Balacz in favor of Abraham’s momentum which discuss the motion of the center of mass of light interacting with a dielectric block. 2)The electromagnetic dipolar energy density −P · E contributes to the inertia of matter and should be incorporated covariantly to the the energy- momentum tensor of matter. This implies that there is also an electromagnetic component in matter’s momentum density given by P × B which accounts for the diference between Abraham and Minkowski’s momentum densities. The variation of this contribution explains the results of G. B. Walker, D. G. Lahoz and G. Walker’s experiment which until now was the only undisputed support to Abraham’s force. 3)A careful averaging of microscopic Lorentz’s force results in the µ 1 µ αβ unambiguos expression fd = 2 Dαβ ∂ F for the force density which the field exerts on matter.