Temporal Analysis of Radiating Current Densities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Introduce the Magnetic Dipole Moment

IOP PUBLISHING EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICS Eur. J. Phys. 33 (2012) 1313–1320 doi:10.1088/0143-0807/33/5/1313 How to introduce the magnetic dipole moment M Bezerra, W J M Kort-Kamp, M V Cougo-Pinto and C Farina Instituto de F´ısica, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Caixa Postal 68528, CEP 21941-972, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] Received 17 May 2012, in final form 26 June 2012 Published 19 July 2012 Online at stacks.iop.org/EJP/33/1313 Abstract We show how the concept of the magnetic dipole moment can be introduced in the same way as the concept of the electric dipole moment in introductory courses on electromagnetism. Considering a localized steady current distribution, we make a Taylor expansion directly in the Biot–Savart law to obtain, explicitly, the dominant contribution of the magnetic field at distant points, identifying the magnetic dipole moment of the distribution. We also present a simple but general demonstration of the torque exerted by a uniform magnetic field on a current loop of general form, not necessarily planar. For pedagogical reasons we start by reviewing briefly the concept of the electric dipole moment. 1. Introduction The general concepts of electric and magnetic dipole moments are commonly found in our daily life. For instance, it is not rare to refer to polar molecules as those possessing a permanent electric dipole moment. Concerning magnetic dipole moments, it is difficult to find someone who has never heard about magnetic resonance imaging (or has never had such an examination). -

Gauss' Theorem (See History for Rea- Son)

Gauss’ Law Contents 1 Gauss’s law 1 1.1 Qualitative description ......................................... 1 1.2 Equation involving E field ....................................... 1 1.2.1 Integral form ......................................... 1 1.2.2 Differential form ....................................... 2 1.2.3 Equivalence of integral and differential forms ........................ 2 1.3 Equation involving D field ....................................... 2 1.3.1 Free, bound, and total charge ................................. 2 1.3.2 Integral form ......................................... 2 1.3.3 Differential form ....................................... 2 1.4 Equivalence of total and free charge statements ............................ 2 1.5 Equation for linear materials ...................................... 2 1.6 Relation to Coulomb’s law ....................................... 3 1.6.1 Deriving Gauss’s law from Coulomb’s law .......................... 3 1.6.2 Deriving Coulomb’s law from Gauss’s law .......................... 3 1.7 See also ................................................ 3 1.8 Notes ................................................. 3 1.9 References ............................................... 3 1.10 External links ............................................. 3 2 Electric flux 4 2.1 See also ................................................ 4 2.2 References ............................................... 4 2.3 External links ............................................. 4 3 Ampère’s circuital law 5 3.1 Ampère’s original -

Electric Current and Power

Chapter 10: Electric Current and Power Chapter Learning Objectives: After completing this chapter the student will be able to: Calculate a line integral Calculate the total current flowing through a surface given the current density. Calculate the resistance, current, electric field, and current density in a material knowing the material composition, geometry, and applied voltage. Calculate the power density and total power when given the current density and electric field. You can watch the video associated with this chapter at the following link: Historical Perspective: André-Marie Ampère (1775-1836) was a French physicist and mathematician who did ground-breaking work in electromagnetism. He was equally skilled as an experimentalist and as a theorist. He invented both the solenoid and the telegraph. The SI unit for current, the Ampere (or Amp) is named after him, as well as Ampere’s Law, which is one of the four equations that form the foundation of electromagnetic field theory. Photo credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ampere_Andre_1825.jpg, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. 1 10.1 Mathematical Prelude: Line Integrals As we saw in section 5.1, a surface integral requires that we take the dot product of a vector field with a vector that is perpendicular to a specified surface at every point along the surface, and then to integrate the resulting dot product over the surface. Surface integrals must always be a double integral, since they must involve an integral over a two-dimensional surface. We also have a special symbol for a surface integral over a closed surface, such as a sphere or a cube: (Copies of Equations 5.1 and 5.2) While a surface integral requires a double integral to be taken of a dot product over a surface, a line integral requires a single integral to be taken of a dot product over a linear path. -

PHYS 352 Electromagnetic Waves

Part 1: Fundamentals These are notes for the first part of PHYS 352 Electromagnetic Waves. This course follows on from PHYS 350. At the end of that course, you will have seen the full set of Maxwell's equations, which in vacuum are ρ @B~ r~ · E~ = r~ × E~ = − 0 @t @E~ r~ · B~ = 0 r~ × B~ = µ J~ + µ (1.1) 0 0 0 @t with @ρ r~ · J~ = − : (1.2) @t In this course, we will investigate the implications and applications of these results. We will cover • electromagnetic waves • energy and momentum of electromagnetic fields • electromagnetism and relativity • electromagnetic waves in materials and plasmas • waveguides and transmission lines • electromagnetic radiation from accelerated charges • numerical methods for solving problems in electromagnetism By the end of the course, you will be able to calculate the properties of electromagnetic waves in a range of materials, calculate the radiation from arrangements of accelerating charges, and have a greater appreciation of the theory of electromagnetism and its relation to special relativity. The spirit of the course is well-summed up by the \intermission" in Griffith’s book. After working from statics to dynamics in the first seven chapters of the book, developing the full set of Maxwell's equations, Griffiths comments (I paraphrase) that the full power of electromagnetism now lies at your fingertips, and the fun is only just beginning. It is a disappointing ending to PHYS 350, but an exciting place to start PHYS 352! { 2 { Why study electromagnetism? One reason is that it is a fundamental part of physics (one of the four forces), but it is also ubiquitous in everyday life, technology, and in natural phenomena in geophysics, astrophysics or biophysics. -

Ee334lect37summaryelectroma

EE334 Electromagnetic Theory I Todd Kaiser Maxwell’s Equations: Maxwell’s equations were developed on experimental evidence and have been found to govern all classical electromagnetic phenomena. They can be written in differential or integral form. r r r Gauss'sLaw ∇ ⋅ D = ρ D ⋅ dS = ρ dv = Q ∫∫ enclosed SV r r r Nomagneticmonopoles ∇ ⋅ B = 0 ∫ B ⋅ dS = 0 S r r ∂B r r ∂ r r Faraday'sLaw ∇× E = − E ⋅ dl = − B ⋅ dS ∫∫S ∂t C ∂t r r r ∂D r r r r ∂ r r Modified Ampere'sLaw ∇× H = J + H ⋅ dl = J ⋅ dS + D ⋅ dS ∫ ∫∫SS ∂t C ∂t where: E = Electric Field Intensity (V/m) D = Electric Flux Density (C/m2) H = Magnetic Field Intensity (A/m) B = Magnetic Flux Density (T) J = Electric Current Density (A/m2) ρ = Electric Charge Density (C/m3) The Continuity Equation for current is consistent with Maxwell’s Equations and the conservation of charge. It can be used to derive Kirchhoff’s Current Law: r ∂ρ ∂ρ r ∇ ⋅ J + = 0 if = 0 ∇ ⋅ J = 0 implies KCL ∂t ∂t Constitutive Relationships: The field intensities and flux densities are related by using the constitutive equations. In general, the permittivity (ε) and the permeability (µ) are tensors (different values in different directions) and are functions of the material. In simple materials they are scalars. r r r r D = ε E ⇒ D = ε rε 0 E r r r r B = µ H ⇒ B = µ r µ0 H where: εr = Relative permittivity ε0 = Vacuum permittivity µr = Relative permeability µ0 = Vacuum permeability Boundary Conditions: At abrupt interfaces between different materials the following conditions hold: r r r r nˆ × (E1 − E2 )= 0 nˆ ⋅(D1 − D2 )= ρ S r r r r r nˆ × ()H1 − H 2 = J S nˆ ⋅ ()B1 − B2 = 0 where: n is the normal vector from region-2 to region-1 Js is the surface current density (A/m) 2 ρs is the surface charge density (C/m ) 1 Electrostatic Fields: When there are no time dependent fields, electric and magnetic fields can exist as independent fields. -

Bound to the Nucleus of an Atom No Longer Behave Like Point-Like Particles, but As Quantum-Mechanical Matter Waves

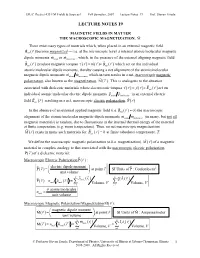

UIUC Physics 435 EM Fields & Sources I Fall Semester, 2007 Lecture Notes 19 Prof. Steven Errede LECTURE NOTES 19 MAGNETIC FIELDS IN MATTER THE MACROSCOPIC MAGNETIZATION, Μ There exist many types of materials which, when placed in an external magnetic field Bext ()r become magnetized — i.e. at the microscopic level ∃ internal atomic/molecular magnetic dipole moments matom or mmolecular , which, in the presence of the external aligning magnetic field Bext ()r produce magnetic torques τ (rmrBr) =×( ) ext ( ) which act on the individual atomic/molecular dipole moments, thereby causing a net alignment of the atomic/molecular magnetic dipole moments mmatom molecular which in turn results in a net, macroscopic magnetic polarization, also known as the magnetization, Μ (r ) . This is analogous to the situation associated with dielectric materials where electrostatic torques τ (rprEr) =×( )()ext act on individual atomic/molecular electric dipole moments ppatom molecular in an external electric field Erext () resulting in a net, macroscopic electric polarization, Ρ(r ) . In the absence of an external applied magnetic field (i.e. Brext ( ) = 0) the macroscopic alignment of the atomic/molecular magnetic dipole moments mmatom molecular (in many, but not all magnetic materials) is random, due to fluctuations in the internal thermal energy of the material at finite temperature (e.g. room temperature). Thus, no net macroscopic magnetization M ()r exists in many such materials for Brext ( ) = 0 at finite (absolute) temperature, -

Technical Notes on Classical Electromagnetism

Christine Cordula´ Dantas Technical Notes on Classical Electromagnetism With Exercises September 17, 2012 arXiv:1209.3257v1 [physics.class-ph] 14 Sep 2012 Divis˜ao de Materiais (AMR), Instituto de Aeron´autica e Espac¸o (IAE), Departamento de Ciˆencia e Tecnologia Aeroespacial (DCTA), Brazil. email: [email protected] Uses Springer LaTeX macros. Contents 1 Introduction ................................................... 1 1.1 System of units, the electric current and the electric charge........ 1 1.2 The Coulomb’s force law, the Lorentz force law, fields . ........ 2 1.3 Theunitsfortheelectromagneticfields .............. .......... 3 Problems ........................................... ........... 4 2 Maxwell’s equations ............................................ 7 2.1 Maxwell’sequations:macroscopicfield .............. .......... 7 2.1.1 Maxwell’sequationsin integralform.............. ...... 7 2.1.2 Maxwell’s equationsin differentialform .. ..... ... ....... 10 2.1.3 Continuityconditions.......................... ....... 11 2.2 Maxwell’sequations:microscopicfield .............. .......... 13 2.2.1 A note on constitutive relations in material media . ...... 13 2.2.2 Microscopicfields .............................. ..... 15 Problems ........................................... ........... 16 3 Potentials and Gauge Transformations ........................... 19 3.1 The electromagnetic scalar and vector potentials.. ............ 19 3.2 Gauge transformations: the Lorentz and the Coulomb gauges...... 21 Problems .......................................... -

UNIT – II Conductors and Dielectrics

UNIT – II Conductors and Dielectrics 2.1) Poisson’s and Laplace’s Equations: From the Gauss law we know that = Q (1) Ȅ ̾. ͧ͘ A body containing a charge density ρ uniformly distributed over the body. Then charge of that body is given by Q = (2) Ȅ ˹ ͪ͘ = (3) Ȅ ̾. ͧ͘ Ȅ ˹ ͪ͘ This is integral form of Gauss law. As per the divergence theorem = (4) Ȅ ̾. ͧ͘ Ȅ ˨. ̊ ͪ͘ (5) ˨. ̊ = ˹ This is known as point form or vector form or polar form. This is also known as Maxwell’s first equation. D = ƐE (6) Ɛ ˨. E = ρ ˨. E = û/Ɛ (7) We know that E is negative potential medium E = -˨̜ (8) From equations 7 and 8 ) = ˨. (– ˨̜ û/Ɛ 2 ˨ V = - û/Ɛ (9) Which is known as Poisson’s equation in static electric field. Consider a charge free region (insulator) the value of ρ = 0, since there is no free charges in dielectrics or insulators. 2 ˨ V = 0 This is known as Laplace’s equation. Cartesian coordinate system 2V = iͦV ˨ i3 Cylindrical coordinate system Spherical coordinate system 2.2) Electric Dipole: It is defined as two equal and opposite charges separated by a small distance. 2.3) Electric Dipole moment: It is defined as product of charge Q and distance between the two charges. It is a vector since length is in vector, length vector is directed from negative to positive charge, therefore dipole moment is from negative to positive charge. m = Ql l = l u r ur is unit vector directed from negative to positive charge. -

Worked Examples University of Oxford Second Year, Part A2

Electromagnetism: Worked Examples University of Oxford Second Year, Part A2 Caroline Terquem Department of Physics [email protected] Michaelmas Term 2018 2 Contents 1 Potentials5 1.1 Potential of an infinite line charge.......................5 1.2 Vector potential of an infinite wire.......................6 1.3 Potential of a sphere with a charge density σ = k cos θ ............7 1.4 Multipole expansion............................... 10 1.5 Electric dipole moment.............................. 11 2 Electric fields in matter 13 2.1 Field of a uniformly polarized sphere...................... 13 2.2 D and E of an insulated straight wire..................... 15 2.3 D and E of a cylinder with polarization along the axis............ 15 2.4 Linear dielectric sphere with a charge at the center............. 16 3 Magnetic fields in matter 19 3.1 Field of a uniformly magnetized sphere..................... 19 3.2 Field of a cylinder with circular magnetization................ 21 3.3 H and B of a cylinder with magnetization along the axis........... 22 3.4 H and B of a linear insulated straight wire.................. 23 3 Most of the problems are taken from: David J. Griffiths, Introduction to Electrodynamics, 4th edition (Cambridge University Press) 4 Chapter 1 Potentials 1.1 Potential of an infinite line charge (a) A straight wire, assumed infinitely long, has a constant linear charge density λ. Calculate the electric field due to the wire. Use this result to calculate the electric potential. Given the symmetry of the system, the electric field at the point P is: λdz E = 2 cos θ: ˆwire 4π0d Using d = r= cos θ and z = r tan θ, which yields dz = rdθ= cos2 θ, we get: λ π=2 λ E = cos θdθ = : 4π0r ˆ−π=2 2π0r Using cylindrical coordinates, E = −rV yields: λ V = − ln r + C; 2π0 where C is a constant. -

A Problem-Solving Approach – Chapter 5: the Magnetic Field

chapter S the magnetic field 314 The Magnetic Field The ancient Chinese knew that the iron oxide magnetite (FesO 4 ) attracted small pieces of iron. The first application of this effect was the navigation compass, which was not developed until the thirteenth century. No major advances were made again until the early nineteenth century when precise experiments discovered the properties of the magnetic field. 5-1 FORCES ON MOVING CHARGES 5-1-1 The Lorentz Force Law It was well known that magnets exert forces on each other, but in 1820 Oersted discovered that a magnet placed near a current carrying wire will align itself perpendicular to the wire. Each charge q in the wire, moving with velocity v in the magnetic field B [teslas, (kg-s 2 -A-')], felt the empirically determined Lorentz force perpendicular to both v and B f =q(vx B) (1) as illustrated in Figure 5-1. A distribution of charge feels a differential force df on each moving incremental charge element dq: df = dq(vx B) (2) V B q f q(v x B) Figure 5-1 A charge moving through a magnetic field experiences the Lorentz force perpendicular to both its motion and the magnetic field. Forces on Moving Charges 315 Moving charges over a line, surface, or volume, respectively constitute line, surface, and volume currents, as in Figure 5-2, where (2) becomes pfv x B dV= Jx B dV (J = pfv, volume current density) dS df= a-vxB dS=KXB (K = orfv, surface current density) (3) AfvxB dl =IxB dl (I=Afv, line current) B v : -- I dl =--ev di df = Idl x B (a) B dS K dS di > d1 KdSx B (b) B d V 1K----------+-. -

Maxwell's Equations Lecture 20 : Magnetostatics and Ohms Law

Module 3 : Maxwell's Equations Lecture 20 : Magnetostatics and Ohms Law Objectives In this course you will learn the following Magnetic Field and Magnetic Flux Density. Conduction Current Density J. Module 3 : Maxwell's Equations Lecture 20 : Magnetostatics and Ohms Law Magnetic Field and Magnetic Flux Density The magnetic field can be defined as the force experienced by a unit magnetic monopole. However, there are no magnetic monoples. The field due to a current element is given by the Biot-Savart law. Consider an infinitesimally small piece of a wire carrying current in it. The length of the piece is say . The current moment is then defined by the product . Since the piece of the wire can be oriented in any direction the length is a vector quantity and therefore should be denoted by . The current is a scalar quantity making the current moment is a vector quantity. Without loss of generality let us assume that the current element is located at the origin of the co-ordinate system as shown in Fig. According to the Biot - Savart's law the magnetic field ( field due to infinitesimally small current element) at a point is given as Where is the unit vector in the direction of the line joining the current element and the observation point . Since the vectors and lie in the plane of the paper, the cross-product of the two has a direction prependicular to the plane of the paper. Since the direction of the current is assumed upwards, the direction of is upwards and the direction of the magnetic field will be going into the paper as indicated by at point . -

Magnetostatics in Electrostatics, Electric Fields Constant in Time Are Produced by Stationary Charges

Section 5: Magnetostatics In electrostatics, electric fields constant in time are produced by stationary charges. In magnetostatics magnetic fields constant in time are produced by steady currents. Electric currents The electric current in a wire is the charge per unit time passing a given point. If charge dQ passes point P in Fig.5.1 per time dt the magnitude of the current is dQ I . (5.1) dt By definition, negative charges moving to the left count the same as positive charges moving to the right. In practice, there is a convention to assume that the electric current flows in the direction of motion of positive charges. Current is measured in coulombs-per-second, or amperes (A): 1A=1C/s. A line charge traveling down a wire at speed v (Fig. 5.1) constitutes a current Iv . (5.2) This is because a segment of length vt, carrying charge vt, passes point P in a time interval t. Fig. 5.1 Line current We note that current is actually a vector. A neutral wire, of course, contains as many stationary positive charges as mobile negative ones. The former do not contribute to the current. When charge flows over a surface, we describe it by the surface current density, K, defined as follows: Consider a “ribbon” of infinitesimal width dl , running parallel to the flow (Fig. 5.2). If the current in this ribbon is dI, the surface current density is dI K . (5.3) dl In words, K is the current per unit width-perpendicular-to-flow. In particular, if the mobile surface charge density is and its velocity is v, then Kv .