A Trivial Pursuit: Scrabbling for a Board Game Copyright Rationale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludopor – Platform for Creating Word Educational Games

LudoPor Word Games Creation Platform Samuel José Raposo Vieira Mira March of 2009 Acknowledgements While I have done a lot of work on this project, it would not have been possible without the help of many great people. I would like to thank my mother and my wonderful girlfriend who have encouraged me in everything I have ever done. I also owe a great amount to my thesis supervisor, Rui Prada whose advice and criticism has been critical in this project. Next I would like to thank the Ciberdúvidas community, especially Ana Martins, for having the time and will to try and experiment my prototypes. A special thanks is owed to my good friend António Leonardo and all the users that helped in this project especially the ones in the weekly meetings. 2 Abstract This thesis presents an approach for creating Word Games. We researched word games as Trivial Pursuit, Scrabble and more to establish reasons for their success. After this research we proposed a conceptual model using key concepts present in many of those games. The model defines the Game World with concepts such as the World Representation, Player, Challenges, Links, Goals and Performance Indicators. Then we created LudoPor - a prototype of a platform using some of the referred concepts. The prototype was made using an iterative design starting from paper prototypes to high fidelity prototypes using user evaluation tests to help define the right path. In this task we had the help of many users including persons of Ciberdúvidas (a Portuguese language community). Another objective of LudoPor was to create games for Ciberdúvidas that would be shown in their website. -

A Trivial Pursuit: Scrabbling for a Board Game Copyright Rationale

HALES_TRIVIAL PURSUIT 3/7/2013 1:15 PM A TRIVIAL PURSUIT: SCRABBLING FOR A BOARD GAME COPYRIGHT RATIONALE Kevin P. Hales* INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 242 I:HISTORICAL LACK OF PROTECTION FOR BOARD GAMES ......... 245 II.ARGUMENTS FAVORING COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR BOARD GAMES ................................................................. 248 A. Board Games as Creative Works Versus Practical Ones .......................................................... 248 B. Copyright Protection for Comparable Works ......... 250 1. Plays and Similar Dramatic Works ................... 250 2. Sheet Music ......................................................... 252 3. Video games ........................................................ 254 4. Computer software. ............................................. 255 5. Sui Generis Protection for Architectural Works. .................................................................. 256 C. Substantial Similarity and the “Heart” of a Work . 257 D. Benefits of Copyright ............................................... 259 1. Incentivizing Creation of Board Games ............. 259 III.LACK OF PRESSURE FOR COPYRIGHT IN BOARD GAMES ....... 262 A. Legal Hurdles........................................................... 263 B. Board Game Industry Dynamics ............................. 264 IV.ARGUMENTS AGAINST COPYRIGHT IN BOARD GAMES .......... 265 CONCLUSION ............................................................................ 268 * J.D., 2011, University -

Hasbro and Discovery Communications Announce Joint

Hasbro and Discovery Communications Announce Joint Venture to Create Television Network Dedicated to High-Quality Children's and Family Entertainment and Educational Content April 30, 2009 - Multi-Platform Initiative Planned to Premiere in Late 2010; TV Network to Reach Approximately 60 Million Nielsen Households in the U.S. Served by Discovery Kids Channel - - Joint Media Call with Hasbro CEO and Discovery CEO at 8:15 AM Eastern Today; Hasbro Investor Call with Hasbro CEO and Hasbro CFO & COO at 8:45 AM Eastern Today; See Dial-in and Webcast Details at End of Release - PAWTUCKET, R.I. and SILVER SPRING, Md., April 30 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Hasbro, Inc. (NYSE: HAS) and Discovery Communications (Nasdaq: DISCA, DISCB, DISCK) today announced an agreement to form a 50/50 joint venture, including a television network and website, dedicated to high-quality children's and family entertainment and educational programming built around some of the most well-known and beloved brands in the world. As part of the transaction, the joint venture also will receive a minority interest in the U.S. version of Hasbro.com. Both the network and the venture's online component will feature content from Hasbro's rich portfolio of entertainment and educational properties built over the past 90 years, including original programming for animation, game shows, and live-action series and specials. New programming will be based on brands such as ROMPER ROOM, TRIVIAL PURSUIT, SCRABBLE, CRANIUM, MY LITTLE PONY, G.I. JOE, GAME OF LIFE, TONKA and TRANSFORMERS, among many others. The TV network and online presence also will include content from Discovery's extensive library of award- winning children's educational programming, such as BINDI THE JUNGLE GIRL, ENDURANCE, TUTENSTEIN, HI-5, FLIGHT 29 DOWN and PEEP AND THE BIG WIDE WORLD, as well as programming from third-party producers. -

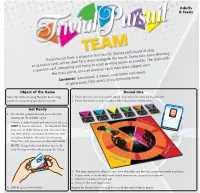

Trivial Pursuit Team Is Played in Four Rounds. During Each Round of Play, Six Question Cards Will Be Dealt Face Down Alongside the Board

Adults & Teens Trivial Pursuit Team is played in four rounds. During each round of play, six question cards will be dealt face down alongside the board. Teams take turns choosing a question card, answering and trying to score as many points as possible. The team with the most points, once all question cards have been played, wins. Gameboard, 2 movers, card holder with stand, Contents: ), 30 customizable cards. 12 game packs (360 cards Object of the Game Round One Move the farthest along the path by earning 1. Draw the first card and read it aloud. It contains the rules for Round One. points for answering questions correctly. 2. Draw the next six cards and place them face down on the table. Get Ready 1. Set out the gameboard and place the two movers on the START space. 2. Choose a deck of cards and unwrap it. Be sure NOT to shuffle the cards – it’s important that they stay in order. Remove the rules card (the top one) and the scorecard (the bottom one) and place them on the table for reference. Place the cards face down in the card holder. NOTE: To open the card holder, locate the small bumps on the side and pop the lid up. Deck 1 3. The team going first selects a card from the table and the opposing team reads it to them. 4. If your team is successful, move ahead the number of points you earned. 5. Place the card in a discard pile. 6. Now it’s the next team’s turn. -

Classification of Games for Computer Science Education

Classification of Games for Computer Science Education Peter Drake Lewis & Clark College Overview Major Categories Issues in the CS Classroom Resources Major Categories Classical Abstract Games Children’s Games Family Games Simulation Games Eurogames (”German Games”) Classical Abstract Games Simple rules Often deep strategy Backgammon, Bridge, Checkers, Chess, Go, Hex, Mancala, Nine Men’s Morris, Tic-Tac-Toe Children’s Games Simple rules Decisions are easy and rare Candyland, Cootie, Go Fish, Snakes and Ladders, War Family Games Moderately complex rules Often a high luck factor Battleship, Careers, Clue, Game of Life, Risk, Scrabble, Sorry, Monopoly, Trivial Pursuit, Yahtzee Simulation Games Extremely complex rules Theme is usually war or sports Blood Bowl, Panzer Blitz, Star Fleet Battles, Strat-o-Matic Baseball, Twilight Imperium, Wizard Kings Eurogames (”German Games”) Complexity comparable to family games Somewhat deeper strategy Carcassonne, El Grande, Puerto Rico, Ra, Samurai, Settlers of Catan, Ticket to Ride Issues in the CS Classroom Game mechanics Programming issues Cultural and thematic issues Games for particular topics Game Mechanics Time to play Number of players Number of piece types Board morphology Determinism Programming Issues Detecting or enumerating legal moves Hidden information Artificially intelligent opponent Testing Proprietary games Cultural and Thematic Issues Students may be engaged by games from their own culture Theme may attract or repel various students Religious objections A small number of students just don’t like games Games for Particular Topics Quantitative reasoning: play some games! Stacks and queues: solitaire card games Sets: word games Graphs: complicated boards OOP: dice, cards, simulations Networking: hidden information, multiplayer games AI: classical abstract games Resources http://www.boardgamegeek.com http://www.funagain.com International Computer Games Association, http://www.cs.unimaas.nl/ icga/. -

“'In a Checkers Game.'” Point Games 2. Ka-Boom!

Board Game Where It Is Found In Book Publisher 1. Checkers P.3 “’In a checkers game.’” Point Games 2. Ka-Boom! P.3 “…four letters. Ka- Blue Orange Games Boom!” 3. Anagrams P.4 “You think it’s some E.E. Fairchild Corporation kind of anagram?” 4. The Impossible Game P.6 “Impossible?” he said. United Nations Constructors 5. Dare! P.12 He’d take their dare. Parker Brothers 6-7. Hungry Hungry Hippo P.12 …like a hungry, hungry Hasbro, GeGe Co. (When and Spaghetti hippo slurping spaghetti. there’s multiple games, I wrote each publisher.) 8. Husker Dü? P.16 “Well, yippie-ki-yay Winning Moves and Husker Dü!” 9. Cranium P.17 Simon’s cranium felt Hasbro like it might explode. 10. Classified P.22 “That information is David Greene (I couldn’t classified.” find a publisher, so I wrote in the creator instead.) 11. Scramble P.24 “Scramble, scramble!” Hasbro 12. Freeze P.26 “Freeze!” shouted Ravensburger Jack’s father. 13. Mastermind P.29 “You’re like a Pressman mastermind!” 14. Dungeons and P.32 “And dungeons. And Wizards of the Coast Dragons dragons!” 15. Imagination Station P.35 His very own Playcare “imagination station.” 16. Clapper P.35 …a remote-controlled Ropoda Clapper… 17. Open Sesame P.35 He also said, “Open IDW Games Sesame,” but that was just for fun. 18. Osmosis P.41 “…through mental toytoytoy osmosis.” 19. Einstein P.43 “It’s like Einstein Artana supposedly said…” 20. Labyrinth P.45 …two sideways Ravensburger labyrinths. 21. Operation P.46 “It’s been quite an Hasbro operation.” 22. -

5-E Classroom STEM Activity: Game Night! Dr

5-E Classroom STEM Activity: Game Night! Dr. Alexandra D. Owens Toys > Melissa Hershey Engineering Fun By Ellen Egley What do toys like Transformers, Nerf, My Little Pony, Play-Doh, and Baby Alive have in common with games like Magic the Gathering, Monopoly, Jenga, Scrabble, Trivial Pursuit, Operation, Clue, and Life? 1. Chances are good you played with them at some point during your childhood (and maybe still do!). 2. They are all brought to STEM JOBS: What sparked SJ: What type of education SJ: What is your current us by the incredible STEM your interest in pursuing a is needed to be qualified for role, and what all does professionals at Hasbro, career in the toy industry? your position? that encompass? Inc. who are dedicated to MELISSA HERSHEY: During MH: To work as a product MH: I work as an engineer “creating the world’s best college, I taught STEM to engineer for complex toys on the Integrated Play team play experiences.” middle school students it is useful to have a college at Hasbro. This team is a STEM Jobs spoke with using robotics. I enjoyed it so degree in mechanical fast-paced group of multi- Melissa Hershey, a senior much that after I graduated, engineering, electrical talented designers and engineer at Hasbro, to find I took a full-time job where I engineering or robotics. You engineers focused on a new out what goes into making developed and taught STEM need to have experience with wave of Hasbro products these iconic toys and games programs using a variety of creating models or projects that merge physical play and creating new classics for educational toys. -

Game Plan Classroom Activity Pack

Game Plan for Schools Classroom Activity Pack Developed by Make.Create.Innovate Introduction -How to use this Pack Game Plan is a touring exhibition from the Victoria and Albert Museum hosted by The Ark in 2019 Game Plan celebrates the joy, excitement (and occasional frustration) of playing board games. This free exhibition includes some of the most iconic, enthralling and visually striking games from the V&A’s outstanding collection.Game Plan features games from around the world, and also explores the important role of design. On display in the exhibition are current family favourites such as Cluedo and Trivial Pursuit, as well as traditional games like chess. The exhibition will also look at historical board games and beautifully designed games from the 18th and 19th centuries. Selected games are highlighted with a more detailed look at their history and influence. An early design of Monopoly before it was commercially mass produced will be one of the many fascinating exhibits on show. The Ark has commissioned this unique resource pack for teachers to extend the learning potential for students beyond their visit. There are three sections full of activities that guide teachers to facilitate STEAM-based learning through play, games development of design. Different levels and abilities are catered for within the pack so you may want to start at different sections depending on what is suitable for your class. Background Play is key for children as a means to develop an understanding of the world around them and to experiment with their role own in society through innovation, strategy, reflection and fun. -

Hasbro Introduces Trivial Pursuit Tap, Among First Games to Use Amazon Echo Buttons

Hasbro Introduces Trivial Pursuit Tap, Among First Games to Use Amazon Echo Buttons December 19, 2017 New Echo Buttons Bring Game-Show Style Competition to Iconic Game PAWTUCKET, R.I.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Today, gamers can test their trivia skills like never before with the launch of Trivial Pursuit Tap, an interactive game that brings together Amazon Alexa and Hasbro, Inc.'s (NASDAQ:HAS) iconic and popular trivia game. Amazon Echo Buttons are a simple but creative way for customers to play interactive games with their friends and Alexa, adding new and innovative methods of game play for beloved brands like Trivial Pursuit. Paired with the introduction of new Echo Buttons, Trivial Pursuit Tap provides a fun, game show-style competition with "buzzers" and all. Compete with friends to be the first to buzz in and answer questions from one of six categories. If you answer correctly, you can push your luck and attempt more questions. Each Echo Button connects via Bluetooth to a customers' compatible Echo device. The buttons illuminate and can be pressed to trigger a variety of multiplayer and single-player game experiences through Alexa skills. This innovative integration is timed perfectly to the holiday family gaming season, and is a first for Amazon and Trivial Pursuit. "This transformative, in-home technology will make Trivial Pursuit more animated and exciting than ever," said Jonathan Berkowitz, senior vice president of marketing for Hasbro Gaming. "At Hasbro Gaming, we're consistently working with the best minds both inside the company and beyond to create the world's best - and most unique - play experiences for our fans across the globe, and we're confident this collaboration with Amazon will do just that." "We're excited that customers can now play the iconic Trivial Pursuit game with Alexa," said Scott Van Vliet, Director, Amazon Alexa. -

Hasbro and Ubisoft® Teaming up to Bring Iconic Gaming Brands to Consoles

HASBRO AND UBISOFT® TEAMING UP TO BRING ICONIC GAMING BRANDS TO CONSOLES PARIS, FRANCE - August 7, 2013 – Today, Hasbro (NASDAQ: HAS) and Ubisoft (EURONEXT: UBI) announced that Ubisoft will develop and publish current and next-generation console games based on some of Hasbro’s most popular gaming brands, including MONOPOLY, SCRABBLE (in the United States and Canada only), TRIVIAL PURSUIT, RISK, BATTLESHIP and CRANIUM. “We look forward to collaborating with Ubisoft to offer consumers innovative new ways to experience their favorite gaming brands,” said Mark Blecher, Hasbro Senior Vice President and General Manager, Digital Gaming and Corporate Development. “Ubisoft’s leadership and expertise in the console gaming space will help support Hasbro’s strategy of bringing consumers engaging play experiences with our brands across multiple platforms.” “Hasbro makes games that we all know and love, and we’re thrilled to be able to work with them to create video game experiences based on some of their most popular brands.” said Geoffroy Sardin, EMEA Chief Marketing & Sales Officer. About Hasbro, Inc. Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS) is a branded play company dedicated to fulfilling the fundamental need for play for children and families through the creative expression of the Company’s world class brand portfolio, including TRANSFORMERS, MONOPOLY, PLAY-DOH, MY LITTLE PONY, MAGIC: THE GATHERING, NERF and LITTLEST PET SHOP. From toys and games, to television programming, motion pictures, digital gaming and a comprehensive licensing program, Hasbro strives to delight its global customers with innovative play and entertainment experiences, in a variety of forms and formats, anytime and anywhere. The Company's Hasbro Studios develops and produces television programming for more than 170 markets around the world, and for the U.S. -

Understanding Risk Through Board Games

The Mathematics Enthusiast Volume 12 Number 1 Numbers 1, 2, & 3 Article 8 6-2015 Understanding Risk Through Board Games Joshua T. Hertel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/tme Part of the Mathematics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hertel, Joshua T. (2015) "Understanding Risk Through Board Games," The Mathematics Enthusiast: Vol. 12 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/tme/vol12/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Mathematics Enthusiast by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TME, vol. 12, no. 1,2&3, p. 38 Understanding Risk Through Board Games Joshua T. Hertel University of Wisconsin–La Crosse, USA Abstract: In this article, I describe a potential avenue for investigating individual’s understanding of and reactions to risk using the medium of board games. I first discuss some challenges that researchers face in studying risk situations. Connecting to the existing probabilistic reasoning literature, I then present a rationale for using board games to model these situations. Following this, I draw upon intuition and dual-process theory to outline an integrated theoretical perspective for such investigations. The article concludes with two vignettes demonstrating how this perspective might be used to analyze thinking about risk in a board game setting. Keywords: risk, probabilistic reasoning, intuition, dual-process theory, board games. Within our information-driven society, understanding and making decisions about risk has become important for personal and professional success. -

Games to Play with the Cards

International House Game Rental List Volopoly Guesstures Zathura Trivial Pursuit 90’s Trivial Pursuit 80’s Trivial Pursuit Baby Boomer Edition Sudoku Game Deutschlandreise Sorry (wooden edition) Clue (wooden edition) Risk (wooden edition) 70th Anniversary Monopoly Settlers of Catan Balderdash Scattergories Travel Mahjong Sequence Game Clue Atlas in a Box Dutch Blitz Rook Operation: Simpsons Edition German Monopoly Pictionary Wooden Dominos Carcassonne Pax Britannica Axis and Allies Econtonos Parcheesi Sorry Regular Playing Cards Scooby-Doo Playing Cards Pirates of the Caribbean Playing Cards Poker Chips (3) Othello Ball & Jacks/Sticks UNO Deluxe Chess/Checker Combo Jenga Truth or Dare Settlers of Catan Expansion Pack Volopoly GO VOLS! Buy, sell and trade the University of Tennessee! Neyland Stadium, Andy Holt Tower, The Hill and Smokey are available at bargain basement prices! For a mere $110 you could become the newest member of the Pride of the Southland Marching Band! If things don�t go your way � you may be sent home on Academic Probation! VOLOPOLY is designed for alumni, students and fans of UT! Guesstures Guesstures is a new fast-action game from Hasbro that plays like a high-speed version of charades. Use gestures to help your team guess the word printed on the card. But you only have a few seconds and you can't say a word. When they guess correctly, grab your card before it gets swallowed up by the word-hungry Mimer-Timer. Second edition includes more cards and categories and provides quick word fun for everyone. Zathura Be the first player to reach the planet Zathura and you win! Trivial Pursuit 90’s America's favorite trivia game tackles one of the most momentous decades of the century with Trivial Pursuit 1990's Edition.