American Games: a Historical Perspective / by Bruce Whitehill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial Day Weekend Off Right with Hasbro Games at Home Or Away - You Won't Be Sorry!

May 27, 2010 Start Memorial Day Weekend off Right with Hasbro Games at Home or Away - You Won't Be Sorry! EAST LONGMEADOW, Mass., May 27, 2010 (BUSINESS WIRE) --According to AAA, more than 32 million travelers are expected to travel on vacation over Memorial Day weekend - a 5.4 percent increase from 2009. Whether traveling to beaches, camping grounds or U.S. attractions, Hasbro has your family fun covered! When packing, toss in some of Hasbro's newest games to keep everyone engaged and entertained on the open road, in the air, and once you've reached your final destination. "While the economy continues to be rocked by occasional waves of uncertainty, improved economic performance from one year ago should cause more Americans to take vacations this Memorial Day holiday," said Mary Yarber, Director, Program Management for AAA. "Whether traveling to see loved ones or exploring a new travel destination be sure to plan ahead for the most enjoyable vacation by taking advantage of AAA traveling planning tools and discounts on hotels, car rentals and attractions. Be sure to pack a vacation survival kit that includes activities for the whole family such as Hasbro games for enjoyable ways to pass time when traveling." A recent survey conducted by Hasbro found that American families plan to play games during time off this summer. Of those respondents planning a vacation, four in ten (41 percent) would rather have access to a closet full of board games than a big screen TV - talk about unplugged entertainment! If you don't have a game closet at your vacation destination, plan ahead and bring family games such as THE GAME OF LIFE, or CRANIUM. -

Ludopor – Platform for Creating Word Educational Games

LudoPor Word Games Creation Platform Samuel José Raposo Vieira Mira March of 2009 Acknowledgements While I have done a lot of work on this project, it would not have been possible without the help of many great people. I would like to thank my mother and my wonderful girlfriend who have encouraged me in everything I have ever done. I also owe a great amount to my thesis supervisor, Rui Prada whose advice and criticism has been critical in this project. Next I would like to thank the Ciberdúvidas community, especially Ana Martins, for having the time and will to try and experiment my prototypes. A special thanks is owed to my good friend António Leonardo and all the users that helped in this project especially the ones in the weekly meetings. 2 Abstract This thesis presents an approach for creating Word Games. We researched word games as Trivial Pursuit, Scrabble and more to establish reasons for their success. After this research we proposed a conceptual model using key concepts present in many of those games. The model defines the Game World with concepts such as the World Representation, Player, Challenges, Links, Goals and Performance Indicators. Then we created LudoPor - a prototype of a platform using some of the referred concepts. The prototype was made using an iterative design starting from paper prototypes to high fidelity prototypes using user evaluation tests to help define the right path. In this task we had the help of many users including persons of Ciberdúvidas (a Portuguese language community). Another objective of LudoPor was to create games for Ciberdúvidas that would be shown in their website. -

Clues About Bluffing in Clue: Is Conventional Wisdom Wise?

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Electrical Department of Electrical Engineering and Engineering and Computer Science Computer Science 2019 Clues About Bluffing in Clue: Is Conventional Wisdom Wise? David Hansen Kyle D. Hansen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eecs_fac Part of the Engineering Commons Clues About Bluffing in Clue : Is Conventional Wisdom Wise? David M. Hansen Affiliate Member, IEEE1, Kyle D. Hansen2 1College of Engineering, George Fox University, Newberg, OR, USA 2Westmont College, Santa Barabara, CA, USA We have used the board game Clue as a pedagogical tool in our course on Artificial Intelligence to teach formal logic through the development of logic-based computational game-playing agents. The development of game-playing agents allows us to experimentally test many game-play strategies and we have encountered some surprising results that refine “conventional wisdom” for playing Clue. In this paper we consider the effect of the oft-used strategy wherein a player uses their own cards when making suggestions (i.e., “bluffing”) early in the game to mislead other players or to focus on acquiring a particular kind of knowledge. We begin with an intuitive argument against this strategy together with a quantitative probabilistic analysis of this strategy’s cost to a player that both suggest “bluffing” should be detrimental to winning the game. We then present our counter-intuitive simulation results from playing computational agents that “bluff” against those that do not that show “bluffing” to be beneficial. We conclude with a nuanced assessment of the cost and benefit of “bluffing” in Clue that shows the strategy, when used correctly, to be beneficial and, when used incorrectly, to be detrimental. -

WO4 Ella Watts

Wooden Overcoats Funn Fragments – Autumn Cleaning © Wooden Overcoats Ltd. 2019 WOODEN OVERCOATS: FUNN FRAGMENTS “AUTUMN CLEANING” by GABRIELLE WATTS Antigone Funn ~ BETH EYRE Georgie Crusoe ~ CIARA BAXENDALE Rudyard Funn ~ FELIX TRENCH Dr. Bear ~ TOM CROWLEY FUNN FRAGMENTS THEME. ANNOUNCER: Funn Fragments... of Wooden Overcoats. Antigone struggles to let go in Autumn Cleaning by Gabrielle Watts. QUIET ROLL OF THUNDER, INTO: FUNN FUNERALS ATTIC. GEORGIE IS RIFLING THROUGH A MOUNTAIN OF JUNK. CRASHING AND CLUNKING AS SHE THROWS RANDOM OBJECTS OVER HER SHOULDER. GEORGIE: No… no… no… ANTIGONE IS DOWNSTAIRS. ANTIGONE: (OFF, MUFFLED) Georgie? GEORGIE: Don’t need that... don’t need that… ANTIGONE: (OFF, MUFFLED) Georgie! 1 Wooden Overcoats Funn Fragments – Autumn Cleaning © Wooden Overcoats Ltd. 2019 OFF, ANTIGONE HURRIEDLY RUNNING UP STEPS, UP TO THE ATTIC, AS GEORGIE KEEPS SORTING THROUGH JUNK. GEORGIE: They definitely don’t need that… THE TRAPDOOR BURSTS OPEN. ANTIGONE: (FROM OPEN TRAPDOOR) Georgie!! GEORGIE: Aaaargh! ANTIGONE: Aaaarghh! GEORGIE: (BEAT, RECOVERING) For… God’s sake, Antigone! You gave me a heart attack. Wait, why were you screaming? ANTIGONE: Because you were screaming! It’s frightening. Don’t do it again or you’re sacked. GEORGIE: You’re the one bursting through the trapdoor! ANTIGONE: Well you’re the one in the attic! Scuttling about and making a racket – I can hear it all the way from the mortuary! GEORGIE: Sorry about that. There isn’t a lot of space to move up here. ANTIGONE: You shouldn’t be up here at all! How many times have we told you that the attic is off-limits? GEORGIE: Yeah, I know that. -

Keep Kids Busy and Teach Real- World Skills with Board Games

Keep Kids Busy and Teach Real- World Skills with Board Games By Diane Nancarrow, MA, CCC-SLP KCC Director of Adolescent Programs If you’re hearing “I’m bored!” from your kids on a reg- ular basis, here’s an answer that sounds the same but is so much more fun: board games! Time at home with kids is a great opportunity to dust off those old games and remember the benefits of playing them as a family. Some extra benefits: Between smartphones, tablets, gaming systems and • Scrabble’s wooden tiles give wonderful tactile other devices, kids end up playing many games by pleasure. themselves. And let’s face it: pressing buttons on a • Trouble’s plastic dome forces a child to look and device is a lot easier than laying out a board, passing listen to the dice as they change. out money, moving your token, etc. • Chutes and Ladders teaches one-to-one corre- While many electronic games engage children in new spondence as kids move their markers and count and exciting ways, and some even involve physical the boxes. movement, board games also provide important learning opportunities. Since they are rarely complet- • Candy Land teaches colors. ed in a few short minutes, they encourage sustained • Monopoly encourages cooperation when choosing attention. Players must wait for others to complete who gets which iconic token. their turns while planning their own moves. • Parcheesi, Checkers, Sorry, and Aggravation teach When you play with your children, you help prepare turn-taking, strategy building, and patience. them to play with others. They will have the chance to respond to real people, watch facial expressions, body Board games appeal to our senses and are great to language, tone of voice, and the timing of their oppo- touch, see, and hear. -

The Monopolists Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the Worlds Favorite Board Game 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE MONOPOLISTS OBSESSION, FURY, AND THE SCANDAL BEHIND THE WORLDS FAVORITE BOARD GAME 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Pilon | 9781608199631 | | | | | The Monopolists Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the Worlds Favorite Board Game 1st edition PDF Book The Monopolists reveals the unknown story of how Monopoly came into existence, the reinvention of its history by Parker Brothers and multiple media outlets, the lost female originator of the game, and one man's lifelong obsession to tell the true story about the game's questionable origins. Expand the sub menu Film. Determined though her research may be, Pilon seems to make a point of protecting the reader from the grind of engaging these truths. More From Our Brands. We logged you out. This book allows a darker side of Monopoly. Cannot recommend it enough! Part journalist, part sleuth, Pilon exhausted five years researching the game's origin. Mary Pilon's page-turning narrative unravels the innocent beginnings, the corporate shenanigans, and the big lie at the center of this iconic boxed board game. For additional info see pbs. Courts slapped Parker Brothers down on those two games, ruling that the games were clearly in the public domain. Subscribe now Return to the free version of the site. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. After reading The Monopolists -part parable on the perils facing inventors, part legal odyssey, and part detective story-you'll never look at spry Mr. Open Preview See a Problem? The book is superlative journalism. Ralph Anspach, a professor fighting to sell his Anti-Monopoly board game decades later, unearthed the real story, which traces back to Abraham Lincoln, the Quakers, and a forgotten feminist named Lizzie Magie who invented her nearly identical Landlord's Game more than thirty years before Parker Brothers sold their version of Monopoly. -

Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, Being the Games Of

CO CD CO GAMES ANCIENT AND ORIENTAL AND HOW TO PLAY THEM. BEING THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS THE HIERA GRAMME OF THE GREEKS, THE LUDUS LATKUNCULOKUM OF THE ROMANS AND THE ORIENTAL GAMES OF CHESS, DRAUGHTS, BACKGAMMON AND MAGIC SQUAEES. EDWARD FALKENER. LONDON: LONGMANS, GEEEN AND Co. AND NEW YORK: 15, EAST 16"' STREET. 1892. All rights referred. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. PAGE, II. THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS. 9 Dr. Birch's Researches on the games of Ancient Egypt III. Queen Hatasu's Draught-board and men, now in the British Museum 22 IV. The of or the of afterwards game Tau, game Robbers ; played and called by the same name, Ludus Latrunculorum, by the Romans - - 37 V. The of Senat still the modern and game ; played by Egyptians, called by them Seega 63 VI. The of Han The of the Bowl 83 game ; game VII. The of the Sacred the Hiera of the Greeks 91 game Way ; Gramme VIII. Tlie game of Atep; still played by Italians, and by them called Mora - 103 CHESS. IX. Chess Notation A new system of - - 116 X. Chaturanga. Indian Chess - 119 Alberuni's description of - 139 XI. Chinese Chess - - - 143 XII. Japanese Chess - - 155 XIII. Burmese Chess - - 177 XIV. Siamese Chess - 191 XV. Turkish Chess - 196 XVI. Tamerlane's Chess - - 197 XVII. Game of the Maharajah and the Sepoys - - 217 XVIII. Double Chess - 225 XIX. Chess Problems - - 229 DRAUGHTS. XX. Draughts .... 235 XX [. Polish Draughts - 236 XXI f. Turkish Draughts ..... 037 XXIII. }\'ci-K'i and Go . The Chinese and Japanese game of Enclosing 239 v. -

Learning Board Game Rules from an Instruction Manual Chad Mills A

Learning Board Game Rules from an Instruction Manual Chad Mills A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science University of Washington 2013 Committee: Gina-Anne Levow Fei Xia Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Linguistics – Computational Linguistics ©Copyright 2013 Chad Mills University of Washington Abstract Learning Board Game Rules from an Instruction Manual Chad Mills Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Gina-Anne Levow Department of Linguistics Board game rulebooks offer a convenient scenario for extracting a systematic logical structure from a passage of text since the mechanisms by which board game pieces interact must be fully specified in the rulebook and outside world knowledge is irrelevant to gameplay. A representation was proposed for representing a game’s rules with a tree structure of logically-connected rules, and this problem was shown to be one of a generalized class of problems in mapping text to a hierarchical, logical structure. Then a keyword-based entity- and relation-extraction system was proposed for mapping rulebook text into the corresponding logical representation, which achieved an f-measure of 11% with a high recall but very low precision, due in part to many statements in the rulebook offering strategic advice or elaboration and causing spurious rules to be proposed based on keyword matches. The keyword-based approach was compared to a machine learning approach, and the former dominated with nearly twenty times better precision at the same level of recall. This was due to the large number of rule classes to extract and the relatively small data set given this is a new problem area and all data had to be manually annotated. -

History of the World Rulebook

TM RULES OF PLAY Introduction Components “With bronze as a mirror, one can correct one’s appearance; with history as a mirror, one can understand the rise and fall of a state; with good men as a mirror, one can distinguish right from wrong.” – Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty History of the World takes 3–6 players on an epic ride through humankind’s history. From the dawn of civilization to the twentieth century, you will witness humanity in all its majesty. Great minds work toward technological advances, ambitious leaders inspire their 1 Game Board 150 Armies citizens, and unpredictable calamities occur—all amid the rise and fall (6 colors, 25 of each) of empires. A game consists of five epochs of time, in which players command various empires at the height of their power. During your turn, you expand your empire across the globe, gaining points for your conquests. Forge many a prosperous empire and defeat your adversaries, for at the end of the game, only the player with the most 24 Capitols/Cities 20 Monuments (double-sided) points will have his or her immortal name etched into the annals of history! Catapult and Fort Assembly Note: The lighter-colored sides of the catapult should always face upward and outward. 14 Forts 1 Catapult Egyptians Ramesses II (1279–1213 BCE) WEAPONRY I EPOCH 4 1500–450 BCE NILE Sumerians 3 Tigris – Empty Quarter Egyptians 4 Nile Minoans 3 Crete – Mediterranean Sea Hittites 4 Anatolia During this turn, when you fight a battle, Assyrians 6 Pyramids: Build 1 monument for every Mesopotamia – Empty Quarter 1 resource icon (instead of every 2). -

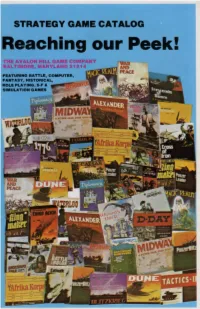

Ah-80Catalog-Alt

STRATEGY GAME CATALOG I Reaching our Peek! FEATURING BATTLE, COMPUTER, FANTASY, HISTORICAL, ROLE PLAYING, S·F & ......\Ci l\\a'C:O: SIMULATION GAMES REACHING OUR PEEK Complexity ratings of one to three are introduc tory level games Ratings of four to six are in Wargaming can be a dece1v1ng term Wargamers termediate levels, and ratings of seven to ten are the are not warmongers People play wargames for one advanced levels Many games actually have more of three reasons . One , they are interested 1n history, than one level in the game Itself. having a basic game partlcularly m1l11ary history Two. they enroy the and one or more advanced games as well. In other challenge and compet111on strategy games afford words. the advance up the complexity scale can be Three. and most important. playing games is FUN accomplished within the game and wargaming is their hobby The listed playing times can be dece1v1ng though Indeed. wargaming 1s an expanding hobby they too are presented as a guide for the buyer Most Though 11 has been around for over twenty years. 11 games have more than one game w1th1n them In the has only recently begun to boom . It's no [onger called hobby, these games w1th1n the game are called JUSt wargam1ng It has other names like strategy gam scenarios. part of the total campaign or battle the ing, adventure gaming, and simulation gaming It game 1s about Scenarios give the game and the isn 't another hoola hoop though. By any name, players variety Some games are completely open wargam1ng 1s here to stay ended These are actually a game system. -

View from the Trenches Avalon Hill Sold!

VIEW FROM THE TRENCHES Britain's Premier ASL Journal Issue 21 September '98 UK £2.00 US $4.00 AVALON HILL SOLD! IN THIS ISSUE HIT THE BEACHES RUNNING - Seaborne assaults for beginners SAVING PRIVATE RYAN - Spielberg's New WW2 Movie LANDING CRAFT FLOWCHART - LC damage determination made easy GOLD BEACH - UK D-Day Convention report IN THIS ISSUE PREP FIRE Hello and welcome the latest issue of View From The Trenches. PREP FIRE 2 The issue is slightly bigger than normal due to Greg Dahl’s AVALON HILL SOLD 3 excellent but rather large article and accompanying flowchart dealing with beach assaults. Four extra pages for the same price. Can’t be INCOMING 4 bad. SCOTLAND THE BRAVE 5 In keeping with the seaborne theme there is also a report on the replaying of the Monster Scenarios ‘Gold Beach’ scenario in the D-DAY AT GOLD BEACH 6 D-Day museum in June, and a review of the new Steve Spielberg WW2 movie, Saving Private Ryan. HIT THE BEACHES RUNNING! 7 I hope to be attending ASLOK this year, so I’m not sure if the “THIS IS THE CALL TO ARMS!” 9 next issue will be out at INTENSIVE FIRE yet. If not, it’ll be out soon after IF’98. THE CRUSADERS 12 While on the subject of conventions, if anyone is planning on SAVING PRIVATE RYAN 18 attending the German convention GRENADIER ’98 please get in touch with me. If we can get enough of us to go as a group, David ON THE CONVENTION TRAIL 19 Schofield may be able to organise transport for all us. -

Parker Brothers Real Estate Trading Game in 1934, Charles B

Parker Brothers Real Estate Trading Game In 1934, Charles B. Darrow of Germantown, Pennsylvania, presented a game called MONOPOLY to the executives of Parker Brothers. Mr. Darrow, like many other Americans, was unemployed at the time and often played this game to amuse himself and pass the time. It was the game’s exciting promise of fame and fortune that initially prompted Darrow to produce this game on his own. With help from a friend who was a printer, Darrow sold 5,000 sets of the MONOPOLY game to a Philadelphia department store. As the demand for the game grew, Darrow could not keep up with the orders and arranged for Parker Brothers to take over the game. Since 1935, when Parker Brothers acquired the rights to the game, it has become the leading proprietary game not only in the United States but throughout the Western World. As of 1994, the game is published under license in 43 countries, and in 26 languages; in addition, the U.S. Spanish edition is sold in another 11 countries. OBJECT…The object of the game is to become the wealthiest player through buying, renting and selling property. EQUIPMENT…The equipment consists of a board, 2 dice, tokens, 32 houses and 12 hotels. There are Chance and Community Chest cards, a Title Deed card for each property and play money. PREPARATION…Place the board on a table and put the Chance and Community Chest cards face down on their allotted spaces on the board. Each player chooses one token to represent him/her while traveling around the board.