Synchrony in the New World: an Example of Archaeoethnology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum Pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, Or Independent Domestication

KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History ISSN: 0023-1940 (Print) 2051-6177 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ykiv20 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy To cite this article: Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy (2017): A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication, KIVA, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ykiv20 Download by: [184.99.134.102] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 06:14 kiva, 2017, 1–29 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham1, Karen R. Adams2, Susan J. Smith3, and Terence M. Murphy4 1 Department of Anthropology and Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB # 3115, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA, [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Archaeobotanical Consultant, 2837 E. Beverly Dr., Tucson, AZ 85716, USA 3 Consulting Archaeopalynologist, 8875 Carefree Ave., Flagstaff, AZ 86004, USA 4 Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Little Barley Grass (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) is a well-known native food do- mesticated in the U.S. -

KNOTLESS NETTING in AMERICA and OCEANIA T HE Question Of

116 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST [N. s., 37, 1935 48. tcdbada'b stepson, stepdaughter, son or KNOTLESS NETTING IN AMERICA daughter of wife's brother or sis AND OCEANIA By D. S. DAVIDSON ter, son or daughter of husband's brother or sister: reciprocal to the HE question of trans-Pacific influences in American cultureshas been two preceding terms 49. tcdtsa'pa..:B T seriously debated for a number of years. Those who favor a trans step~grandfather, husband of oceanic movement have pointed out many resemblances and several grandparent's'sister 50. tCLlka 'yaBB striking similarities between certain culture traits of the New World and step-grandmother, wife of grand Oceania. The theory of a historical relationship between these appearances parent's brother 51. tcde'batsal' is based upon the hypothesis that independent invention and convergence step-grandchild, grandchild of speaker's wife's (or speaker's hus in development are not reasonable explanations either for the great number band's) brother or sister: recipro of resemblances or for the certain complexities found in the two areas. c~l to the two preceding terms The well-known objections to the trans-Pacific diffusion theory can 52. tsi.J.we'bats husband Or wife of grandchild of be summarized as follows: speaker or speaker's brother or 1. That many of the so-called similarities at best are only resemblances sister; term possibly reciprocal between very simple traits which might be independently invented or 53. tctlsxa'xaBll son-in-law or daughter-in-law of discovered. speaker's wife's brother or sister, 2. -

Asia's Rise in the New World Trade Order

GED Study Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order The Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements on Asian Countries Part 2 of the GED Study Series: Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements Authors Dr. Cora Jungbluth (Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh), Dr. Rahel Aichele (ifo, München), Prof. Gabriel Felbermayr, PhD (ifo and LMU, München) GED Study Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order The Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements on Asian Countries Part 2 of the GED Study Series: Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order Table of contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction: Mega-regionals and the new world trade order 6 2. Asia in world trade: A look at the “noodle bowl” 10 3. Mega-regionals in the Asia-Pacific region and their effects on Asian countries 14 3.1 The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): The United States’ “pivot to Asia” in trade 14 3.2 The Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP): An inclusive alternative? 16 3.3 The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP): The ASEAN initiative 18 4. Case studies 20 4.1 China: The world’s leading trading nation need not fear the TPP 20 4.2 Malaysia: The “Asian Tiger Cub” profits from deeper transpacific integration 22 5. Parallel scenarios: Asian-Pacific trade deals as counterweight to the TTIP 25 6. Conclusion: Asia as the driver for trade integration in the 21st century 28 Appendix 30 Bibliography 30 List of abbreviations 34 List of figures 35 List of tables 35 List of the 20 Asian countries included in our analysis 36 Links to the fact sheets of the 20 Asian countries included in our analysis 37 About the authors 39 Imprint 39 4 Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order Executive summary Asia is one of the most dynamic regions in the world and the FTAAP, according to our calculations the RCEP also has the potential to become the key region in world trade has positive economic effects for most countries in Asia, in the 21st century. -

Two Centuries of International Migration

IZA DP No. 7866 Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Timothy J. Hatton December 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Northwestern University Timothy J. Hatton University of Essex, Australian National University and IZA Discussion Paper No. 7866 December 2013 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

Mummies and Mummification Practices in the Southern and Southwestern United States Mahmoud Y

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 1998 Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States Mahmoud Y. El-Najjar Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan Thomas M. J. Mulinski Chicago, Illinois Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard El-Najjar, Mahmoud Y.; Mulinski, Thomas M. J.; and Reinhard, Karl, "Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States" (1998). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in MUMMIES, DISEASE & ANCIENT CULTURES, Second Edition, ed. Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn, and Theodore A. Reyman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 7 pp. 121–137. Copyright © 1998 Cambridge University Press. Used by permission. Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States MAHMOUD Y. EL-NAJJAR, THOMAS M.J. MULINSKI AND KARL J. REINHARD Mummification was not intentional for most North American prehistoric cultures. Natural mummification occurred in the dry areas ofNorth America, where mummies have been recovered from rock shelters, caves, and over hangs. In these places, corpses desiccated and spontaneously mummified. In North America, mummies are recovered from four main regions: the south ern and southwestern United States, the Aleutian Islands, and the Ozark Mountains ofArkansas. -

Conerence Entitled "Understanding Population Change: *United States

AUTHOR Roseman-, Curti And Others TITLE Population Redistribution in the Mi wes INSTITUTION North 'central Regional Center for Ru al Development Ames,. Iowa. 1PONS -AGENgY --Department-of Agriculture, WashingtoA C. PUB DATE Nay 81 . NOTE 22BR.: 'Papers were ofiginally presented at a conerence entitled "Understanding Population Change: Issuei and Consequences of Population Redistribution ' in the Midwest" (Champaign, IL, Birch 12, 1979). EDPS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Decentraliiation: *Demography: Employment Patterns: Geography: Indubtry: Land Use: Migrants: *Migration' Patterns: Politics: *Population Distribution: Public Policy: Research Needs: *Rural Ardasi *Urban to Rural Migtation IDENTIFI *United States (Midwest ABSTRACT The-ninechapter0-in the book f4dus on the 1970s' metropolitan to-4nOnmetropolitan migration stream and address both population -patterns and`'-prooesses and the impacts and policy issues associated with the result-in-q, popUlation'redistribution in the Midwest. Peter A. Morrison places the Midwest in the national context of changing population structure and redistribution. John R Borchert traces the,Ilistorical and geographic forCeS which have shaped the 'current'patterts.:CalvinL.. Bealeand Glenn V. Fuguittfocus. on deiographicaspedtt Mf,redistribution'in.W Midwest. Ralph R. 'lifter' and Richard W. Buxbaum place Midwest trends in a policy context. Andrew J. Sofranko, James D. Williams, and prederick C. Fliegel disduss. a survey offecent migrantS to fastzgrowing Midwest' nonmetropolitan areas. RiehardLonsdale documents the decentralization trend in manufacturing employment and. its role, in population redistribution. David Bdtry-examinesthe:significance-of land cOnverSton:from rural to 'urban uses. Alvin D. Sokolov addresses - the localpolitical implications\of recent small town growth. ,Laurence S. ROsen.outlines and analyzes methods and data needed for population pitolectiOns.-- fAuthOt,SEI --_*****#****** ********. -

Explorers of Africa

Explorers of Africa Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460) Portugal Goals of exploration: establish a Christian empire in western Africa find new sources of gold create maps of the African coast Trips funded by Henry the Navigator led to more Impact: exploration of western Africa Bartolomeu Días (1450-1500) Portugal Rounded the southernmost tip of Africa in 1488 Goal of exploration: find a water route to Asia Impact: Led the Portuguese closer to discovering a water route to Asia Vasco da Gama (1460s-1524) Portugal Rounded the southernmost tip of Africa; Reached India in 1498 Goal of exploration: find a water route to Asia Found a water route to Asia and brought back Impact: jewels and spices, which encouraged further exploration Explorers of the Caribbean Christopher Columbus (1450-1506) Spain In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue (He sailed again in 1493, 1498, and 1502) Goal of exploration: find a water route to Asia Discovered the New World and led to Impact: exploration of the Americas Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475-1519) Spain Discovered the Pacific Ocean and the Isthmus of Panama in 1513 Goal of exploration: further exploration of the New World Discovered the Pacific Ocean and a new Impact: passage for exploration Explorers of South America Ferdinand Magellan Spain (1480-1521) Magellan's ships completed the first known circumnavigation of the globe. Goal of exploration: find a water route to Asia across the Pacific Discovered a new passage between the Impact: Atlantic and Pacific Oceans Francisco Pizarro Spain (1470s-1541) Conquered -

Potential Distribution of the Invasive Old World Climbing Fern, Lygodium Microphyllum in North and South America

1 Running title: Potential distribution of invasive fern Potential distribution of the invasive Old World climbing fern, Lygodium microphyllum in North and South America John A. Goolsby, United States Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Australian Biological Control Laboratory, CSIRO Long Pocket Laboratories, 120 Meiers Rd. Indooroopilly, Queensland, Australia 4068 email: [email protected] 2100 words 2 Abstract: The climate matching program CLIMEX is used to predict the potential distribution of the fern, Lygodium microphyllum in North and South America, with particular reference to Florida, USA where it is invasive. A predictive model was fitted to express the known distribution of the fern. Several new collection locations were incorporated into the model based on surveys for the plant near its ecoclimatic limits in China and Australia. The model predicts that the climate is suitable for further expansion of L. microphyllum north into central Florida. Large parts of the Caribbean, Central and South America are also at risk. Index terms: Invasive species, weeds, Florida Everglades, predictive modeling, CLIMEX. INTRODUCTION Lygodium microphyllum (Cav.) R. Br. (Lygodiaceae, Pteridophyta), the Old World climbing fern, is native to the Old World wet tropics and subtropics of Africa, Asia, Australia, and Oceania (Pemberton 1998). It is an aggressive invasive weed in southern Florida, USA (Pemberton and Ferriter 1998) and is classified as a Category I invasive species by the Florida Exotic Plant Pest Council (Langeland and Craddock Burks 1998). It was first found to be naturalized in Florida 1965; however, its rapid spread is now a serious concern because of its dominance over native vegetation. -

The Long-Term Effects of Africa's Slave Trades

THE LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF AFRICA’S SLAVE TRADES* NATHAN NUNN Can part of Africa’s current underdevelopment be explained by its slave trades? To explore this question, I use data from shipping records and histori- cal documents reporting slave ethnicities to construct estimates of the number of slaves exported from each country during Africa’s slave trades. I find a robust negative relationship between the number of slaves exported from a country and current economic performance. To better understand if the relationship is causal, I examine the historical evidence on selection into the slave trades and use in- strumental variables. Together the evidence suggests that the slave trades had an adverse effect on economic development. I. INTRODUCTION Africa’s economic performance in the second half of the twen- tieth century has been poor. One, often informal, explanation for Africa’s underdevelopment is its history of extraction, character- ized by two events: the slave trades and colonialism. Bairoch (1993, p. 8) writes that “there is no doubt that a large number of negative structural features of the process of economic under- development have historical roots going back to European col- onization.” Manning (1990, p. 124) echoes Bairoch but focuses on the slave trades, writing, “Slavery was corruption: it involved theft, bribery, and exercise of brute force as well as ruses. Slavery thus may be seen as one source of precolonial origins for modern corruption.” Recent empirical studies suggest that Africa’s history can explain part of its current underdevelopment. These studies fo- cus on the link between countries’ colonial experience and cur- rent economic development (Grier 1999; Englebert 2000a, 2000b; * A previous version of this paper was circulated under the title “Slavery, Insti- tutional Development, and Long-Run Growth in Africa.” I am grateful to the editor, Edward Glaeser, and three anonymous referees for comments that substantially improved this paper. -

THE LIMITS of SELF-DETERMINATION in OCEANIA Author(S): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol

THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Author(s): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol. 56, No. 1/2, The Caribbean and Pacific in a New World Order (March/June 2007), pp. 182-208 Published by: Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, University of the West Indies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27866500 . Accessed: 11/10/2013 20:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of the West Indies and Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social and Economic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 133.30.14.128 on Fri, 11 Oct 2013 20:07:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Social and Economic Studies 56:1&2 (2007): 182-208 ISSN:0037-7651 THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Terence Wesley-Smith* ABSTRACT This article surveys processes of decolonization and political development inOceania in recent decades and examines why the optimism of the early a years of self government has given way to persistent discourse of crisis, state failure and collapse in some parts of the region. -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

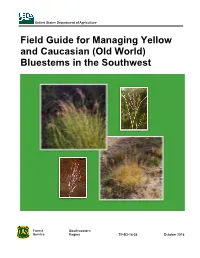

Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest

USDA United States Department of Agriculture - Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest Forest Southwestern Service Region TP-R3-16-36 October 2018 Cover Photos Top left — Yellow bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Top right — Yellow bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Billy Warrick; Soil, Crop and More Information Lower left — Caucasian bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Lower right — Caucasian bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Authors Karen R. Hickman — Professor, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater OK Keith Harmoney — Range Scientist, KSU Ag Research Center, Hays KS Allen White — Region 3 Pesticides/Invasive Species Coord., Forest Service, Albuquerque NM Citation: USDA Forest Service. 2018. Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest. Southwestern Region TP-R3-16-36, Albuquerque, NM. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339.