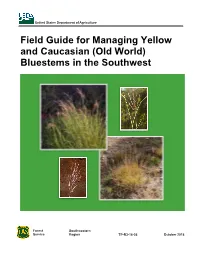

Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum Pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, Or Independent Domestication

KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History ISSN: 0023-1940 (Print) 2051-6177 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ykiv20 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy To cite this article: Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy (2017): A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication, KIVA, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ykiv20 Download by: [184.99.134.102] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 06:14 kiva, 2017, 1–29 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham1, Karen R. Adams2, Susan J. Smith3, and Terence M. Murphy4 1 Department of Anthropology and Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB # 3115, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA, [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Archaeobotanical Consultant, 2837 E. Beverly Dr., Tucson, AZ 85716, USA 3 Consulting Archaeopalynologist, 8875 Carefree Ave., Flagstaff, AZ 86004, USA 4 Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Little Barley Grass (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) is a well-known native food do- mesticated in the U.S. -

Soil Response to Cropping Sequences and Grazing Under Integrated Crop-Livestock System Hanxiao Feng South Dakota State

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Theses and Dissertations 2017 Soil Response to Cropping Sequences and Grazing Under Integrated Crop-livestock System Hanxiao Feng South Dakota State Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, and the Soil Science Commons Recommended Citation Feng, Hanxiao, "Soil Response to Cropping Sequences and Grazing Under Integrated Crop-livestock System" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2160. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/2160 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOIL RESPONSE TO CROPPING SEQUENCES AND GRAZING UNDER INTEGRATED CROP-LIVESTOCK SYSTEM BY HANXIAO FENG A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Master of Science Major in Plant Science South Dakota State University 2017 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Foremost, I would like to express my grateful thanks to my advisor, Dr. Sandeep Kumar for his continuous encouragement, useful suggestion, great patience, and excellent guidance throughout the whole study process. Without his support and help, careful review, and critical recommendation on several versions of this thesis manuscript, I could not finish this paper and my MS degree. I would also like to offer my sincere gratitude to all committee members, Dr. Shannon Osborne, Dr. -

Grass Genera in Townsville

Grass Genera in Townsville Nanette B. Hooker Photographs by Chris Gardiner SCHOOL OF MARINE and TROPICAL BIOLOGY JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY TOWNSVILLE QUEENSLAND James Cook University 2012 GRASSES OF THE TOWNSVILLE AREA Welcome to the grasses of the Townsville area. The genera covered in this treatment are those found in the lowland areas around Townsville as far north as Bluewater, south to Alligator Creek and west to the base of Hervey’s Range. Most of these genera will also be found in neighbouring areas although some genera not included may occur in specific habitats. The aim of this book is to provide a description of the grass genera as well as a list of species. The grasses belong to a very widespread and large family called the Poaceae. The original family name Gramineae is used in some publications, in Australia the preferred family name is Poaceae. It is one of the largest flowering plant families of the world, comprising more than 700 genera, and more than 10,000 species. In Australia there are over 1300 species including non-native grasses. In the Townsville area there are more than 220 grass species. The grasses have highly modified flowers arranged in a variety of ways. Because they are highly modified and specialized, there are also many new terms used to describe the various features. Hence there is a lot of terminology that chiefly applies to grasses, but some terms are used also in the sedge family. The basic unit of the grass inflorescence (The flowering part) is the spikelet. The spikelet consists of 1-2 basal glumes (bracts at the base) that subtend 1-many florets or flowers. -

Ethnobotanical Usages of Grasses in Central Punjab-Pakistan

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 9, September-2013 452 ISSN 2229-5518 Ethnobotanical Usages of Grasses in Central Punjab-Pakistan Arifa Zereen, Tasveer Zahra Bokhari & Zaheer-Ud-Din Khan ABSTRACT- Poaceae (Gramineae) constitutes the second largest family of monocotyledons, having great diversity and performs an important role in the lives of both man and animals. The present study was carried out in eight districts (viz., Pakpattan, Vehari, Lahore, Nankana Sahib, Faisalabad, Sahiwal, Narowal and Sialkot) of Central Punjab. The area possesses quite rich traditional background which was exploited to get information about ethnobotanical usage of grasses. The ethnobotanical data on the various traditional uses of the grasses was collected using a semi- structured questionnaire. A total of 51 species of grasses belonging to 46 genera were recorded from the area. Almost all grasses were used as fodder, 15% were used for medicinal purposes in the area like for fever, stomach problems, respiratory tract infections, high blood pressure etc., 06% for roof thatching and animal living places, 63% for other purposes like making huts, chicks, brooms, baskets, ladders stabilization of sand dunes. Index Terms: Ethnobotany, Grasses, Poaceae, Fodder, Medicinal Use, Central Punjab —————————— —————————— INTRODUCTION Poaceae or the grass family is a natural homogenous group purposes. Chaudhari et al., [9] studied ethnobotanical of plants, containing about 50 tribes, 660 genera and 10,000 utilization of grasses in Thal Desert, Pakistan. During this species [1], [2]. In Pakistan Poaceae is represented by 158 study about 29 species of grasses belonging to 10 tribes genera and 492 species [3].They are among the most were collected that were being utilized for 10 different cosmopolitan of all flowering plants. -

Santa Rita Experimental Range: 100 Years (1903 to 2003) of Accomplishments and Contributions; Conference Proceedings; 2003 October 30–November 1; Tucson, AZ

Michael A. Crimmins Theresa M. Mau-Crimmins Climate Variability and Plant Response at the Santa Rita Experimental Range, Arizona Abstract: Climatic variability is reflected in differential establishment, persistence, and spread of plant species. Although studies have investigated these relationships for some species and functional groups, few have attempted to characterize the specific sequences of climatic conditions at various temporal scales (subseasonal, seasonal, and interannual) associated with proliferation of particular species. Research has primarily focused on the climate conditions concurrent with or occurring just prior to a vegetation response. However, the cumulative effect of antecedent conditions taking place for several consecutive seasons may have a greater influence on plant growth. In this study, we tested whether the changes in overall cover of plant species can be explained by antecedent climate conditions. Temperature, precipitation, and Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) values at various lags were correlated with cover. PDSI had the strongest correlations for several drought-intolerant species at lags up to six seasons prior to the sampling date. Precipita- tion, surprisingly, did not correlate with species cover as strongly as PDSI. This is attributed to PDSI capturing soil moisture conditions, which are important to plant growth, better than raw precipi- tation measurements. Temperature correlations were weak and possessed little explanatory power as predictors of species cover. Acknowledgments: Data sets were provided by the Santa Rita Experimental Range Digital Database. Funding for the digitization of these data was provided by the USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station and the University of Arizona. Introduction ______________________________________________________ Climatic variability is reflected in differential establishment, persistence, and spread of plant species. -

Plant Associations and Descriptions for American Memorial Park, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Saipan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation Inventory Project American Memorial Park Natural Resource Report NPS/PACN/NRR—2013/744 ON THE COVER Coastal shoreline at American Memorial Park Photograph by: David Benitez Vegetation Inventory Project American Memorial Park Natural Resource Report NPS/PACN/NRR—2013/744 Dan Cogan1, Gwen Kittel2, Meagan Selvig3, Alison Ainsworth4, David Benitez5 1Cogan Technology, Inc. 21 Valley Road Galena, IL 61036 2NatureServe 2108 55th Street, Suite 220 Boulder, CO 80301 3Hawaii-Pacific Islands Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (HPI-CESU) University of Hawaii at Hilo 200 W. Kawili St. Hilo, HI 96720 4National Park Service Pacific Island Network – Inventory and Monitoring PO Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 5National Park Service Hawaii Volcanoes National Park – Resources Management PO Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 December 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

A New Species of Bothriochloa (Poaceae, Andropogoneae) Endemic to Montane Grasslands of Santa Catarina, Brazil

Phytotaxa 183 (1): 044–050 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.183.1.5 A new species of Bothriochloa (Poaceae, Andropogoneae) endemic to montane grasslands of Santa Catarina, Brazil 1 1 EMILAINE BIAVA DALMOLIM & ANA ZANIN 1 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia de Fungos, Algas e Plantas, Departamento de Botânica, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Campus Trindade, 88040-900, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Email: [email protected] Abstract Bothriochloa catharinensis, a new species of Andropogoneae (Poaceae: Panicoideae, Andropogoneae) endemic to mon- tane grasslands associated with araucaria forest in the state of Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil, is described and illustrated. Morphological similarities between the new taxon and other species of Bothriochloa are discussed. Comments on habitat, morphology, distribution and conservation status are provided. Key words: araucaria forest, grasses, Panicoideae, SEM, taxonomy Resumo Bothriochloa catharinensis, uma nova espécie de Poaceae considerada endêmica de campos de altitude associados à Floresta Ombró- fila Mista (floresta com araucária) do Estado de Santa Catarina, Sul do Brasil, é aqui descrita e ilustrada. Similaridades morfológicas entre a nova espécie e outros táxons de Bothriochloa são discutidas. São fornecidos dados sobre hábitat, morfologia, distribuição e estado de conservação. Palavras chave: Floresta Ombrófila Mista, gramíneas, MEV, Panicoideae, taxonomia Introduction Bothriochloa Kuntze (1891: 762) comprises about 40 species distributed largely in warm-temperate areas of the world (Scrivanti et al. 2009). In the Americas, the genus is represented by about 27 species widely distributed in tropical, temperate and subtropical regions; four of these have been cultivated and naturalized (Vega 2000, Vega & Scrivanti 2012). -

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Daniel G. Milchunas General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-169 April 2006 Milchunas, Daniel G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p. Abstract Grazing by wild and domestic mammals can have small to large effects on plant communities, depend- ing on characteristics of the particular community and of the type and intensity of grazing. The broad objective of this report was to extensively review literature on the effects of grazing on 25 plant commu- nities of the southwestern U.S. in terms of plant species composition, aboveground primary productiv- ity, and root and soil attributes. Livestock grazing management and grazing systems are assessed, as are effects of small and large native mammals and feral species, when data are available. Emphasis is placed on the evolutionary history of grazing and productivity of the particular communities as deter- minants of response. After reviewing available studies for each community type, we compare changes in species composition with grazing among community types. Comparisons are also made between southwestern communities with a relatively short history of grazing and communities of the adjacent Great Plains with a long evolutionary history of grazing. Evidence for grazing as a factor in shifts from grasslands to shrublands is considered. An appendix outlines a new community classification system, which is followed in describing grazing impacts in prior sections. -

Introductory Grass Identification Workshop University of Houston Coastal Center 23 September 2017

Broadleaf Woodoats (Chasmanthium latifolia) Introductory Grass Identification Workshop University of Houston Coastal Center 23 September 2017 1 Introduction This 5 hour workshop is an introduction to the identification of grasses using hands- on dissection of diverse species found within the Texas middle Gulf Coast region (although most have a distribution well into the state and beyond). By the allotted time period the student should have acquired enough knowledge to identify most grass species in Texas to at least the genus level. For the sake of brevity grass physiology and reproduction will not be discussed. Materials provided: Dried specimens of grass species for each student to dissect Jewelry loupe 30x pocket glass magnifier Battery-powered, flexible USB light Dissecting tweezer and needle Rigid white paper background Handout: - Grass Plant Morphology - Types of Grass Inflorescences - Taxonomic description and habitat of each dissected species. - Key to all grass species of Texas - References - Glossary Itinerary (subject to change) 0900: Introduction and house keeping 0905: Structure of the course 0910: Identification and use of grass dissection tools 0915- 1145: Basic structure of the grass Identification terms Dissection of grass samples 1145 – 1230: Lunch 1230 - 1345: Field trip of area and collection by each student of one fresh grass species to identify back in the classroom. 1345 - 1400: Conclusion and discussion 2 Grass Structure spikelet pedicel inflorescence rachis culm collar internode ------ leaf blade leaf sheath node crown fibrous roots 3 Grass shoot. The above ground structure of the grass. Root. The below ground portion of the main axis of the grass, without leaves, nodes or internodes, and absorbing water and nutrients from the soil. -

Bothriochloa Insculpta Scientific Name Bothriochloa Insculpta (Hochst

Tropical Forages Bothriochloa insculpta Scientific name Bothriochloa insculpta (Hochst. ex A. Rich.) A. Camus Strongly stoloniferous cv. Bisset (L); weakly stoloniferous cv. Hatch (R) Synonyms Basionym: Andropogon insculptus Hochst. ex A. Rich.; Andropogon pertusus (L.) Willd. var. insculptus (Hochst. A perennial tussock, often strongly or ex A. Rich.) Hack.; Dichanthium insculptum (Hochst. ex weakly stoloniferous (cv. Bisset) A. Rich.) Clayton Family/tribe Family: Poaceae (alt. Gramineae) subfamily: Panicoideae tribe: Andropogoneae. Morphological description Pink to mauve stolons (cv. Bisset) A perennial tussock, 30‒80 cm tall (‒1.5 m at maturity); Dense flowering in seed crop (cv. Bisset) often strongly or weakly stoloniferous; stolons 1.5‒2.5 mm diameter, reddish pink to mauve. Leaves glaucous; leaf blades linear, tapering, to 30 cm long and 8 mm wide, mostly glabrous except for spreading hairs at the base; ligule a fringed membrane, hairs shorter than the membrane. Culm internodes yellow, nodes with annulus of spreading white hairs, to 4 mm long. Inflorescence subdigitate or with a central axis seldom over 3 cm long; 3 to >20 racemes per panicle, 2‒9 cm long, olive green to purplish in colour, lower racemes often branched. Spikelets in pairs, sessile spikelet with single deep pit, and geniculate and twisted awn 15‒25 mm long in the Inflorescence subdigitate or with a Seed units with pits in the lower glume. lower glume; pedicellate spikelet glabrous, unawned, central axis seldom over 3 cm long; 3 to usually neuter, with 1‒3 pits in the lower glume. >20 racemes per panicle. Inflorescence, seed and leaves emit an aromatic odour when crushed. -

PASTURES: Mackay Whitsunday Region

Queensland the Smart State PASTURES: Mackay Whitsunday region A guide for developing productive and sustainable pasture-fed grazing systems PASTURES: Mackay Whitsunday region A guide for developing productive and sustainable pasture-fed grazing systems Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries ii PASTURES: Mackay Whitsunday region Many people have provided and Many photos contained in this book assisted with information contained in were sourced from Tropical Forages: this book. Thanks to the many Mackay an interactive selection tool (Cook, Whitsunday property owners, graziers B.G., Pengelly, B.C., Brown, S.D., and managers who have worked with Donnelly, J.L., Eagles, D.A., Franco, DPI&F over the past decades to trial, M.A., Hanson, J., Mullen, B.F., understand and develop successful Partridge, I.J., Peters, M. and Schultze- pasture technologies for productive Kraft, R. 2005. Tropical Forages: an and sustainable pasture-fed grazing interactive selection tool, [CD-ROM], systems. CSIRO, DPI&F (Qld), CIAT and ILRI, Brisbane, Australia). Thanks to Mick Quirk, Science Leader (Sustainable Grazing Systems) Additional photos have been provided within DPI&F Animal Science, for by Terry Hilder, Caroline Sandral, Paul his support and encouragement with Wieck, and Christine Peterson. this project. I gratefully acknowledge Acknowledgements the financial support provided by the Mackay Whitsunday Natural Resource Management Group (MWNRMG). Thanks to Kelly Flower and Vivienne Dwyer (MWNRM Group Inc.), Tanya Radke and Lee Cross (DPI&F) for their assistance in organising the agreement between DPI&F and MWNRM Group Inc. Special thanks to those people who have given of their time to review and comment on early and progressive drafts; in particular John Hopkinson, John Hughes, Kendrick Cox, Ross Dodt, Terry Hilder, Caroline Sandral, Bill Schulke (DPI&F) and Nigel Onley (Consultant). -

Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest

USDA United States Department of Agriculture - Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest Forest Southwestern Service Region TP-R3-16-36 October 2018 Cover Photos Top left — Yellow bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Top right — Yellow bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Billy Warrick; Soil, Crop and More Information Lower left — Caucasian bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Lower right — Caucasian bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Authors Karen R. Hickman — Professor, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater OK Keith Harmoney — Range Scientist, KSU Ag Research Center, Hays KS Allen White — Region 3 Pesticides/Invasive Species Coord., Forest Service, Albuquerque NM Citation: USDA Forest Service. 2018. Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest. Southwestern Region TP-R3-16-36, Albuquerque, NM. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339.