Fierce Species: Biological Imperialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum Pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, Or Independent Domestication

KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History ISSN: 0023-1940 (Print) 2051-6177 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ykiv20 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy To cite this article: Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy (2017): A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication, KIVA, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ykiv20 Download by: [184.99.134.102] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 06:14 kiva, 2017, 1–29 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham1, Karen R. Adams2, Susan J. Smith3, and Terence M. Murphy4 1 Department of Anthropology and Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB # 3115, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA, [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Archaeobotanical Consultant, 2837 E. Beverly Dr., Tucson, AZ 85716, USA 3 Consulting Archaeopalynologist, 8875 Carefree Ave., Flagstaff, AZ 86004, USA 4 Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Little Barley Grass (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) is a well-known native food do- mesticated in the U.S. -

Potential Distribution of the Invasive Old World Climbing Fern, Lygodium Microphyllum in North and South America

1 Running title: Potential distribution of invasive fern Potential distribution of the invasive Old World climbing fern, Lygodium microphyllum in North and South America John A. Goolsby, United States Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Australian Biological Control Laboratory, CSIRO Long Pocket Laboratories, 120 Meiers Rd. Indooroopilly, Queensland, Australia 4068 email: [email protected] 2100 words 2 Abstract: The climate matching program CLIMEX is used to predict the potential distribution of the fern, Lygodium microphyllum in North and South America, with particular reference to Florida, USA where it is invasive. A predictive model was fitted to express the known distribution of the fern. Several new collection locations were incorporated into the model based on surveys for the plant near its ecoclimatic limits in China and Australia. The model predicts that the climate is suitable for further expansion of L. microphyllum north into central Florida. Large parts of the Caribbean, Central and South America are also at risk. Index terms: Invasive species, weeds, Florida Everglades, predictive modeling, CLIMEX. INTRODUCTION Lygodium microphyllum (Cav.) R. Br. (Lygodiaceae, Pteridophyta), the Old World climbing fern, is native to the Old World wet tropics and subtropics of Africa, Asia, Australia, and Oceania (Pemberton 1998). It is an aggressive invasive weed in southern Florida, USA (Pemberton and Ferriter 1998) and is classified as a Category I invasive species by the Florida Exotic Plant Pest Council (Langeland and Craddock Burks 1998). It was first found to be naturalized in Florida 1965; however, its rapid spread is now a serious concern because of its dominance over native vegetation. -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

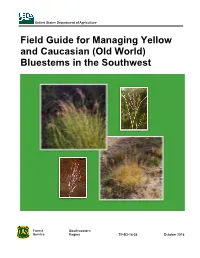

Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest

USDA United States Department of Agriculture - Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest Forest Southwestern Service Region TP-R3-16-36 October 2018 Cover Photos Top left — Yellow bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Top right — Yellow bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Billy Warrick; Soil, Crop and More Information Lower left — Caucasian bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Lower right — Caucasian bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Authors Karen R. Hickman — Professor, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater OK Keith Harmoney — Range Scientist, KSU Ag Research Center, Hays KS Allen White — Region 3 Pesticides/Invasive Species Coord., Forest Service, Albuquerque NM Citation: USDA Forest Service. 2018. Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest. Southwestern Region TP-R3-16-36, Albuquerque, NM. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

Voyage Calendar

February 2016 March 2016 April 2016 May 2016 June 2016 July 2016 August 2016 September 2016 October 2016 November 2016 December 2016 January 2017 February 2017 March 2017 April 2017 May 2017 June & July 2017 Alluring Andes & Majestic Fjords Journey Through the Amazon Mayan Mystique Northwest Wonders Coastal Alaska Coastal Alaska Coastal Alaska Accent on Autumn Beacons of Beauty Celebrate the Sunshine Pacific Holidays Baja & The Riviera Amazon Exploration Patagonian Odyssey Southern Flair The Great Northwest Lima to Buenos Aires Rio de Janeiro to Miami Miami to Miami San Francisco to Vancouver Seattle to Seattle Seattle to Seattle Seattle to Seattle New York to Montreal New York to Montreal Miami to Miami Miami to Los Angeles Los Angeles to Los Angeles Miami to Rio de Janeiro Buenos Aires to Lima Miami to Miami San Francisco to Vancouver 21 days | February 7 22 days | March 11 10 days | April 2 10 days | May 10 7 days | June 9 7 days | July 8 7 days | August 4 12 days | September 18 10 days | October 12 12 days | November 5 16 days | December 22 10 days | January 7 23 days | February 2 22 days | March 7 10 days | April 14 11 days | May 10 Radiant Rhythms Atlantic Charms Majesty of Alaska Glacial Explorer Majestic Beauty Glaciers & Gardens Fall Medley Landmarks & Lighthouses Caribbean Charisma Panama Enchantment Ancient Legends Palms in Paradise Buenos Aires to Rio de Janeiro Miami to Miami Vancouver to Seattle Seattle to Seattle Seattle to Seattle Seattle to Vancouver Montreal to New York Montreal to Miami Miami to Miami Los Angeles to -

ACTIVITY 20.1 Trading in the Old World–New World Market

THE COLUMBIAN EXCHANGE LESSON 20 ACTIVITY 20.1 Trading in the Old World–New World Market INTRODUCTION Voluntary trade usually makes both buyers and sellers better off. But trade is based on the benefi ts buyers and sellers expect to receive. Occasionally, people regret trades that they have made because their expectations were not realized. For example, people use the word “lemon” to describe an automobile that needs frequent repairs and does not perform as well as the buyer thought it would. If a buyer knew an automobile was a “lemon” she or he would not buy it, but people sometimes make trades with incomplete information. This is why voluntary exchange is defi ned as trading goods and services with other people because both parties expect to benefi t from the trade. This activity will teach students that some trades make people better off while other trades make people worse off because they have incomplete information. In this activity, students trade New World food cards and Old World food cards. Each of the New World food cards has a number in the lower the right-hand corner (1 though 16). The main ingredients of New World foods were available only in the New World, or Western Hemisphere, prior to the Columbian Exchange. Each of the Old World food cards has a letter (A through P) in the lower right-hand corner. The primary ingredients of Old World foods were available only in the Old World, or Eastern Hemisphere, prior to the Columbian Exchange. Recipes for some foods (for example, baby-back ribs and eggplant parmesan) have multiple ingredients, some of which may have originated in the New World or the Old World. -

Pest Alert: Old World Bollworm (Helicoverpa Armigera)

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Pest Alert Plant Protection and Quarantine Old World Bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) The Old World bollworm can feed on crops, such as corn, cotton, small grains, soybeans, peppers, and tomatoes. Damage occurs when the larvae bore into the host’s flowers and fruit and feed within the plant; the larvae may also feed on the leaves of host plants. This invasive pest can be found both in field and greenhouse settings. Distribution and Spread Old World bollworm is found in many areas of Africa, Asia, Europe, Australia, and the islands of the Western Pacific Region. It has also Old World bollworm adult (Julieta Brambila, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org) been reported in Brazil and may be present in other South and Central American countries. Old World bollworm was found on a single farm in Puerto Rico in September 2014. This was the first time the pest has been detected in the United States. Adults can fly up to 6 miles to find sufficient host material on which to Old World bollworm adult (Gyorgy Csoka, Hungary Old World bollworm larva (Antoine Guyonnet, Forest Research Institute, Bugwood.org) Lépidoptères Poitou-Charentes, Bugwood.org) lay eggs. They can be carried longer distances by wind. In Europe, for instance, the Old World bollworm in color and 0.6 to 0.9 inches long. Life Cycle migrates annually into Scandinavia Adults have a wingspan of 1.4 to from the Mediterranean. 1.6 inches and vary in color. Males Adults emerge from late March to are usually yellowish-brown, light June and lay eggs on a variety of Description yellow, or light brown, and females host plants. -

Old World Bluestem Pasture Management Strategies for Panhandle and South Plains1

Old World Bluestem Pasture Management Strategies for Panhandle and South Plains1 F.T. McCollum III, PAS-ACAN Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center Amarillo Origins and Varieties of Old World Bluestem Old World bluestems were introduced to the United States early in the 20th century. These introductions originated from eastern Europe and Asia - primarily Russia, Pakistan, India, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Turkey. Over 800 accessions are in a collection at the USDA-ARS Southern Plains Range Research Station in Woodward, OK. A number of these have been studied by the USDA-ARS at Woodward, Noble Foundation at Ardmore, OK, NRCS Plant Materials Centers, Oklahoma State University, Texas A&M University, and Texas Tech University. The following varieties are adapted to the Southern Plains region: Caucasian bluestem (Bothriochloa caucasica) - the first Old World bluestem used widely in the USA. A winter hardy variety that is adapted to a wide variety of soils as long as they are not calcareous or prone to erosion. In years with normal or above average rainfall, Caucasian is consistently the best forage producer among released varieties. Plains bluestem (Bothriochloa ischaemum) - a blend of 30 strains from six countries. The blend was intended to increase the probability of success in a variety of climatic and soil-site conditions and exposure to insect and disease pests. The better adapted strains will out compete the less adapted strains. So, the eventual composition of the stands can vary depending on the location and stressors at the site. This was possibly the most widely planted of the Old World bluestem releases. -

Mediterranean Legends Itinerary and Registration Form

Saint-Tropez Monte Carlo MEDITERRANEAN Florence Barcelona Livorno Valencia Palma de Rome LEGENDS Mallorca Sorrento/ Civitavecchia Capri 10-NIGHT LUXURY CRUISE ABOARD NAUTICA Messina MONTE CARLO TO BARCELONA Valletta OCTOBER 17–28, 2019 PLUS YOUR CHOICE OF 2-FOR-1 CRUISE FARES • 6 FREE SHORE EXCURSIONS FREE AIRFARE • OR FREE BEVERAGE PACKAGE FREE UNLIMITED INTERNET • OR $600 SHIPBOARD CREDIT ABOVE(ABOVE OFFERS OFFERS ARE AREPER PERSTATEROOM, PERSON) BASED ON DOUBLE OCCUPANCY STATEROOM ITINERARY CATEGORIES Day 1 Depart for Monaco Inside Stateroom Day 2 Monte Carlo, Monaco G $2,699 Day 3 Saint-Tropez, France F $2,899 Day 4 Florence/Pisa/Tuscany (Livorno), Italy Ocean View E $3,049 Day 5 Rome (Civitavecchia), Italy WHY TRAVELERS PREFER D $3,199 Day 6 Sorrento/Capri, Italy AND NAUTICA Deluxe Ocean View Day 7 Messina, Sicily, Italy The Ambience C2 $3,399 • Luxurious yet relaxed atmosphere Day 8 Valletta, Malta C1 $3,499 • Intimate 684–guest ship, providing access to more exotic ports Day 9 At Sea Veranda • Exceptional decor with museum-quality art Day 10 Palma de Mallorca, Spain B2 $4,099 • Resort casual attire—no formal nights Day 11 Valencia, Spain B1 $4,249 The Distinction Day 12 Barcelona, Spain Concierge Veranda • Impressive staff-to-guest ratio: 1 to 1.7 A3 • Award-winning Canyon Ranch SpaClub® and fitness center $4,449 • Enrichment programs including seminars led by naturalists, A2 $4,549 historians, and local experts A1 $4,699 The Flavor Penthouse Suite • The Finest Cuisine at Sea™, under the culinary direction of PH3 $5,499 renowned -

Free PDF Download

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTHWEST CONTINUE ON TO THE NEXT PAGE FOR YOUR magazineFREE PDF (formerly the Center for Desert Archaeology) is a private 501 (c) (3) nonprofit organization that explores and protects the places of our past across the American Southwest and Mexican Northwest. We have developed an integrated, conservation- based approach known as Preservation Archaeology. Although Preservation Archaeology begins with the active protection of archaeological sites, it doesn’t end there. We utilize holistic, low-impact investigation methods in order to pursue big-picture questions about what life was like long ago. As a part of our mission to help foster advocacy and appreciation for the special places of our past, we share our discoveries with the public. This free back issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine is one of many ways we connect people with the Southwest’s rich past. Enjoy! Not yet a member? Join today! Membership to Archaeology Southwest includes: » A Subscription to our esteemed, quarterly Archaeology Southwest Magazine » Updates from This Month at Archaeology Southwest, our monthly e-newsletter » 25% off purchases of in-print, in-stock publications through our bookstore » Discounted registration fees for Hands-On Archaeology classes and workshops » Free pdf downloads of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, including our current and most recent issues » Access to our on-site research library » Invitations to our annual members’ meeting, as well as other special events and lectures Join us at archaeologysouthwest.org/how-to-help In the meantime, stay informed at our regularly updated Facebook page! 300 N Ash Alley, Tucson AZ, 85701 • (520) 882-6946 • [email protected] • www.archaeologysouthwest.org ™ Archaeology Southwest Volume 23, Number 1 Center for Desert Archaeology Winter 2009 The Latest Research on the Earliest Farmers Sarah A. -

Synchrony in the New World: an Example of Archaeoethnology

10.1177/1069397105282507Cross-CulturalPeregrine / SYNCHRONY Research / FebruaryIN THE NEW 2006 WORLD Synchrony in the New World: An Example of Archaeoethnology Peter N. Peregrine Lawrence University Christopher Chase-Dunn and colleagues have demonstrated cycles of synchronous growth and decline in cities in East Asia and in the Mediterranean. They argue that synchrony is rooted in systems of economic and political interdependence, cutting across broad re- gions of the world for long periods of history. Using a new strategy for cross-cultural research in the anthropological sciences— archaeoethnology, the cross-cultural analysis of archaeological cultures in a diachronic mode—the author examines whether set- tlement synchrony has occurred in the New World and if so, whether it implies widespread economic and political interdepen- dencies across long periods of time. Keywords: archaeology; New World prehistory; cultural evolu- tion; time-series analysis Christopher Chase-Dunn and colleagues have recently demon- strated an interesting pattern of urban dynamics in Europe, North Africa, and Asia during the past 4,000 years (e.g., Chase-Dunn & Hall, 1997; Chase-Dunn & Willard, 1993). They show, using the geographical area and estimated population of cities known from historical and archaeological contexts, that changes in city size in Cross-Cultural Research, Vol. 40 No. 1, February 2006 1-12 DOI: 10.1177/1069397105282507 © 2006 Sage Publications 1 2 Cross-Cultural Research / February 2006 one part of this broad region anticipate and perhaps cause change in other parts of the region (Chase-Dunn, Manning, & Hall, 2000). Chase-Dunn and colleagues term this pattern “city synchronicity” and demonstrate long-term patterns of synchrony across large re- gions of the Old World (Chase-Dunn & Manning, 2002). -

New Eyes on the Old World GIS Helps Us Understand the Past While Preparing for the Future Table of Contents

July 2013 New Eyes on the Old World GIS Helps Us Understand the Past While Preparing for the Future Table of Contents 3 Introduction 4 What Is GIS? 5 GIS and Ancient Trees Reveal Past Temperatures and Climate Change 10 Cultural Heritage Management and GIS in Petra, Jordan 16 CityEngine Creates New Solutions for Historic Cities 21 The Greek Island of Kythera Jumps to the Forefront of Historical Research 25 A New Probe for CSI? 29 Predicting Prehistoric Site Location in the Southern Caucasus 32 Photogrammetric Modeling + GIS 39 Temporally Discrete Prehistoric Activity Identified New Eyes on the Old World 2 Introduction Archaeologists, historians, and cultural resource managers understand the importance of geography. Its variables exert a strong influence on human behavior today, just as it did in the past. Geography also influences the degree to which archaeological and historical sites are exposed to and impacted by human activity and natural forces. GIS facilitates mapping to analyze depositional patterns, catalog and quantify cultural resources, and provide a well-structured descriptive and analytical tool for identifying spatial patterns. It is also an invaluable tool for protecting and stewarding cultural resources into the future. New Eyes on the Old World Introduction 3 What Is GIS? Making decisions based on geography is basic to human thinking. countries have an abundance of geographic data for analysis, and Where shall we go, what will it be like, and what shall we do when governments often make GIS datasets publicly available. Map we get there are applied to the simple event of going to the store file databases often come included with GIS packages; others or to the major event of launching a bathysphere into the ocean’s can be obtained from both commercial vendors and government depths.