Free PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IOM Regional Strategy 2020-2024 South America

SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Av. Santa Fe 1460, 5th floor C1060ABN Buenos Aires Argentina Tel.: +54 11 4813 3330 Email: [email protected] Website: https://robuenosaires.iom.int/ Cover photo: A Syrian family – beneficiaries of the “Syria Programme” – is welcomed by IOM staff at the Ezeiza International Airport in Buenos Aires. © IOM 2018 _____________________________________________ ISBN 978-92-9068-886-0 (PDF) © 2020 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. PUB2020/054/EL SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 FOREWORD In November 2019, the IOM Strategic Vision was presented to Member States. It reflects the Organization’s view of how it will need to develop over a five-year period, in order to effectively address complex challenges and seize the many opportunities migration offers to both migrants and society. It responds to new and emerging responsibilities – including membership in the United Nations and coordination of the United Nations Network on Migration – as we enter the Decade of Action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. -

A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum Pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, Or Independent Domestication

KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History ISSN: 0023-1940 (Print) 2051-6177 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ykiv20 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy To cite this article: Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy (2017): A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication, KIVA, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ykiv20 Download by: [184.99.134.102] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 06:14 kiva, 2017, 1–29 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham1, Karen R. Adams2, Susan J. Smith3, and Terence M. Murphy4 1 Department of Anthropology and Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB # 3115, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA, [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Archaeobotanical Consultant, 2837 E. Beverly Dr., Tucson, AZ 85716, USA 3 Consulting Archaeopalynologist, 8875 Carefree Ave., Flagstaff, AZ 86004, USA 4 Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Little Barley Grass (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) is a well-known native food do- mesticated in the U.S. -

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

KNOTLESS NETTING in AMERICA and OCEANIA T HE Question Of

116 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST [N. s., 37, 1935 48. tcdbada'b stepson, stepdaughter, son or KNOTLESS NETTING IN AMERICA daughter of wife's brother or sis AND OCEANIA By D. S. DAVIDSON ter, son or daughter of husband's brother or sister: reciprocal to the HE question of trans-Pacific influences in American cultureshas been two preceding terms 49. tcdtsa'pa..:B T seriously debated for a number of years. Those who favor a trans step~grandfather, husband of oceanic movement have pointed out many resemblances and several grandparent's'sister 50. tCLlka 'yaBB striking similarities between certain culture traits of the New World and step-grandmother, wife of grand Oceania. The theory of a historical relationship between these appearances parent's brother 51. tcde'batsal' is based upon the hypothesis that independent invention and convergence step-grandchild, grandchild of speaker's wife's (or speaker's hus in development are not reasonable explanations either for the great number band's) brother or sister: recipro of resemblances or for the certain complexities found in the two areas. c~l to the two preceding terms The well-known objections to the trans-Pacific diffusion theory can 52. tsi.J.we'bats husband Or wife of grandchild of be summarized as follows: speaker or speaker's brother or 1. That many of the so-called similarities at best are only resemblances sister; term possibly reciprocal between very simple traits which might be independently invented or 53. tctlsxa'xaBll son-in-law or daughter-in-law of discovered. speaker's wife's brother or sister, 2. -

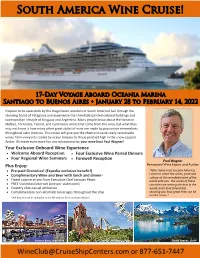

South America Wine Cruise!

South America Wine Cruise! 17-Day Voyage Aboard Oceania Marina Santiago to Buenos Aires January 28 to February 14, 2022 Prepare to be awestruck by the magnificent wonders of South America! Sail through the stunning fjords of Patagonia and experience the cheerfully painted colonial buildings and cosmopolitan lifestyle of Uruguay and Argentina. Many people know about the fantastic Malbec, Torrontes, Tannat, and Carminiere wines that come from this area, but what they may not know is how many other great styles of wine are made by passionate winemakers throughout Latin America. This cruise will give you the chance to taste really remarkable wines from vineyards cooled by ocean breezes to those perched high in the snow-capped Andes. All made even more fun and educational by your wine host Paul Wagner! Your Exclusive Onboard Wine Experience Welcome Aboard Reception Four Exclusive Wine Paired Dinners Four Regional Wine Seminars Farewell Reception Paul Wagner Plus Enjoy: Renowned Wine Expert and Author Pre-paid Gratuities! (Expedia exclusive benefit!) "After many trips to Latin America, I want to share the wines, food and Complimentary Wine and Beer with lunch and dinner* culture of this wonderful part of the Finest cuisine at sea from Executive Chef Jacques Pépin world with you. The wines of these FREE Unlimited Internet (one per stateroom) countries are among the best in the Country club-casual ambiance world, and I look forward to Complimentary non-alcoholic beverages throughout the ship showing you how great they can be on this cruise.” *Ask how this can be upgraded to the All Inclusive Drink package onboard. -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

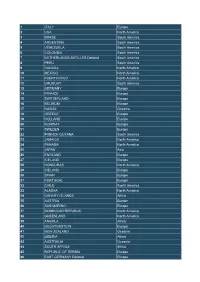

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information

Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information Updated August 5, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46225 SUMMARY R46225 Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical August 5, 2021 Information Carla Y. Davis-Castro This report provides statistical information on Indigenous peoples in Latin America. Data and Research Librarian findings vary, sometimes greatly, on all topics covered in this report, including populations and languages, socioeconomic data, land and natural resources, human rights and international legal conventions. For example the figure below shows four estimates for the Indigenous population of Latin America ranging from 41.8 million to 53.4 million. The statistics vary depending on the source methodology, changes in national censuses, the number of countries covered, and the years examined. Indigenous Population and Percentage of General Population of Latin America Sources: Graphic created by CRS using the World Bank’s LAC Equity Lab with webpage last updated in July 2021; ECLAC and FILAC’s 2020 Los pueblos indígenas de América Latina - Abya Yala y la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible: tensiones y desafíos desde una perspectiva territorial; the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank’s (WB) 2015 Indigenous Latin America in the twenty-first century: the first decade; and ECLAC’s 2014 Guaranteeing Indigenous people’s rights in Latin America: Progress in the past decade and remaining challenges. Notes: The World Bank’s LAC Equity Lab -

Asia's Rise in the New World Trade Order

GED Study Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order The Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements on Asian Countries Part 2 of the GED Study Series: Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements Authors Dr. Cora Jungbluth (Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh), Dr. Rahel Aichele (ifo, München), Prof. Gabriel Felbermayr, PhD (ifo and LMU, München) GED Study Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order The Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements on Asian Countries Part 2 of the GED Study Series: Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order Table of contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction: Mega-regionals and the new world trade order 6 2. Asia in world trade: A look at the “noodle bowl” 10 3. Mega-regionals in the Asia-Pacific region and their effects on Asian countries 14 3.1 The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): The United States’ “pivot to Asia” in trade 14 3.2 The Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP): An inclusive alternative? 16 3.3 The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP): The ASEAN initiative 18 4. Case studies 20 4.1 China: The world’s leading trading nation need not fear the TPP 20 4.2 Malaysia: The “Asian Tiger Cub” profits from deeper transpacific integration 22 5. Parallel scenarios: Asian-Pacific trade deals as counterweight to the TTIP 25 6. Conclusion: Asia as the driver for trade integration in the 21st century 28 Appendix 30 Bibliography 30 List of abbreviations 34 List of figures 35 List of tables 35 List of the 20 Asian countries included in our analysis 36 Links to the fact sheets of the 20 Asian countries included in our analysis 37 About the authors 39 Imprint 39 4 Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order Executive summary Asia is one of the most dynamic regions in the world and the FTAAP, according to our calculations the RCEP also has the potential to become the key region in world trade has positive economic effects for most countries in Asia, in the 21st century. -

Two Centuries of International Migration

IZA DP No. 7866 Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Timothy J. Hatton December 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Northwestern University Timothy J. Hatton University of Essex, Australian National University and IZA Discussion Paper No. 7866 December 2013 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

Mummies and Mummification Practices in the Southern and Southwestern United States Mahmoud Y

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 1998 Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States Mahmoud Y. El-Najjar Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan Thomas M. J. Mulinski Chicago, Illinois Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard El-Najjar, Mahmoud Y.; Mulinski, Thomas M. J.; and Reinhard, Karl, "Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States" (1998). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in MUMMIES, DISEASE & ANCIENT CULTURES, Second Edition, ed. Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn, and Theodore A. Reyman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 7 pp. 121–137. Copyright © 1998 Cambridge University Press. Used by permission. Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States MAHMOUD Y. EL-NAJJAR, THOMAS M.J. MULINSKI AND KARL J. REINHARD Mummification was not intentional for most North American prehistoric cultures. Natural mummification occurred in the dry areas ofNorth America, where mummies have been recovered from rock shelters, caves, and over hangs. In these places, corpses desiccated and spontaneously mummified. In North America, mummies are recovered from four main regions: the south ern and southwestern United States, the Aleutian Islands, and the Ozark Mountains ofArkansas. -

Conerence Entitled "Understanding Population Change: *United States

AUTHOR Roseman-, Curti And Others TITLE Population Redistribution in the Mi wes INSTITUTION North 'central Regional Center for Ru al Development Ames,. Iowa. 1PONS -AGENgY --Department-of Agriculture, WashingtoA C. PUB DATE Nay 81 . NOTE 22BR.: 'Papers were ofiginally presented at a conerence entitled "Understanding Population Change: Issuei and Consequences of Population Redistribution ' in the Midwest" (Champaign, IL, Birch 12, 1979). EDPS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Decentraliiation: *Demography: Employment Patterns: Geography: Indubtry: Land Use: Migrants: *Migration' Patterns: Politics: *Population Distribution: Public Policy: Research Needs: *Rural Ardasi *Urban to Rural Migtation IDENTIFI *United States (Midwest ABSTRACT The-ninechapter0-in the book f4dus on the 1970s' metropolitan to-4nOnmetropolitan migration stream and address both population -patterns and`'-prooesses and the impacts and policy issues associated with the result-in-q, popUlation'redistribution in the Midwest. Peter A. Morrison places the Midwest in the national context of changing population structure and redistribution. John R Borchert traces the,Ilistorical and geographic forCeS which have shaped the 'current'patterts.:CalvinL.. Bealeand Glenn V. Fuguittfocus. on deiographicaspedtt Mf,redistribution'in.W Midwest. Ralph R. 'lifter' and Richard W. Buxbaum place Midwest trends in a policy context. Andrew J. Sofranko, James D. Williams, and prederick C. Fliegel disduss. a survey offecent migrantS to fastzgrowing Midwest' nonmetropolitan areas. RiehardLonsdale documents the decentralization trend in manufacturing employment and. its role, in population redistribution. David Bdtry-examinesthe:significance-of land cOnverSton:from rural to 'urban uses. Alvin D. Sokolov addresses - the localpolitical implications\of recent small town growth. ,Laurence S. ROsen.outlines and analyzes methods and data needed for population pitolectiOns.-- fAuthOt,SEI --_*****#****** ********.