Frequency Compensation of an Audio Power Amplifier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indirect Compensation Techniques for Three- Stage Fully-Differential Op-Amps

1 Indirect Compensation Techniques for Three- Stage Fully-Differential Op-amps Vishal Saxena, Student Member, IEEE and R. Jacob Baker, Senior Member, IEEE op-amps. A novel cascaded fully-differential, three-stage op- Abstract— As CMOS technology continues to evolve, the amp topology is presented with simulation results, which is supply voltages are decreasing while at the same time the tolerant to device mismatches and exhibits superior transistor threshold voltages are remaining relatively constant. performance. Making matters worse, the inherent gain available from the nano-CMOS transistors is dropping. Traditional techniques for achieving high-gain by cascoding become less useful in nano-scale II. INDIRECT FEEDBACK COMPENSATION CMOS processes. Horizontal cascading (multi-stage) must be Indirect Feedback Compensation is a lucrative method to used in order to realize high-gain op-amps in low supply voltage compensate op-amps for higher speed operation [1]. In this processes. This paper discusses indirect compensation techniques for op-amps using split-length devices. A reversed-nested indirect method, the compensation capacitor is connected to an internal compensated (RNIC) topology, employing double pole-zero low impedance node in the first gain stage, which allows cancellation, is illustrated for the design of three-stage op-amps. indirect feedback of the compensation current from the output The RNIC topology is then extended to the design of three-stage node to the internal high-impedance node. Further, in nano- fully-differential op-amps. Novel three-stage fully-differential CMOS processes low-voltage, high-speed op-amps can be gain-stage cascade structures are presented with efficient designed by employing a split-length composite transistor for common mode feedback (CMFB) stabilization. -

Switch-Mode Power Converter Compensation Made Easy

Switch-mode power converter compensation made easy Robert Sheehan Systems Manager, Power Design Services Member Group Technical Staff Louis Diana Field Application, America Sales and Marketing Senior Member Technical Staff Texas Instruments Using this paper as a quick look-up reference can help designers compensate the most popular switch-mode power converter topologies. Engineers have been designing switch-mode power converters for some time now. If you’re new to the design field or you don’t compensate converters all the time, compensation requires some research to do correctly. This paper will break the procedure down into a step-by-step process that you can follow to compensate a power converter. We will explain the theory of compensation and why it is necessary, examine various power stages, and show how to determine where to place the poles and zeros of the compensation network to compensate a power converter. We will examine typical error amplifiers as well as transconductance amplifiers to see how each affects the control loop and work through a number of topologies/examples so that power engineers have a quick reference when they need to compensate a power converter. Introduction Many SMPS designers would appreciate a how- A switch-mode power supply (SMPS) regulates to reference paper that they can use to look up the output voltage against any changes in compensation solutions to various topologies with output loading or input line voltage. An SMPS various feedback modes. We are striving to provide accomplishes this regulation with a feedback loop, this in a single paper. which requires compensation if it has an error Control-loop and compensation amplifier with linear feedback. -

Differential AC Boosting Compensation for Power-Efficient

Copyright © 2019 American Scientific Publishers Journal of All rights reserved Low Power Electronics Printed in the United States of America Vol. 15, 379–387, 2019 Differential AC Boosting Compensation for Power-Efficient Multistage Amplifiers Tayebeh Asiyabi1 and Jafar Torfifard2 ∗ 1Department of Electrical Engineering, Mahshahr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Mahshahr, Iran 2Department of Electrical Engineering, Izeh Branch, Islamic Azad University, Izeh, Iran (Received: 26 February 2019; Accepted: 22 July 2019) In this paper, a new architecture of four-stage CMOS operational transconductance amplifier (OTA) based on an alternative differential AC boosting compensation called DACBC is proposed. The pre- sented structure removes feedforward and boosts feedback paths of compensation network simul- taneously. Moreover, the presented circuit uses a fairly small compensation capacitor in the order of 1 pF, which makes the circuit very compact regarding enhanced several small-signal and large- signal characteristics. The proposed circuit along with several state-of-the-art schemes from the literature have been extensively analysed and compared together. The simulation results show with the same capacitive load and power dissipation the unity-gain frequency (UGF) can be improved over 60 times than conventional nested Miller compensation. The results of the presented OTA with 15 pF capacitive load demonstrated 65 phase margin, 18.88 MHz as UGF and DC gain of 115 dB with power dissipation of 462 Wfrom1.8V. Keywords: Differential AC Boosting, Frequency Compensation, CMOS Operational IP: 192.168.39.210 On: Sun, 03 Oct 2021 15:57:22 TransconductanceCopyright: Amplifier American (OTA), Scientific Low Power, Publishers Low Voltage. Delivered by Ingenta 1. INTRODUCTION is compulsory for high-precision purposes. -

Design and Implementation of a Signal Conditioning Operational Amplifier for a Reflective Object Sensor

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2010 Design and Implementation of a Signal Conditioning Operational Amplifier for a Reflective Object Sensor Ankit Master University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Electrical and Electronics Commons, and the VLSI and Circuits, Embedded and Hardware Systems Commons Recommended Citation Master, Ankit, "Design and Implementation of a Signal Conditioning Operational Amplifier for a Reflective Object Sensor. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/820 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Ankit Master entitled "Design and Implementation of a Signal Conditioning Operational Amplifier for a Reflective Object Sensor." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Electrical Engineering. Benjamin J. Blalock, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: -

AN-1604 Decompensated Operational Amplifiers

Application Report SNOA486B–March 2007–Revised May 2013 AN-1604 Decompensated Operational Amplifiers ..................................................................................................................................................... ABSTRACT This application report discusses the what, why, and where of decompensated op amps. This application report also describes external compensation techniques, such as reducing loop gain, to stabilize op amps operated at gains less than the minimum stable gain specified in the datasheet. A comprehensive treatment of input lead-lag compensation including examples is presented. Contents 1 Introduction to Decompensated Amplifiers .............................................................................. 2 2 Using External Compensation to Stabilize Decompensated Gains Below the Minimum Specified .............. 3 3 Input Lead-Lag Compensation ............................................................................................ 8 4 Input Lead-Lag Compensation for Inverting Configurations ......................................................... 11 5 Input Lead-Lag Compensation for Non-Inverting Configurations ................................................... 13 6 Summary of Input Lead-Lag Compensation ........................................................................... 14 List of Figures 1 Gain vs. Frequency Characteristics for a Unity Gain Stable Op Amp and a Decompensated Op Amp......... 2 2 Three-Terminal Network Circuit .......................................................................................... -

Design Trade-Offs in Common-Mode Feedback Implementations for Highly Linear Three-Stage Operational Transconductance Amplifiers

electronics Article Design Trade-Offs in Common-Mode Feedback Implementations for Highly Linear Three-Stage Operational Transconductance Amplifiers Joseph Riad 1,* , Sergio Soto-Aguilar 1 , Johan J. Estrada-López 2,* , Oscar Moreira-Tamayo 1 and Edgar Sánchez-Sinencio 1 1 Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA; [email protected] (S.S.-A.); [email protected] (O.M.-T.); [email protected] (E.S.-S.) 2 Faculty of Mathematics, Autonomous University of Yucatán, Mérida 97110, Yucatán, Mexico * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.R.); [email protected] (J.J.E.-L.) Abstract: Fully differential amplifiers require the use of common-mode feedback (CMFB) circuits to properly set the amplifier’s operating point. Due to scaling trends in CMOS technology, modern amplifiers increasingly rely on cascading more than two stages to achieve sufficient gain. With multiple gain stages, different topologies for implementing CMFB are possible, whether using a single CMFB loop or multiple ones. However, the impact on performance of each CMFB approach has seldom been studied in the literature. The aim of this work is to guide the choice of the CMFB implementation topology evaluating performance in terms of stability, linearity, noise and common- mode rejection. We present a detailed theoretical analysis, comparing the relative performance of Citation: Riad, J.; Soto-Aguilar, S.; two CMFB configurations for 3-stage OTA topologies in an implementation-agnostic manner. Our Estrada-López, J.J.; Moreira-Tamayo, analysis is then corroborated through a case study with full simulation results comparing the two O.; Sánchez-Sinencio, E. -

Double-Pole Compensation and the Push-Pull Transimpedance Stage in Discrete Audio Frequency Power Amplifiers

DOUBLE-POLE COMPENSATION AND THE PUSH-PULL TRANSIMPEDANCE STAGE IN DISCRETE AUDIO FREQUENCY POWER AMPLIFIERS Michael Kiwanuka, B.Sc. (Hons) Electronic Engineering Everything should be made as simple as possible—but no simpler! ~ Albert Einstein Introduction Sometime ago a fascinating debate ensued ,,, 4321 in respect of improvements that might be made to the venerable double cascaded differential stages (DCDS) gain block recommended by Hitachi 5 for use with their power MOSFETs. Alas, there was much missing of the point, as the suggested modifications did not accommodate the essential linearity-enhancing techniques detailed by Douglas Self in his seminal work ,, 876 . It is demonstrated here that such a topology need not compromise on linearity; however, the increase in complexity and cost may be relatively significant. The transient and steady state conduct of an amplifier is inextricably linked to the choice of frequency stabilisation. Prominence is therefore given to a first-order analysis of double-pole compensation as a desirable and cost-effective means of reducing forward-path error. A brief overview of loop transmission and its determination in context is also provided. A first-principals approach is preferred and adhered to whenever appropriate. The Classical Topology The circuit of figure 1 is, with some modification, broadly similar to Self’s adaptation, for medium power discrete-component audio power amplification, of the two-stage voltage gain topology attributed to J. E. Thompson by Messrs Russell and Solomon 9 . Incidentally, this circuit is sometimes inexplicably and somewhat tendentiously classified 10 as the “Lin” topology after the inventor 11 of the single gain stage quasi-complementary design shown in its entirety in figure 2 . -

AN142 Audio Circuits Using the NE5532/3/4 Author 1984 Oct

INTEGRATED CIRCUITS AN142 Audio circuits using the NE5532/3/4 author 1984 Oct Philips Semiconductors Philips Semiconductors Application note Audio circuits using the NE5532/3/4 AN142 AUDIO CIRCUITS USING THE NE5532/33/34 actually five individual active filters with the same feedback design The following will explain some of Philips Semiconductors low noise for all five. The main difference in all five stages is the values of C5 op amps and show their use in some audio applications. and C6, which are responsible for setting the center frequency of each stage. Linear pots are recommended for R9. To simplify use of this circuit, a component value table is provided, which lists center DESCRIPTION frequencies and their associated capacitor values. Notice that C5 The 5532 is a dual high-performance low noise operational amplifier. equals (10) C6, and that the Value of R8 and R10 are related to R9 Compared to most of the standard operational amplifiers, such as by a factor of 10 as well. The values listed in the table are common the 1458, it shows better noise performance, improved output drive and easily found standard values. capability and considerably higher small-signal and power bandwidths. RIAA EQUALIZATION AUDIO PREAMPLIFIER This makes the device especially suitable for application in high USING NE5532A quality and professional audio equipment, instrumentation and With the onset of new recording techniques with sophisticated control circuits, and telephone channel amplifiers. The op amp is playback equipment, a new breed of low noise operational amplifiers internally-compensated for gains equal to one. If very low noise is of was developed to complement the state-of-the-art in audio prime importance, it is recommended that the 5532A version be reproduction. -

The TL431 in Loop Control

The TL431 in Switch-Mode Power Supplies loops: part I Christophe Basso, Petr Kadanka − ON Semiconductor 14, rue Paul Mesplé – BP53512 - 31035 TOULOUSE Cedex 1 - France The technicall literature on loop control abounds with design examples of compensators implementing an operational amplifier (op amp). If the op amp certainly represents a possible way to generate an error signal, the industry choice for this function has been different for many years: almost all consumer power supplies involve a TL431 placed on the isolated secondary side to feed the error back to the primary side via an opto coupler. Despite its similarities with its op amp cousin, the design of a compensator around a TL431 requires a good understanding of the device operation. This first part explores the internal structure of the device and details how its biasing conditions can degrade the performance of the loop. A band-gap-based component Figure 1 shows the internal schematic of a TL431 made in a bipolar technology. Before we detail the usage of the component itself in a power supply loop, we believe it is important to understand how the device operates. The bias points are coming from a simple simulation setup where the device was used as a reference voltage. This configuration implies a connection between it reference point, ref , and the cathode k, while the anode a is grounded, making the device behave as an active 2.5-V zener diode. k R7 R8 760 760 7.01V 7.01V 12 13 7.07V Q8 Q9 C2 ref 2N3906 2N3906 8p Q2 2.49V 2N3904 Q3 2N3904 1.87V 4 I I 6.46V 1 1 14 Q10 1.24V 2 2N3904 Q7 2N3904 637mV 16 1.29V R9 10 R1 I 240 2k 1 R6 1.12V 4K 17 3 D1 970mV R2 BV = 36V R3 11 584mV Q11 C1 N = 1.3 1.9k 5.7k 2N3904 20p D2 585mV 581mV Q6 1N4148 5 6 2N3904 3I 1 I1 R5 R10 Q4 4k Q1 6.6k 2N3904 580mV9 2N3904 Area = 3 Q5 45.9mV 2N3904 7 Area = 6 I I R4 1 1 482 a Figure 1 : the internal schematic of a typical TL431 from ON Semiconductor where bias points in voltage and current have been captured at the equilibrium. -

Indirect Feedback Compensation Techniques for Multi-Stage

INDIRECT FEEDBACK COMPENSATION TECHNIQUES FOR MULTI-STAGE OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIERS by Vishal Saxena A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Electrical Engineering Boise State University October 2007 © 2007 Vishal Saxena ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The thesis presented by Vishal Saxena entitled “Indirect Feedback Compensation Tech- niques for Multi-Stage Operational Amplifiers” is hereby approved: __________________________________________ R. Jacob Baker Date Advisor __________________________________________ Kris Campbell Date Committee Member __________________________________________ John Chiasson Date Committee Member __________________________________________ John R. (Jack) Pelton Date Dean of the Graduate College DEDICATION This work is dedicated to Shri Narayana - the eternal witness beyond the manifest, Shri Sharada - the knowledge personified, and to the timeless masters of the Advaita Vedanta (Non-dualistic Idealism) philosophy. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like thank my advisor Dr. Jake Baker for teaching a series of wonderful courses on Analog and Mixed Signal Circuit Design and for encouraging me to engage in creative research through his continued support and fraternal guidance. His alacritous responses to my ideas have been of invaluable help to me in obtaining significant advances in circuit design. I have learned immensely from his diligent work ethics, his phenomenal teaching and his strikingly humane approach. I would also like to thank my teachers and colleagues at Indian Institute of Technology Madras for instilling an attitude of academic excellence in me. Further, I would like to thank Dr. Jeff Jessing, Dr. Stephen Parke and Dr. John Chiasson for teaching valuable courses at BSU and Dr. Kris Campbell for being on my thesis committee. Immense thanks to my parents, siblings Divya and Akshay for their unfettered affection and support. -

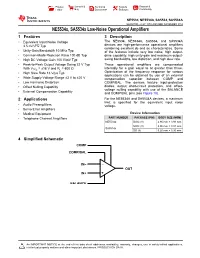

Ne5534x, Sa5534x Low-Noise Operational Amplifiers Datasheet (Rev. D)

Product Sample & Technical Tools & Support & Folder Buy Documents Software Community NE5534, NE5534A, SA5534, SA5534A SLOS070D –JULY 1979–REVISED NOVEMBER 2014 NE5534x, SA5534x Low-Noise Operational Amplifiers 1 Features 3 Description The NE5534, NE5534A, SA5534, and SA5534A 1• Equivalent Input Noise Voltage 3.5 nV/√Hz Typ devices are high-performance operational amplifiers combining excellent dc and ac characteristics. Some • Unity-Gain Bandwidth 10 MHz Typ of the features include very low noise, high output- • Common-Mode Rejection Ratio 100 dB Typ drive capability, high unity-gain and maximum-output- • High DC Voltage Gain 100 V/mV Typ swing bandwidths, low distortion, and high slew rate. • Peak-to-Peak Output Voltage Swing 32 V Typ These operational amplifiers are compensated With VCC± = ±18 V and RL = 600 Ω internally for a gain equal to or greater than three. • High Slew Rate 13 V/μs Typ Optimization of the frequency response for various applications can be obtained by use of an external • Wide Supply-Voltage Range ±3 V to ±20 V compensation capacitor between COMP and • Low Harmonic Distortion COMP/BAL. The devices feature input-protection • Offset Nulling Capability diodes, output short-circuit protection, and offset- voltage nulling capability with use of the BALANCE • External Compensation Capability and COMP/BAL pins (see Figure 10). 2 Applications For the NE5534A and SA5534A devices, a maximum limit is specified for the equivalent input noise • Audio Preamplifiers voltage. • Servo Error Amplifiers • Medical Equipment Device Information • Telephone Channel Amplifiers PART NUMBER PACKAGE (PIN) BODY SIZE (NOM) NE5534x SOIC (8) 4.90 mm × 3.91 mm SOIC (8) 4.90 mm × 3.91 mm SA5534x SO (8) 6.20 mm × 5.30 mm 4 Simplified Schematic COMP COMP/BAL IN− − OUT IN+ + BALANCE 1 An IMPORTANT NOTICE at the end of this data sheet addresses availability, warranty, changes, use in safety-critical applications, intellectual property matters and other important disclaimers. -

Frequency Compensation of an Operational Amplifier (Computer Experiment)

Frequency Compensation of an Operational Amplifier (Computer Experiment) ECE 3200 Electronics II updated 6 April 2020 References 1. A. S. Sedra and K. C. Smith, Microelectronic Circuits, 6th ed., Oxford University Press, 2009. Objectives 1. To develop an in-depth understanding of frequency compensation and negative feedback 2. To apply mathematical and/or circuit analysis skills and software to a non-trivial engineering design problem Procedures (MUST BE COMPLETED INDIVIDUALLY) 1. Document all work for this lab in your laboratory notebook. When performing this lab you may use any suitable mathematical and/or circuit analysis tools, e.g. LTspice (linear.com), MATLAB®, etc. 2. Op-Amp Characterization. Figure 1 shows the model of an operational amplifier to be used in this experiment. Find the transfer function ( ) = ( )/ ( ). Provide a Bode magnitude and phase plot for this transfer function. 3. Uncompensated Closed Loop Operation. Now consider use of the operational amplifier of Figure 1 in the non-inverting amplifier configuration of Figure 2. Assume = 0. Find the minimum closed loop gain that will guarantee stable amplifier operation. While your Bode plot can be used to obtain an approximate gain, your final answer must be within 0.5% of the true value. Thus you will need to use computational and not graphical techniques to obtain the gain value. 4. Consider use of the non-inverting amplifier configuration of Figure 2 to obtain a closed loop gain of 60dB. Based on your previous results, will this circuit “work?” Plot the time domain response ( ) of this circuit to a 1mV step input. 5. Compensation . Determine all component values (including the value of ) so that the operational amplifier of Figure 1 can be used to provide a closed loop gain of 60dB with a phase margin of 45° ± 1% using the non-inverting configuration of Figure 2.