Exhibition Handout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

Robert Frank Memories 12/09/2020 — 10/01/2021

Robert Frank Memories 12/09/2020 — 10/01/2021 Robert Frank, who was born in Zurich in 1924 and died last year in Canada, is widely regarded as one of the most important photographers of our time. Over the course of decades, he has expanded the boundaries of photography and explored its narrative potential like no other. Robert Frank travelled thousands of miles between the American East and West Coasts in the mid-1950s, going through nearly 700 films in the process. A selection of 83 black-and-white images from this blend of diary, sombre social portrait and photographic road movie would leave its mark on generations of photographers to come. The photobook The Americans was first published in Paris, followed by the US in 1959 – with an introduction by Beat writer Jack Kerouac, no less. Off-kilter compositions, cut-off figures and blurred motion marked a new photographic style teetering between documentation and narration that would have a profound impact on postwar photography. It is quite possibly the single most influential book in the history of photography; however, rather than being a spontaneous stroke of genius, Frank had worked on his subjective visual language for years. Many of his photographs from Switzerland, Europe and South America, as well as his rarely shown works from the USA in the early 1950s, are on a par with the famous classics from The Americans. The photographer’s early work, which remained unpublished for editorial reasons and is therefore little known to this day, reveals connections to those iconic pictures that still define our image of America, even today. -

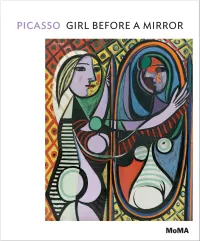

Picasso: Girl Before a Mirror

PICASSO GIRL BEFORE A MIRROR ANNE UMLAND THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK At some point on Wednesday, March 14, 1932, Pablo Picasso stepped back from his easel and took a long, hard look at the painting we know as Girl before a Mirror. Deciding there was nothing more he wanted to change or to add, he recorded the day, month, and year of completion on the back of the canvas and signed it on the front, in white paint, up in the picture’s top-left corner.1 Riotous in color and chockablock with pattern, this image of a young woman and her mirror reflection was finished toward the end of a grand series of can- vases the artist had begun in December 1931, three months before.2 Its jewel tones and compartmentalized composition, with discrete areas of luminous color bounded by lines, have prompted many viewers to compare its visual effect to that of stained glass or cloisonné enamel. To draw close to the painting and scrutinize its surface, however, is to discover that, unlike colored glass, Girl before a Mirror is densely opaque, rife with clotted passages and made up of multiple complex layers, evidence of its having been worked and reworked. The subject of this painting, too, is complex and filled with contradictory symbols. The art historian Robert Rosenblum memorably described the girl’s face, at left, a smoothly painted, delicately blushing pink-lavender profile com- bined with a heavily built-up, garishly colored yellow-and-red frontal view, as “a marvel of compression” containing within itself allusions to youth and old age, sun and moon, light and shadow, and “merging . -

We Interview Luis Rojas Marcos Art PÉREZ SIQUIER

la fundación Fundación MAPFRE magazine#49 December 2019 www.fundacionmapfre.org We interview Luis Rojas Marcos Art PÉREZ SIQUIER Social Innovation PRESENTATION OF THE FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE SOCIAL INNOVATION AWARDS Road Safety THE LOOK BOTH WAYS CAMPAIGN LAUNCHED IN BOSTON Health Watch THE MILLENNIALS AND HEALTH VISITA NUESTRAS EXPOSICIONES VISIT OUR EXHIBITIONS Giovanni Boldini BOLDINI Y LA PINTURA ESPAÑOLA BOLDINI AND SPANISH PAINTING Scialle rosso [El mantón rojo], A FINALES DEL SIGLO XIX. AT THE END OF THE 19TH CENTURY. c. 1880 EL ESPÍRITU DE UNA ÉPOCA THE SPIRIT OF AN ERA Colección particular. Cortesía de Galleria Lugar Location Bottegantica, Milán Sala Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Exhibition Hall Paseo de Recoletos 23, 28004 Madrid Paseo de Recoletos 23, 28004 Madrid Fechas Dates Del 19/09/2019 al 12/01/2020 From 19/09/2019 to 12/01/2020 Horario de visitas Visiting hours Lunes de 14:00 a 20:00 h. Monday from 2 pm to 8 pm. Martes a sábado de 10:00 a 20:00 h. Tuesday to Saturday from 10 am to 8 pm. Domingos y festivos de 11:00 a 19:00 h. Sunday/holidays from 11 am to 7 pm. Acceso gratuito los lunes Free entry on Mondays Eamonn Doyle EAMONN DOYLE EAMONN DOYLE K-13 (serie irlandesa), 2018 Lugar Location Cortesía de Michael Hoppen Sala Fundación MAPFRE Fundación MAPFRE Gallery, Londres © Eamonn Doyle, cortesía Bárbara Braganza Bárbara Braganza Exhibition Hall Michael Hoppen Gallery, Londres Bárbara de Braganza, 13. 28004 Madrid Bárbara de Braganza, 13. 28004 Madrid Fechas Dates Del 12/09/2019 al 26/01/2020 From 12/09/2019 to 26/01/2020 Horario de visitas Visiting hours Lunes de 14:00 a 20:00 h. -

RUNDBRIEF FOTOGRAFIE Undbrief Fotografie, Vol

ISSN 0945-0327 Vol. 24 (2017), No. 2 [N.F. 94] RUNDBRIEF FOTOGRAFIE undbrief Fotografie, Vol. 24 (2017), No. 2 [N.F. 94] 2 [N.F. (2017), No. 24 Vol. undbrief Fotografie, R Analoge und digitale Bildmedien in Archiven und Sammlungen EIN BILD EIN BILD Michael Diers Gegenteil, jeder wird – und sei er noch so unscheinbar – ernst und Tische, Stühle und Schränke nicht als Requisiten fungie- genommen und in seiner Eigenart gewürdigt. Aus diesem ren, sondern vielmehr gemeinsam als Akteure in einem Stück wechselseitigen Vertrauen erwächst die über Jahre errungene auftreten, dessen Titelhelden das Licht und die Farbe sind und Sicherheit, immer den richtigen Standpunkt zu wählen und in welchem die (Belichtungs-)Zeit Regie führt. ZEIT/RÄUME den adäquaten atmosphärischen Ton zu treffen. Dass sich in In vielen Fällen kann man von einem zweifachen Selbst- Über die Schönheit als kritische Kategorie bei Candida Höfer den Bildern gelegentlich auch ein ironisches Augenzwinkern porträt sprechen: So wie sich die Räume häufig selbst bereits niedergelegt findet, ist Teil der Verabredung. Denn welche in den blitzblanken Terrazzo-, Marmor- oder Holzfußböden Räume, zumal wenn sie eine abwechslungsreiche Geschichte reflektieren, stellen sie sich geziemend auch vor der Kamera haben, sind ohne Fehl und Tadel, demnach ohne nachträgli- zur Schau; auf der Gegenseite künden die Bilder von der Auto- che Einbauten oder kuriose Zutaten, die sie in einem Detail rin, die durch ihre fotografische Arbeit kaum weniger augen- decouvrieren und ein wenig aus ihrem gravitätischen Gleich- fällig, wenn auch in der Regel persönlich unsichtbar, als stille gewicht bringen. Doch solch vorsichtige Kritik zielt nie auf Beobachterin und Gestalterin im Bild zugegen ist [1]. -

THE MUSEUM of MODERN ART Nov

No. 104e THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Nov. 17, 1959 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK '19, N. Y. TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5·8900 TOWARD THE "NEW" MUSEUM PHOTOGRAPHY COLLECTION CHECKLIST "AND PHOTOGRAPHY IS THE WORK OF A MACHINE" The popular conception that "photography is a mechanical process" and that "the camera cannot lie" would seem to be contradicted by these three widely divergent visualizations of the same subject by three different photographers. RICHARD AVEDON (American, born 1923) Reverend Martin Cyril n'Arcy, S. J. 1959 From tha, book Observations, Simon and Shuster, 1959 - '~ichard AVedon is a man with gifted eyes ••••Avedon is not, not very articulate: he finds his proper tongue in silence, and while maneuvering a camera - his voice, the one that speaks with admirable clarity, is the soft sound of the shutter forever freezing a moment focused by his per- ception." Truman Capote Gift of the photographer, 1959 (Please credit Simon and Schuster) ALFRED EISENSTAEDT (American, born Germany, 1898) MoMAExh_0654_NN14_703a_NN17_MasterChecklist Reverend Martin.9ltil n'ArcY,' S. 'J. 1951. "Alfred Eisenstaedt is one of the top-flight photographers on Life maga- zine ••••Eisenstaedt has here achieved intimate visualization of the ab- stract processes of thinking by means of simple, graphic portrait tech- nique." Edward Steichen Gift of the photographer, 1959. PHILIPPE HALSMAN (American, born in LatVia, 1906) Reverend Martin Cyril n'Arcy, S. J. 1958 Philippe Halsman is one of America's best known magazine photographers. He believes that the man behind the camera is more important thaJi the .'X instrument he uses - that he is the camera. -

Gotthard Schuh Vintage Prints

VINTAGE PRINTS VON GOTTHARD SCHUH Verwaltung des fotografischen Nachlasses aus Privatbesitz und Verkauf von Vintage Prints von Gotthard Schuh durch Kaspar Schuh und Claudia Schuh SCHUH, GOTTHARD * 22.12.1897, † 29.12.1969 Geboren in Berlin. 1902 Übersiedelung der Familie in die Schweiz nach Aarau. Bis 2016 Besuch der Kunstgewerbeschule Basel mit dem Ziel, Maler zu werden. Soldat 1917/18. Als Maler in Basel und Genf 1919/20, in München 1920-1926, erste Ausstellung 1922. 1926 Rückkehr in die Schweiz. Leiter eines Fotogeschäfts in Bern. Erste Fotografien 1927. Erste Veröffentlichungen 1931 in der Zürcher Illustrierten. Ausstellung als Maler 1932 in Paris. Freischaffend für Zürcher Illustrierte, neben Hans Staub und Paul Senn gehörte Schuh im folgenden Jahrzehnt zu den wichtigen Fotoreportern der Zürcher Illustrierten und trug wesentlich zur Verbreitung der sozialdokumentarischen Reportage bei. Internationale Zeitschriften wie Vu, Paris-Match, Berliner Illustrierte, Life gehörten in dieser Zeit zu seinen Auftraggebern. Reportagereisen in verschiedenen europäischen Ländern. 1938/9 Indonesienreise nach Sumatra, Java und Bali. 1941-1960 Erster Bildredaktor der Neuen Zürcher Zeitung, Aufbau der Wochenendbeilage als prominentes Forum für Fotoreportagen, wo jüngere Fotografen gefördert wurden. 1951 Mitgründer (neben Werner Bischof, Walter Läubli, Paul Senn und Jakob Tuggener) des Kollegiums Schweizerischer Photographen, das sich für eine persönlich gefärbte Autorenfotografie und die Wahrnehmung der Fotografie als eigenständige Kunstform einsetzte. -

Ausstellungen Vor Der Neueröffnung in Winterthur Im Kunsthaus Zürich Und Anderen Orten 1974– November 2003 2003 Aura – Kü

Ausstellungen vor der Neueröffnung in Winterthur im Kunsthaus Zürich und anderen Orten 1974– November 2003 2003 Aura – Künstlerportraits aus der Sammlung der Fotostiftung Schweiz Atelier-Galerie Langhans, Prag, 15. September - 18. November 2003 Tausend Blicke – Kinderporträts von Emil Brunner 1943/44 Museum Chasa Jaura, Valchava, 26. Juli - 31. August 2003 Haus für Kunst Uri, Altdorf, 13. April - 1. Juni 2003 Médiathèque Valais, Martigny, 17. Januar - 30. März 2003 Suiza Constructiva (Beitrag Fotografie) Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, 4. Februar - 28. April 2003 Jakob Tuggener – Fotografien (In Zusammenarbeit mit der J. Tuggener-Stiftung und dem Istituto Svizzero, Rom) Spacio Culturale Svizzero, Venedig, 23. Januar - 14. März 2003 2002 Guido Baselgia – Hochland Kunsthalle Erfurt, Deutschland, 15. Dezember 2002 - 19. Januar 2003 Tampere, Finnland, 28. September - 1. Dezember 2002 Tausend Blicke – Kinderporträts von Emil Brunner 1943/44 Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur, 5. Oktober - 17. November 2002 Karl Heinz Weinberger Photographers Gallery, London, 16. August - 1. Oktober 2002 Georg Vogt – Leute im Thal Photoforum Pasquart, Biel, 31. Mai - 29. September 2002 Durchs Bild zur Welt gekommen Hugo Loetscher und die Fotografie Schweizerische Landesbibliothek, Bern, 15. Februar - 11. Mai 2002 2001 Guido Baselgia – Hochland Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur, 5. Oktober - 18. November 2001 Durchs Bild zur Welt gekommen Hugo Loetscher und die Fotografie Kunsthaus Zürich, 31. August - 18. November 2001 Yvonne Griß – Von Dingen und Menschen Museum Bellpark, Kriens, 11. Mai - 8. Juli 2001 Photoforum Pasquart, Biel, 24. Februar - 24. März 2001 Roland Iselin – Human Resources Zwischenraum bei Scalo Zürich, 11. Januar - 10. März 2001 Jakob Tuggener – Fotografien La Filature, Mulhouse, 10. Januar - 11. -

Infragestellen Als Kreativer Akt Hugo Loetscher Über Robert Frank

NeuöZürcörZäitung ZEITBILDER Samstag/Sonntag, 3./4.September 2005 Nr.20577 Robert Frank, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York Memory for the Children, 2001–2002. Infragestellen als kreativer Akt Hugo Loetscher über Robert Frank Man kann nicht über die Moderne der Fotografie reden, ohne von Atelier steht für das, was sich in der Schweiz der dreissiger Jahre Der Erfolg seines Buches «Les Americains», ´ 1958 auf Franzö- Robert Frank zu sprechen, wenn mit Moderne die Jahrzehnte ge- als fotografischer Qualitätsanspruch herausgebildet hat: Sachauf- sisch und ein Jahr später auf Englisch («The Americans») erschie- meint sind, in denen die Fotografie zu ihrer eigenen Sprache ge- nahme, Dokumentarfotografie und Werbung. Wie stark diese Aus- nen, war so enorm, dass Früheres in den Hintergrund trat. Voran- funden hat – oder genauer zu ihren eigenen Sprachen. bildung das Schaffen Franks bestimmt hat, wird oft nicht zur gegangen war der Fotoband «Indios» (1956); in ihm waren neben Nun war der Eintritt von Frank in diese Modernität so eklatant, Kenntnis genommen – das gilt für den Reporter wie für den Mode- Bildern von Pierre Verger Fotos von Werner Bischof und Robert dass man darob seine Anfänge übersehen hat. Daher ist es ver- fotografen. Frank zu sehen, von den beiden Schweizern, die es als Erste zu dienstvoll, dass das Fotomuseum Winterthur und die Fotostiftung Nun kam hinzu, dass sich sein fotografisches Bewusstsein nicht internationalem Renommee brachten. Es lohnt sich, diesen Band Schweiz die Robert-Frank-Ausstellung «Storylines» um eine seiner nur im Umgang mit der eigenen Kamera schulte, sondern auch in zum Vergleich in die Hand zu nehmen, um festzustellen, welchen ersten Reportagen erweitert haben. -

Ricco Wassmer 1915–1972 His Centenary Birthday

EN Ricco Wassmer 1915–1972 His Centenary Birthday EXHIBITION GUIDE Floorplan Contents Section I (old building, basement) 1 Bremgarten—Munich—Paris 1929–1939 2 Return to Confined Circumstances 1940–1947 3 Still-Lifes 1943–1948 Basement Floor 11 5 10 4 New Horizons 1946–1950 old building 9 1 8 7 2 6 3 Basement Floor Section II (new building, basement) 4 new building 5 Cabinet of Curiosities 6 Bompré—a Castle to Himself 1950–1963 7 The Sorrow of Transience—François Mignon 1952–1954 In the Beginning was the Camera 8 The Eternal Charm of Youth—Jean Baudet 1955–1958 9 We Will Never Know 1958–1963 10 Ropraz—Paradise Unchanged 1964–1966 11 The Final Dreams 1966–1972 Biography of Ricco Wassmer 1915–1972 A Forgotten Artist Border Crosser The Kunstmuseum Bern is mounting a comprehensive retrospective scious, the various layers of reality and time seem interwoven. Sen- on Ricco Wassmer (whose real name was Erich Hans Wassmer, 1915– suality and escape from the realities of life, intimacy and distance 1972) on the occasion of this Swiss painter and photographer’s 100th combine in his painted fantasies to form a brittle unity. birthday. With seemingly surreal arrangements he produced a unique With over 200 loans, especially from private collectors, the show oeuvre that can be roughly classified as somewhere between naive is providing a broad overview of Ricco’s entire oeuvre. Many of the painting, new objectivity, and magic realism. Key themes in the art- artworks were never before shown in public—and newly discovered ist’s work are loss of the carefree years of childhood, slender youths, pieces are among them too. -

Cinéportrait Villi Hermann

Cinéportrait VILLI HERMANN © A. Merker Photo: Cinéportraits – Una pubblicazione dell‘agenzia di promozione SWISS FILMS. In caso di utilizzo del testo o di parti di esso da parte di terzi è obbligatoria l‘indicazione della fonte. 2005, aggiornato nel 2015. www.swissfilms.ch BIOGRAPHY Villi Hermann, madre ticinese e padre svizzero tedesco, stu- dia arti figurative a Lucerna, sua città natale, a Krefeld e poi a Parigi. Negli anni 1964–65 espone a Lucerna e Lugano VILLI i suoi primi quadri e disegni HERMANN e le sue litografie. In seguito frequenta la London School of Filmtechnique (LSFT), dove si diploma nel 1969. Tornato in Svizzera (dapprima a Zurigo, poi in Ticino), inizia a Oltre le frontiere lavorare come cineasta indi- pen dente, collaborando paralle- i madre malcantonese ma originario della Svizzera tedesca, dove è cresciuto e si è forma- lamente con la Televisione sviz- zera DRS Zürich e RTSI Lugano D to prima di recarsi a studiare cinema a Londra, già coinvolto direttamente nell’ambiente per documentari e servizi culturali. Dal 1976 lavora con il del cine ma svizzero negli anni del maggior impegno sociale, Hermann giunge in Ticino negli anni Filmkollektiv di Zurigo. Nel 1981 fonda la propria casa di pro- Settanta (nel decennio pre cedente svolge il lavoro di grafico, firmando anche alcune mostre) e duzione, Imago Film, a Lugano. Realizza la prima coproduzione nel 1974 realizza il mediometraggio Cerchiamo per subito operai, offriamo..., un’indagine sulla ufficiale con l’Italia Bankomatt. Vive nel Malcantone. Membro situazione dei lavoratori pendolari che entrano in Svizzera quotidianamente. Nel 1977 in San dell’Associazione svizzera regia e sceneggiatura film Gottardo, un film documentario e insieme di finzione è ancora il mondo del lavoro il tema cen- ARF/FDS, dell’Associazione Film e Audiovisivi Ticino AFAT trale. -

Gotthard Schuh in Dutch East-India 1938

Gotthard Schuh in Dutch East-India 1940 A short choice from his black-and-white photography drs (Msc) Dirk Teeuwen Account The aim of this article is to attract attention to the work of Gotthard Schuh and specially to his album “Islands of the Gods”. I tried to illustrate the magnificent beauty of this book. For the purpose of this intention I included some photographs as examples in this article. I hope that I can give a clear contribution to the importance of Schuh’s work for Dutch East-Indian and Indonesian history. Nothing in this article is available on request. Nothing is available for reproduction. Schuh, Gotthard: Eilanden der Goden (Islands of the Gods); Amsterdam 1943 For sale in antiquarian bookshops in The Netherlands Gotthard Schuh Gotthard Schuh was born in Berlin as a son of Swiss born parents December 22nd 1897 and died in Küsnacht, Switzerland, December 29th 1969. In 1902 the family moved to Arau, Switzerland. In Arau Gotthard Schuh went to primary school as well as high school. During his high school period Schuh began to paint. Finally he graduated from Vocational School in Basel in 1916. In 1917-1918 Schuh was enlisted as a soldier in the Swiss army. From 1919 he lived as a painter in Basel, Geneva and Italy. After his marriage in 1927 he moved to Zürich and started to photograph for magazines such as Zürcher Illustrierte, Paris Match and Life. His work led him throughout Europe. In 1937-1938 he paid a visit to Dutch East-India (Indonesia) and published the photographic results of this journey afterwards.