The Pivot of the World__By Blake Stimson.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henryk Berlewi

HENRYK BERLEWI HENRYK © 2019 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2019 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F T HENRYK © O H C E M N 2019 A E R M R R I E L L B . C BERLEWI (1894-1967) HENRYK BERLEWI (1894-1967) Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait,1922. Gouache on paper. Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait, 1946. Pencil on paper. Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Design and production by Jolie Simpson Edited by Dr. Karen Kettering, Independent Scholar, Seattle, USA Copy edited by Lisa Berman Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2019 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2019 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Élément de la Mécano- Facture, 1923. Gouache on paper, 21 1/2 x 17 3/4” (55 x 45 cm) Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the staf of the Frick Collection Library and of the New York Public Library (Art and Architecture Division) for assisting with research for this publication. We would like to thank Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz and Julia Gutsch for assisting in editing the titles in Polish, French, and German languages, as well as Gershom Tzipris for transliteration of titles in Yiddish. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Marek Bartelik, author of Early Polish Modern Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) and Adrian Sudhalter, Research Curator of the Merrill C. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

Collection 1880S–1940S, Floor 5 Checklist

The Museum of Modern Art Fifth Floor, 1880s-1940s 5th Fl: 500, Constantin Brancusi Constantin Brâncuși Bird in Space 1928 Bronze 54 x 8 1/2 x 6 1/2" (137.2 x 21.6 x 16.5 cm) Given anonymously 153.1934 Fall 19 - No restriction Constantin Brâncuși Fish Paris 1930 Blue-gray marble 21 x 71 x 5 1/2" (53.3 x 180.3 x 14 cm), on three-part pedestal of one marble 5 1/8" (13 cm) high, and two limestone cylinders 13" (33 cm) high and 11" (27.9 cm) high x 32 1/8" (81.5 cm) diameter at widest point Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange) 695.1949.a-d Fall 19 - No restriction Constantin Brâncuși Mlle Pogany version I, 1913 (after a marble of 1912) Bronze with black patina 17 1/4 x 8 1/2 x 12 1/2" (43.8 x 21.5 x 31.7 cm), on limestone base 5 3/4 x 6 1/8 x 7 3/8" (14.6 x 15.6 x 18.7 cm) 17 1/4 × 8 1/2 × 12 1/2" (43.8 × 21.6 × 31.8 cm) Other (bronze): 17 1/4 × 8 1/2 × 12 1/2" (43.8 × 21.6 × 31.8 cm) 5 3/4 × 6 1/8 × 7 3/8" (14.6 × 15.6 × 18.7 cm) Other (approx. weight): 40 lb. (18.1 kg) Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange) 2.1953 Fall 19 - No restriction Constantin Brâncuși Maiastra 1910-12 White marble 22" (55.9 cm) high, on three-part limestone pedestal 70" (177.8 cm) high, of which the middle section is Double Caryatid, c. -

Leseprobe 9783791385280.Pdf

Our Bauhaus Our Bauhaus Memories of Bauhaus People Edited by Magdalena Droste and Boris Friedewald PRESTEL Munich · London · New York 7 Preface 11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those Days Photography The Idea of the at the Bauhaus Bauhaus: The Battle 16 for New Educational Josef Albers 76 Foundations Thirteen Years Howard at the Bauhaus Dearstyne 131 Mies van der Rohe’s Hans 22 Teaching at the Haffenrichter Alfred Arndt Bauhaus in Dessau Lothar Schreyer how i got to the and the Bauhaus bauhaus in weimar 83 Stage Walter Dexel 30 The Bauhaus 137 Herbert Bayer Style: a Myth Gustav Homage to Gropius Hassenpflug 89 A Look at the Bauhaus 33 Lydia Today Hannes Beckmann Driesch-Foucar Formative Years Memories of the 139 Beginnings of the Fritz Hesse 41 Dornburg Pottery Dessau Max Bill Workshop of the State and the Bauhaus the bauhaus must go on Bauhaus in Weimar, 1920–1923 145 43 Hubert Hoffmann Sándor Bortnyik 100 the revival of the Something T. Lux Feininger bauhaus after 1945 on the Bauhaus The Bauhaus: Evolution of an Idea 150 50 Hubert Hoffmann Marianne Brandt 117 the dessau and the Letter to the Max Gebhard moscow bauhaus Younger Generation Advertising (VKhUTEMAS) and Typography 55 at the Bauhaus 156 Hin Bredendieck Johannes Itten The Preliminary Course 121 How the Tremendous and Design Werner Graeff Influence of the The Bauhaus, Bauhaus Began 64 the De Stijl group Paul Citroen in Weimar, and the 160 Mazdaznan Constructivist Nina Kandinsky at the Bauhaus Congress of 1922 Interview 167 226 278 Felix Klee Hannes -

Robert Frank Memories 12/09/2020 — 10/01/2021

Robert Frank Memories 12/09/2020 — 10/01/2021 Robert Frank, who was born in Zurich in 1924 and died last year in Canada, is widely regarded as one of the most important photographers of our time. Over the course of decades, he has expanded the boundaries of photography and explored its narrative potential like no other. Robert Frank travelled thousands of miles between the American East and West Coasts in the mid-1950s, going through nearly 700 films in the process. A selection of 83 black-and-white images from this blend of diary, sombre social portrait and photographic road movie would leave its mark on generations of photographers to come. The photobook The Americans was first published in Paris, followed by the US in 1959 – with an introduction by Beat writer Jack Kerouac, no less. Off-kilter compositions, cut-off figures and blurred motion marked a new photographic style teetering between documentation and narration that would have a profound impact on postwar photography. It is quite possibly the single most influential book in the history of photography; however, rather than being a spontaneous stroke of genius, Frank had worked on his subjective visual language for years. Many of his photographs from Switzerland, Europe and South America, as well as his rarely shown works from the USA in the early 1950s, are on a par with the famous classics from The Americans. The photographer’s early work, which remained unpublished for editorial reasons and is therefore little known to this day, reveals connections to those iconic pictures that still define our image of America, even today. -

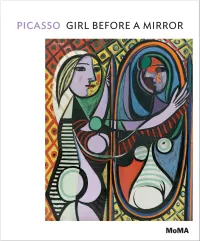

Picasso: Girl Before a Mirror

PICASSO GIRL BEFORE A MIRROR ANNE UMLAND THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK At some point on Wednesday, March 14, 1932, Pablo Picasso stepped back from his easel and took a long, hard look at the painting we know as Girl before a Mirror. Deciding there was nothing more he wanted to change or to add, he recorded the day, month, and year of completion on the back of the canvas and signed it on the front, in white paint, up in the picture’s top-left corner.1 Riotous in color and chockablock with pattern, this image of a young woman and her mirror reflection was finished toward the end of a grand series of can- vases the artist had begun in December 1931, three months before.2 Its jewel tones and compartmentalized composition, with discrete areas of luminous color bounded by lines, have prompted many viewers to compare its visual effect to that of stained glass or cloisonné enamel. To draw close to the painting and scrutinize its surface, however, is to discover that, unlike colored glass, Girl before a Mirror is densely opaque, rife with clotted passages and made up of multiple complex layers, evidence of its having been worked and reworked. The subject of this painting, too, is complex and filled with contradictory symbols. The art historian Robert Rosenblum memorably described the girl’s face, at left, a smoothly painted, delicately blushing pink-lavender profile com- bined with a heavily built-up, garishly colored yellow-and-red frontal view, as “a marvel of compression” containing within itself allusions to youth and old age, sun and moon, light and shadow, and “merging . -

Artists' Books : a Critical Anthology and Sourcebook

Anno 1778 PHILLIPS ACADEMY OLIVER-WENDELL-HOLMES % LI B R ARY 3 #...A _ 3 i^per ampUcm ^ -A ag alticrxi ' JZ ^ # # # # >%> * j Gift of Mark Rudkin Artists' Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook ARTISTS’ A Critical Anthology Edited by Joan Lyons Gibbs M. Smith, Inc. Peregrine Smith Books BOOKS and Sourcebook in association with Visual Studies Workshop Press n Grateful acknowledgement is made to the publications in which the following essays first appeared: “Book Art,” by Richard Kostelanetz, reprinted, revised from Wordsand, RfC Editions, 1978; “The New Art of Making Books,” by Ulises Carrion, in Second Thoughts, Amsterdam: VOID Distributors, 1980; “The Artist’s Book Goes Public,” by Lucy R. Lippard, in Art in America 65, no. 1 (January-February 1977); “The Page as Al¬ ternative Space: 1950 to 1969,” by Barbara Moore and Jon Hendricks, in Flue, New York: Franklin Furnace (December 1980), as an adjunct to an exhibition of the same name; “The Book Stripped Bare,” by Susi R. Bloch, in The Book Stripped Bare, Hempstead, New York: The Emily Lowe Gallery and the Hofstra University Library, 1973, catalogue to an exhibition of books from the Arthur Cohen and Elaine Lustig col¬ lection supplemented by the collection of the Hofstra Fine Arts Library. Copyright © Visual Studies Workshop, 1985. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except in the case of brief quotations in reviews and critical articles, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Reproduction in Lee Friedlander's Early Photobooks

Emily H. Cohen Arbus, Friedlander, Winogrand Spring 2014 Professor Slifkin “Beautiful to Open and Pleasurable to Leaf Through:”1 The Art and Craft of Reproduction in Lee Friedlander’s Early Photobooks In the 1970s, a photomechanical reproduction revolution was underway as printers, such as Richard Benson of the Meridan Gravure Company in Connecticut, were experimenting with methods to translate the tonal complexities of silver gelatin photographs into ink on paper. In doing so, they would further the role of photobooks as an important component of modern photography. Photographer Lee Friedlander had been shooting film since the 1950s, but it was not until the ‘70s that he became interested in putting his work into book format. For his first solo book project, Self Portrait, he was teamed up with Benson, and as a collaborative team they helped revolutionize offset lithographic printing for the world of photography. Friedlander has prolifically produced photobooks ever since, and his output raises questions about the nature of reproduction, the role of craft in the art of photographs in ink, and how the book format necessarily changes the viewing experience for photography. When photographs are brought together as a collection, they resonate with each other, providing additional information and meaning for each individual image; the whole is greater 1 Parr, 4. “The combination of remarkable images and good design in a book that is beautiful to open and pleasurable to leaf through is an ideal way of conveying a photographer’s ideas and statements.” Cohen, "2 than the sum of its parts. This notion, according to Peter Galassi in his essay for Friedlander’s 2004 monograph publication, is fundamental to modern photography: “Considered one by one, some of the pictures are inevitably better than others, but the sense of the whole depends upon the profusion of its parts.”2 To further the connection, photographs can be literally bound together as pages of a photobook; the physical connection makes the collective meaning paramount. -

We Interview Luis Rojas Marcos Art PÉREZ SIQUIER

la fundación Fundación MAPFRE magazine#49 December 2019 www.fundacionmapfre.org We interview Luis Rojas Marcos Art PÉREZ SIQUIER Social Innovation PRESENTATION OF THE FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE SOCIAL INNOVATION AWARDS Road Safety THE LOOK BOTH WAYS CAMPAIGN LAUNCHED IN BOSTON Health Watch THE MILLENNIALS AND HEALTH VISITA NUESTRAS EXPOSICIONES VISIT OUR EXHIBITIONS Giovanni Boldini BOLDINI Y LA PINTURA ESPAÑOLA BOLDINI AND SPANISH PAINTING Scialle rosso [El mantón rojo], A FINALES DEL SIGLO XIX. AT THE END OF THE 19TH CENTURY. c. 1880 EL ESPÍRITU DE UNA ÉPOCA THE SPIRIT OF AN ERA Colección particular. Cortesía de Galleria Lugar Location Bottegantica, Milán Sala Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Exhibition Hall Paseo de Recoletos 23, 28004 Madrid Paseo de Recoletos 23, 28004 Madrid Fechas Dates Del 19/09/2019 al 12/01/2020 From 19/09/2019 to 12/01/2020 Horario de visitas Visiting hours Lunes de 14:00 a 20:00 h. Monday from 2 pm to 8 pm. Martes a sábado de 10:00 a 20:00 h. Tuesday to Saturday from 10 am to 8 pm. Domingos y festivos de 11:00 a 19:00 h. Sunday/holidays from 11 am to 7 pm. Acceso gratuito los lunes Free entry on Mondays Eamonn Doyle EAMONN DOYLE EAMONN DOYLE K-13 (serie irlandesa), 2018 Lugar Location Cortesía de Michael Hoppen Sala Fundación MAPFRE Fundación MAPFRE Gallery, Londres © Eamonn Doyle, cortesía Bárbara Braganza Bárbara Braganza Exhibition Hall Michael Hoppen Gallery, Londres Bárbara de Braganza, 13. 28004 Madrid Bárbara de Braganza, 13. 28004 Madrid Fechas Dates Del 12/09/2019 al 26/01/2020 From 12/09/2019 to 26/01/2020 Horario de visitas Visiting hours Lunes de 14:00 a 20:00 h. -

Teil 1 – Beispiele Bis 1945

Diagramme in der Kunst / Praktiken des Diagrammatischen in der Kunst Anmerkung: Für die ‚Diagrammatik der Kunst‘, scheint es mir (aufgrund der zu verstreuten Materiallage) noch zu früh zu sein. Anlaß Jahresthema 2013 – Im Vorfeld zur ‚Diagrammatik der Typographie‘ [email protected] Version 5.0 10.3.2013 Teil 1 – Beispiele bis 1945 Dank an: Dietmar Offenhuber, Astrit Schmidt-Burkhardt, Boris Nieslony, Dieter Mersch, Sybille Krämer, Nikolaus Gansterer, Paolo Bianchi, Gert Hasenhütl, Wolfgang Pircher, Thomas Thiel, Ruth Schnell, Renate Herter, das LBI, ars electronica team, Peter Weibel, OK team, Udo Wid, Rainer Zendron, Walter Pamminger, Kirsten Wagner, Karin Bruns, Thomas Goldstrasz, Monika Fleischmann, Philippe Rekacewicz, Lev Manovich, Karin Bruns, Sabine Zimmermann, Katja Mayer, Tim Otto Roth, Franz Reitinger, CONT3XT.NET, TransPublic Linz, servus Linz, Gitti Vasicek, Fadi Dorninger, Margit Rosen, Herbert W. Franke, Georg Ritter, Norbert Artner, Annamária Szöke, Laszlo Beke, Charles Kaltenbacher, Michael Rottmann, Josef Ramaseder Kontext: Tagung – Schaubilder – Bilder als Wissensmodelle http://www.bielefelder-kunstverein.de/veranstaltungen/schaubilder-bilder-als-wissensmodelle.html Vergleich dazu: Vortrag von Susanne Leeb (Merz Akademie Stuttgart): Die Diagrammatik der Kunst „Susanne Leeb stellte Theorien und Praktiken des Diagrammatischen in der Kunst vor, die zum Teil zum Zweck der Bildung von Gegeninformationen eingesetzt werden. Ausgehend von philosophischen Reflexionen über das Diagramm bei Gilles Deleuze und Felix Guattari -

Exhibition Handout

Balthasar Burkhard Part I (Fotostiftung Schweiz) 10.02.–21.05.2018 Early Photographs Balthasar Burkhard was just eight years old when his father With this major retrospective, Fotomuseum Winterthur gave him a camera to take along on a school excursion. and Fotostiftung Schweiz pay homage to the Swiss artist Burkhard himself describes this early experience with the Balthasar Burkhard (1944–2010). His oeuvre is almost un- camera as the starting point of his career. It was also his paralleled in the way it reflects not only the self-invention father who suggested an apprenticeship with Kurt Blum, one of a photographer, but also the emancipation of photo- of Switzerland’s foremost photographers, ranking along- graphy as an artistic medium in its own right during the side Paul Senn, Jakob Tuggener and Gotthard Schuh. Blum second half of the twentieth century. taught the young Balz, as he was nicknamed, all the finer points of darkroom technique as well as the art of large- Together, the two institutions chart the many and varied format photography. The earliest work from Burkhard’s ap- facets of Burkhard’s career, step by step. Fotostiftung pre- prentice years is a reportage of the school, in the form of a sents early works from the days of his apprenticeship with book, while his documentation of the Distelzwang Society’s Kurt Blum and his first independent documentary photo- historic guildhall in the old quarter of Bern was clearly a graphs. The exhibition also traces Burkhard’s role as a photo- lesson in architectural photography. Yet, no sooner had he grapher alongside the curator Harald Szeemann and captur- completed his apprenticeship than Burkhard was already ing images of Bern’s bohemian scene in the 1960s and 1970s. -

RUNDBRIEF FOTOGRAFIE Undbrief Fotografie, Vol

ISSN 0945-0327 Vol. 24 (2017), No. 2 [N.F. 94] RUNDBRIEF FOTOGRAFIE undbrief Fotografie, Vol. 24 (2017), No. 2 [N.F. 94] 2 [N.F. (2017), No. 24 Vol. undbrief Fotografie, R Analoge und digitale Bildmedien in Archiven und Sammlungen EIN BILD EIN BILD Michael Diers Gegenteil, jeder wird – und sei er noch so unscheinbar – ernst und Tische, Stühle und Schränke nicht als Requisiten fungie- genommen und in seiner Eigenart gewürdigt. Aus diesem ren, sondern vielmehr gemeinsam als Akteure in einem Stück wechselseitigen Vertrauen erwächst die über Jahre errungene auftreten, dessen Titelhelden das Licht und die Farbe sind und Sicherheit, immer den richtigen Standpunkt zu wählen und in welchem die (Belichtungs-)Zeit Regie führt. ZEIT/RÄUME den adäquaten atmosphärischen Ton zu treffen. Dass sich in In vielen Fällen kann man von einem zweifachen Selbst- Über die Schönheit als kritische Kategorie bei Candida Höfer den Bildern gelegentlich auch ein ironisches Augenzwinkern porträt sprechen: So wie sich die Räume häufig selbst bereits niedergelegt findet, ist Teil der Verabredung. Denn welche in den blitzblanken Terrazzo-, Marmor- oder Holzfußböden Räume, zumal wenn sie eine abwechslungsreiche Geschichte reflektieren, stellen sie sich geziemend auch vor der Kamera haben, sind ohne Fehl und Tadel, demnach ohne nachträgli- zur Schau; auf der Gegenseite künden die Bilder von der Auto- che Einbauten oder kuriose Zutaten, die sie in einem Detail rin, die durch ihre fotografische Arbeit kaum weniger augen- decouvrieren und ein wenig aus ihrem gravitätischen Gleich- fällig, wenn auch in der Regel persönlich unsichtbar, als stille gewicht bringen. Doch solch vorsichtige Kritik zielt nie auf Beobachterin und Gestalterin im Bild zugegen ist [1].