Greek Chronography and the List of Roman Magistrates Gerding, Henrik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

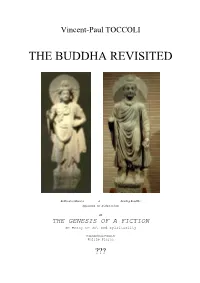

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

Ovid, Fasti 1.63-294 (Translated By, and Adapted Notes From, A

Ovid, Fasti 1.63-294 (translated by, and adapted notes from, A. S. Kline) [Latin text; 8 CE] Book I: January 1: Kalends See how Janus1 appears first in my song To announce a happy year for you, Germanicus.2 Two-headed Janus, source of the silently gliding year, The only god who is able to see behind him, Be favourable to the leaders, whose labours win Peace for the fertile earth, peace for the seas: Be favourable to the senate and Roman people, And with a nod unbar the shining temples. A prosperous day dawns: favour our thoughts and speech! Let auspicious words be said on this auspicious day. Let our ears be free of lawsuits then, and banish Mad disputes now: you, malicious tongues, cease wagging! See how the air shines with fragrant fire, And Cilician3 grains crackle on lit hearths! The flame beats brightly on the temple’s gold, And spreads a flickering light on the shrine’s roof. Spotless garments make their way to Tarpeian Heights,4 And the crowd wear the colours of the festival: Now the new rods and axes lead, new purple glows, And the distinctive ivory chair feels fresh weight. Heifers that grazed the grass on Faliscan plains,5 Unbroken to the yoke, bow their necks to the axe. When Jupiter watches the whole world from his hill, Everything that he sees belongs to Rome. Hail, day of joy, and return forever, happier still, Worthy to be cherished by a race that rules the world. But two-formed Janus what god shall I say you are, Since Greece has no divinity to compare with you? Tell me the reason, too, why you alone of all the gods Look both at what’s behind you and what’s in front. -

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina Abstract The Roman calendar was first developed as a lunar | 290 calendar, so it was difficult for the Romans to reconcile this with the natural solar year. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the calendar, creating a solar year of 365 days with leap years every four years. This article explains the process by which the Roman calendar evolved and argues that the reason February has 28 days is that Caesar did not want to interfere with religious festivals that occurred in February. Beginning as a lunar calendar, the Romans developed a lunisolar system that tried to reconcile lunar months with the solar year, with the unfortunate result that the calendar was often inaccurate by up to four months. Caesar fixed this by changing the lengths of most months, but made no change to February because of the tradition of intercalation, which the article explains, and because of festivals that were celebrated in February that were connected to the Roman New Year, which had originally been on March 1. Introduction The reason why February has 28 days in the modern calendar is that Caesar did not want to interfere with festivals that honored the dead, some of which were Past Imperfect 15 (2009) | © | ISSN 1711-053X | eISSN 1718-4487 connected to the position of the Roman New Year. In the earliest calendars of the Roman Republic, the year began on March 1, because the consuls, after whom the year was named, began their years in office on the Ides of March. -

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Poetic Difficulty in the Gemini Myth of Fasti 5

Poetic Difficulty in the Gemini Myth of Fasti 5 From the beginning of the Fasti (1.295-6), Ovid makes clear that the stars form an integral part of his calendrical poem. For some time, scholarship was disappointed in the inaccuracies of Ovid’s astronomy. He often confuses risings and settings, sometimes by a forgivable amount of days, sometimes by an inexplicably large number of months. Recently, scholars have tended to look more generously on these scientifically incorrect star placements and have sought to explain their presence thematically within the Fasti (Gee 2000; Newlands 1995; Robinson 2011). In light of this, this paper explores three thematic readings of the Gemini story (5.693-720): programmatic concerns, metapoetics, and political context. These readings help reveal the difficulty Ovid’s poetry faces and exemplifies the creative ways Ovid adheres to and adapts his project. I begin by examining the three Greek sources for the myth of the Gemini: Pindar, Apollodorus, and Theocritus. Although Ovid follows the basic narrative framework presented by these sources, he departs by emphasizing the story as an aetion of the constellation and love as the motivation of the brothers’ battle. Throughout the Fasti, Ovid tries to maintain his programmatic dichotomy of arma against sidera and amor (Hinds 1992). Ultimately, this dichotomy breaks down in Fasti 5 with the death of the peaceful poet Chiron and the entrance of Mars Ultor. The separation of stars and weapons collapses in this catasterism myth because of its graphic battle scene. To try to rehabilitate this myth and his poem, Ovid turns to his other programmatic concern, love. -

The Military Reforms of Gaius Marius in Their Social, Economic, and Political Context by Michael C. Gambino August, 2015 Directo

The Military Reforms of Gaius Marius in their Social, Economic, and Political Context By Michael C. Gambino August, 2015 Director of Thesis: Dr. Frank Romer Major Department: History Abstract The goal of this thesis is, as the title affirms, to understand the military reforms of Gaius Marius in their broader societal context. In this thesis, after a brief introduction (Chap. I), Chap. II analyzes the Roman manipular army, its formation, policies, and armament. Chapter III examines Roman society, politics, and economics during the second century B.C.E., with emphasis on the concentration of power and wealth, the legislative programs of Ti. And C. Gracchus, and the Italian allies’ growing demand for citizenship. Chap. IV discusses Roman military expansion from the Second Punic War down to 100 B.C.E., focusing on Roman military and foreign policy blunders, missteps, and mistakes in Celtiberian Spain, along with Rome’s servile wars and the problem of the Cimbri and Teutones. Chap. V then contextualizes the life of Gaius Marius and his sense of military strategy, while Chap VI assesses Marius’s military reforms in his lifetime and their immediate aftermath in the time of Sulla. There are four appendices on the ancient literary sources (App. I), Marian consequences in the Late Republic (App. II), the significance of the legionary eagle standard as shown during the early principate (App. III), and a listing of the consular Caecilii Metelli in the second and early first centuries B.C.E. (App. IV). The Marian military reforms changed the army from a semi-professional citizen militia into a more professionalized army made up of extensively trained recruits who served for longer consecutive terms and were personally bound to their commanders. -

Are a Thousand Words Worth a Picture?: an Examination of Text-Based Monuments in the Age

Are a Thousand Words Worth a Picture?: An Examination of Text-Based Monuments in the Age of Augustus Augustus is well known for his exquisite mastery of propaganda, using monuments such as the Ara Pacis, the summi viri, and his eponymous Forum to highlight themes of triumph, humility, and the monumentalization of Rome. Nevertheless, Augustus’ use of the written word is often overlooked within his great program, especially the use of text-based monuments to enhance his message. The Fasti Consulares, the Fasti Triumphales, the Fasti Praenestini, and the Res Gestae were all used to supplement his better-known, visual iconography. A close comparison of this group of text-based monuments to the Ara Pacis, the Temple of Mars Ultor, and the summi viri illuminates the persistence of Augustus' message across both types of media. This paper will show how Augustus used text-based monuments to control time, connect himself to great Roman leaders of the past, selectively redact Rome’s recent history, and remind his subjects of his piety and divine heritage. The Fasti Consulares and the Fasti Triumphales, collectively referred to as the Fasti Capitolini have been the subject of frequent debate among Roman archaeologists, such as L.R. Taylor (1950), A. Degrassi (1954), F. Coarelli (1985), and T.P. Wiseman (1990). Their interest has been largely in where the Fasti Capitolini were displayed after Augustus commissioned the lists’ creation, rather than how the lists served Augustus’ larger purposes. Many scholars also study the Fasti Praenestini; yet, it is usually in the context of Roman calendars generally, and Ovid’s Fasti specifically (G. -

An Examination of the Fasti Praenestini Julia C

The Roman Calendar as an Expression of Augustan Culture: An Examination of the Fasti Praenestini Julia C. Hernández Around the year 6 AD, the Roman grammarian Marcus Verrius Flaccus erected a calendar in the forum of his hometown of Praeneste. The fragments which remain of his work are unique among extant examples of Roman fasti, or calendars. They are remarkable not only because of their indication that Verrius Flaccus’ Fasti Praenestini was considerably larger in physical size than the average Roman fasti, but also because of the richly detailed entries for various days on the calendar, which are substantially longer and more informative than those found on any extant calendar inscriptions. The frequent mentions of Augutus in the entries of the Fasti Praenestini, in addition to Verrius Flaccus’ personal relationship with Augustus as related by Suetonius (Suet. Gram. 17), have led some scholars, most notably Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, to interpret the creation of the Fasti Praenestini as an act of propaganda supporting the new Augustan regime.1 However, this limited interpretation fails to take into account the implications of this calendar’s unique form and content. A careful examination of the Fasti Praenestini reveals that its unusual character reflects the creative experimentation of Marcus Verrius Flaccus, the individual who created it, and the broad interests of the Roman public, by whom it was to be viewed. The uniquness of the Fasti Praenestini among inscribed calendars is matched by Ovid’s literary expression of the calendar composed in elegiac couplets. This unprecedented literary approach to the calendar has garnered much more attention from scholars over the years than has the Fasti Praenestini. -

Title Page Echoes of the Salpinx: the Trumpet in Ancient Greek Culture

Title Page Echoes of the salpinx: the trumpet in ancient Greek culture. Carolyn Susan Bowyer. Royal Holloway, University of London. MPhil. 1 Declaration of Authorship I Carolyn Susan Bowyer hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Echoes of the salpinx : the trumpet in ancient Greek culture. Abstract The trumpet from the 5th century BC in ancient Greece, the salpinx, has been largely ignored in modern scholarship. My thesis begins with the origins and physical characteristics of the Greek trumpet, comparing trumpets from other ancient cultures. I then analyse the sounds made by the trumpet, and the emotions caused by these sounds, noting the growing sophistication of the language used by Greek authors. In particular, I highlight its distinctively Greek association with the human voice. I discuss the range of signals and instructions given by the trumpet on the battlefield, demonstrating a developing technical vocabulary in Greek historiography. In my final chapter, I examine the role of the trumpet in peacetime, playing its part in athletic competitions, sacrifice, ceremonies, entertainment and ritual. The thesis re-assesses and illustrates the significant and varied roles played by the trumpet in Greek culture. 3 Echoes of the salpinx : the trumpet in ancient Greek culture Title page page 1 Declaration of Authorship page 2 Abstract page 3 Table of Contents pages -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th.