'Ecclesianarchy': Excursions Into Deconstructive Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement'

H-Peace Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement' Review published on Monday, March 1, 2004 Thomas F. Curran. Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement. New York: Fordham University Press, 2003. xv + 228 pp. $45.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8232-2210-0. Reviewed by Peter Brock (Professor Emeritus of History, University of Toronto)Published on H- Peace (March, 2004) Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Thomas Curran's monograph originated in a Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Notre Dame but it has been much revised since. The book's clearly written and well-constructed narrative revolves around the person of an obscure package woolen commission merchant from Philadelphia named Alfred Henry Love (1830-1913), a radical pacifist activist who was also a Quaker in all but formal membership. Love is the key figure in the book, binding Curran's chapters together into a cohesive whole. And Love's papers, and particularly his unpublished "Journal," which are located at the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, form the author's most important primary source: in fact, he uses no other manuscript collections, although, as the endnotes and bibliography show, he is well read in the published primary and secondary materials, including work on the general background of both the Civil War era and nineteenth-century pacifism. Curran has indeed rescued Love himself from near oblivion; there is little else on him apart from an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation by Robert W. Doherty (University of Pennsylvania, 1962). -

Historic Peace Churches People

The Consistent Life Ethic the vulnerable to only some groups of Mennonite: From Article 22 of the and the Historic Peace Churches people. Some care for the children in the Mennonite Confession of Faith - womb, children recently born with Mennonites, the Church of the Brethren, and disabilities, and the vulnerable among the ill. “Led by the Spirit, and beginning in the the Religious Society of Friends, which Yet they are not as clear about the problems church, we witness to all people that cooperated together in the "New Call to of war or the death penalty or policies that violence is not the will of God. We witness Peacemaking" project, have centuries of could help solve the problems of poverty against all forms of violence, including war experience in the insights of pacifism. This that threaten the very groups they assert among nations, hostility among races and is the understanding that violence is not protection for. They weaken their case by classes, abuse of children and women, ethical, nor is the apathy or cowardice that their inconsistency. Others are very sensitive violence between men and women, abortion, supports violence by others. Furthermore, to the problems of war and the death penalty and capital punishment.” the appearance of violence as a quick fix to and poverty while using euphemisms to problems is deceptive. Through hardened Brethren: From Pastor Wesley Brubaker, avoid the realities of feticide and infanticide, http://www.brfwitness.org/?p=390 hearts, lost opportunities, and over- and allowing the "right to die" become the simplified thinking, violence generally leads "duty to die" in a society still infested with “We seem to realize instinctively that to more problems and often exacerbates far too many prejudices against the abortion is gruesome. -

The Communicator 1

February, 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Communicator 1. Search for New February, 2017 Lead 2. a. New Lead Spirit-Guided Search for the New Lead cont’d. Minister b. February By Rev. Nayiri Karjian, Interim Lead Minister Worship [email protected] c. Shrove Tuesday “How long will you be here?” “How long will the search last?” These are some of the questions 3. a. Organist I am asked as many of you wonder about the search process. I am glad to share how the process b. Soup Fundraiser usually unfolds. c. Peanut Butter The Search Committee currently is gathering information from you, the congregation, to compile 4. Youth & Adult the Church Profile, a 20 page document that introduces our congregation to an interested Ministry candidate. Their goal is to complete the profile by the end of February. 5. The Forum The next step is to activate the listing in the UCC Ministry Opportunities 6. KC Worship http://www.ucc.org/ucc_ministry_opportunities 7. Financial Ministry or exact page http://oppsearch.ucc.org/web/searchresult.aspx?q=jobposition&v=Senior_Pastor 8. JWW Lectureship Once the listing is activated, interested candidates will send their profile/professional resume to our Search Committee via the Rocky Mountain Conference UCC. 9. Mission Giving & Outreach The Search Committee reads the profiles and responds to the candidates. They check candidates’ 10. A Peek in the Past online presence, listening to sermons or reading them, checking Facebook, and so on. They also send candidates information about our church. All communication is usually done electronically. 11. Congregational Life The committee discerns the candidates who are a good match and contacts them for interviews, usually set up via skype. -

Just the Police Function, Then a Response to “The Gospel Or a Glock?”

Just the Police Function, Then A Response to “The Gospel or a Glock?” Gerald W. Schlabach Introduction Consider this thought experiment: Adam and Eve have not yet sinned. In fact, they will not sin for a few decades and have begun their family. It is time for supper, but little Cain and his brother Abel are distracted. They bear no ill will, but their favorite pets, the lion and lamb, are particularly cute as they frolic together this afternoon. So Adam goes to find and hurry them home. With nary an unkind word and certainly no violence, he polices their behavior and orders their community life. For like every social arrangement, even this still-altogether-faithful community requires the police function too. A pacifist who does not recognize this point is likely to misconstrue everything I have written about “just policing.”1 Having lived a vocation for mediating between polarized Christian communities since my years in war- torn Central America, I expected a measure of misunderstanding when I proposed the agenda of just policing as a way to move ecumenical dialogue forward between pacifist and just war Christians, especially Mennonites and Catholics. Whoever seeks to engage the estranged in conversation simultaneously on multiple fronts will take such a risk.2 Deeply held identities are often at stake, and as much as the mediator may do to respect community boundaries, he or she can hardly help but threaten them simply by crossing back and forth. The risk of misunderstanding comes with the liminal territory, and nothing but a doggedly hopeful patience for continued conversation will minimize it. -

A Feminist Analysis of the Emerging Church: Toward Radical Participation in the Organic, Relational, and Inclusive Body of Christ

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Boston University Institutional Repository (OpenBU) Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2015 A feminist analysis of the Emerging Church: toward radical participation in the organic, relational, and inclusive body of Christ https://hdl.handle.net/2144/16295 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY Dissertation A FEMINIST ANALYSIS OF THE EMERGING CHURCH: TOWARD RADICAL PARTICIPATION IN THE ORGANIC, RELATIONAL, AND INCLUSIVE BODY OF CHRIST by XOCHITL ALVIZO B.A., University of Southern California, 2001 M.Div., Boston University School of Theology, 2007 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 © 2015 XOCHITL ALVIZO All rights reserved Approved by First Reader _________________________________________________________ Bryan Stone, Ph.D. Associate Dean for Academic Affairs; E. Stanley Jones Professor of Evangelism Second Reader _________________________________________________________ Shelly Rambo, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology Now when along the way, I paused nostalgically before a large, closed-to-women door of patriarchal religion with its unexamined symbols, something deep within me rises to cry out: “Keep traveling, Sister! Keep traveling! The road is far from finished.” There is no road ahead. We make the road as we go… – Nelle Morton DEDICATION To my Goddess babies – long may you Rage! v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has always been a work carried out en conjunto. I am most grateful to Bryan Stone who has been a mentor and a friend long before this dissertation was ever imagined. His encouragement and support have made all the difference to me. -

St. Joseph's College for Women, Tirupur, Tamilnadu

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 18:10 October 2018 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== St. Joseph’s College for Women, Tirupur, Tamilnadu R. Rajalakshmi, Editor Select Papers from the Conference Reading the Nation – The Global Perspective • Greetings from the Principal ... Rev. Sr. Dr. Kulandai Therese. A i • Editor's Preface ... R. Rajalakshmi, Assistant Professor and Head Department of English ii • Caste and Nation in Indian Society ... CH. Chandra Mouli & B. Sridhar Kumar 1-16 =============================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:10 October 2018 R. Rajalakshmi, Editor: Reading the Nation – The Global Perspective • Nationalism and the Postcolonial Literatures ... Dr. K. Prabha 17-21 • A Study of Men-Women Relationship in the Selected Novels of Toni Morrison ... G. Giriya, M.A., B.Ed., M.Phil., Ph.D. Research Scholar & Dr. M. Krishnaraj 22-27 • Historicism and Animalism – Elements of Convergence in George Orwell’s Animal Farm ... Ms. Veena SP 28-34 • Expatriate Immigrants’ Quandary in the Oeuvres of Bharati Mukherjee ... V. Jagadeeswari, Assistant Professor of English 35-41 • Post-Colonial Reflections in Peter Carey’s Journey of a Lifetime ... Meera S. Menon II B.A. English Language & Literature 42-45 • Retrieval of the Mythical and Dalit Imagination in Cho Dharman’s Koogai: The Owl ... R. Murugesan Ph.D. Research Scholar 46-50 • Racism in Nadine Gordimer’s The House Gun ... Mrs. M. Nathiya Assistant Professor 51-55 • Mysteries Around the Sanctum with Special Reference To The Man From Chinnamasta by Indira Goswami ... Mrs. T. Vanitha, M.A., M.Ed., M.Phil., Ph.D. -

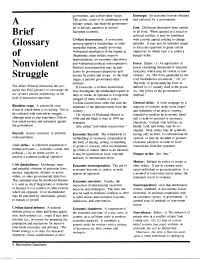

A Brief Glossary of Nonviolent Struggle

government, and subvert their troops. Embargo: An economic boycott initiated This policy, alone or in combination with and enforced by a government. A military means, has received governmen- tal or military attention in several Fast: Deliberate abstention from certain European countries. or all food. When applied in a social or Brief political conflict, it may be combined Civilian insurrection: A nonviolent with a moral appeal seeking to change Glossary uprising against a dictatorship, or other attitudes. It may also be intended simply unpopular regime, usually involving to force the opponent to grant certain widespread repudiation of the regime as objectives, in which case it is called a of illegitimate, mass strikes, massive hunger strike. demonstrations, an economic shut-down, and widespread political noncooperation. Force: Either: (1) An application of Nonviolent Political noncooperation may include power (including threatened or imposed action by government employees and sanctions, which may be violent or non- Struggle mutiny by police and troops. In the final violent). As, "the force generated by the stages, a parallel government often civil disobedience movement." Or: (2) emerges. The body or group applying force as The Albert Einstein Institution has pre- If successful, a civilian insurrection defined in (1), usually used in the plural. pared this brief glossary to encourage the may disintegrate the established regime in As, "the forces at the government's use of more precise terminology in the days or weeks, as opposed to a long-term disposal." field of nonviolent sanctions. struggle of many months or years. Civilian insurrections often end with the General strike: A work stoppage by a Bloodless coup: A successful coup departure of the deposed rulers from the majority of workers in the more impor- d'etat in which there is no killing. -

Critique of Theonomy: a Taxonomy — T. David Gordon

T. David Gordon, “Critique of Theonomy: A Taxonomy,” Westminster Theological Journal 56.1 (Spring 1994): 23-43. Critique of Theonomy: A Taxonomy — T. David Gordon I. Introduction 1. Distinguishing Theonomy from Theonomists One of the most difficult aspects of polemical theology is being sure that what is being evaluated is a distinctive viewpoint, not the individuals holding the viewpoint. Of necessity, when evaluating a given view, one examines those dimensions that distinguish it from other views. It would inevitably be lopsided, then, to confuse a criticism of a view with a criticism of those who hold it. Presumably, those who hold a distinctive view also embrace many other views that are identical with those shared by the church catholic. Individual Theonomists are not intended to be the point of an examination such as this; rather, what is evaluated is the viewpoint that distinguishes Theonomy from other approaches to biblical ethics. 2. Distinguishing Theonomy from Christian Reconstruction As socioreligious phenomena, Theonomy and Christian Reconstruction are closely related. The individuals involved in the one are ordinarily involved in the other. However, theologically and religiously they can be distinguished. Christian Reconstructionists exist in a variety of forms, and are ordinarily united in their belief that the Western world, and especially the United States, has departed from the Judeo-Christian ethical basis that once characterized its public discourse, with devastating results. Positively, Reconstructionists wish to see the United States return to a more biblical approach, or even a more Judeo-Christian approach, to the issues of civil life. Theonomy is more specific than this, though it does not disagree with it. -

An Evaluation of Theonomic Neopostmillennialism Thomas D

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Faculty Publications and Presentations School of Religion 1988 An Evaluation of Theonomic Neopostmillennialism Thomas D. Ice Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Ice, Thomas D., "An Evaluation of Theonomic Neopostmillennialism" (1988). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 103. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/103 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Religion at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Evaluation of Theonomic Neopostmillennialism Thomas D. Ice Pastor Oak Hill Bible Church, Austin, Texas Today Christians are witnessing "the most rapid cultural re alignment in history."1 One Christian writer describes the last 25 years as "The Great Rebellion," which has resulted in a whole new culture replacing the more traditional Christian-influenced Ameri can culture.2 Is the light flickering and about to go out? Is this a part of the further development of the apostasy that many premillenni- alists say is taught in the Bible? Or is this "posf-Christian" culture3 one of the periodic visitations of a judgment/salvation4 which is furthering the coming of a posfmillennial kingdom? Leaders of the 1 Marilyn Ferguson, -

The Cult of Liberation: the Berkeley Free Church and the Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 Volume 1

Dominican Scholar Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship Faculty and Staff Scholarship 1977 The Cult of Liberation: The Berkeley Free Church and The Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 volume 1 Harlan Stelmach Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies, Dominican University of California, [email protected] Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Stelmach, Harlan, "The Cult of Liberation: The Berkeley Free Church and The Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 volume 1" (1977). Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship. 52. https://scholar.dominican.edu/all-faculty/52 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1977 HARLAN DOUGLAS ANTHONY STELMACH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED : TlIE CULT OF LIIiER.'i.TION THE SEPKELEY FREE CHURCH and THE RADICAL CHURCH MOVEMENT 1967-1972 A dissertiatlon by Harlan Douglas Anthony _S_tein)ach presented to Tae Faculty of the Graduate Theological Union in partial fulfillment of the requirenents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Berkeley, California May 15, 1977 Committee Signatures: Co-Coordjnator ^ y^oV^K- t\M^ Co-Coordinator f 'il -7^ ^- With special thanks to all those who have been part of the process which helped to shape me and this dissertation: MADELYN Joy Aiiy Anne Megan Linda P. ***** Tony Fred G. John M. Edie Bill Jon Joe H. Nancy Gordon Suzanne J. Bob D. Marilena Hugh Sergio Bob C. -

THEONOMY and ESCHATOLOGY | Some Reflections on Postmillennialism

THEONOMY AND ESCHATOLOGY | Some Reflections On Postmillennialism By Richard B. Gaffin, Jr.1 Essential to the emergence of theonomy/(Christian) reconstructionism has been a revival of postmillennialism.2 Among current postmils, to be sure, there are some who are not recon- structionists, but all reconstructionists—whatever their differences—consider themselves post- mils. Or so it would have seemed until just recently with the unanticipated and apparently grow- ing impact of reconstructionist viewpoints in circles whose eschatology is characteristically premil. Still, for reconstructionism’s leading advocates, postmillennialism is plainly integral— whether logically or psychologically—to their position as a whole. Nonreconstructionist postmils would naturally deny any such connection. This chapter provides some partial, personally-tinged, yet, I hope, not entirely unhelpful reflections on the resurgent postmillennialism of the past 20-25 years. My reservations lie in at least four areas. DEFINING POSTMILLENNIALISM A large element of ambiguity cuts across much of today’s postmillennialism. Before trying to specify that ambiguity it will be helpful, historically, to give some attention to the fact that in the past, too, postmillennialism has not been the clearly defined, unambiguous position that some of its contemporary proponents make it out to be. It is fairly common to point out the inadequacy of our conventional designations pre, post, and a. But, no less commonly, in ensuing discussion that recognition recedes. As a result, efforts, for one, to distinguish between the postmil and amil positions get confused—usually, as it turns out, more than a merely terminological confusion. Who coined the term amillennial and when did it first begin to be used? Perhaps I’ve missed it somewhere, but the usual sources don’t seem to know or at least don’t say. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abhidharma, 143 atonement theory/soteriology (how Jesus’ Abraham, 13, 85 death saved humanity), 54 Abu Talib, 10 Augustine, 57–8, 69, 81 Acts of the Apostles, 47 aum (om) shanti (silence, tranquility of Afghanistan, 21, 35, 219 mind, listening to inner voice, etc.), 180 ‘afw (forgiveness), 41 Ayoub, Mahmoud M., 11, 18–19 ahimsa (nonviolence), 180–2 Aztecs, 110 Ali, Abdullah Yusuf, 17 Alvarado, Pedro, 59 ba (hegemony), 126 American Indian veterans of the US war Babylonian Talmud, 83–4, 89, 93–4 against Vietnam, 212 baoli (violence), 123 American Israel Public Affairs Committee, 100 Bar Kosiba, Simon, 93, 105 American Jewish Committee, 101 Beatitudes, 51, 69 Anabaptists, 61 Bell, Daniel, 124 Analects, 112–14, 124 Bhagavad Gita (Gita), 14, 178, 181–2, 203 Anandavan, 190–91 bhakti (personal devotion), 180 anthropocentrism, 215–17 Bhave, Vinoba, 174, 194 Anti-Defamation League, 99 Bible, 2, 14–15, 84, 87, 90–1, 143, 149, 188, anti-semitism, 63 194, 217 Arab nationalism, 45 Bodhisattva, 143, 147–50, 153 Arab Spring, 21 Bonney, Richard, 15, 23 Arab-Israeli Wars, 96–7 Brahman (ultimate reality), 4, 154, 179, 198 Ariaratne, A. T., 158, 174 Brahmins, 173, 179, 184 Arjuna, 179, 181–3, 200 Buber, Martin, 89 Art of Living Foundation, 191 Buddha, 78, 80, 135–6, 143, 145, 147–8, Ashrams: communities practicing yoga 154–5, 157, 173–4, 185, 188, and serviceCOPYRIGHTED to others, 190 Buddhism MATERIAL forms: Asita, 135 Theravada, 142–4, 148, 152, 156 Athavale, Pandurang Shastri, 194 Mahayana, 76, 142, 136, 143–4, 147–8, atman (soul), 179, 198, 203–4 150, 152, 157, 160–3, 168 Peacemaking and the Challenge of Violence in World Religions, First Edition.