Private Equity Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiba University Overview Brochure (PDF)

CHIBA UNIVERSITY 2020 2021 21 0 2 - 20 0 2 20 0 2 Contents 01 Introduction 01-1 A Message from the President ................................................................................................. 3 01-2 Chiba University Charter ........................................................................................................... 4 01-3 Chiba University Vision ............................................................................................................... 6 01-4 Chiba University Facts at a Glance .......................................................................................... 8 01-5 Organization Chart ....................................................................................................................... 10 02 Topic 02-1 Enhanced Network for Global Innovative Education —ENGINE— ................................. 12 02-2 Academic Research & Innovation Management Organization (IMO) .......................... 14 02-3 WISE Program (Doctoral Program for World-leading Innovative & Smart Education) ........................................................................................................................ 15 02-4 Creating Innovation through Collaboration with Companies ......................................... 16 02-5 Institute for Global Prominent Research .............................................................................. 17 02-6 Inter-University Exchange Project .......................................................................................... 18 02-7 Frontier -

Instructional Technology Distance Learning

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INSTRUCTIONAL TECHNOLOGY AND DISTANCE LEARNING March 2012 Volume 9 Number 3 Editorial Board Donald G. Perrin Ph.D. Executive Editor Elizabeth Perrin Ph.D. Editor-in-Chief Brent Muirhead Ph.D. Senior Editor Muhammad Betz, Ph.D. Editor ISSN 1550-6908 International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning PUBLISHER'S DECLARATION Research and innovation in teaching and learning are prime topics for the Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning (ISSN 1550-6908). The Journal was initiated in January 2004 to facilitate communication and collaboration among researchers, innovators, practitioners, and administrators of education and training involving innovative technologies and/or distance learning. The Journal is monthly, refereed, and global. Intellectual property rights are retained by the author(s) and a Creative Commons Copyright permits replication of articles and eBooks for education related purposes. Publication is managed by DonEl Learning Inc. supported by a host of volunteer editors, referees and production staff that cross national boundaries. IJITDL is committed to publish significant writings of high academic stature for worldwide distribution to stakeholders in distance learning and technology. In its first six years, the Journal logged over six million page views and more than one million downloads of Acrobat files of monthly journals and eBooks. Donald G. Perrin, Executive Editor Elizabeth Perrin, Editor in Chief Brent Muirhead, Senior Editor Muhammad Betz, Editor March -

CURRICULUM VITAE H. W. Perry, Jr. the University of Texas School Of

CURRICULUM VITAE H. W. Perry, Jr. The University of Texas School of Law 727 East Dean Keeton St. Austin, TX 78705 [email protected] (512) 232-1852 Education Ph.D., The University of Michigan, Political Science, 1987 Legal Coursework at The University of Michigan Law School M.A., The University of Michigan, Political Science B.A., with honors, Southern Methodist University, Political Science, Social Sciences, 1974 Academic Appointments University Distinguished Teaching Professor Associate Professor of Law, School of Law, 2000-present Associate Professor of Government, College of Liberal Arts, 1994-present The University of Texas at Austin Interdisciplinary professor, School of Law, The University of Texas at Austin, 1997-2000 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University, 1990-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University, 1986-1990 Instructor, Department of Political Science, College of Arts and Sciences, Washington University, 1983-1986 Lecturer, Department of Political Science, The University of Michigan, Spring/Summer 1981; Summer 1982 Visiting Appointments Distinguished Visiting Professor, LaTrobe Law School, Melbourne, Australia, June 2017, 2018 Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Centre for Law, Governance and Public Policy, Bond University, Queensland, Australia, June, 2010 Astor Visiting Lecturer, Centre for Socio-legal Studies, Oxford University, June 2000 H. W. Perry, Jr. 2 Non-academic Director of Development, S.M.U. School of Law, 1975-1977 Employment Assistant Director of Development, S.M.U., 1974-1975 Selected Administrative Founding and current Director, Combined JD/Ph.D. program in law and Responsibilites, U.T. politics . Co-Principal Investigator, Ford Foundation Grant for Difficult Dialogs Director, Texas-Oxford Law Faculty interchange 2000-2007 Chair, Public Law subfield 1994-2005 Director, Democracy in the Third Millennium Program 1997-2000 Research Areas U. -

Education and Technology in Mexico and Latin America: Outlook and Challenges

http://rusc.uoc.edu doSSIEr Education and Technology in Mexico and Latin America: Outlook and Challenges. Introduction Submitted in: May 2013 Accepted in: May 2013 Published in: July 2013 Recommended citation ONTIVEROS, Margarita; CANAY, José Raúl (2013). “Education and Technology in Mexico and Latin Ame- rica: Outlook and Challenges. Introduction”. In: “Education and Technology in Mexico and Latin Ameri- ca: Outlook and Challenges” [online dossier]. Universities and Knowledge Society Journal (RUSC). Vol. 10, No 2. pp. 407-413. UOC. [Accessed: dd/mm/yy]. <http://rusc.uoc.edu/ojs/index.php/rusc/article/view/v10n2-ontiveros-canay/v10n2-ontiveros-ca- nay-en> <http://dx.doi.org/10.7238/rusc.v10i2.1848> ISSN 1698-580X Abstract With an increasing number of young people reaching university entrance age, the demographic reality of Latin American countries is changing the face of their traditional higher education spaces. The impact is driving institutions to seek effective solutions, and technology has been identified as a ‘way forward’ in terms of offering education to the growing population of young people who want it. Technology- mediated education must therefore help to improve Latin American citizens’ quality of life. In Mexico, and since 2010, the National System of Distance Education (SINED) – an initiative led by universities interested in strengthening education mediated by information and communication technologies (ICTs) – has been exploring ways to incorporate these tools into the evolution of Mexi- can and, by extension, Latin American universities. This monographic Dossier, produced in conjunction with RUSC. Universities and Knowledge So- ciety Journal, is part of the SINED’s effort to progress towards generating information, documentation and materials to support the academic community involved in ICTs and innovation from a number of angles, including use, learning and research. -

The Miciina Hairriccibie Registration Shows 2 Guys for Each

Registration Shows 2 Guys For Each Girl University College coeds should Juniors 665 1205 uomen. For the 283 senior busi- Of the 221 students in the tcring the School of Medicine, classes, but receive no credit, Seniors 392 801 <lo well this semester in "The Unclassified 981 663 ness majors, there are only 27 School of Engineering, only 5 only 20 are women. number 75. Auditors 36 39 women. are women. Picken' and Chosen' of Males" B> March 10 there «err Specie] non-credit courses, Reason-there Total 3,566 5,681 Illl through 202. The School of Music has the In addition to these under- I.L'.Vi graduate students enrol- programs and institutes contain arc men to 1.750 graduates, 3,375 women. The School of Arts and lowest enrollment with 28 men there ere 994 students led Hut linal figures have not 1,328 evening students The en- report Registrar The released by Seeinces has 1,157 day students and 20 women. classified as new freshmen, trans- set been released. I'nlike any rollment m this area is still open. George Smith shows the follow- in; fers, and re-admitted students. Other school, the evening grad- iitul evening students. Of Only in the School of Educa- Summary totals for Srnnj enrollment are: ing for lioth daytime and eve- ii ile students these 775 .'ire males. tion do men have the advantage The Law School enrollment outnumber the Undergraduates 9247 ning undergraduate students: davtimcrs 702 to 184, with al- Graduates and professional students 1872 I Ii.-i .- .m 488 junior in with 478 males to 1,199 females reached 320 this semester. -

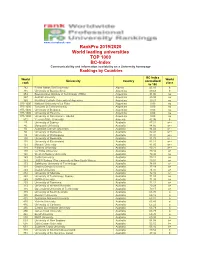

Rankpro 2019/2020 World Leading Universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and Information Availability on a University Homepage Rankings by Countries

www.cicerobook.com RankPro 2019/2020 World leading universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and information availability on a University homepage Rankings by Countries BC-Index World World University Country normalized rank class to 100 782 Ferhat Abbas Sétif University Algeria 45.16 b 715 University of Buenos Aires Argentina 49.68 b 953 Buenos Aires Institute of Technology (ITBA) Argentina 31.00 no 957 Austral University Argentina 29.38 no 969 Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina Argentina 20.21 no 975-1000 National University of La Plata Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 Torcuato Di Tella University Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Belgrano Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Palermo Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of San Andrés - UdeSA Argentina 0.00 no 812 Yerevan State University Armenia 42.96 b 27 University of Sydney Australia 87.31 a++ 46 Macquarie University Australia 84.66 a++ 56 Australian Catholic University Australia 84.02 a++ 80 University of Melbourne Australia 82.41 a++ 93 University of Wollongong Australia 81.97 a++ 100 University of Newcastle Australia 81.78 a++ 118 University of Queensland Australia 81.11 a++ 121 Monash University Australia 81.05 a++ 128 Flinders University Australia 80.21 a++ 140 La Trobe University Australia 79.42 a+ 140 Western Sydney University Australia 79.42 a+ 149 Curtin University Australia 79.11 a+ 149 UNSW Sydney (The University of New South Wales) Australia 79.01 a+ 173 Swinburne University of Technology Australia 78.03 a+ 191 Charles Darwin University Australia 77.19 -

Bank Foreclosure Law Reform and the Development of Mexico Comercio Exterior (“Foreign Trade” Magazine), Vol

ORIGINAL SPANISH VERSION . Bank Foreclosure Law Reform and the development of Mexico Comercio Exterior (“Foreign Trade” magazine), Vol. 55, Number 1, January 2005 Rosa Barrón Blando Jaime Velazquez Hernández Ricardo Zamora Mesinas* _____________ * Research Associate, AD Tec Construction Management & Consulting [email protected] Dean of the School of Economics at the Panamerican University, Mexico City [email protected] Managing Director, AD Tec Construction Management & Consulting [email protected] Current political and economic environment in Mexico The lack of results of the current Mexican administration has given rise to a generalized sentiment of frustration and disappointment in society. Great debate has occurred in all arenas regarding the causes for economic stagnation. Some blame the legislative power and its reluctance to pas the executive-proposed reforms to the energy sector, the fiscal regime, the social security and the telecommunications laws, just to mention a few. Others, mainly the parties opposite to the one currently in office, hold the executive branch of the federal government accountable for the impasse, wielding the argument that such proposals are harming to the country, lessen Mexico’s sovereignty and, generally, represent a setback to certain social “conquests”, since they do not attend to the social needs of the country. To be sure, the majority of the population only have a vague idea about the content and the intent of such reforms, thus becoming easily influenced by the disqualifying arguments brought forth by the various opposing groups. Under the present circumstances, the reform initiative for the Bank Foreclosure Law can be presented as a viable alternative for a quick approval, firstly, because of its positive effect it would have upon the economy and upon the standard of living of the population, and secondly because it may confront less political pressures in light of the lower number of groups who have expressed opposition to it. -

CTS Goes International University of St

CTS Goes International University of St. Thomas Aquinas Lecture Series Center for Thomistic Studies Each year, the Center for Thomistic Studies’ Aquinas Lecture Presents brings a distinguished member of the philosophical commu- nity to the University of St. Thomas for a talk which displays the great resources of the Thomistic philosophical tradition, ei- 2013 Aquinas Lecture ther by addressing a subject directly related to the writings of St. Thomas or some other figure in the tradition, or by addressing Rev. Kevin L. Flannery, S.J. more systematically a question of enduring philosophical impor- tance. Among the Aquinas Lecturers the Center has had the Professor of Philosophy, privilege of hosting are such renowned thinkers as Henry Ve- atch, Joseph Owens, Elizabeth Anscombe, Peter Geach, Janet Pontificia Università Gregoriana Smith, Alasdair MacIntyre, Germain Grisez, Avery Cardinal Dul- les, S.J., Msgr. John F. Wippel, Fr. Leo J. Elders, SVD, and On Archbishop J. Michael Miller. To this list the Center is very pleased to add our 2013 lecturer, Fr. Kevin Flannery, Professor of The Capacious Mind Philosophy, Pontificia Università Gregoriana. of University of St. Thomas St. Thomas Aquinas The University of St. Thomas is a private institution committed to the liberal arts and to the religious, ethical and intellectual tradition of Catholic higher education. Educating Leaders of Faith and Character Special Thanks to the following: Dr. Robert Ivany Dr. Domenic Aquila Ms. Valerie Hall Ms. Cynthia Colbert Riley Ms. Marionette Mitchell Ms. Eileen Perkins Ms. Sandra Soliz Students of the Center for Thomistic Studies Thursday, January 24, 2013 7:30 p.m. -

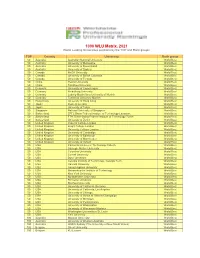

WLU Table 2021

1000 WLU Matrix. 2021 World Leading Universities positions by the TOP and Rank groups TOP Country University Rank group 50 Australia Australian National University World Best 50 Australia University of Melbourne World Best 50 Australia University of Queensland World Best 50 Australia University of Sydney World Best 50 Canada McGill University World Best 50 Canada University of British Columbia World Best 50 Canada University of Toronto World Best 50 China Peking University World Best 50 China Tsinghua University World Best 50 Denmark University of Copenhagen World Best 50 Germany Heidelberg University World Best 50 Germany Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich World Best 50 Germany Technical University Munich World Best 50 Hong Kong University of Hong Kong World Best 50 Japan Kyoto University World Best 50 Japan University of Tokyo World Best 50 Singapore National University of Singapore World Best 50 Switzerland EPFL Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne World Best 50 Switzerland ETH Zürich-Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich World Best 50 Switzerland University of Zurich World Best 50 United Kingdom Imperial College London World Best 50 United Kingdom King's College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Cambridge World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Edinburgh World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Manchester World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Oxford World Best 50 USA California Institute of Technology Caltech World Best 50 USA Carnegie -

Brandon J. Price, Ph.D. the Ben J. Rogers Chair in Entrepreneurism Of

Brandon J. Price, Ph.D. Dr. Price is a scientist, businessman and entrepreneur, with more than 30 years in the biopharmaceutical industry. He is currently Executive Vice President of Business Development at Nascent Biotech (a clinical-stage public company developing cancer biologic drugs) and, with Dr. Fernando Larios, he has formed Biogenin, S.A.P.I. de C.V., located in Guadalajara, Mexico, which is developing and licensing new human and veterinary pharmaceuticals primarily for the Latin American market. In early 2016, Dr. Price was appointed the Ben J. Rogers Chair in Entrepreneurism of the College of Business at Lamar University (Beaumont, TX), and in early 2017 was elected to the GOOSE (Grand Order of Successful Entrepreneurs) Society of Texas. Dr. Price has been CEO of GalenBio, Inc, a synthetic vaccine company, Oncometa Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a small molecule company developing cancer and metabolic disorder drugs, Cognate Therapeutics, a stem cell company, President and CEO of Goodwin Biotechnology, a biologics contract manufacturing organization and he was the first CEO of CropTech Corporation, where he wrote the company’s business plan and raised its first round of private financing. Formerly, he worked for Cardinal Health, a Fortune 16 company, where he was Vice President of Biotechnology Services. Dr. Price has also held senior-level management positions at BioReliance, where he was a key member of the team that led the company public in 1997, at Damon Biotech in the U.K. and Ortho Diagnostic Systems, a Johnson & Johnson Company. In addition, he co- founded the Institute for Cell Analysis at the University of Miami (FL), the International Center for Entrepreneurial Excellence at the University of Guadalajara, and Quality Biotech, a successful biosafety testing company. -

Marissa Silverman Curriculum Vitae Assistant Professor & Coordinator of Undergraduate Music Education John J

Marissa Silverman Curriculum Vitae Assistant Professor & Coordinator of Undergraduate Music Education John J. Cali School of Music Montclair State University 1 Normal Ave, Montclair, NJ 07043 Phone: (973) 655-7779 [email protected] Education 2004: Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Music Performance. New York University. Dissertation: How a Performer Makes Meaning in Music: An Analysis of Selected Interpretations by Pianist Gregory Haimovsky, Applying Louise M. Rosenblatt’s Reader Response Theory. Dissertation Chair: Professor Joy Boyum 2007: Master of Science for Teachers (M.S.T.) in Education. Pace University 1998: Master of Fine Arts (M.F.A.) in Music Performance (Flute). State University of New York, Purchase 1995: Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) in English and American Literature. New York University Publications Book Proposal Submitted Silverman, Marissa. Becoming a music educator: Action, reflection, and ethics. New York: Routledge. (250 pages). Submitted for review: September 25, 2010. Book Forthcoming Elliott, David J., & Silverman, Marissa. Music matters: A praxial philosophy of music education, 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press. Forthcoming in 2011. (360 pages). Contract available. Edited Book Forthcoming Veblen, Kari, Messenger, Steve, & Silverman, Marissa, Eds. Community Music Today. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Invited and Refereed Book Chapters in Edited Volumes. In Press. Contracts available. Silverman, Marissa. Why music matters: Philosophical and cultural foundations. In Raymond MacDonald, Gunter Kreutz, & Laura Mitchell (Eds.), Music, Health and Wellbeing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Silverman, Marissa. Community music and social justice: Re-claiming love. In Gary McPherson & Graham Welch (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Education. New York: Oxford University Press. Cohen, Mary, & Silverman, Marissa. -

1 8/2014 Curriculum Vitae HENRY A. DIETZ Department of Government

1 8/2014 Curriculum Vitae HENRY A. DIETZ Department of Government 4923 Strass Drive Batts 3.124 Austin TX 78731 University of Texas at Austin (512) 452-1252 Austin, Texas 78712 (512) 471-5121 department; 512-232-7209 office FAX: 512-471-1061 e-mail: [email protected] Date of Birth: November 23, 1941 Educational History B.A. (English), Miami University (Ohio), 1964 M.A. (Political Science), Indiana University, 1968 Ph.D. (Political Science), Stanford University, 1975 Employment History Instructor, University of Texas at Austin, 1972-1975 Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Austin, 1975-1979 Associate Professor, University of Texas at Austin, 1979-1997 Professor, University of Texas, 1997-present Visiting Scholar, Universidad del Pacifico (Lima, Peru), Centro de Investigaciones, January-August 1982 , summer 1985 Visiting Professor, United States Air Force Academy, 1985-1986. Visiting Scholar, Catholic University (Lima, Peru), summer 1990 Administrative Assignments University of Texas: International Exchange and Studies Committee, 1978-1980 Fulbright Selection Committee, 1978, 1979 (Chair), 1980 (Chair), 1981-1987 Benson Library Faculty Guidance Committee, 1983 University Educational Policy Committee, 1989-1990 Educational Policy Committee, 1988-1990 University Orientation Committee, 1989-1991 Associate Dean, College of Liberal Arts, 1993 Presidential Task Force on International Studies, 1994 Presidential Task Force on the establishment of a Center for Urban Studies, 1994 Member, Search Committee, director of Latin American Studies,