TREASURE ISLAND SQUIRE TRELAWNEY, Dr. Livesey, and the Rest of These Gentlemen Having Asked Me to Write Down the Whole Particula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery

TREASURE ISLAND BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ADAPTED BY BRYONY LAVERY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. TREASURE ISLAND Copyright © 2016, Bryony Lavery All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of TREASURE ISLAND is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for TREASURE ISLAND are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, England, W1F 0LE. -

Rurality, Class, Aspiration and the Emergence of the New Squirearchy

Rurality, Class, Aspiration and the Emergence of the New Squirearchy Jesse Heley Submission for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Geography & Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University 25th May 2008 For Ted, Sefton and the Wye Valley Contents 1 The coming of the New Squirearchy 1 1.1. The rebirth of rural Britain and the emergence of a New Squirearchy 2 1.2. Beyond the gravelled driveway 9 1.3. At play; beyond play? 15 1.4. From squirearchy to New Squirearchy; a reflection of changing class politics 25 1.5. Research goals 33 2 Class, identity and gentryfication 37 2.1. The New Squirearchy and the new middle class 37 2.2. A third way; through cultural capital to performing identity 43 2.3. Embodied rural geographies 48 2.4. Everyday performances and rural competencies 61 2.5. Tracking rural identity and accounting for experience 66 3 As I rode out … 75 3.1. Ethnography and rural geography 75 3.2. Eamesworth and the irony of a New Squirearchy 80 3.3. The coming of the commuter 84 3.4. On being a local lad 88 3.5. Gathering and interpreting evidence 91 3.6. The mechanics of data collection 94 3.7. The ethics of squire chasing 97 4 Out of the Alehouse 105 4.1. The pub, the squirearchy and the rural idyll 105 4.2. The Six Tuns 107 4.3. Office politics 110 4.4. Pass the port; the role of alcohol 113 4.5. Masculinity 115 4.6. New Squires; or archetypal middle class pub dwellers 119 4.7. -

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson adapted for the stage by Stewart Skelton Stewart E. Skelton 6720 Franklin Place, #404 Copyright 1996 Hollywood, CA 90028 213.461.8189 [email protected] SETTING: AN ATTIC A PARLOR AN INN A WATERFRONT THE DECK OF A SHIP AN ISLAND A STOCKADE ON THE ISLAND CAST: VOICE OF BILLY BONES VOICE OF BLACK DOG VOICE OF MRS. HAWKINS VOICE OF CAP'N FLINT VOICE OF JIM HAWKINS VOICE OF PEW JIM HAWKINS PIRATES JOHNNY ARCHIE PEW BLACK DOG DR. LIVESEY SQUIRE TRELAWNEY LONG JOHN SILVER MORGAN SAILORS MATE CAPTAIN SMOLLETT DICK ISRAEL HANDS LOOKOUT BEN GUNN TIME: LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY TREASURE ISLAND/Skelton 1 SCENE ONE (A treasure chest sits alone on plank flooring. We hear the creak of rigging on a ship set adrift. As the lights begin to dim, we hear menacing, thrilling music building in the background. When a single spot is left illuminating the chest, the music comes to a crashing climax and quickly subsides to continue playing in the background. With the musical climax, the lid of the chest opens with a horrifying groan. Light starts to emanate from the chest, and the spotlight dims. Voices and the sounds of action begin to issue forth from the chest. The music continues underneath.) VOICE OF BILLY BONES (singing) "Fifteen men on the dead man's chest - Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum! Drink and the devil had done for the rest - Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!" VOICE OF BLACK DOG Bill! Come, Bill, you know me; you know an old shipmate, Bill, surely. -

Four } Adoption in the Developing British Novel: Stigma, Social Protest, and Gender

Four } Adoption in the Developing British Novel: Stigma, Social Protest, and Gender In the survey of English literature that I took in my sophomore year of college, the only novel we read was Tom Jones. We never considered Tom as an adoptee. Ironically, the teacher of this course, Mrs. Giovan- nini, was known to be an adoptive mother. The course was not generally considered exciting. My roommate and then best friend recounted to me a conversation in which Mrs. Gio- vannini mentioned her daughter sleeping in class. “She’s her mother’s daughter,” my roommate joked. Embarrassed by her re›ex witticism, she said to me that “the awful thing is that she isn’t her mother’s daugh- ter.” I, who had told her I was adopted and was used to thinking of my adoptive mother as simply my mother, said nothing. How many children had Mrs. Giovannini? Was Tom Jones Squire Allworthy’s son or not? What was my friend saying about me? And whose daughter was I? Many historians and literary critics associate the rise of the nuclear fam- ily with the rise of the novel. Christopher Flint has even argued that the patterns of narrative “formally manifest” the social mechanisms of the family.1 But while Flint argues that there is af‹nity because “Both nar- rative and genealogy usually develop in linear fashion,” in many novels, including those to be discussed in this chapter, genealogy is much more puzzling and jagged than linear in its presentation.2 Disturbed genealo- gies and displaced children are common in the eighteenth- and nine- teenth-century British novel. -

Treasure Island

School Radio Treasure Island 6. The stockade and the pirates attack Narrator: On Treasure Island you might be forgiven for thinking a war was taking place. Anchored in the bay, the Hispaniola is firing her cannon deep into the woods. And through the trees, the pirates advance, muskets blazing. Oblivious to the danger, young Jim Hawkins races through the undergrowth heading for the Union Jack that flies bravely atop the trees. When he gets there, it’s a relief to find there’s shelter. A tall wooden stockade stands in a clearing - and inside it, his old friends Squire Trelawney, Doctor Livesey, Captain Smollett and a handful of faithful sailors, are fending off a full-blown attack from the pirates. Jim: Doctor! Squire! Captain! Let down the drawbridge! It’s me! Dr Livesey: Quickly, men, let the boy in! Squire: Jim - we thought we’d lost you! Hunter: Happen as still might unless we keep them muskets firing. Squire: Ah, yes, good thinking my man. Repel the blackguards! A sovereign for every man we put down! Narrator: But the pirates give up the fight - for now. Jim and the others exchange news. It turns out that the stockade they’re in was built many years ago by Captain Flint as a stronghold if ever he should be attacked. Squire Trelawney and the others just beat Silver and the pirates to it - though they lost a couple of good men in so doing. They managed to salvage enough guns, ammunition and food from the ship to keep them going for a couple of weeks but not much more. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’S Tale

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities English Department 2016 Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’s Tale Laurel Meister Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_expositor Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Repository Citation Meister, L. (2016). Freakish, feathery, and foreign: Language of otherness in the Squire's tale. The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities, 12, 48-57. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’s Tale Laurel Meister hough setting a standard for English literature in the centuries to follow, The Canterbury Tales was anything but standard in its Town time. Written in a Middle English vernacular that was only recently being used for poetry, and filtered through the minds and mouths of the wackiest of characters, Geoffrey Chaucer’s storytelling explores the Other: an unfamiliar realm set apart from the norm. One of the tales whose lan- guage engages with the Other, the Squire’s Tale features a magical ring al- lowing its wearer to understand any bird “And knowe his menyng openly and pleyn / and answere hym in his langage again,” a rhyme that repeats like an incantation throughout the tale.1 Told from the perspective of a young and inexperienced Squire, the story has all the makings of a chivalric fairy- tale—including a knight and a beautiful princess—with none of the finesse. -

Forgers and Fiction: How Forgery Developed the Novel, 1846-79

Forgers and Fiction: How Forgery Developed the Novel, 1846-79 Paul Ellis University College London Doctor of Philosophy UMI Number: U602586 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602586 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis argues that real-life forgery cases significantly shaped the form of Victorian fiction. Forgeries of bills of exchange, wills, parish registers or other documents were depicted in at least one hundred novels between 1846 and 1879. Many of these portrayals were inspired by celebrated real-life forgery cases. Forgeries are fictions, and Victorian fiction’s representations of forgery were often self- reflexive. Chapter one establishes the historical, legal and literary contexts for forgery in the Victorian period. Chapter two demonstrates how real-life forgers prompted Victorian fiction to explore its ambivalences about various conceptions of realist representation. Chapter three shows how real-life forgers enabled Victorian fiction to develop the genre of sensationalism. Chapter four investigates how real-life forgers influenced fiction’s questioning of its epistemological status in Victorian culture. -

Treasure Island

UNIT: TREASURE ISLAND ANCHOR TEXT UNIT FOCUS Students read a combination of literary and informational texts to answer the questions: What are different types of treasure? Who hunts for treasure and how? Why do people Great Illustrated Classics Treasure Island, Robert Louis search for treasure? Students also discuss their personal treasures. Students work to Stevenson understand what people are willing to do to get treasure and how different types of treasure have been found, lost, cursed, and stolen over time. RELATED TEXTS Text Use: Describe characters’ changing motivations in a story, read and apply nonfiction Literary Texts (Fiction) research to fictional stories, identify connections of ideas or events in a text • The Ballad of the Pirate Queens, Jane Yolen Reading: RL.3.1, RL.3.2, RL.3.3, RL.3.4, RL.3.5, RL.3.6, RL.3.7, RL.3.10, RI.3.1, RI.3.2, RI.3.3, • “The Curse of King Tut,” Spencer Kayden RI.3.4, RI.3.5, RI.3.6, RI.3.7, RI.3.8, RI.3.9, RI.3.10 • The Stolen Smile, J. Patrick Lewis Reading Foundational Skills: RF.3.3d, RF.3.4a-c • The Mona Lisa Caper, Rick Jacobson Writing: W.3.1a-d, W.3.2a-d, W.3.3a-d, W.3.4, W.3.5, W.3.7, W.3.8, W.3.10 Speaking and Listening: SL.3.1a-d, SL.3.2, SL.3.3, SL.3.4, SL.3.5, SL.3.6 Informational Texts (Nonfiction) • “Pirate Treasure!” from Magic Tree House Fact Language: L.3.1a-i; L.3.2a, c-g; L.3.3a-b; L.3.4a-b, d; L.3.5a-c; L.3.6 Tracker: Pirates, Will Osborne and Mary Pope CONTENTS Osborne • Finding the Titanic, Robert Ballard Page 155: Text Set and Unit Focus • “Missing Mona” from Scholastic • -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

Lesson 1 – What Is a Knight and How Were They Expected to Behave?

Lesson 1 – What is a knight and how were they expected to behave? What makes someone worthy of a knighthood? Send work to your teacher via Google Classroom, Google Drive or email. Activity 1 – Re-cap What qualities would you expect a knight to have? Activity 2 Read the information about knights given below and then answer the questions. The Medieval era was a time of constant war and fighting. Lords and their armies fought one another within their own countries for land and power and they also fought for their king against other countries. The most important person on these battlefields was the knights in their metal armour. Knights were warriors who fought on horseback for their king or their lord.Originally, knights could be men from lowly backgrounds, who were rewarded for their bravery or skill in battle. However, as time went on only men of noble birth were admitted to the knighthood and, even then, only after years of training in military service, serving others and Christian teachings. Figure 1 - a knight in metal armour on their horse who is First, a knight in training would wearing armour leave their family at the age of seven and become a Page. They would be taught to be polite, serve God, to ride and hunt, to understand the role of the knight and understand their code of chivalry. If, as a Page, they showed promise, then they would be selected to beccome a Squire at the Figure 3 - weapons a knight would have that a squire would look age of fourteen. -

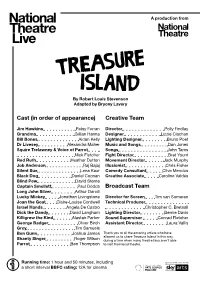

Cast (In Order of Appearance) Creative Team

A production from By Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery Cast (in order of appearance) Creative Team Jim Hawkins Patsy Ferran Director Polly Findlay Grandma Gillian Hanna Designer Lizzie Clachan Bill Bones Aidan Kelly Lighting Designer Bruno Poet Dr Livesey Alexandra Maher Music and Songs Dan Jones Squire Trelawney & Voice of Parrot Songs John Tams Nick Fletcher Fight Director Bret Yount Red Ruth Heather Dutton Movement Director Jack Murphy Job Anderson Raj Bajaj Illusionist Chris Fisher Silent Sue Lena Kaur Comedy Consultant Clive Mendus Black Dog Daniel Coonan Creative Associate Caroline Valdés Blind Pew David Sterne Captain Smollett Paul Dodds Broadcast Team Long John Silver Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey Jonathan Livingstone Director for Screen Tim van Someren Joan the Goat Claire-Louise Cordwell Technical Producer Israel Hands Angela De Castro Christopher C. Bretnall Dick the Dandy David Langham Lighting Director Bernie Davis Killigrew the Kind Alastair Parker Sound Supervisor Conrad Fletcher George Badger Oliver Birch Assistant Director Laura Vallis Grey Tim Samuels Ben Gunn Joshua James Thank you to all the amazing artists who have allowed us to share Treasure Island in this way, Shanty Singer Roger Wilson during a time when many theatre fans aren’t able Parrot Ben Thompson to visit their local theatre. Running time: 1 hour and 50 minutes, including a short interval BBFC rating: 12A for cinema Help Jim Hawkins find the buried gold! Can you trace your way from the ship to X marks the spot and the treasure? Image: Freepik.com Image: Did you know? Excerpts from Treasure Island show programme articles by Andrew Lambert, David Cordingly and Tristan Gooley.