James Buchanan, the Squire from Lancaster 15 Sketching the Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rurality, Class, Aspiration and the Emergence of the New Squirearchy

Rurality, Class, Aspiration and the Emergence of the New Squirearchy Jesse Heley Submission for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Geography & Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University 25th May 2008 For Ted, Sefton and the Wye Valley Contents 1 The coming of the New Squirearchy 1 1.1. The rebirth of rural Britain and the emergence of a New Squirearchy 2 1.2. Beyond the gravelled driveway 9 1.3. At play; beyond play? 15 1.4. From squirearchy to New Squirearchy; a reflection of changing class politics 25 1.5. Research goals 33 2 Class, identity and gentryfication 37 2.1. The New Squirearchy and the new middle class 37 2.2. A third way; through cultural capital to performing identity 43 2.3. Embodied rural geographies 48 2.4. Everyday performances and rural competencies 61 2.5. Tracking rural identity and accounting for experience 66 3 As I rode out … 75 3.1. Ethnography and rural geography 75 3.2. Eamesworth and the irony of a New Squirearchy 80 3.3. The coming of the commuter 84 3.4. On being a local lad 88 3.5. Gathering and interpreting evidence 91 3.6. The mechanics of data collection 94 3.7. The ethics of squire chasing 97 4 Out of the Alehouse 105 4.1. The pub, the squirearchy and the rural idyll 105 4.2. The Six Tuns 107 4.3. Office politics 110 4.4. Pass the port; the role of alcohol 113 4.5. Masculinity 115 4.6. New Squires; or archetypal middle class pub dwellers 119 4.7. -

Four } Adoption in the Developing British Novel: Stigma, Social Protest, and Gender

Four } Adoption in the Developing British Novel: Stigma, Social Protest, and Gender In the survey of English literature that I took in my sophomore year of college, the only novel we read was Tom Jones. We never considered Tom as an adoptee. Ironically, the teacher of this course, Mrs. Giovan- nini, was known to be an adoptive mother. The course was not generally considered exciting. My roommate and then best friend recounted to me a conversation in which Mrs. Gio- vannini mentioned her daughter sleeping in class. “She’s her mother’s daughter,” my roommate joked. Embarrassed by her re›ex witticism, she said to me that “the awful thing is that she isn’t her mother’s daugh- ter.” I, who had told her I was adopted and was used to thinking of my adoptive mother as simply my mother, said nothing. How many children had Mrs. Giovannini? Was Tom Jones Squire Allworthy’s son or not? What was my friend saying about me? And whose daughter was I? Many historians and literary critics associate the rise of the nuclear fam- ily with the rise of the novel. Christopher Flint has even argued that the patterns of narrative “formally manifest” the social mechanisms of the family.1 But while Flint argues that there is af‹nity because “Both nar- rative and genealogy usually develop in linear fashion,” in many novels, including those to be discussed in this chapter, genealogy is much more puzzling and jagged than linear in its presentation.2 Disturbed genealo- gies and displaced children are common in the eighteenth- and nine- teenth-century British novel. -

Black Beauty

Black Beauty Black Beauty The story Black Beauty was a handsome horse with one white foot and a white star on his forehead. His life started out on a farm with his mother, Duchess, who taught him to be gentle and kind and to never bite or kick. When Black Beauty was four years old, he was sold to Squire Gordon of Birtwick Park. He went to live in a stable where he met and became friends with two horses, Merrylegs and Ginger. Ginger started life with a cruel owner who used a whip on her. She treated her cruel owner with the lack of respect he deserved. When she went to live at Birtwick Park, Ginger still kicked and bit, but she grew happier there. The groom at Birtwick Park, John, was very kind and never used a whip. Black Beauty saved the lives of Squire Gordon and John one stormy night when they tried to get him to cross a broken bridge. The Squire was very grateful and loved Black Beauty very much. One night a foolish young stableman left his pipe burning in the hay loft where Black Beauty and Ginger were staying. Squire Gordon’s young stableboy, James, saved Black Beauty and Ginger from the burning stable. The Squire and his wife were very grateful and proud of their young stableboy. James got a new job and left Birtwick Park and a new stableboy, Joe Green, took over. Then, one night Black Beauty nearly died because of Joe’s lack of experience and knowledge. The Gordons had to leave the country because of Mrs Gordon’s health and sold Black Beauty to Lord Westerleigh at Earlshall Park. -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Cham : the Best Comic Strips and Graphic Novelettes, 1839-1862 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHAM : THE BEST COMIC STRIPS AND GRAPHIC NOVELETTES, 1839-1862 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Kunzle | 538 pages | 30 May 2019 | University Press of Mississippi | 9781496816184 | English | Jackson, United States Cham : The Best Comic Strips and Graphic Novelettes, 1839-1862 PDF Book A chapter on fashionable ball dress is also included. Recensioner i media. DC, As mentioned in the description, this Sanjulian book was a Kickstarter project. He is one much deserving, at last, of this first account of his huge oeuvre as a caricaturist. Because the process took so long, the voting window for comic book professionals is shorter, but the awards are still going to be given out in July. Halfway the serialisation the originals were clumsily redrawn by a staff member possibly Cham? L'Exposition de Londres by Cham Book 12 editions published between and in French and held by 43 WorldCat member libraries worldwide. During his lifetime he was one of the most popular French cartoonists. Rows: Columns:. The tall man holding a woman with an umbrella's hand is a self-caricature. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for: Beware, you are proposing to add brand new pages to the wiki along with your edits. Yet beneath the surface, tensions linger sixteen years after a failed rebellion. Presenting the history of corsetry and body sculpture, this edition shows how the relationship between fashion and sex is closely bound up with sexual self-expression. In several scenes Cham introduces concepts like close-ups, wide shots, jumpcuts and different perspectives. Since his back catalogue is so immense, few art historians have taken time to explore and study his work in its entirety. -

Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’S Tale

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities English Department 2016 Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’s Tale Laurel Meister Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_expositor Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Repository Citation Meister, L. (2016). Freakish, feathery, and foreign: Language of otherness in the Squire's tale. The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities, 12, 48-57. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’s Tale Laurel Meister hough setting a standard for English literature in the centuries to follow, The Canterbury Tales was anything but standard in its Town time. Written in a Middle English vernacular that was only recently being used for poetry, and filtered through the minds and mouths of the wackiest of characters, Geoffrey Chaucer’s storytelling explores the Other: an unfamiliar realm set apart from the norm. One of the tales whose lan- guage engages with the Other, the Squire’s Tale features a magical ring al- lowing its wearer to understand any bird “And knowe his menyng openly and pleyn / and answere hym in his langage again,” a rhyme that repeats like an incantation throughout the tale.1 Told from the perspective of a young and inexperienced Squire, the story has all the makings of a chivalric fairy- tale—including a knight and a beautiful princess—with none of the finesse. -

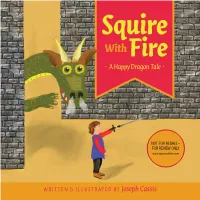

NOT for RESALE - for REVIEW ONLY Squire with Fire · a Happy Dragon Tale ·

NOT FOR RESALE - FOR REVIEW ONLY www.squirewithfire.com Squire With Fire · A Happy Dragon Tale · WRITTEN & ILLUSTRATED BY Joseph Cassis “Grandpa, what is that?” Mac asked as the curious young child pointed to Grandfather’s wrinkled but strong hand. 1 “You mean this gold ring?” responded Grandpa, who was dressed in his favorite royal purple shirt. He proudly curled his hand into a tight fist to show Mac his gold ring better. Mac nodded. “Yep, it’s so shiny.” Grandpa leaned into Mac and said in a soft voice, “My father gave it to me and his father gave it to him and his grandfather gave it to him. Well, you get the idea. It was a very long time ago. This special family ring is over 600 years old.” Mac’s big brown eyes widened, staring at the “Well, it’s just not that easy, Mac. You must gleaming ring. “Wow, like you, Grandpa?” show me that you have all the qualities of a squire,” said Grandpa. Grandpa chuckled. “Well, no. I am a bit younger than 600. When they were seven years old, Mac looked puzzled and stared at Grandpa. “A our ancestors competed to be squires. They squire? What’s a squire?” learned the ways of being a knight, and then Grandpa answered with a slight grin, “A squire is if they proved they were worthy, they became young person who is a knight’s helper.” squires at fourteen and received this beautiful gold ring.” Mac smiled. “I know. You mean he helps knights fight dragons?” “Oh,” Mac said, excitedly. -

Forgers and Fiction: How Forgery Developed the Novel, 1846-79

Forgers and Fiction: How Forgery Developed the Novel, 1846-79 Paul Ellis University College London Doctor of Philosophy UMI Number: U602586 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602586 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis argues that real-life forgery cases significantly shaped the form of Victorian fiction. Forgeries of bills of exchange, wills, parish registers or other documents were depicted in at least one hundred novels between 1846 and 1879. Many of these portrayals were inspired by celebrated real-life forgery cases. Forgeries are fictions, and Victorian fiction’s representations of forgery were often self- reflexive. Chapter one establishes the historical, legal and literary contexts for forgery in the Victorian period. Chapter two demonstrates how real-life forgers prompted Victorian fiction to explore its ambivalences about various conceptions of realist representation. Chapter three shows how real-life forgers enabled Victorian fiction to develop the genre of sensationalism. Chapter four investigates how real-life forgers influenced fiction’s questioning of its epistemological status in Victorian culture. -

Lesson 1 – What Is a Knight and How Were They Expected to Behave?

Lesson 1 – What is a knight and how were they expected to behave? What makes someone worthy of a knighthood? Send work to your teacher via Google Classroom, Google Drive or email. Activity 1 – Re-cap What qualities would you expect a knight to have? Activity 2 Read the information about knights given below and then answer the questions. The Medieval era was a time of constant war and fighting. Lords and their armies fought one another within their own countries for land and power and they also fought for their king against other countries. The most important person on these battlefields was the knights in their metal armour. Knights were warriors who fought on horseback for their king or their lord.Originally, knights could be men from lowly backgrounds, who were rewarded for their bravery or skill in battle. However, as time went on only men of noble birth were admitted to the knighthood and, even then, only after years of training in military service, serving others and Christian teachings. Figure 1 - a knight in metal armour on their horse who is First, a knight in training would wearing armour leave their family at the age of seven and become a Page. They would be taught to be polite, serve God, to ride and hunt, to understand the role of the knight and understand their code of chivalry. If, as a Page, they showed promise, then they would be selected to beccome a Squire at the Figure 3 - weapons a knight would have that a squire would look age of fourteen. -

BARSTOW, Robert Squire, 1936- the THEATRE MUSIC of DANIEL PURCELL

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 6 9 -4 8 4 2 BARSTOW, Robert Squire, 1936- THE THEATRE MUSIC OF DANIEL PURCELL. (VOLUMES I AND II). The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Robert Squire Barstow 1969 - THE THEATRE MUSIC OF DANIEL PURCELL .DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for_ the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Squire Barstow, B.M., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Department of Music ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To the Graduate School of the Ohio State University and to the Center of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, whose generous grants made possible the procuring of materials necessary for this study, the author expresses his sincere thanks. Acknowledgment and thanks are also given to Dr. Keith Mixter and to Dr. Mark Walker for their timely criticisms in the final stages of this paper. It is to my adviser Dr. Norman Phelps, however, that I am most deeply indebted. I shall always be grateful for his discerning guidance and for the countless hours he gave to my problems. Words cannot adequately express the profound gratitude I owe to Dr. C. Thomas Barr and to my wife. Robert S. Barstow July 1968 1 1 VITA September 5, 1936 Born - Gt. Bend, Kansas 1958 .......... B.M. , ’Port Hays Kansas State College, Hays, Kansas 1958-1961 .... Instructor, Goodland Public Schools, Goodland, Kansas 1961-1964 .... National Defense Graduate Fellow, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1963............ M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio __ 1964-1966 ... -

Superhero Origins As a Sentence Punctuation Exercise

Superhero Origins as a Sentence Punctuation Exercise The Definition of a Comic Book Superhero A comic book super hero is a costumed fictional character having superhuman/extraordinary skills and has great concern for right over wrong. He or she lives in the present and acts to benefit all mankind over the forces of evil. Some examples of comic book superheroes include: Superman, Batman, Spiderman, Wonder Woman, and Plastic Man. Each has a characteristic costume which distinguishes them from everyday citizens. Likewise, all consistently exercise superhuman abilities for the safety and protection of society against the forces of evil. They ply their gifts in the present-contemporary environment in which they exist. The Sentence Punctuation Assignment From earliest childhood to old age, the comics have influenced reading. Whether the Sunday comic strips or editions of Disney’s works, comic book art and narratives have been a reading catalyst. Indeed, they have played a huge role in entertaining people of all ages. However, their vocabulary, sentence structure, and overall appropriateness as a reading resource is often in doubt. Though at times too “graphic” for youth or too “childish” for adults, their use as an educational resource has merit. Such is the case with the following exercise. Superheroes as a sentence punctuation learning toll. Among the most popular of comic book heroes is Superman. His origin and super-human feats have thrilled comic book readers, theater goers, and television watchers for decades. However, many other comic book superheroes exist. Select one from those superhero origin accounts which follow and compose a four paragraph superhero origin one page double-spaced narative of your selection.