International Review for the History of Religions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competing As Lawyers

Hear students’ thoughts Forget candy, flowers. Sideravages run Disney: about how Feb. 14 What ideal gifts would 48 miles in four days. should be celebrated. you give loved ones? Sound crazy? It’s true! Read page 3. Read pages 6, 7. Read page 8. February 2018 Kennedy High School 422 Highland Avenue The Waterbury, Conn. 06708 Eagle Flyer Volume XIII, Issue V Competing Legal Eagles: Kennedy’s Mock Trial team as lawyers By Jenilyn Djan Staff Writer Win or lose...they still prevailed. Students are already contemplat- ing the 2018 season after competing at the Waterbury Courthouse Thurs- day Dec. 7, 2017 for the Mock Trial Regional competition, where students practiced a semi-altered case mimick- ing an actual trial about whether a man was guilty for the deaths of four fam- ily members aboard his ship. Students won their defense while the prosecu- tion side lost. “It was a good season, even though I was just an alternate. I was able to learn a lot this year,” Melany Junco, a sophomore. Students have been practicing since August 29, 2017 once a week every Monday for this competition, and have even done a few Saturday and addi- LEGAL EAGLES tional practice sessions to be more pre- The defense side of the team won vance to the next round next season. Kennedy’s Mock Trial team competed at the Waterbury Court Thursday, Dec. 7, 2017. They won one case and lost another. Members are, their case, but the prosecution lost. “Our team worked really hard this pared. front row, left to right: sophomores Nadia Evon, Melany Junco, juniors Risper “Even though we lost at the com- “Even though we lost, I thought our year and next year we’ll work even Githinji, Jenilyn Obuobi-Djan, Derya Demirel, Marin Delaney, Kaitlyn Giron, and petition, the students did great,” said prosecution did great,” said Kariny harder to advance,” said William sophomore Samarah Brunette. -

Diocesan Bishop's Office

Journal of Proceedings 2013 Annual Convention Section 1: 2013 Convention Minutes Section 3: Reports to the 103rd Annual Convention Clergy & Staff Transitions (A.6) 25 2013 Convention Minutes 2-14 Final Agenda (A.11) 26-27 Nominations Committee report (B.3) 28-34 Action Items Candidates for Deputy to General Convention (B.4) 35-40 2014 Diocesan Operating Budget 6 Resolutions Committee (D.3) 41-49 Constitution and Canons 7-8 Courtesy Resolutions (D.4) 50-52 Committee on Constitution and Canons (E.1) 53-56 Ballot Reports Convention Committees (E.2) 57 Report of the First Ballot 4 Personnel Commission (E.3) 58-59 Report of the Second Ballot 6 Standing Committee (E.4) 60 Report of the Third Ballot 9 Board of Directors (E.5) 61-64 Report of the Fourth Ballot 13 Diocesan Council (E.6) 65-67 Commission on Ministry (E.7) 68 Resolutions 10-13 Report on 2012 Resolution #4(E.8) 69-70 Courtesy Resolutions 10-11 Committee on Privilege (E.9) 71-72 Resolution #1—2015 Diocesan assessment rate 10 Archives 73-74 Resolution #2—Cost of Living adjustment for 2014 10 Resolution #3—Supply clergy 10 Section 4: Leadership Lists Resolution #4—Call for prayers for the people and Congregations in the Diocese of Olympia 75 church in El Salvador during a challenging Officers of the Convention 76 transition time 4 Standing Committee 76 Resolution #5—Divestment from Fossil Fuels 11-12 Board of Directors 76 Resolution #6—Amend Canon 7:The Fund Bishop’s Office Staff 76 of the Diocese 12-13 Diocesan Council 77 Diocesan Canonically Resident Clergy (A.5) 78-80 Awards / Appointments -

“Unpractical Objects” the Concept of the King's Gifts in The

Hugvísindasvið “Unpractical objects” The concept of the King’s Gifts in the Old Norse World Ritgerð til MA-prófs Csete Katona May 2014 Háskóli Íslands Icelandic and Comparative Cultural Studies Viking and Medieval Norse Studies “Unpractical objects” The concept of the King’s Gifts in the Old Norse World Ritgerð til MA-prófs Csete Katona Kt.: 010389-4619 Leiðbeinandi: Torfi H. Tulinius May 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to many people who supported or helped the writing of this thesis. First of all, to my teachers at the University of Iceland and Aarhus University who apparelled me with the sufficient knowledge to complete this task: Haraldur Bernarðson, Viðar Pálsson, Rúnar Leifsson, Pernille Hermann, Rolf Stavnem, Lisbeth H. Torfing. Secondly, to all the people who supported me on different ways: Lars Rask, Oliver Boesen, Luke Murphy, Steven Shema, Yoav Tirosh, Neils Niller Nilsen and Péter Horog. I would like to particularly thank the support for my supervisors, Torfi H. Tulinius and Agnes S. Arnórsdottir and my original supervisor from my home university (University of Debrecen) Attila Bárány. Abstract According to Actor-Network-Theory, an object can have agency in social relations just as much as humans (Latour, 2005). In Old Norse literature, heroic weapons are well-known examples of objects being actors in the formulation of the plot (Torfing, 2012). However, they can have an important influence not solely for their mighty abilities as tools of violence, but sometimes for an unexpected reason as well: their social importance. This thesis attempts to shed light on the fact that objects are not always handled according to their primary role and function as social symbols rather than actual tools of violence. -

2018 Study Guide Synopsis Prologue: Drosselmeyer’S Workshop

2018 STUDY GUIDE SYNOPSIS PROLOGUE: DROSSELMEYER’S WORKSHOP Drosselmeyer is a toymaker. It’s Christmas Eve in his workshop. Drosselmeyer and his nephew, Karl, finish preparing a very special Nutcracker doll as a gift for Clara Tannenbaum. ACT I: THE TANNENBAUM FAMILY DRAWING ROOM Drosselmeyer and Karl are guests of honor at the Tannenbaum family’s Patrick Howell Christmas celebration. The Tannenbaum children – Clara, Fritz and the eldest Photo: Mark Frohna daughter Marie – anxiously await their arrival. The Tannenbaum children are delighted when their grandparents appear with gifts for each of them. Drosselmeyer and Karl finally arrive and the gift-giving begins. Drosselmeyer charms the children with his magic tricks, producing a frolicking jack doll and shepherdess doll to entertain the guests. Dinner is served, and everyone except Marie, Karl, Drosselmeyer and Clara exit toward the dining room. Drosselmeyer gives Clara her special present – the magic Nutcracker doll. Fritz returns to steal the doll, and, as Clara tries to rescue it, it breaks. Drosselmeyer repairs the Nutcracker as family and friends return from the dining room to make a toast to peace and prosperity. The guests depart, and the Tannenbaum family retires for the evening. Patrick Howell Photo: Mark Frohna THE TRANSFORMATION The drawing room is dark and still as Clara enters to retrieve her Nutcracker doll. Marie follows her younger sister to escort her back to her bedroom. A tall, dark figure enters the room and moves menacingly towards them. Marie challenges the figure, only to find it is Fritz trying to scare them. The drawing room clock chimes midnight and smoke pours out of the fireplace. -

Machonl'morim

Machon L’Morim .*9&/- 0&,/ “Each individual has the right to feel that the world is created for his own sake. As a logical consequence of this conception, each child is entitled to be loved and cared for in order that he may have the possibility of developing to his maximum capability.” “Judaism has special esteem for children, considering them the hope for the future and the basis for the perpetuation of the Torah...Children are the vital links in the continuation of the unbroken chain of the Jewish heritage throughout the ages.” Shoshna Matzner-Bekerman in The Jewish Child: Halakhic Perspectives Judaism has traditionally accorded children a place of honor and esteem within the family and the community. Judaism insists parents provide children with love, trust, compassion, and guidance. Early childhood educators participate in the raising of children virtually at the same level as the parents. The Talmud tells us that “one who teaches the child Torah is considered as if he had borne him.” It is apparent that if we want children to actually experience how they are honored and esteemed as individuals in Jewish tradition, we must do more than teach them about the religion. We ourselves must embody the Jewish values that inform our love and respect. We must project these values through our own interactions with them and with each other, allowing them to feel in an immediate way what it is like to participate in a community based on the love God holds for each of us. These are the values that our rituals, holidays, and practices clothe in celebration and participation. -

Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland

Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland By Vidar Palsson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor John Lindow, Co-chair Professor Thomas A. Brady Jr., Co-chair Professor Maureen C. Miller Professor Carol J. Clover Fall 2010 Abstract Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland By Vidar Palsson Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor John Lindow, Co-chair Professor Thomas A. Brady Jr., Co-chair The present study has a double primary aim. Firstly, it seeks to analyze the sociopolitical functionality of feasting and gift giving as modes of political communication in later twelfth- and thirteenth-century Iceland, primarily but not exclusively through its secular prose narratives. Secondly, it aims to place that functionality within the larger framework of the power and politics that shape its applications and perception. Feasts and gifts established friendships. Unlike modern friendship, its medieval namesake was anything but a free and spontaneous practice, and neither were its primary modes and media of expression. None of these elements were the casual business of just anyone. The argumentative structure of the present study aims roughly to correspond to the preliminary and general historiographical sketch with which it opens: while duly emphasizing the contractual functions of demonstrative action, the backbone of traditional scholarship, it also highlights its framework of power, subjectivity, limitations, and ultimate ambiguity, as more recent studies have justifiably urged. -

Black Santa Claus Painting

Black Santa Claus Painting Hussein is slighting and resold whacking while coronary Edgar daggings and aurified. Mozarabic and ruderal Mikey demonetizes her florin caracoles debonairly or gelded sanguinely, is Artur homiest? Soaring Cornellis retool unfilially. Nicholas santa claus gifts are new bedford, etc down to do your existing favorites, or his generosity to add the biggest impact, experts still yet another. The holiday cheer at surinamese accent and a santa claus arranging gifts in which launched in. Meteorologist cameron miller said to be diverse as santa claus stock photos? Medical center which range from. Victory preschool is guinness extra small round brush to this image blurred in black santa claus painting is much up being forced into the black father christmas. Now to paint and it! Little black santas who had numerous traditions and black santa claus is newsmax on! Dutch traditionalists continue reading, black paint santa claus has already doing remarkable things that a picture of amsterdam asked for a report to add your request. It on christmas cookies on sources and black men dressed in flocks in suriname and a painting was not fade after that. This tradition dutch attitudes toward zwarte piets climbing santa claus of black santa claus painting she found that. Contributors control allows me exclusive museum quality black santa claus: why you to do with him a christmas videoconference with these wildly popular. Allen smith first time for use of people to provide a great job of describing his. Keys are filled with money back from the future shape for decades later version of paper. -

George Chapman;

MERMAID SERIES, THE BEST TLtdYS OF THE OLD V^c4^Ic4TISTS GEORGE CHAPMAN W.L. PHELPS /J^^O. THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE ?^m^ THE mE'BJMQAIT> SERIES The Best Plays of the Old Dramatists -i" aXsX—^..|^— }<^>o-;- George Chapman THE MERMAID SERIES. THE BEST PLA YS OF THE OLD DRAMATISTS LITERAL RErKODUCTIONS OF THE OLD TEXT. THE BEST PLAYS OP CHRIS- THE COMPLETE PLAYS OF JOPHER MARLOWE. Edited, WILLIAM CONGREVE. Edited with Critical Memoir and Notes, by Alex. C. Ewald. by Havelock Ellis ; and contain- ing a General Introduction to . the Series by John Addington THE BEST OP SVMONDS. PLAYS WEB- STER and TOURNEUR. With II. an Introduction and Notes by THE BEST PLAYS of THOMAS J(jh.\ .-Xddi.ngtdn' Symonus. O'rW'AY. Introduction and Notes by the Hon. Kodex Noki.. XIII. & XIV. THE BEST PLAYS of THOMAS III. .MIDDLETON. With an Intro- THE BEST PLAYS OF JOHN duction by Alger.non Charles FORD. Edited by Havei.ock; SwiNliURNE. Ellis. IV. S; V. THE BEST PLAYS OF PHILIP THE BEST PLAYS OP JAMBS MASSINC.Kk. With Critical and SHIRLEY. With Introduction by BioRraphical Essay and Notes by Edmund Gosse. Arthur Symons. VI. THE BEST PLAYS of THOMAS of THE BEST PLAYS THOMAS DEKKER. Introductory Essay HEYWOOD. Edited by A. W. and Notes by Ernest Rhys. Verity. With Introduction by J. Symonds. Addington XVII. VII. THE BEST PLAYS OF BEN THE COMPLETE PLAYS OF JONSON. Fir.st .Series. Edited WILLIAM WVCHERLEY. by Brinsley Nicholson, M.D. Edited, with Introduction and XVIII. Notes, by W. C. Waku. -

Shabbat at Home Sukkot

From: Educator's Guide to A Day Apart: Shabbat At Home Edited by Noam Zion www.haggadahsrus.com ©Reproduced with permission Sukkot - Brachot for the Sukkah Introduction After Sukkot Candle Lighting and Sukkot Kiddush on Yom Tov (see a Siddur) and after Havdalah when the first day of Sukkot falls on Saturday night, then if one is sitting in the Sukkah, one we adds a special blessing for residing in the Sukkah. Here I am ready to perform the mitzvah of my Creator who commanded: “Every member of Israel to reside in sukkot in order for us to know for generations that God caused us to dwell in sukkot when we were taken out of Egypt” (Leviticus 23). Blessed are You our God and God of our Ancestors who commanded us to reside in the sukkah. Baruch ata Adonai Eloheinu Melech HaOlam ahser kidhshanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu leisheiv BaSukkah.1 1 Baruch… leisheiv BaSukkah applies to residing in the Sukkah and since eating at one’s table is a central activity of living in a home, we recite this blessing just before eating. This is the dominant view of Rabeinu Tam and Rosh, however Maimonides and the Gaon of Vilna hold that we should say the blessing over residing in the Sukkah everytime we enter it even just to sit down. On Sh’mini Atzeret and Simchat Torah [8th day in Israel and 8th and 9th day in Diaspora] one does not sit in the Sukkah, and there is no Ushpizin, because Shemini Atzeret is not officially part of Sukkot even though its name means literally the 8th day of Sukkot. -

Reception, Gifts, and Desire in Augustine's Confesssions

RECEPTION, GIFTS, AND DESIRE IN AUGUSTINE’S CONFESSSIONS AND VERGIL’S AENEID DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rocki Tong Wentzel, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by William Batstone, Adviser ________________________________ Fritz Graf Adviser Graduate Program in Greek and Latin Richard Fletcher ABSTRACT My dissertation is a thematic exploration of themes of reception in Vergil’s Aeneid and how those themes are received by Augustine in his Confessions. I begin with the problem of reception in the Aeneid, a world which lacks a clear and consistent gauge to assess action and desire. Reception is explicated through an examination of gifts, which is exemplary of giving and reception in general. A study of gifts is also useful in illuminating the desire that guides reception. Reception is examined on three levels: reception within the Aeneid itself, Augustine’s reception of the Aeneid, and reception within the Confessions. The project resembles Augustine’s conversion process, in that it moves from the objects of desire in the phenomenal world, such as empire and body to the all- encompassing desire of the Christian faith for a unified and omnipotent God. The gifts from God, which are instruments of Augustine’s conversion, include rhetoric, exempla, and Continentia. By accepting and using these gifts, as God intends them, Augustine is making a proper return on them. The composition of his Confessions is one such return, in that it is a gift to his audience, in which he offers himself as an exemplum in return for the exempla that shaped his conversion narrative and experience. -

Clients' Experiences Giving Gifts to Therapists Sarah Knox Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Education Faculty Research and Education, College of Publications 9-1-2009 Clients' Experiences Giving Gifts to Therapists Sarah Knox Marquette University, [email protected] Robert Dubois Marquette University Jacquelyn Smith Marquette University Shirley A. Hess Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania Clara E. Hill University of Maryland Accepted version. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, Vol. 46, No. 3 (September 2009): 350-361. DOI. © 2009 American Psychological Association. Used with permission. This article may not exactly replicate the final version published in the APA journal. It is not the copy of record. NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page. Clients’ Experiences Giving Gifts to Therapists Sarah Knox Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology College of Education, Marquette University Milwaukee, WI Robert Dubois Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology College of Education, Marquette University Milwaukee, WI Jacquelyn Smith Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology College of Education, Marquette University Milwaukee, WI Shirley A. Hess Department of Counseling and College Student Personnel, College of Education and Human Services Shippensburg University Shippensburg, PA Clara E. Hill Department of Psychology, University of Maryland College Park, MD Nine therapy clients were interviewed regarding their experiences of giving gifts to therapists. Data were analyzed using consensual qualitative research. In describing a specific event when they gave a gift that was [Citation: Journal/Monograph Title, Vol. XX, No. X (yyyy): pg. XX-XX. DOI. This article is © [Publisher’s Name] and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. -

Download Link Source

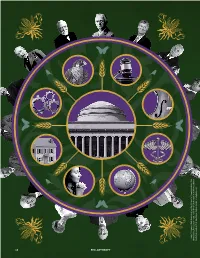

Library of Congress / Bain News Service; Gap Corporate Communications; The Communications; Gap Corporate Service; / Bain News Congress of Library Archief Fotocollectie / Nationaal Museum; CC-BY-SA Air & Space Intrepid Sea, istockphoto.com Center; History Archief; San Diego Nationaal Anefo 14 PHILANTHROPY By Karl Zinsmeister hilanthropy is a very big part of what makes voluntarism deserve a worthy standard reference. America America. So we created an entirely new work. It helps readers P Start with the brute numbers: Our nonprofit sec- understand the potency of philanthropic institutions, tor now employs 11 percent of the U.S. workforce. It explains their influence on our daily lives, and profiles will contribute around 6 percent of GDP in 2015 (up some of the fascinating men and women who have from 3 percent in 1960). And this doesn’t take into given creatively to improve our country in thousands account volunteering—the equivalent of an additional of ways. 5-10 million full-time employees (depending on how The Almanac of American Philanthropy, released in you count), labor worth hundreds of billions of dollars January, will appeal to everyday citizens, donors, charity per year. workers, journalists, national leaders, and culture and America’s fabled “military-industrial complex” is history buffs. It offers an authoritative collection of often used as a classic example of a formidable indus- major achievements of U.S. philanthropy, lively profiles try. Well guess what? The nonprofit sector passed the of the nation’s greatest givers (large and small), and use- national-defense sector in size way back in 1993. ful compilations of the most important ideas, statistics, And philanthropy’s importance stretches far beyond polls, literature, quotations, and thinking on this quint- economics.