The Original Series, Star Trek: the Next Generation, and Star Trek: Discovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

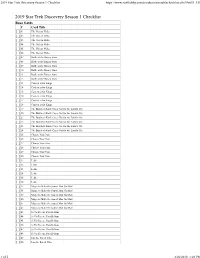

2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist

2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist https://www.scifihobby.com/products/printablechecklist.cfm?SetID=355 2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 02 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 03 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 04 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 05 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 06 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 07 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 08 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 09 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 10 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 11 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 12 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 13 Context is for Kings [ ] 14 Context is for Kings [ ] 15 Context is for Kings [ ] 16 Context is for Kings [ ] 17 Context is for Kings [ ] 18 Context is for Kings [ ] 19 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 20 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 21 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 22 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 23 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 24 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 25 Choose Your Pain [ ] 26 Choose Your Pain [ ] 27 Choose Your Pain [ ] 28 Choose Your Pain [ ] 29 Choose Your Pain [ ] 30 Choose Your Pain [ ] 31 Lethe [ ] 32 Lethe [ ] 33 Lethe [ ] 34 Lethe [ ] 35 Lethe [ ] 36 Lethe [ ] 37 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 38 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 39 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 40 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 41 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 42 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 43 Si Vis Pacem, Para Bellum [ ] 44 Si Vis Pacem, -

Trekkies Beware! Paramount Pictures V. Axanar Productions by Joel M

Thursday, March 23, 2017 LAW BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY LAW TECHNOLOGY LAW BUSINESS RECORDERdaily at www.therecorder.com Trekkies Beware! Paramount Pictures v. Axanar Productions By Joel M. Grossman ovie and far and actually produce a very TV stu- professional movie funded by dios often crowdsourcing? That is the allow their question raised by the case of fans to Paramount Pictures Corp. v. Mengage in behavior which tech- Axanar Productions, Inc. The nically might violate copyright case has not been fully liti- or trademark law. For exam- gated, but the district court’s ple, the studio which owns the ruling on cross-motions for copyright to Star Wars might summary judgment is both let fans produce a short video amusing and instructive. in which fans dress up as Darth To begin with the basic facts, Vader or Princess Leia, and act plaintiff Paramount Pictures Trek films before with no law- out a scene from the film. If and CBS own the copyright to suit from Paramount, Axanar the fans post their homemade the Star Trek television shows sought to go “where no man 10 minute video on You Tube, and Paramount owns the copy- has gone before” and produce the studio probably wouldn’t right to the thirteen full-length a professional Star Trek film, mind. They might even encour- movies that followed. While with a fully professional crew, age such amateur tributes, as the copyright owners allowed many of whom worked on one they might keep interest in the fans to make their own ama- or more Star Trek productions. -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

Star Trek: Exploring New Worlds Is a Fully Immersive Exhibition That Showcases Star Trek’S Significant Impact on Culture, Society, Arts, Sports, Tech and Fashion

STAR TREK: EXPLORING NEW WORLDS IS A FULLY IMMERSIVE EXHIBITION THAT SHOWCASES STAR TREK’S SIGNIFICANT IMPACT ON CULTURE, SOCIETY, ARTS, SPORTS, TECH AND FASHION. VENUE: SECURITY: AVAILABILITY: ORGANIZATION 5,000–7,000K SF Medium October April rental period of 2019 2020 & CONTACT 12–14 weeks SPECIAL Shawana Lee REQUIREMENTS Group Sales Manager FEE: ADDITIONAL 206 262 3420 Min. ceiling height of $250,000 plus 14 feet, climate control, shipping & RESOURCES [email protected] gallery supervision, installer’s travel Marketing & promo standard electrical sup- Museum of POP Culture costs templates provided ply, traveling installer (formerly EMP Museum) expenses: (est. $8K) EXHIBIT HIGHLIGHTS Set pieces Transporter simulator EXHIBITION ELEMENTS from Star Trek: The Original Series, where visitors can create a film that including a self destruct panel and shows them being beamed to anoth- Artifacts the navigation console. er location and performing in a Star -Costumes Trek-inspired scene. 100+ props and artifacts -Props from the five Star Trek television series KHAAAAN! video booth and many of the films including: where visitors can recreate the -Scripts, Production -original series tricorder memorable scene from Star Trek II: Documents/Storyboards -communicator phaser The Wrath of Khan -a Borg cube -Sketches -Klingon disruptor pistol Spaceship filming models -Models -Tribbles, and more of the Enterprise, USS Excelsior, a Klingon battle cruiser, and Rare costumes Deep Space Nine space station Films including: Spock’s tunic worn by -Five interpretive -

Is Klingon an Ohlonean Language? — a Comparison of Mutsun and Klingon

Is Klingon an Ohlonean Language? | A Comparison of Mutsun and Klingon Dick Grune [email protected] April 19, 1996 1 Introduction Klingon is an artificial language designed by Marc Okrand [1] in 1985 for Paramount Pictures Cor- poration, to serve as the language of the Klingons in the second Star Trek movie and all subsequent Star Trek and spin-off productions. Its best known expression is Qapla'! = Success! Mutsun (pronounced moot-soon, with the short oo of book, and the t and the s well separated) was an American Indian language of the Ohlonean [3] (= Costanoan) family, which, together with Tsimshian in British Columbia, the Mayan languages in Mexico, and many others, is part of the Penutian stock. It was spoken until the beginning of the 20th century around Mission San Juan Bautista, just south of San Francisco, Ca. Its last speaker, Mrs. Ascensi´onSolorsano de Cervantes, died Jan. 29, 1930, at the age of 74. The most accessible work on Mutsun is a grammar produced as a PhD thesis by this same Marc Okrand [2]. So, naturally, the question arises to what degree Klingon was inspired by Mutsun. Already being in the possession of [1] and having recently been able to put my hands on a copy of [2], I set out reading and comparing, in order to find the answer to this question. Those of you who are just after a juicy bit of gossip will be disappointed: No, Klingon is not more similar to Mutsun than it is to any other American Indian language, neither in vocabulary nor in structure. -

Creating “Star Trek CATAN – Federation Space”

Creating “Star Trek CATAN – Federation Space” After Star Trek Catan was so well received, and as many of you asked us to take this joint venture of the two franchises Catan and Star Trek even further towards the “Final Frontier,” we thought long and hard about what kind of game expansion you would enjoy. As we knew that a lot of players liked our Catan Geographies™ maps so much, which take the whole Settlers of Catan experience towards a real map to put settlements in, we thought: Let us take Star Trek Catan into a “real” region of space to put our little NCC-1701 spaceships in. The crucial question was: Is there a region of space sufficiently “real” inside the Star Trek – The Original Series time period? After a bit of research, we discovered this wonderful map titled “The Explored Galaxy” over at the Memory Alpha wiki. As it turned out, this was “as real as it could get,” as it had been first shown hanging on a wall in none other than Captain James T. Kirk’s quarters in the Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country motion picture (and subsequently in various episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation). Every true Star Trek fan knows that this particular map depicts a lot of the known and beloved locations shown in The Original Series of the 60s, and some of those from The Animated Series of the 70s. We took great effort to investigate and cross-reference all these depicted celestial bodies with their respective episodes. © CATAN GmbH - Page 1 We then added a couple of planets that were not actually shown on this map but that we would really want to have in our game, and tried to pinpoint their locations according to mostly in-canon and sometimes semi-canon sources. -

Trekmovie Picks ΠBest Star Trek Products 2010 | Trekmovie.Com

2/2/2011 TrekMovie Picks – Best Star Trek Produ… news star trek (2009 film) tos remastered about fan reviews (star trek film) live chat Ads by Google Star Trek Ship Star Trek 11 Star Trek Quiz Star Trek search go! TrekMovie Picks – Best Star Trek Products 2010 January 16, 2011 by TrekMovie.com Staff , Filed under: Merchandise, Review, Trek Franchise, TrekMovie.com , trackback 2011 is here but today TrekMovie begins a look back at 2010 to pick the best of year in terms of Star Trek products, from toys to wearable items, to posters. Check out the winners below. 2010 in Star Trek products 2010 was not the best year for Star Trek products in terms of quantity of new releases. Most of the new products were themed around the original 1960s Star Trek which is ironic Latest Articles for a year following the big success of a new movie with fresh faces and designs. There Brannon Braga Explains Why No Gay Characters On Star Trek: also seemed to be much less of certain products, such as toys being produced. Not Forward Thinking However, while there may be a limitation of supply, there were certainly products of both Star Trek Stars At Sundance: Yelchin Taks ‘Ridiculous Happy’ great fun and quality this year to celebrate. TrekMovie presents its fourth annual look at Chekov + Quinto Sells Margin Call + Photos w/ Saldana the best Star Trek products and collectibles of the year as selected by the editors. Nimoy Planning Return To Fringe Hopefully, 2011 will bring a diversity of products in much greater numbers. -

2007 EDITION STARFLEET MARINE CORPS Xenostudies Andorian Manual

2007 EDITION STARFLEET MARINE CORPS Xenostudies Andorian Manual 2007 Edition This manual is published by the STARFLEET Marine Corps, a component of STARFLEET, the International Star Trek Fan Association, Inc., and released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/). You may freely copy, distribute, display, and perform this manual, but all other uses are strictly prohibited unless written permission is received from the Commandant or Deputy Commandant, STARFLEET Marine Corps. The STARFLEET Marine Corps holds no claims to any trademarks, copyrights, or other properties held by Paramount, other such companies or individuals. Published: October 2007 XA Manual Contents Part 1 - Introduction ��������������������������������������������������������1 Copyright and Disclaimer ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Pronoun Disclaimer ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Acknowledgements ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 1 Reporting Authority ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Part 2 - Andoria ����������������������������������������������������������������2 The Solar System ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 2 Andoria (Procyon VIII) ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ -

USS ENTERPRISE from STAR TREK (TOS)

U.S.S. ENTERPRISE from STAR TREK (TOS) If printed 17 inches tall (from black-outlined edge to black-outlined edge) the scale of these drawings is 1/350. LAYOUT: DECKS 2 and 3 PAGE 2 of 18 0 5 10 15 20 COPYRIGHT 2020 - PARAMOUNT DRAWN BY: Jim Botaitis METERS STELLAR ION ION CARTOGRAPHY Recessed floor of STUDY STUDY center of Bridge SCIENCE Recessed floor of SCIENCE EQUIPMENT center of Bridge EQUIPMENT AND SENSORS AND SENSORS TL EMERGENCY EMERGENCY HATCH HATCH DN 59 DN UP UP 1 - 10 UP PWT 1 - 10 UP PWT DN E DN E DN DN Recessed floor Recessed floor of entire Bridge EL Maximum of entire Bridge Maximum Headroom Headroom HIGH HIGH ENERGY BIOLOGY ENERGY DECK 2: SCIENCE LABORATORIES DECK 2: V.I.P. QUARTERS GEOLOGY BOTANY (REC ROOM 6) COMMUNICATIONS WATER STORAGE EL 70 UP TL UP 2 - 3 1 - 10 DN DN E ONLY ES PWT C UP EL OFFICERS' LOUNGE PHYSICS CHEMISTRY DECK 3: SCIENCE LABORATORIES / LOUNGE NOTES DECK 2 DECK 3 I adjusted the spacing of the top 4 decks for a better fit, but the Bridge (and the recess in the center of Stairs for the emergency exit on Deck 2 start on Deck 4 and continue up from there past this level. the Bridge) still affects Deck 2 too much. Yes, stairs were never mentioned or seen. Does that mean they do not exist? TMoST says this deck has Science Labs. This may be what was located here initially. However. An Officers' Lounge was never mentioned or seen. -

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

![Women at Warp Episode 38: Disability and Ableism in Star Trek [Bumper] Hi, This Is Melinda Snodgrass and You're Listening to W](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4877/women-at-warp-episode-38-disability-and-ableism-in-star-trek-bumper-hi-this-is-melinda-snodgrass-and-youre-listening-to-w-644877.webp)

Women at Warp Episode 38: Disability and Ableism in Star Trek [Bumper] Hi, This Is Melinda Snodgrass and You're Listening to W

Women at Warp Episode 38: Disability and Ableism in Star Trek [bumper] Hi, this is Melinda Snodgrass and you’re listening to Women at Warp. [end bumper] [audio of LeVar Burton] It was really difficult on a weekly basis for the audience to see what Geordi saw. In fact, we never really successfully did it, in the seven years that we did Next Generation. In fact, the audience has never seen it in any of the movies, the audience has never seen what Geordi sees. Geordi sees all of the electromagnetic spectrum. That means he sees everything from infrared to x- ray. Geordi sees sound, ok? [end audio clip] JARRAH: Hi and welcome to Women at Warp. Join us as our crew of four women Star Trek fans boldly go on our bi-weekly mission to explore our favourite franchise. My name is Jarrah. Thanks for tuning in. Today, with us we have crewmembers Andi−− ANDI: Hello JARRAH: And Sue. SUE: Hi, everybody. JARRAH: We also have a very special guest, Kari. And I’m going to get you to introduce yourself and maybe tell us a bit about how you first got into Star Trek. KARI: Yeah, sure. So as you mentioned, my name is Kari. I’ve loved Star Trek since early high school. I started with Voyager because I was particularly inspired by the strong female role models. I loved Janeway. I’m also planning to get my PhD in sociology. So because of that and my analytical nature, Star Trek has always been a very deep well for me to dig into, in terms of having interesting things to analyze. -

STAR TREK the TOUR Take a Tour Around the Exhibition

R starts CONTents STAR TREK THE TOUR Take a tour around the exhibition. 2 ALL THOSE WONDERFUL THINGS.... More than 430 items of memorabilia are on show. 10 MAGIC MOMENTS A gallery of great Star Trek moments. 12 STAR TREK Kirk, Spock, McCoy et al – relive the 1960s! 14 STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION The 24th Century brought into focus through the eyes of 18 Captain Picard and his crew. STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE Wormholes and warriors at the Alpha Quadrant’s most 22 desirable real estate. STAR TREK: VOYAGER Lost. Alone. And desperate to get home. Meet Captain 26 Janeway and her fearless crew. STAR TREK: ENTERPRISE Meet the newest Starfleet crew to explore the universe. 30 STARSHIP SPECIAL Starfleet’s finest on show. 34 STAR TREK – THE MOVIES From Star Trek: The Motion Picture to Star Trek Nemesis. 36 STAR trek WELCOMING WORDS Welcome to Star TREK THE TOUR. I’m sure you have already discovered, as I have, that this event is truly a unique amalgamation of all the things that made Star Trek a phenomenon. My own small contribution to this legendary story has continued to be a source of great pride to me during my career, and although I have been fortunate enough to have many other projects to satisfy the artist in me, I have nevertheless always felt a deep and visceral connection to the show. But there are reasons why this never- ending story has endured. I have always believed that this special connection to Star Trek we all enjoy comes from the positive picture the stories consistently envision.