Ideological Conditioning of Martial Arts Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authentic Specialized Martial Arts Training in India

Lamka Shaolin Disciple’s Union www.kungfudisciples.com Lamka Shaolin Disciples’ Union SPECIALIZED MARTIAL ARTS COURSE INFO http://www.kungfudisciples.com Introducing Authentic Specialized Martial Arts Training in India 1 Lamka Shaolin Disciple’s Union www.kungfudisciples.com BAGUA ZHANG: [12 Classes a Month] Introduction: Bagua Zhang 八卦掌 Bagua Zhang is a martial art that has existed in various forms for millennia, practiced secretly by Taoist hermits before it emerged from obscurity in the late 19th century C.E. The most famous modern proponent, Dong Hai Chuan, became the bodyguard of the Empress Dowager, and was a teacher well respected by China’s most famous masters. 1. It is characterized by fast circular footwork, agile body movements, and lightning-fast hands. It is one of the famous three Neijia (Internal) styles which also include Tai Chi Quan and Xingyi Quan. 2. It teaches the student to “Walk like a dragon, retrieve and spin like an ape, change momentum like an eagle, and be calm and steady like a waiting tiger.” The use of open palms instead of fists, and the use of “negative space” is one of the things that makes Bagua Zhang particularly good for defeating multiple opponents. 3. Bagua Zhang contains powerful strikes. But the emphasis on flow and constant change is what gives this art its versatility. The options to choose between strikes, throws, joint locks, pressure point control, and varying degrees of control, make this art useful for self-defense and for law enforcement. 4. Bagua Zhang training is very aerobic, and emphasizes stability and agility. -

Episode 327 – Paradigm Shifts | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 327 – Paradigm Shifts | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hey everyone thanks for coming by this is whistlekickmartialartsradio and you're listening to episode 327. Today we're going to talk about Jeet Kune Do. My name's Jeremy Lesniak, I'm your host for the show on the founder at whistlekickmartialarts and I love traditional martial arts. I'm doing it all my life and now it's my job, it's my job to help you love the martial arts even more and I'll do whatever I can to make that happen. If you wanna check out our products our projects our services all the stuff we've got going on you could find that at whistlekick.com and you can find the show notes for this and all of our other episodes at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com most of them have a transcript. We're actually going back and transcribing all of the old episodes. So if you're in a spot where you can't listen but you could read you might want to check those out or of course for our friends who are hearing impaired we wanna make sure that we give as much as we can to all martial artists regardless of how they take in their entertainment. Let's talk about Jeet Kune Do. We've spent a lot of time talking about Bruce Lee on the show especially lately episode 305 with Mr. Matthew Polly talking about his book Bruce Lee a life received at ton of attention and we thought it might be good idea to dig deeper into part of the legacy that Bruce Lee left namely the martial arts style that isn't the style in a sense Jeet Kune Do. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Aikido XXXIX

Anno XXXIX(gennaio 2008) Ente Morale D.P.R. 526 del 08/07/1978 Periodico dell’Aikikai d’Italia Associazione di Cultura Tradizionale Giapponese Via Appia Nuova 37 - 00183 Roma ASSOCIAZIONE DI CULTURA TRADIZIONALE GIAPPONESE AIKIKAI D’ITALIA 30 ANNI DI ENTE2008 MORALE 3NOVEMBRE0 Sommario 02 - Editoriale 03 - Comunicati del fondo Hosokawa 04 - Nava, estate 2007... 05 - Ricordi:Giorgio Veneri - Cesare Abis 07 - ..a proposito di Ente Morale 10 - Lezione agli insegnanti dell’Aikikai d’Italia del maestro Hiroshi Tada Composizione dell’Aikikai d’Italia 14 - Le due vie del Budo: Shingaku no michi e Shinpo no michi Presidente 15 - Premessa allo studio dei principi Franco Zoppi - Dojo Nippon La Spezia di base di aikido 23 - La Spezia, Luglio 2007 Vice Presidente 25 - Roma, Novembre 2007 Marino Genovesi - Dojo Fujiyama Pietrasanta 26 - I giardini del Maestro Tada Consiglieri 28 - Nihonshoki Piergiorgio Cocco - Dojo Musubi No Kai Cagliari 29 - Come trasformarsi in un enorme macigno Roberto Foglietta - Aikido Dojo Pesaro Michele Frizzera - Dojo Aikikai Verona 38 - Jikishinkage ryu kenjutsu Cesare Marulli - Dojo Nozomi Roma 39 - Jikishinkageryu: Maestro Terayama Katsujo Alessandro Pistorello - Aikikai Milano 40 - Nuove frontiere: il cinema giapponese Direttore Didattico 52 - Cinema: Harakiri Hiroshi Tada 55 - Cinema: Tatsuya Nakadai Vice Direttori Didattici 58 - Convegno a Salerno “Samurai del terzo millennio” Yoji Fujimoto Hideki Hosokawa 59 - Salute: Qi gong Direzione Didattica 61 - Salute: Tai ji quan- Wu Shu - Aikido Pasquale Aiello - Dojo Jikishinkai -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

Do You Know Bruce Was Known by Many Names?

Newspapers In Education and the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience present ARTICLE 2 DO YOU KNOW BRUCE WAS KNOWN BY MANY NAMES? “The key to immortality is living a life worth remembering.”—Bruce Lee To have one English name and one name in your family’s mother tongue is common Bruce began teaching and started for second and third generation Asian Americans. Bruce Lee had two names as well as his first school here in Seattle, on a number of nicknames he earned throughout his life. His Chinese name was given to Weller Street, and then moved it to him by his parents at birth, while it is said that a nurse at the hospital in San Francisco its more prominent location in the where he was born gave him his English name. While the world knows him primarily University District. From Seattle as Bruce Lee, he was born Lee Jun Fan on November 27, 1940. he went on to open schools in Oakland and Los Angeles, earning Bruce Lee’s mother gave birth to him in the Year of the Dragon during the Hour of the him the respectful title of “Sifu” by Dragon. His Chinese given name reflected her hope that Bruce would return to and be his many students which included Young Bruce Lee successful in the United States one day. The name “Lee Jun Fan” not only embodied the likes of Steve McQueen, James TM & (C) Bruce Lee Enterprises, LLC. All Rights Reserved. his parents’ hopes and dreams for their son, but also for a prosperous China in the Coburn, Kareem Abdul Jabbar, www.brucelee.com modern world. -

Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do Terminology

THE SCIENCE OF FOOTWORK The JKD key to defeating any attack By: Ted Wong "The essence of fighting is the art of moving."- Bruce Lee Bruce Lee E-Paper - II Published by - The Wrong Brothers Click Here to Visit our Home page Email - [email protected] Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do Terminology Chinese Name English Translation 1) Lee Jun Fan Bruce Lee’s Chinese Name 2) Jeet Kune Do Way of the Intercepting Fist 3) Yu-Bay! Ready! 4) Gin Lai Salute 5) Bai Jong Ready Position 6) Kwoon School or Academy 7) Si-jo Founder of System (Bruce Lee) 8) Si-gung Your Instructor’s Instructor 9) Si-fu Your Instructor 10) Si-hing Your senior, older brother 11) Si-dai Your junior or younger brother 12) Si-bak Instructor’s senior 13) Si-sook Instructor’s junior 14) To-dai Student 15) Toe-suen Student’s Student 16) Phon-Sao Trapping Hands 17) Pak sao Slapping Hand 18) Lop sao Pulling Hand 19) Jut sao Jerking Hand 20) Jao sao Running Hand 21) Huen sao Circling Hand 22) Boang sao Deflecting Hand (elbow up) 23) Fook sao Horizontal Deflecting Arm 24) Maun sao Inquisitive Hand (Gum Sao) 25) Gum sao Covering, Pressing Hand, Forearm 26) Tan sao Palm Up Deflecting Hand 27) Ha pak Low Slap 28) Ouy ha pak Outside Low Slap Cover 29) Loy ha pak Inside Low Slap Cover 30) Ha o’ou sao Low Outside Hooking Hand 31) Woang pak High Cross Slap 32) Goang sao Low Outer Wrist Block 33) Ha da Low Hit 34) Jung da Middle Hit 35) Go da High Hit 36) Bil-Jee Thrusting fingers (finger jab) 37) Jik chung choi Straight Blast (Battle Punch) 38) Chung choi Vertical Fist 39) Gua choi Back Fist 40) -

View Book Inside

YMAA PUBLICATION CENTER YMAA is dedicated to developing the most clear and in-depth instructional materials to transmit the martial legacy. Our books, videos and DVDs are created in collab- oration with master teachers, students and technology experts with a single-minded purpose: to fulfill your individual needs in learning and daily practice. This downloadable document is intended as a sample only. To order this book, please click on our logo which will take you to this product’s page. An order button can be found at the bottom. We hope that you enjoy this preview and encourage you to explore the many other downloadable samples of books, music, and movies throughout our website. Most downloads are found at the bottom of product pages in our Web Store. Did you know? • YMAA hosts one of the most active Qigong and martial arts forums on the internet? Over 5,000 registered users, dozens of categories, and over 10,000 articles. • YMAA has a free quarterly newsletter containing articles, interviews, product reviews, events, and more. YMAA Publication Center 1-800-669-8892 [email protected] www.ymaa.com ISBN647 cover layout 9/13/05 2:20 PM Page 1 Martial Arts • Tai Chi Chuan • Alternative Health THE TAI CHIBOOK THE TAI THE GET THE MOST FROM YOUR TAI CHI PR ACTICE TAIREFINING AND ENJOYING CHI A LIFETIME OF PRACTICE The Tai Chi Book is a detailed guide for students who have learned a Tai Chi form and want to know more. It also introduces beginners to the principles behind great Tai Chi, and answers common questions. -

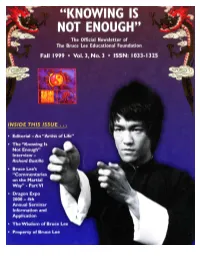

Newsletter Jfjkd-Nucleus Vol-3-3.Pdf

By the term An "Artist of Life" "artist of life" Lee was By Iohn Little referring to the process of By the time you receive this newsletter, one of the most learning to be important books ever printed about Bruce Lee will be entering an honest bookstores. It is entitled "Bruce Lee: Artist of Life," and within its communicator pages lie the essential writings of Bruce Lee. of one's This book represents a true milestone in getting to know the innermost "real" Bruce Lee and allows Bruce a voice in how his art, his life feelings. One and his beliefs are to be presented to future generations. Much of who was willing this material has never been published before, and even the to lay bare his material that has been published, has never been presented in its soul for the original format - just the way it was when Bruce Lee originally purpose of wrote it. honest The book represents Volume Six of the highly-acclaimed Bruce communication Lee Library Series, published by the Chailes E. Tuttle Publishing with another Company and the publishers were so impressed with its content human being, that they decided to release it in a specialhardbound edition, and not get making it the first book in the series to be presented in such a caught up in fashion. the various In an on-going attempt to present to our members the latest forms of information about Bruce Lee and this teachings as it becomes societal role- available, we are here presenting (with permission from the playing (i.e., publisher) series' editor, lohn Little's "introduction" to this self-image creation). -

Libros De Artes Marciales: Guia Bibliografica Comentada"

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTONOMA DEMEXICO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS COLEGIO DE BIBUOTECOLOGIA "LIBROS DE ARTES MARCIALES: GUIA BIBLIOGRAFICA COMENTADA" T E s 1 N A QUE PARA OBTENER EL TITULO DE LICENCIADO EN BIBLIOTECOLOGIA P R E S E N T A JAIME ANAXIMANDRO GUTIERREZ REYES ASESOR: LIC. MIGUEL ANGEL AMAYA RAMIREZ MEXICO, D.F. 2003 UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Agradecimientos: A Shirel Yamile, mi pequeña princesa, a quien adoro. A mis padres, gracias a ellos he podido llegar hasta aquí. A mi asesor, el Licenciado Miguel Ángel Amaya Ramírez, por su guía y consejos. coA mis sinodales, por su ayuda y valiosas observaciones: Lic. Patricia de la Rosa Valgañon Lic. María Teresa González Romero Ing. René Pérez Espinosa Lic. Cesar Augusto RamÍrez Velázquez CONTENIDO INTRODUCCIÓN CAPITULO l. LAS ARTES MARCIALES 1.1 Definición. 1 1.2. Antecedentes. 2 1.3. Tipología 7 1.3.1. Artes marciales practicadas como deporte 7 1.3.2. Artes marciales practicadas como métodos reales de combate 13 1.3.3. -

Tai Chi Push Hands Cloud Hands Tai Chi Qigong Cleansing Traditional

Monday! Tuesday! Wednesday! Thursday Friday Empowerment Qigong ! Qigong" Cloud Hands Kung Fu " Qigong! Healing! Cleansing! Tai Chi Fitness! 5:30 PM! 5:30 PM! 5:30 PM! 5:30 PM 5:30 PM! Need more focus, Release pain and reverse Use the 9 Qigong Jewels to Feel the flow with easy Tai Kung Fu masters are fit, discipline, or direction in illness with the 9 Qigong energetically cleanse the Chi techniques that flexible, agile, and strong, your life? Then this class Jewels.! skin, the muscles, the anyone can enjoy. even into old age. Learn is for you.! meridians, the organs, and their simple secrets.! April" the bones.! 2012! Schedule! Athleticism: Very Easy Athleticism: Very Easy Athleticism: Easy Athleticism: Medium Athleticism: Medium! Qigong " Kung Fu " Qigong " One Finger " Flowing Zen 101 " is a prerequisite Flow! Fitness! Healing" Zen! Classes are for for all classes.! 6:15 PM! 6:15 PM! 6:15 PM! 6:15 PM! Members only. Flow gracefully through Kung Fu masters are fit, Release pain and reverse Grandmaster Wong’s For more the 18 Lohan Hands as you flexible, agile, and strong, illness with the 9 Qigong favorite exercise-- a Memberships may information " build health, vitality, even into old age. Learn Jewels.! powerful Qigong technique be purchased online please call:! flexibility, and balance.! their simple secrets.! once reserved exclusively for Shaolin Kung Fu or at the studio. disciples.! (352) 672-7613 or visit" Athleticism: Medium Athleticism: Medium Athleticism: Very Easy Athleticism: Easy! Beginners must FlowingZen.com take 5 blue classes before moving to Traditional" Traditional" Traditional" Tai Chi red classes. -

Southern Mantis System Are Short Range, Based on Inch Force Power That Comes from Tendon Contraction

Southern Praying Mantis system written by F.Blanco 1.ORIGINS In 1644 AD, the Manchurian tribe had invaded China and defeated the Ming dynasty rulers. Ming loyalist, nobles and soldiers, escaped and went south. As pointed by the Wushu historian Salvatore Canzonieri, many of this rebels relocated in the The Honan Shaolin. The Ching rulers discovered the temple was a focus of resistance and they burned Songshan Shaolin in 1768. After the destruction of the temple many of the Chu family and other nobles and also many Shaolin monks from Honan moved to the South Shaolin temples (Fujian and Jian Shi). The Chu Gar style legend mentions Tang Chan, (his real name was Chu Fook Too or Chu Fook To), who belonged to the Ming Imperial court (1) as one of this rebels that emigrated to the Southern temples. At the Fujian temple (located in the Nine Little Lotus Mountains) the monks and rebels shortened the time it took to master the boxing styles from 10 years to 3 years with the purpose of train quickly the fighters to overthrow the Ching rulers and restore the Ming dynasty. The Chu Gar legend says that Chu Fook Too became abbot in the Fujian temple and changed his name to "Tung Sim" (anguish) due to his deep anguish and hatred for the Ching's reign of terror and suffering. In the style's legend he was the person that developed the Southern Praying Mantis style. The monks (or Chu Fook Too himself) developed kung fu fighting styles that were faster to learn, based on close range fighting, designed to defeat a martial art skilled opponent (Manchu soldiers and Imperial Guard) with fast, powerful chains of attacks that left no time for counter-attacks.