Foxwoods Casino Philadelphia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status NOT EQUAL to D

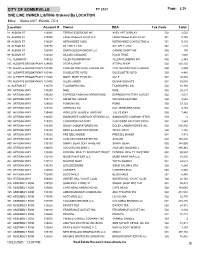

CITY OF SOMERVILLE FY 2021 Page: 1/29 ONE LINE OWNER LISTING Ordered By LOCATION Filter: Status NOT EQUAL TO d Location Account # Owner DBA Tax Code Total 81 ALBION ST 112090 TERRACE DESIGNS INC AVEY ART DISPLAY 502 3,520 83 ALBION ST 135580 FOUR WHEELS AUTO LLC FOUR WHEELS AUTO LLC 501 5,140 99 ALBION ST 136630 HERNANDEZ ALEX HERNANDEZ CONSULTING & 501 9,130 99 ALBION ST 109770 SILLARI T J INC SILLARI T J INC 502 2,210 99 ALBION ST 126530 SHAW DESIGN GROUP LLC CANINE SHOP THE 502 190 99 ALBION ST 133560 SILLARI CAROLINE ROCK TRIBE 501 1,060 112 ALBION ST 104820 ALLEN PLUMBING INC ALLEN PLUMBING INC 502 2,340 105 ALEWIFE BROOK PKWY 128680 STOP & SHOP STOP & SHOP 502 420,120 115 ALEWIFE BROOK PKWY 121390 CONTAN DISCOUNT LIQUOR INC CONTAN DISCOUNT LIQUOR 502 2,800 325 ALEWIFE BROOK PKWY 105540 DUCEUOTTE AUTO DUCEUOTTE AUTO 502 4,460 379 ALEWIFE BROOK PKWY 111540 MOBIL MART PLUS INC GULF 502 20,860 379 ALEWIFE BROOK PKWY 121450 ALLEN JAMES DUNKIN DONUTS 501 25,030 30 ALSTON ST 112570 FLAGRAPHIC INC FLAGRAPHIC INC 502 10,790 300 ARTISAN WAY 130290 NIKE NIKE 502 25,210 301 ARTISAN WAY 130280 EXPRESS FASHION OPERATIONS EXPRESS FACTORY OUTLET 502 3,510 330 ARTISAN WAY 129710 AM RETAIL GROUP WILSONS LEATHER 502 4,540 341 ARTISAN WAY 129660 PUMA NA INC PUMA 502 33,120 360 ARTISAN WAY 129720 STERLING INC KAY JEWELERS #2962 502 4,150 361 ARTISAN WAY 136440 WORLD OF JEANS & TOPS INC TILLYS #263 502 7,440 370 ARTISAN WAY 136450 SAMSONITE COMPANY STORES LLC SAMSONITE COMPANY STOR 503 0 390 ARTISAN WAY 129700 CONVERSE FACTORY CONVERSE FACTORY #3789 -

03.031 Socc04 Final 2(R)

STATEOF CENTER CITY 2008 Prepared by Center City District & Central Philadelphia Development Corporation May 2008 STATEOF CENTER CITY 2008 Center City District & Central Philadelphia Development Corporation 660 Chestnut Street Philadelphia PA, 19106 215.440.5500 www.CenterCityPhila.org TABLEOFCONTENTSCONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 OFFICE MARKET 2 HEALTHCARE & EDUCATION 6 HOSPITALITY & TOURISM 10 ARTS & CULTURE 14 RETAIL MARKET 18 EMPLOYMENT 22 TRANSPORTATION & ACCESS 28 RESIDENTIAL MARKET 32 PARKS & RECREATION 36 CENTER CITY DISTRICT PERFORMANCE 38 CENTER CITY DEVELOPMENTS 44 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 48 Center City District & Central Philadelphia Development Corporation www.CenterCityPhila.org INTRODUCTION CENTER CITY PHILADELPHIA 2007 was a year of positive change in Center City. Even with the new Comcast Tower topping out at 975 feet, overall office occupancy still climbed to 89%, as the expansion of existing firms and several new arrivals downtown pushed Class A rents up 14%. For the first time in 15 years, Center City increased its share of regional office space. Healthcare and educational institutions continued to attract students, patients and research dollars to downtown, while elementary schools experienced strong demand from the growing number of families in Center City with children. The Pennsylvania Convention Center expansion commenced and plans advanced for new hotels, as occupancy and room rates steadily climbed. On Independence Mall, the National Museum of American Jewish History started construction, while the Barnes Foundation retained designers for a new home on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Housing prices remained strong, rents steadily climbed and rental vacancy rates dropped to 4.6%, as new residents continued to flock to Center City. While the average condo sold for $428,596, 115 units sold in 2007 for more than $1 million, double the number in 2006. -

Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description

MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION FUND APPLICATION Center City District: Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description The Center City District (CCD), a private-sector sponsored business improvement district, authorized under the Commonwealth’s Municipality Authorities Act, seeks to improve the open area and entrances to public transit between the two original Penn Center buildings, bounded by Market Street and JFK Boulevard and 15th and 16th Streets. In 2014, the CCD completed the transformation of Dilworth Park into a first class gateway to transit and a welcoming, sustainably designed civic commons in the heart of Philadelphia. In 2018, the City of Philadelphia completed the renovations of LOVE Park, between 15th and 16th Street, JFK Boulevard and Arch Street. The adjacent Penn Center open space should be a vibrant pedestrian link between the office district and City Hall, a prominent gateway to transit and an attractive setting for businesses seeking to capitalize on direct connections to the regional rail and subway system. However, it is neither well designed nor well managed. While it is perceived and used as public space, its divided ownership between the two adjacent Penn Center buildings and SEPTA has long hampered efforts for a coordinated improvement plan. The property lines runs east/west through the middle of the plaza with Two Penn Center owning the northern half, 1515 Market owning the southern half and neither party willing to make improvements without their neighbor making similar improvements. Since it opened in the early 1960s, Penn Center plaza has never lived up to its full potential. The site was created during urban renewal with the demolition of the above ground, Broad Street Station and the elevated train tracks that ran west to 30th Street. -

Regional Rail

STATION LOCATIONS CONNECTING SERVICES * SATURDAYS, SUNDAYS and MAJOR HOLIDAYS PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TERMINALS E and F 37, 108, 115 )DUH 6HUYLFHV 7UDLQ1XPEHU AIRPORT INFORMATION AIRPORT TERMINALS C and D 37, 108, 115 =RQH Ê*Ë6WDWLRQV $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 $0 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDOV( ) TERMINAL A - EAST and WEST AIRPORT TERMINAL B 37, 108, 115 REGIONAL RAIL AIRPORT $LUSRUW7HUPLQDOV& ' D American Airlines International & Caribbean AIRPORT TERMINAL A EAST 37, 108, 115 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDO% British Airways AIRPORT TERMINAL A WEST 37, 108, 115 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDO$ LINE EASTWICK (DVWZLFN Qatar Airways 37, 68, 108, 115 To/From Center City Philadelphia D 8511 Bartram Ave & D 3HQQ0HGLFLQH6WDWLRQ Eastern Airlines PENN MEDICINE STATION & DDWK6WUHHW6WDWLRQ ' TERMINAL B 3149 Convention Blvd 40, LUCY & DD6XEXUEDQ6WDWLRQ ' 215-580-6565 Effective September 5, 2021 & DD-HIIHUVRQ6WDWLRQ ' American Airlines Domestic & Canadian service MFL, 9, 10, 11, 13, 30, 31, 34, 36, 30th STREET STATION & D7HPSOH8QLYHUVLW\ The Philadelphia Marketplace 44, 49, 62, 78, 124, 125, LUCY, 30th & Market Sts Amtrak, NJT Atlantic City Rail Line • Airport Terminals E and F D :D\QH-XQFWLRQ ² ²² ²² ²² ² ² ² Airport Marriott Hotel SUBURBAN STATION MFL, BSL, 2, 4, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, DD)HUQ5RFN7& ² 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 38, 44, 48, 62, • Airport Terminals C and D 16th St -

Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Tour Format

Tour Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Accessibility Format ET101 Historic Boathouse Row 05/18/16 8:00 a.m. 2.00 LUs/GBCI Take an illuminating journey along Boathouse Row, a National Historic District, and tour the exteriors of 15 buildings dating from Bus and No 1861 to 1998. Get a firsthand view of a genuine labor of Preservation love. Plus, get an interior look at the University Barge Club Walking and the Undine Barge Club. Tour ET102 Good Practice: Research, Academic, and Clinical 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 1.50 LUs/HSW/GBCI Find out how the innovative design of the 10-story Smilow Center for Translational Research drives collaboration and accelerates Bus and Yes SPaces Work Together advanced disease discoveries and treatment. Physically integrated within the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Walking Advanced Medicine and Jordan Center for Medical Education, it's built to train the next generation of Physician-scientists. Tour ET103 Longwood Gardens’ Fountain Revitalization, 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 3.00 LUs/HSW/GBCI Take an exclusive tour of three significant historic restoration and exPansion Projects with the renowned architects and Bus and No Meadow ExPansion, and East Conservatory designers resPonsible for them. Find out how each Professional incorPorated modern systems and technologies while Walking Plaza maintaining design excellence, social integrity, sustainability, land stewardshiP and Preservation, and, of course, old-world Tour charm. Please wear closed-toe shoes and long Pants. ET104 Sustainability Initiatives and Green Building at 05/18/16 10:30 a.m. -

REQUEST for PROPOSAL Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Office of Administration / Information Technology Exhibit C – Statement of Work RFP ISSUE DATE November 12, 2008 PROPOSAL DUE DATE January 20, 2009 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Telecommunications RFP Number 6100004339 Introduction This Statement of Work covers activities pertaining to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (“Commonwealth”) voice and data networks. These include: network administration; installations, moves, adds, and changes (IMACs); network operations; network engineering; remote access services; telecom billing, financial administration; premise voice systems; audio and video conferencing; internet services, business partner connectivity; virtual private networking (VPN); circuit/transport technology; end user communication tools; technology refresh; and support and maintenance of the Commonwealth’s Telecommunications Management System. The Offeror will be expected to provide the Services described in this Statement of Work for all Commonwealth locations. Schedule L – Commonwealth Service Locations contain the list of current locations. The Offeror shall provide information on the managed network services using a media that is efficient, easy to use, easily accessible by end users, and subject to approval by the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth expects that the Offeror will bring value to areas in addition to those identified in this Statement of Work. The Offeror should describe any unique capabilities it possesses for assisting the Commonwealth in achieving additional improvements -

Lansdale Doylestown Line Public Timetable Layout 4

SATURDAYS AND SUNDAYS AND MAJOR HOLIDAYS FareServices Train Number 511 515 519 523 527 531 535 539 543 547 551 555 559 563 567 571 575 Zone Ê * Ë Stations AM AM AM AM AM AM PMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPM 4 DDDoylestown 6:28 7:28 8:26 9:26 10:26 11:26 12:26 1:26 2:26 3:26 4:26 5:26 6:26 7:26 8:26 9:26 11:26 4 DDDel Val College 6:31 7:31 8:29 9:29 10:29 11:29 12:29 1:29 2:29 3:29 4:29 5:29 6:29 7:29 8:29 9.29 11:29 4 DDNew Britain F6:33 F7:33 F8:31 F9:31 F10:31 F11:31 F12:31 F1:31 F2:31 F3:31 F4:31 F5:31 F6:31 F7:31 F8:31 F9:31 F11:31 4 DDChalfont 6:39 7:39 8:37 9:37 10:37 11:37 12:37 1:37 2:37 3:37 4:37 5:37 6:37 7:37 8:37 9:37 11:37 4 DDColmar 6:45 7:45 8:43 9:43 10:43 11:43 12:43 1:43 2:43 3:43 4:43 5:43 6:43 7:43 8:43 9:43 11:43 4 D Fortuna 6:47 7:47 8:45 9:45 10:45 11:45 12:45 1:45 2:45 3:45 4:45 5:45 6:45 7:45 8:45 9:45 11:45 4 DDLansdale D 6:51 7:51 8:51 9:51 10:51 11:51 12:51 1:51 2:51 3:51 4:51 5:51 6:51 7:51 8:51 9:51 11:51 4 DDPennbrook 6:53 7:53 8:53 9:53 10:53 11:53 12:53 1:53 2:53 3:53 4:53 5:53 6:53 7:53 8:53 9:53 11:53 4 DDNorth Wales 6:56 7:56 8:56 9:56 10:56 11:56 12:56 1:56 2:56 3:56 4:56 5:56 6:56 7:56 8:56 9:56 11:56 3 D Gwynedd Valley 6:59 7:59 8:59 9:59 10:59 11:59 12:59 1:59 2:59 3:59 4:59 5:59 6:59 7:59 8:59 9:59 11:59 3 D Penllyn 7:02 8:02 9:02 10:02 11:02 12:02 1:02 2:02 3:02 4:02 5:02 6:02 7:02 8:02 9:02 10:02 12:02 3 DDAmbler 7:05 8:05 9:05 10:05 11:05 12:05 1:05 2:05 3:05 4:05 5:05 6:05 7:05 8:05 9:05 10:05 12:05 3 DDFort Washington 7:08 8:08 9:08 10:08 11:08 12:08 1:08 2:08 3:08 4:08 5:08 6:08 7:08 8:08 9:08 10:08 12:08 3 D Oreland 7:11 8:11 9:11 10:11 11:11 12:11 1:11 2:11 3:11 4:11 5:11 6:11 7:11 8:11 9:11 10:11 12:11 3 D North Hills 7:12 8:12 9:12 10:12 11:12 12:12 1:12 2:12 3:12 4:12 5:12 6:12 7:12 8:12 9:12 10:12 12:12 3 D Glenside 7:15 8:15 9:15 10:15 11:15 12:15 1:15 2:15 3:15 4:15 5:15 6:15 7:15 8:15 9:15 10:15 12:15 3 DD Jenkintown-Wyncote 7:18 8:18 9:18 10:18 11:18 12:18 1:18 2:18 3:18 4:18 5:18 6:18 7:18 8:18 9:18 10:18 12:18 2 DDMelrose Park —— ———————————— — —12:21 DD TO CENTER CITY 1 Fern Rock T.C. -

(Between 17Th and 18Th Streets) Philadelphia, PA 19103-2838

Directions to Comcast Center One Comcast Center 1701 John F. Kennedy Boulevard (between 17th and 18th streets) Philadelphia, PA 19103-2838. One Comcast Center is located directly west of Suburban Station. You will be asked to present photo ID upon arriving at the building's security desks. The Comcast Conference Center Reception desk may be reached at 215-286-1145 from 8am to 5:30pm. Traveling from the Airport As you exit the airport, follow the combined “I-95 North and 76 West”. Follow Central Philadelphia I-76 over George Platt Bridge to I-76 West. Follow 76 West until you merge onto I- 676 (Vine Street Expressway) via exit 344 toward Central Philadelphia. Take the exit toward Broad Street/Central Philadelphia and take the 15th Street Ramp to Central Philadelphia. Turn right onto 15th Street and continue until you can turn onto JFK Boulevard. Head two blocks west and end at 1701 JFK Boulevard. (See Parking). There is a train from the airport that runs every ½ hour, from Terminals A, B, C, D, and E. Take the Airport Line to Suburban Station (about a 20 minute ride). Certain hotels will provide transportation at your request. Be sure to inquire when making your reservations. Traveling by Car From North: Take NJ turnpike to exit 4. Take Rt. 73 north to Rt. 38. Take Rt. 38 west to US 30. Take US 30 west over the Benjamin Franklin Bridge to I-676. Go south on 6th Street to Arch Street. Head west on Arch Street and turn left onto 16th Street. -

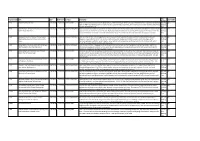

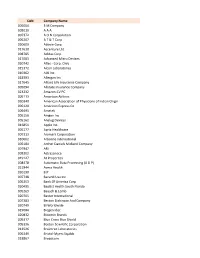

CAN Company Name 005004 3 M Company 005010 a a a 007372 a O N Corporation 005207 a T & T Corp 020609 Abbvie Corp. 017610

CAN Company Name 005004 3 M Company 005010 A A A 007372 A O N Corporation 005207 A T & T Corp 020609 Abbvie Corp. 017610 Accenture Ltd. 008785 Adidas Corp 017083 Advanced Micro Devices 020742 Aflac - Corp. Only 015372 Alcon Laboratories 010362 Aldi Inc 018393 Allergan Inc 017645 Allianz Life Insurance Company 005094 Allstate Insurance Company 023232 Amazon-CV PC 005113 American Airlines 020340 American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin 005120 American Express Co 009491 Ametek 005156 Amgen Inc 005162 Analog Devices 016851 Apple Inc. 005177 Apria Healthcare 007313 Aramark Corporation 010662 Arbonne International 005184 Archer Daniels Midland Company 007947 ARI 005202 Astrazeneca 019127 At Properties 008478 Automatic Data Processing (A D P) 021944 Avera Health 020190 B.P. 007748 Bacardi Usa Inc 005253 Bank Of America Corp 020495 Baptist Health South Florida 005269 Bausch & Lomb 020705 Baxter International 007383 Becton Dickinson And Company 020749 BI Worldwide 019084 Biogen Idec 020832 Bloomin Brands 005317 Blue Cross Blue Shield 005336 Boston Scientific Corporation 013526 Braintree Laboratories 005349 Bristol-Myers Squibb 018867 Broadcom 005357 Brown-Forman 007403 C B S Broadcasting Inc 005383 C V S 005384 Cablevision 010995 Caesars Entertainment Group 019659 Carefusion Corporation 020683 CARFAX 005407 Carolinas Healthcare System 005415 Caterpillar Inc 018396 Cb Richard Ellis Group 021467 CDK Global Inc. 005450 Chevron USA Inc. 007575 Church Of Jesus Christ L D S 005477 Cisco Systems 005481 Citigroup 006352 Citizens Financial Group -

ATRCOUN April 27, 20

January 2016 ▪ Volume 20 ▪ Issue 1 THE FORCE AWAKENS: A were signs of choppiness. The Dow plunged RESURGENCE OF M&A IN in September and the IPO markets have been LAWYER slow to gather steam, with very few successful 2015 IPOs in the fourth quarter. We hate to say it, but the current exuberant pace of M&A deals By Frank Aquila and Melissa Sawyer may not be sustainable unless the capital Frank Aquila and Melissa Sawyer are markets can continue to deliver new, up and partners in the Mergers & Acquisitions Group of Sullivan & Cromwell LLP. The coming companies into the mix of potential views and opinions expressed in this article buyers and targets. Meanwhile, the Fed’s de- are those of the authors and do not necessar- cision to raise interest rates will also surely ily represent those of Sullivan & Cromwell LLP or its clients. have an impact on the M&A environment as Contact: [email protected] or well. [email protected]. After close to a decade of anemic M&A, Best of Enemies: Activism 2015 was “the big year” that dealmakers have Developments been expecting for the last several years. Sig- Activism was somewhat old news in 2015 nicant deals took place across a wide range because activism has largely matured into be- The M&A of sectors and geographies. Dealmaking in ing the “new normal.” The level of engage- health care and life sciences continued to be ment between issuers, activists and institu- very active, but we also saw a lot of deals in tional investors has risen to dizzying heights, consumer and retail (Kraft/Heinz, AB InBev/ with all the attendant professionalization of SABMiller), media (Cablevision/Altice, Charter/Time Warner) and chemicals (Dow/ DuPont, Cytec/Solvay), to name a few IN THIS ISSUE: industries. -

1800 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA

ENTRY FORM DVASE 2018 Excellence in Structural Engineering Awards Program PROJECT CATEGORY (check one): Buildings under $5M Buildings Over $100M Buildings $5M - $15M Other Structures Under $1M Buildings $15M - $40M Other Structures Over $1M Buildings $40M - $100M Single Family Home Approximate Total Project Cost $1,500,000,000 construction cost of Core and Shell Construction $650,000,000 facility submitted: Name of Project: Comcast Technology Center Location of Project: 1800 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA Date construction was Office Stack June of 2018 completed (M/Y): Hotel September 2018 Structural Design Firm: Affiliation: All entries must be submitted by DVASE member firms or members. Architect: Core and Shell: Foster + Partners and Kendall / Heaton Associates Interiors: Foster and Partners and Gensler General Contractor: L.F. Driscoll Company Logo (insert .jpg in box below) Important Notes: Please .pdf your completed entry form and email to [email protected]. Please also email separately 2-3 of the best .jpg images of your project, for the slide presentation at the May dinner and for the DVASE website. Include a brief (approx. 4 sentences) summary of the project for the DVASE Awards Presentation with this separate email. Provide a concise project description in the following box (one page maximum). Include the significant aspects of the project and their relationship to the judging criteria. When completed later this year, Comcast Technology Center will be an urban alternative to the sprawling suburban high-tech campuses of Silicon Valley. This high-density development will be a thriving center of innovation and is expected to produce 2,800 permanent jobs and an annual economic impact of more than $720 million. -

BUCKSCOUNTY Law Enforcement Dispatch Summary

BUCKS COUNTY Law Enforcement Dispatch Summary Bucks County 911 Dispatch All Municipal Police Departments Bucks County Sheriff Department Bucks County Detectives PA State Constables County Emergency Services Regional Police Agencies Department Coverage Full/Part Time Pennridge Regional Police Dept. West Rockhill Twp. Full Time East Rockhill Twp. Full Time Perkasie Police Dept. Self Full Time Sellersville Boro. Full Time Hilltown Twp. Police Dept. Self. Full Time Silverdale Boro. Full Time Newtown Twp. Self Full Time Wrightstown Twp. Full Time Warminster Police Dept. Self Full Time Ivyland Boro. Part Time Pennsylvania State Police Station Patrol Areas Patrol Station Area Responsibility Full/Part Time Trevose Station I-95 Patrol Full Time Hulmeville boro. Part Time Langhorne Boro. Part Time Langhorne Manor Boro. Part Time Dublin Station Bridgeton Twp. Full Time Dublin Boro. Part Time Haycock Twp. Full Time Milford Twp. Full Time Nockamixion Twp. Full Time Richland Twp. Part Time Richlandtown Boro. Full Time Trumbauersville Boro. Full Time Philadelphia Area Communications © 2002 Page 1 BUCKS COUNTY County Digital 500 Mhz Radio System County 500 Mhz Digital TRS Frequency Plan SMARTNET System 1 (North/Central) Freq Input 501.7375 (trunked) 501.1625 (trunked) 501.3625 (trunked) 501.5125 (trunked) 501.5625 (trunked) System 1 Repeater Sites Doylestown, Springtown, Plumstedville, Solebury, Almont, New Hope SMARTNET System 2 (South) Freq Input 501.7625 (trunked) 501.0375 (trunked) 501.1875 (trunked) 501.2125 (trunked) 501.2375 (trunked) 501.2625