Lubbock on Everything: the Evocation of Place in the Music of West Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 Cds for $10 Each!

THOMAS FRASER I #79/168 AUGUST 2003 REVIEWS rQr> rÿ p rQ n œ œ œ œ (or not) Nancy Apple Big AI Downing Wayne Hancock Howard Kalish The 100 Greatest Songs Of REAL Country Music JOHN THE REVEALATOR FREEFORM AMERICAN ROOTS #48 ROOTS BIRTHS & DEATHS s_________________________________________________________ / TMRU BESTSELLER!!! SCRAPPY JUD NEWCOMB'S "TURBINADO ri TEXAS ROUND-UP YOUR INDEPENDENT TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 CDs for $10 each! #1 TMRU BESTSELLERS!!! ■ 1 hr F .ilia C s TUP81NA0Q First solo release by the acclaimed Austin guitarist and member of ’90s. roots favorites Loose Diamonds. Scrappy Jud has performed and/or recorded with artists like the ' Resentments [w/Stephen Bruton and Jon Dee Graham), Ian McLagah, Dan Stuart, Toni Price, Bob • Schneider and Beaver Nelson. • "Wall delivers one of the best start-to-finish collections of outlaw country since Wayton Jennings' H o n k y T o n k H e r o e s " -Texas Music Magazine ■‘Super Heroes m akes Nelson's" d e b u t, T h e Last Hurrah’àhd .foltowr-up, üflfe'8ra!ftèr>'critieat "Chris Wall is Dyian in a cowboy hat and muddy successes both - tookjike.^ O boots, except that he sings better." -Twangzirtc ;w o tk s o f a m e re m o rta l.’ ^ - -Austin Chronlch : LEGENDS o»tw SUPER HEROES wvyw.chriswatlmusic.com THE NEW ALBUM FROM AUSTIN'S PREMIER COUNTRY BAND an neu mu - w™.mm GARY CLAXTON • acoustic fhytftm , »orals KEVIN SMITH - acoustic bass, vocals TON LEWIS - drums and cymbals sud Spedai td truth of Oerrifi Stout s debut CD is ContinentaUVE i! so much. -

Southeast Texas: Reviews Gregg Andrews Hothouse of Zydeco Gary Hartman Roger Wood

et al.: Contents Letter from the Director As the Institute for riety of other great Texas musicians. Proceeds from the CD have the History of Texas been vital in helping fund our ongoing educational projects. Music celebrates its We are very grateful to the musicians and to everyone else who second anniversary, we has supported us during the past two years. can look back on a very The Institute continues to add important new collections to productive first two the Texas Music Archives at SWT, including the Mike Crowley years. Our graduate and Collection and the Roger Polson and Cash Edwards Collection. undergraduate courses We also are working closely with the Texas Heritage Music Foun- on the history of Texas dation, the Center for American History, the Texas Music Mu- music continue to grow seum, the New Braunfels Museum of Art and Music, the Mu- in popularity. The seum of American Music History-Texas, the Mexico-North con- Handbook of Texas sortium, and other organizations to help preserve the musical Music, the definitive history of the region and to educate the public about the impor- encyclopedia of Texas tant role music has played in the development of our society. music history, which we At the request of several prominent people in the Texas music are publishing jointly industry, we are considering the possibility of establishing a music with the Texas State Historical Association and the Texas Music industry degree at SWT. This program would allow students Office, will be available in summer 2002. The online interested in working in any aspect of the music industry to bibliography of books, articles, and other publications relating earn a college degree with specialized training in museum work, to the history of Texas music, which we developed in cooperation musical performance, sound recording technology, business, with the Texas Music Office, has proven to be a very useful tool marketing, promotions, journalism, or a variety of other sub- for researchers. -

Austinmusicawards2017.Pdf

Jo Carol Pierce, 1993 Paul Ray, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and PHOTOS BY MARTHA GRENON MARTHA BY PHOTOS Joe Ely, 1990 Daniel Johnston, Living in a Dream 1990 35 YEARS OF THE AUSTIN MUSIC AWARDS BY DOUG FREEMAN n retrospect, confrontation seemed almost a genre taking up the gauntlet after Nelson’s clashing,” admits Moser with a mixture of The Big Boys broil through trademark inevitable. Everyone saw it coming, but no outlaw country of the Seventies. Then Stevie pride and regret at the booking and subse- confrontational catharsis, Biscuit spitting one recalls exactly what set it off. Ray Vaughan called just prior to the date to quent melee. “What I remember of the night is beer onto the crowd during “Movies” and rip- I Blame the Big Boys, whose scathing punk ask if his band could play a surprise set. The that tensions started brewing from the outset ping open a bag of trash to sling around for a classed-up Austin Music Awards show booking, like the entire evening, transpired so between the staff of the Opera House, which the stage as the mosh pit gains momentum audience visited the genre’s desired effect on casually that Moser had almost forgotten until was largely made up of older hippies of a Willie during “TV.” the era. Blame the security at the Austin Stevie Ray and Jimmie Vaughan walked in Nelson persuasion who didn’t take very kindly About 10 minutes in, as the quartet sears into Opera House, bikers and ex-Navy SEALs from with Double Trouble and to the Big Boys, and the Big “Complete Control,” security charges from the Willie Nelson’s road crew, who typical of the proceeded to unleash a dev- ANY HISTORY OF Boys themselves, who were stage wings at the first stage divers. -

Literary, Subsidiary, and Foreign Rights Agents

Literary, Subsidiary, and Foreign Rights Agents A Mini-Guide by John Kremer Copyright © 2011 by John Kremer All rights reserved. Open Horizons P. O. Box 2887 Taos NM 87571 575-751-3398 Fax: 575-751-3100 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bookmarket.com Introduction Below are the names and contact information for more than 1,450+ literary agents who sell rights for books. For additional lists, see the end of this report. The agents highlighted with a bigger indent are known to work with self-publishers or publishers in helping them to sell subsidiary, film, foreign, and reprint rights for books. All 325+ foreign literary agents (highlighted in bold green) listed here are known to work with one or more independent publishers or authors in selling foreign rights. Some of the major literary agencies are highlighted in bold red. To locate the 260 agents that deal with first-time novelists, look for the agents highlighted with bigger type. You can also locate them by searching for: “first novel” by using the search function in your web browser or word processing program. Unknown author Jennifer Weiner was turned down by 23 agents before finding one who thought a novel about a plus-size heroine would sell. Her book, Good in Bed, became a bestseller. The lesson? Don't take 23 agents word for it. Find the 24th that believes in you and your book. When querying agents, be selective. Don't send to everyone. Send to those that really look like they might be interested in what you have to offer. -

Galenroth.Pdf

1 THE COLONY-a new work by Galen Roth Originally performed in the New Works Lab in the Drake Theatre Union, The Ohio State University – Columbus, Ohio on May 8th, 9th, and 10th 2009. Author / Director.............Galen Roth Artistic Director...............Chris Roche Script Facilitator..............Bernhard Malkmus Lights.................................Kevin Duchon Stage Manager..................Andrea Schimmoeller Cast: Morris................................Jessi Biggert Angela................................Jessica Studer Karen.................................Barbie Papalios Evan...................................Ben Sostrom Artie...................................Mark Hale, Jr. Melody................................Kelsey Bates Guitarist / New Music.......Chris Ray Special thanks to Mark Shanda, Mandy Fox, Alan Woods, Kristine Kearney, and The Ohio State University Theatre Department. The set is divided into seven areas: one room each for Angela, Artie, Karen, Melody and Morris. Karen’s room is in the center, with the others circled around it. The remaining two areas are a small alcove representing a closet, and another small area in front of Karen’s room, which is the entrance to the Colony. All along the walls of the entire space are pictures: photographs and paintings. They are facing backward, for now. As the audience comes in, the artists all lay down a floor pattern in their respective areas. As they finish, Angela goes around and connects all the floor patterns, while the artists do their work. This goes on for a while, so we get the feeling of an existing, working community. Bookend i Morris crosses to Angela’s room. Angela is blind, her eyes covered by gauze. Morris: I need your help. Angela: I hate doing this for you. Morris: I can’t imagine why. Angela: Don’t get smart with me. -

“Mama Tried”--Merle Haggard (1968) Added to the National Registry: 2015 Essay by Rachel Rubin (Guest Post)*

“Mama Tried”--Merle Haggard (1968) Added to the National Registry: 2015 Essay by Rachel Rubin (guest post)* “Mama Tried” original LP cover When Merle Haggard released “Mama Tried” in 1968, it quickly became his biggest hit. But, although in terms of broad reception, the song would be shortly eclipsed by the controversies surrounding Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” (released the next year), “Mama Tried” was a path-breaking song in several significant ways. It efficiently marked important, shaping changes to country music made by the generation of musicians and audiences who came of age post-World War II (as did Haggard, who born in 1937). “Mama Tried,” then, encompasses and articulates developments of both Haggard’s career and artistic focus, and the direction of country music in general. Indeed, Haggard’s own story usefully traces the trajectory of modern country music. Haggard was born near the city of Bakersfield, California, in a converted boxcar. He was born two years after his parents, who were devastated Dust Bowl “Okies,” traveled there from East Oklahoma as part of the migration most famously represented by John Steinbeck in “Grapes of Wrath” (1939)--an important novel that presented and commented on the class-based contempt that “Okies” faced in California. Haggard confronted this contempt throughout his career (and even after his 2016 death, the class- based contempt continues). His family (including Haggard himself) took up a range of jobs, including agricultural work, truck-driving, and oil-well drilling. Labor remained a defining factor of Haggard’s music until he died in 2016, and he frequently found ways to refer to his musicianship as work (making a sharp joke on an album, for instance, about the connection between picking cotton and picking guitar). -

Hidden Kitchens Texas with Host Willie Nelson

Hidden Kitchens Texas with Host Willie Nelson Produced by The Kitchen Sisters (Davia Nelson & Nikki Silva) In collaboration with KUT FM at the University of Texas in Austin & NPR A New NPR Nationwide Special Summer/Fall 2007 Peabody Award-winning producers, The Kitchen Sisters, NPR, and KUT Austin present Hidden Kitchens Texas, a lively, illuminating, sound-rich hour of stories about the Texas experience through food, told by people who find it, grow it, cook it, eat it, sell it, share it, celebrate with it, and write about it. Host, Willie Nelson and Dallas-born actress Robin Wright Penn (whose mother was a Mary Kay Cosmetics Executive), along with some extraordinary tellers, take us across The Lone Star State and share their own hidden kitchen stories in this new special that comes alive in story and sound, laced with soulful array of Texas music. Stories of NASA's space kitchens, cowboy kitchens, oil barrel barbeques, ice houses, chili queens, the birth of the Frito, the birth of the 7-11, the birth of the Slurpee, the birth of the Frozen Margarita, the first barbeque pit on the moon, a car wash kitchen in El Paso, and so much more. intimate, historic, offbeat, profound and wild. As we did with the Hidden Kitchens Morning Edition series, we opened up a Hidden Kitchens hotline across Texas, and listeners called in by the droves with their own tales and tips that we followed to in all kinds of places. “Deep Fried Fuel: A Biodiesel Kitchen Vision, travels to Carl’s Corner Truck stop in Carl’s Corner Texas, a tale of fuel made from farm crops and restaurant grease. -

By Jason Cohen

There and Back Again Jan 2017 – by Jason Cohen In 1962 Terry Allen left Lubbock to pursue what he couldn’t imagine ever happening in his hometown: a life as an artist. More than fifty years later, the sculptor, painter, playwright, and musician behind Juarez and Lubbock (On Everything) is ready for a return. Terry Allen, photographed in Austin, in November 2016. Photograph by Leann Mueller The guide leading incoming freshmen around Texas Tech University on the first Saturday of 2016’s college- football season didn’t look as though he’d been on campus longer than one academic year himself, but he had his patter down. As the group moved from the library to the student union, he pointed out a work commissioned by the school’s public art program and installed in 2003: a hominid-like bronze figure cast entirely from books. While all the students call it “Bookman,” the sculpture’s formal title is a play on the university’s Red Raiders nickname: Read Reader. And there’s a second pun in Bookman’s anatomical construction. “His spine is made out of actual book spines,” the guide observed, before offering his own interpretation of the work. “He’s running to the library to cram for his test. But he’s probably going to fail, because he’s reading a website.” What the collegiate docent didn’t mention was the sculptor, a not-insignificant omission. Bookman sprung from the mind and hands of Lubbock native and one-semester Texas Tech dropout Terry Allen, who is arguably the first of Lubbock’s legendary post-hippie semi-country singer-songwriters. -

Terry Allen:: the AD Interview." Aquarium Drunkard

"Terry Allen:: The AD Interview." Aquarium Drunkard. 2019. Web. Terry Allen :: The AD Interview Terry Allen is a maker of things. A sculptor, illustrator, playwright, collagist, and, perhaps most famously, a singer and songwriter who, over the last five decades, has amassed an extensive catalog of avant-country gold. His 1975 album Juarez, a striking and brilliant concept album that plays as a kind of sunburned, southwestern Badlands, and 1979’s sprawling Lubbock (On Everything), a rollicking and wry send-up of Allen’s West Texas hometown, are rightly held up as unimpeachable masterpieces of proto-americana music. Each have recently received extensive reissues by the North Carolina label Paradise of Bachelors, who will also issue Allen’s forthcoming new album. Juarez by Terry Allen We recently sat down with Allen at the Louver Gallery in Venice, CA, who on June 26th opened Terry Allen: The Exact Moment it Happens in the West, a comprehensive two-story exhibit of Allen’s work across multiple mediums dating from the 1960s to the present. The show will run through September 28th. In an incredibly rare occurrence, Allen also in late July performed two sold out nights at Zebulon on the east side of Los Angeles with an all-star band including Allen’s son Bukka, acclaimed guitar-slinger, Bob Dylan bandleader, and Townes-Van-Zandt-channeler Charlie Sexton, Texan fiddler Richard Bowden, and the singer-songwriter Shannon McNally. Our conversation has been slightly edited for length and clarity. Aquarium Drunkard: One thing that has always interested me about your body of work, particularly your recorded music body of work, is your repertoire over time, where songs such as “Cortez Sail,” or “Four Corners,” or “Red Bird,” have appeared throughout your career in various incarnations, recorded at various times. -

Texas Tech University's Southwest Collection/Special Collections

Oral History Interview of Jesse Taylor Interviewed by: Andy Wilkinson December 12, 2005 Austin, Texas Part of the: Crossroads of Music Archive Texas Tech University’s Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Oral History Program Copyright and Usage Information: An oral history release form was signed by Jesse Taylor on December 12, 2005. This transfers all rights of this interview to the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University. This oral history transcript is protected by U.S. copyright law. By viewing this document, the researcher agrees to abide by the fair use standards of U.S. Copyright Law (1976) and its amendments. This interview may be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes only. Any reproduction or transmission of this protected item beyond fair use requires the written and explicit permission of the Southwest Collection. Please contact Southwest Collection Reference staff for further information. Preferred Citation for this Document: Taylor, Jesse Oral History Interview, December 12, 2005. Interview by Andy Wilkinson, Online Transcription, Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library. URL of PDF, date accessed. The Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library houses almost 6000 oral history interviews dating back to the late 1940s. The historians who conduct these interviews seek to uncover the personal narratives of individuals living on the South Plains and beyond. These interviews should be considered a primary source document that does not implicate the final verified narrative of any event. These are recollections dependent upon an individual’s memory and experiences. The views expressed in these interviews are those only of the people speaking and do not reflect the views of the Southwest Collection or Texas Tech University. -

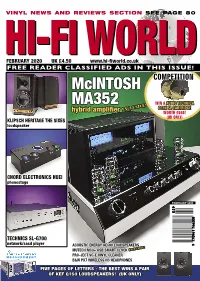

Mcintosh MA352 HYBRID VALVE AMPLIFIER 10 Transistor Power but with Valve Sound

VINYL NEWS AND REVIEWS SECTION SEE PAGE 80 HI-FIHI-FIFEBRUARY 2020 UK £4.50 WORLDWORLDwww.hi-fiworld.co.uk FREE READER CLASSIFIED ADS IN THIS ISSUE! McINTOSH COMPETITION MA352 WIN A AUDIO TECHNICA ! Exclusive OC9X SL CARTRIDGE hybrid amplifier WORTH £660! (UK ONLY) KLIPSCH HERITAGE THE SIXES loudspeaker CHORD ELECTRONICS HUEI phonostage FEBRUARY 2020 TECHNICS SL-G700 network/sacd player ACOUSTIC ENERGY AE500 LOUDSPEAKERS SIVE! MUTECH MC3+ USB SMART CLOCK EXCLU PRO-JECT VC-E VINYL CLEANER MEASUREMENT B&W PX7 WIRELESS NC HEADPHONES FIVE PAGES OF LETTERS - THE BEST WINS A PAIR OF KEF Q150 LOUDSPEAKERS! (UK ONLY) [master] The definitive version. Ultimate performance, bespoke audiophile cable collection Chord Company Signature, Sarum and ChordMusic form the vanguard of our cable ranges. A master collection that features our latest conductor, insulation and connector technology. High-end audiophile quality at a realistic price and each one built to your specific requirements. Arrange a demonstration with your nearest Chord Company retailer and hear the difference for yourself. Designed and hand-built in England since 1985 by a dedicated team of music-lovers. Find more information and a dealer locator at: www.chord.co.uk chordco-ad-HFW-MAR19-MASTER-002a.indd 1 07/05/2019 13:57:32 welcome EDITOR alves can be a bit troublesome. If you’re lucky big ones responsible Noel Keywood for producing power will last a few thousand hours, but then need e-mail: [email protected] replacing. However, small ones that don’t dissipate power will sol- dier on past 10,000 hours – and what’s more they cost little, in the DESIGN EDITOR £10-£20 region.