I Glasgow English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barreiros Simca Peugeot: Evolución De Sus Motorizaciones

Barreiros Simca Peugeot: Evolución de sus motorizaciones Scott Hebrón 1º edición Introducción Existen algunas preguntas a las que muchos aficionados y conductores querrían encontrar una respuesta firme referente a las mecánicas Barreiros Simca Peugeot. ¿Compartían algo de mecánica o motorización los motores entre ellos? ¿Pervivió Barreiros hasta la extinción de los motores Simca, a principios de los 90? ¿Se continuaron fabricando motores de inspiración Simca o Barreiros tras la desaparición de estas marcas? Mucho se ha escrito y divulgado al respecto, a veces con opiniones contrarias, sin embargo lo que se trata de buscar es una respuesta objetiva, contrastada, suficientemente documentada, a ese tipo de preguntas y similares. ¿Por qué es importante esto? Por varias razones: principalmente, por la pervivencia en la mente automovilística de un imperio español con extraordinaria calidad y calado. Asimismo, por la huella en el tiempo que habría dejado palpable la 1 estupenda calidad, tanto mecánica como de construcción y diseño, de unos motores legendarios ya en la época en la que se construyeron. Barreiros nació en 1945 con BECOSA (Barreiros Empresa Constructora, S.A.) y concluyó su actividad automovilística en 1969 cuando Chrysler la absorve totalmente. La americana Chrysler ya había comprado en 1967, dentro de su política de expansión europea, la francesa Simca y la inglesa Rootes. En 1978 Chrysler Europe vende todas sus filiales a la francesa Peugeot, recreando ésta, poco tiempo después, la marca Talbot para unificarlas. Este entramado de fechas y marcas es esencial conocerlo para entender el dispar movimiento de versiones y tecnología que se movió entre tan variadas marcas por esas fechas. -

Ficosa Creates Onboard Ventures, an Open Innovation Initiative to Promote Start-Ups

Onboard Ventures will be presented on Monday 27 February at 12h at 4 Years From Now (4YFN) Ficosa creates Onboard Ventures, an open innovation initiative to promote start-ups This new business unit will support start-ups in advancing their projects and turning them into businesses, relevant and scalable, giving them access to Ficosa’s and Idneo’s assets, such as their technology, global reach, industrialisation and productization capacity, professional’s team, client portfolio and knowledge of the various sectors in which the group operates. Onboard Ventures will promote innovation in the corporation with the aim of expanding business and providing ground-breaking new solutions for clients. Barcelona, 24 February 2017.- Ficosa, a top-tier global provider devoted to the research, development, manufacturing and marketing of high-technology vision, safety, connectivity and efficiency systems for the automotive and mobility sectors, presents Onboard Ventures. This new business unit will support start-ups in advancing their projects and turning them into businesses, relevant and scalable, giving them access to Ficosa’s and Idneo’s assets, the Ficosa group engineering firm specialized in developing high value-added technological products. In this way, Onboard Ventures will give start-ups access to the group’s assets, such as their technology, global reach, industrialisation and productization capacity, professional’s team, client portfolio –which includes the leading automotive brands in the world– and knowledge of the various sectors in which both companies operate (automotive, industrial, energy, medical equipment, etc.). Onboard Ventures has been created with the mission of establishing a mutually beneficial business relationship with technology start-ups. -

Kucukarac.Pdf

M & M SENSOR İKİTELLİ ORG. SAN. BÖLG. ESKOOP SAN. SİT. C-6 BLOK NO:294 BAŞAKŞEHİR / İSTANBUL TEL: +90 212 671 41 80 FAX: +90 212 671 41 90 [email protected] / www.baltechswitches.com SWITCHES SAYFA İÇERİĞİ / INDEX 1 - 15 YAĞ BASINÇ MÜŞÜRLERİ / OIL PRESSURE SWITCHES 16 - 31 HARARET MÜŞÜRLERİ / TEMPERATURE SENDER 32 - 46 SENSÖRLER / SENSORS 47 - 59 GERİ VİTES MÜŞÜRLERİ / REVERSING LIGHT SWITCHES 60 - PNÖMATİK BASINÇ MÜŞÜRLERİ / PNEUMATIC SWITCHES 61 - HİDROLİK FREN MÜŞÜRLERİ / HYDRAULIC STOP LIGHT SWITCHES 62 - MEKANİK FREN MÜŞÜRLERİ / MECHANICAL STOP LIGHT SWITCHES 63 - HAVA BASINÇ MÜŞÜRLERİ / PNEUMATIC STOP LIGHT SWITCHES MADE IN TURKEY BİR TEKNİK GELŞ. MAK. PAZ. SAN. VE TİC. LTD. ŞTİ. İkitelli Org. San. Bölg. Eskoop San. Sit. C6 Blok No:294 İkitelli-Başakşehir / istanbul Tel: +90 212 671 41 80 Fax: +90 212 671 41 90 [email protected] / www.baltechswitches.com YAĞ BASINÇ MÜŞÜRLERİ OIL PRESSURE SWITCHES 1 OEM / ORJ. NO 40.022 Bosch 0344101072 SIMCA SKODA STANDARD Octa 1959-65 Vehículos Europeos F 1959-65 European V cles 1202 1959-65 V Bar 10x1 0,25÷0,50 OEM / ORJ. NO 40.004 Alfa Romeo 60593846 ALFA ROMEO AUDI SKODA 60595694 Alfa 33 1.8 T 1986-94 50. 80. 90. 100 1966-82 105. 120. Estelle. Ra 1977-87 6,35 mm 021 919 081,A,B Alfa 75 1985-92 BMW Fa . 136 Coupé 1987-95 111 919 081, A Alfa 90 1984-87 MERCEDES VOLKSWAGEN 113 919 081 Alfa 155 1992-93 1963-71 Escarabajo/Kafer/Beetle 1960-79 BMW 61 311 351 799 Alfa 164 2.5 Turbo D 1992-98 PORSCHE Dasher. -

The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889-20151

The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889-20151 • JORDI CATALAN Universitat de Barcelona The life cycle of a cluster: some hypotheses Authors such as G. M. P. Swann and E. Bergman have defended the hy- pothesis that clusters have a life cycle.2 During their early history, clusters ben- efit from positive feedback such as strong local suppliers and customers, a pool of specialized labor, shared infrastructures and information externali- ties. However, as clusters mature, they face growing competition in input mar- kets such as real estate and labor, congestion in the use of infrastructures, and some sclerosis in innovation. These advantages and disadvantages combine to create the long-term cycle. In the automobile industry, this interpretation can explain the rise and decline of clusters such as Detroit in the United States or the West Midlands in Britain.3 The objective of this paper is to analyze the life cycle of the Barcelona au- tomobile- industry cluster from its origins at the end of the nineteenth centu- ry to today. The Barcelona district remained at the top of the Iberian auto- mobile clusters for a century. In 2000, when Spain had reached sixth position 1. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the International Conference of Au- tomotive History (Philadelphia 2012), the 16th World Economic History Congress (Stellen- bosch 2012), and the 3rd Economic History Congress of Latin America (Bariloche 2012). I would like to thank the participants in the former meetings for their comments and sugges- tions. This research benefitted from the financial support of the Spanish Ministry of Econo- my (MINECO) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the projects HAR2012-33298 (Cycles and industrial development in the economic history of Spain) and HAR2015-64769-P (Industrial crisis and productive recovery in the Spanish history). -

Descargar Catálogo Completo

Catálogo de Proveedores Introducción Este catálogo recoge las principales capacidades industriales y las innovaciones de producto y proceso más recientes de las empresas proveedoras del Sector de Automoción de Galicia. En el marco del Tercer Plan Estratégico para la Mejora Competitiva del Sector de Automoción de Galicia, P3CA 2025, surge la importancia de promocionar al sector de componentes y servicios de la comunidad gallega. A través de este documento, constantemente actualizado, se refleja la existencia de una red de empresas que ya suministran piezas, desde Galicia, a los principales constructores de automóviles de todo el mundo. El Sector de Automoción de Galicia es uno de los pilares fundamentales de la economía gallega y cuenta con una industria de componentes con un alto nivel de internacionalización, que exporta cada año más de 1.500 millones de euros a mercados exteriores. Además, más de 100 del total de empresas de CEAGA ya exportan sus productos o prestan sus servicios en el extranjero. Con el apoyo de la Xunta de Galicia, el Cluster de Empresas de Automoción de Galicia (CEAGA) fue fundado en 1997 por 37 empresas fabricantes de componentes de automoción, con el fin de desarrollar proyectos de carácter cooperativo orientados a la mejora competitiva. En noviembre de 2006 se creó la Fundación CEAGA, con el objetivo principal de “situar al Sector de Automoción de Galicia en una posición de liderazgo competitivo y sostenible en Europa en el Horizonte 2025, contribuyendo al progreso y a la calidad de vida de Galicia”. Actualmente CEAGA agrupa a la totalidad de empresas gallegas del sector industrial de automoción: más de 130 empresas proveedoras, el Centro de Vigo de Groupe PSA y el Centro Tecnológico de Automoción de Galicia (CTAG). -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

Barcelona 100 Years

Nº 2.339 ABRIL 2019 / 29 e .com LA PUBLICACIÓN DE LA INDUSTRIA DE AUTOMOCIÓN www.auto-revista.com @auto_revista AUTOMOBILE AÑOS BARCELONA 100 YEARS La edición “más eléctrica” The “most electric” edition CATALUÑA: RENOVACIÓN ANTE LA LOGÍSTICA CONECTADA SUBCONTRATACIÓN: RETOS LOCALES Y GLOBALES/ AUMENTA EN COMPLEJIDAD/ ENRIQUECIENDO LA CADENA CATALONIA: RENEWAL IN THE FACE CONNECTED LOGISTICS DE VALOR/SUBCONTRACTING: OF LOCAL AND GLOBAL CHALLENGES INCREASES IN COMPLEXITY ENRICHING THE VALUE CHAIN / Perfect Welding / Solar Energy / Perfect Charging TODOS TUS SISTEMAS DE SOLDADURA DE UN VISTAZO CON UN SOLO SOFTWARE ¿Cuál es tu reto ¡Visítanos en el stand L51– pabellón 5 en la feria Subcontratación! 4-6 Junio, Bilbao de soldadura? Let’s get connected. / Gracias a su amplia variedad de funciones, nuestro software Weldcube permite obtener datos y realizar completos análisis de líneas de producción enteras. ¿Cuál es el resultado? Mayor transparencia, seguridad y trazabilidad en la producción en serie. Además de verificar la calidad de soldadura, los datos obtenidos pueden ser usados para una continua optimización de los costes de tu empresa. Como resultado, se reduce el trabajo de supervisión y es posible dedicar más tiempo a la realización de otras tareas importantes. / Para más información, accede a: www.fronius.com/weldcube SUMARIO / IN THIS ISSUE Nº 2.339 / ABRIL 2019 CATALUÑA: RENOVACIÓN ANTE RETOS 19 LOCALES Y GLOBALES/Catalonia: renewal in the face of local and global challenges 47 LA LOGÍSTICA CONECTADA AUMENTA EN COMPLEJIDAD/Connected -

La Primera Crisis De SEAT: El Veto a General Motors Y La Compra De AUTHI a British Leyland (1972-1976)

IHE 9 (filmar) 18/11/07 19:09 Página 141 2007, otoño, número 9. Pp. 141 a 172 La primera crisis de SEAT: el veto a General Motors y la compra de AUTHI a British Leyland (1972-1976) The first crisis of SEAT: the veto to General Motors and the purchase of AUTHI to British Leyland (1972-1976) JORDI CATALAN VIDAL Universitat de Barcelona RESUMEN ABSTRACT En 1972 SEAT era la primera empresa In 1972 SEAT was the first Spanish industrial industrial hispana y lideraba la exportación firm and led the export of automobiles, de automóviles, gracias a una política thanks to a nationalist policy. However, the favorable a la nacionalización productiva. industrial policy of late Francoism Pero la política industrial del franquismo experienced a dramatic change with the tardío dio un giro copernicano con la approval of Ford’s decrees. Such a change aprobación de los decretos Ford. Dicho vuelco included the invitation to General Motors to incluyó, en 1973, la invitación a General Motors rescue the Spanish subsidiary of British a salvar la filial de British Leyland Motor Leyland Motor Corporation (BLMC), AUTHI, in Corporation (BLMC), AUTHI. Más que una 1973. The purchase of its plant in Landaben imposición gubernamental, la compra de by SEAT in 1975 has to be considered more Landaben por SEAT en 1975 constituyó la the consequence of a pact preventing the contrapartida del veto a la entrada de General entrance of General Motors than the outcome Motors. La resultante ampliación de plantilla of direct pressure by government. The era poco recomendable para una compañía increase in the size of employment resulted to que experimentaba un notable crecimiento de be a very risky decision for a company which costes laborales desde 1969 y una peligrosa was experiencing a significant push on labour caída de la demanda desde 1974. -

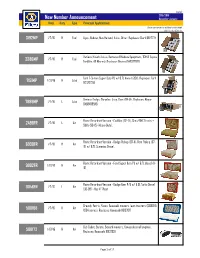

New Number Announcement December-January Date Duty Type Principal Applications Click on Part Number for Additional Product Detail

English 2015/2016 New Number Announcement December-January Date Duty Type Principal Applications Click on part number for additional product detail. *Added for Non-US Market. 3192MP 1/7/16 H Fuel Agco, Bobcat, New Holland, Volvo, Other. Replaces: Clark 6647774 Various Hitachi, Isuzu, Komatsu & Kubota Equipment, TCM & Toyota 3386MP 1/7/16 H Fuel Forklifts (10 Micron). Replaces: Nissan 16403Z7000 Ford F-Series Super Duty PU w/ 6.7L diesel (2011). Replaces: Ford 7151MP 1/21/16 H Lube BC3Z6731A Various Dodge, Chrysler, Jeep, Ram (08-15). Replaces: Mopar 7899MP 1/7/16 L Lube 04884899AB Flame Retardant Version - Cadillac (02-15), Chev/GMC Trucks + 2488FR 1/7/16 L Air SUVs (99-15) (Heavy Duty). Flame Retardant Version - Dodge Pickup (07-11), Ram Pickup (07- 6930FR 1/7/16 H Air 15) w/ 6.7L Cummins Diesel. Flame Retardant Version - Ford Super Duty PU w/ 6.7L diesel (11- 9902FR 1/13/16 H Air 16) Flame Retardant Version - Dodge Ram P/U w/ 5.9L Turbo Diesel 9946FR 1/7/16 L Air (03-09) - Has 4" Pleat. Gravely, Ferris, Yazoo, Kawasaki mowers, lawn tractors (X3000 & 500168 1/7/16 H Air X304 series). Replaces: Kawasaki 110137017 Cub Cadet, Encore, Exmark mowers, Kawasaki small engines. 500172 1/13/16 H Air Replaces: Kawasaki 110137031 Page 1 of 17 English 2015/2016 New Number Announcement December-January Date Duty Type Principal Applications Click on part number for additional product detail. *Added for Non-US Market. 200261 1/13/16 L Air Ford Fiesta (14-15). Replaces: Ford CN1Z9601A Ram ProMaster w/ 3.0L Diesel (14-15), Fiat Ducato, Peugeot, Other. -

Launch Issuemarch 2010

P001_ADEU_MAR10.qxp:Layout 1 4/3/10 19:02 Page 1 The pan-European magazine of the SAE International Launch issueMarch 2010 ■ Lightweight strategies under the microscope ■ Ford’s EcoBoost delivers 20% fuel savings ■ NVH Testing: sound engineering gets serious ■ Innovation and collaboration at SAE World Congress Lightweight champion. The all-new XJ fully exposed P002_ADEU_MAR10 3/3/10 11:49 Page 1 DUAL CLUTCH TRANSMISSION TECHNOLOGY IS MOVING THE INDUSTRY FORWARD. ARE YOU MOVING WITH IT? Maybe it’s the fact that in the time you read this, a Dual Clutch Transmission could switch gears 40,000 times. Perhaps it’s the fact that DCTs appeal to more buyers by combining impressive fuel-economy, the smooth ride of an automatic and the speed of a manual. It could be the fact that leading clutch suppliers estimate they’ll quadruple DCT sales by 2014. Or maybe it’s the fact that by 2015, 10% of all passenger cars will have them. DCTFACTS.COM gives you endless reasons to believe that DCTs are the future generation DCTFACTS.COM of transmissions. And the more you know about them, the further ahead you’ll get. P003_ADEU_MAR10.qxp:Layout 1 4/3/10 19:27 Page 3 Contents Vol.1 Issue.1 12 Cover feature 5 Comment Jaguar’s green technology Design Jaguar is synonymous with sporting elegance and collaboration will refinement – and now also high tech materials and drive recovery green endeavour. Ian Adcock gets the inside story from the all new XJ’s engineering design team 6 News 18 Spotlight on Phil Hodgkinson Performance hybrids Phil Hodgkinson talks with Ian Adcock about Jaguar Land Rover’s future engineering strategy Renault bids for 22 Engine technology CO2 leadership EcoBoost set to cut fuel consumption by 20% Ford’s EcoBoost is about more than cutting engine MultiAir set to capacity and adding direct injection, turbocharging grow and twin variable camshafts. -

Shirra Flashes Signs at TV

-v--,- ,? «, irtam the £f£scc»e#ecf nrocc . &5 A-QK' on Smoothest Space Fli ght ; News Roundup: From the State, Shirra Flashes Signs at TV ' SPACE CENTER , HOUSTON into the camera and laughing at Florida peninsula as it whipped asked mission control to "consider which causes residential lights to (AP) — Apollo7 Commander Wal- comments from the ground. None over it in 60 seconds. eliminating the chlorination of our Nation & World ter M. Schirra Jr., dim when heavy load appliances, wearing his of the three waved at the camera. Television transmission continued water today." such as air conditioners, are turned familiar lop-sided grin, greeted "You forgot to shave this morn- until the spacecraft passed over the Philadelphia Water on suddenly. The problem did not America from space with a joke ing, Eisele," Mission control said at horizon from Florida. Mission con- The astronauts periodically inject recur after the switch was reset. yesterday by televising a sign read- one point. trol said the final transmission chlorine into their water supply to The World ing Schirra and his crew seemed in a "Hello from the lovely Apollo came from about 800 to 900 miles assure its purity, but Schirra said it good mood entering the fourth day room , high atop everything." Lost His Razor Czech Workers Protest Soviet Pressure "I lost my razor," the Air Force from the Florida coast. took a period of time "before the of their 11-day, 41,2-million-mile Schirra. who refused to turn on Just over four hours after ' ' major replied. Astronauts cannot the water started tasting palatable flight. -

Pdf (Boe-A-1978-29328

PAGINA PAGINA MINISTERIO DE SANIDAD -Y SEGURIDAD SOCIAL Ayuntamiento de Gavá (Barcelona). Concurso para contratar los trabajos para la revisión del Régimen Delegación Provincial del Instituto Nacional de Previ catastral. 27118 sión en Guipúzcoa. Concurso de obras. 27116 Ayuntamiento de La Adrada (Avila). Subasta de ma deras. 27119 ADMINISTRACION LOCAL Ayuntamiento de Naquera (Valencia). Concurso-subasta Diputación Provincial de Ciudad Real. Concurso para de obras. 27119 adquisición e instalación de una central telefónica. 27116 Ayuntamiento de Puerto de Santa María (Cádiz). Con Diputación Foral de Alava. Concursos de obras. 27117 curso para contratar la explotación de unas canteras. 27119 Ayuntamiento dp Alacuás (Valencia). Subasta para Ayuntamiento de Puzol (Valencia). Concurso para. la contratar la recaudación de exacciones municipales. 27118 prestación del servicio de recogida de basuras. 27120 Ayuntamiento de Conil de la Frontera (Cádiz). Subasta Ayuntamiento, de Reus (Tarragona). Concursos de para enajenación de aprovechamiento de pinas de un obras, 27120 monte. 27718 Ayuntamiento de San Esteban del Valle (Avila) Subas Ayuntamiento de Chiclana de la Frontera (Cádiz). Con ta de obras. 27121 curso para la concesión del servicio de limpieza en Ayuntamiento de 'Segovia. Concurso para el suministro diversas instalaciones. 27118 de lámparas y material eléctrico. 27121 Otros anuncios (Páginas 27122 a 27134) I. Disposiciones generales Tercero.—Esta Orden entrará en vigor el día de su publica PRESIDENCIA DEL GOBIERNO ción en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado». Lo que comunico a VV. EE. Dios guarde a W. EE. 29327 ORDEN de 28 de noviembre de 1978 por la que se Madrid, 28 de noviembre de 1978. establecen los precios del azúcar producida en la OTERO NOVAS campaña 1978/79.