Brief Presented to the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security House of Commons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Register of Cultural Heritage Resources Designated Under the Ontario Heritage Act

Municipal Register of Cultural Heritage Resources Designated Under the Ontario Heritage Act Designated Properties Last Updated: 2021 1 Background In Ontario, the conservation of cultural heritage resources is considered a matter of public interest. Significant heritage resources must be conserved. The Ontario Heritage Act gives municipalities and the provincial government powers to preserve the heritage of Ontario. The primary focus of the Act is the protection of heritage buildings, cultural landscapes and archaeological sites. The Ontario Heritage Act enables municipalities to designate such properties if they hold “cultural heritage value or interest”. Municipal heritage designations are enacted by City Council through the passing of a by-law. Once a property is designated, it gains public recognition as well as a measure of protection from demolition or unsympathetic alteration. Designation helps guide future change to the property so that the cultural heritage value of the property can be maintained. There are two types of designation under the Ontario Heritage Act: designation of individual properties (known as Part IV designation), and designation of unique and important streetscapes, areas or "heritage conservation districts" (known as Part V designation). Any real property that has cultural heritage value or interest can be designated, including houses, barns, factories, cemeteries, parks, bridges, trees, gardens, hedgerows, fences, monuments, churches, woodlots, historic sites and the list goes on. Heritage designation is based on provincially regulated criteria (Ontario Heritage Act, O. Reg. 9/06), which includes design or physical value, historical or associative value, and/or contextual value. Heritage designation can be based on meeting one or more of these three broad criteria. -

PRISM::Advent3b2 8.25

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 39th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 39e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 1 No 1 Monday, April 3, 2006 Le lundi 3 avril 2006 11:00 a.m. 11 heures Today being the first day of the meeting of the First Session of Le Parlement se réunit aujourd'hui pour la première fois de la the 39th Parliament for the dispatch of business, Ms. Audrey première session de la 39e législature, pour l'expédition des O'Brien, Clerk of the House of Commons, Mr. Marc Bosc, Deputy affaires. Mme Audrey O'Brien, greffière de la Chambre des Clerk of the House of Commons, Mr. R. R. Walsh, Law Clerk and communes, M. Marc Bosc, sous-greffier de la Chambre des Parliamentary Counsel of the House of Commons, and Ms. Marie- communes, M. R. R. Walsh, légiste et conseiller parlementaire de Andrée Lajoie, Clerk Assistant of the House of Commons, la Chambre des communes, et Mme Marie-Andrée Lajoie, greffier Commissioners appointed per dedimus potestatem for the adjoint de la Chambre des communes, commissaires nommés en purpose of administering the oath to Members of the House of vertu d'une ordonnance, dedimus potestatem, pour faire prêter Commons, attending according to their duty, Ms. Audrey O'Brien serment aux députés de la Chambre des communes, sont présents laid upon the Table a list of the Members returned to serve in this dans l'exercice de leurs fonctions. Mme Audrey O'Brien dépose sur Parliament received by her as Clerk of the House of Commons le Bureau la liste des députés qui ont été proclamés élus au from and certified under the hand of Mr. -

City of Council Meeting Minutes

September 26, 2005 Regular Meeting – 1:00p.m. Council Chambers – 4th Floor Closed Session (See Item S) (Under Section 239 of the Municipal Act, RSO, 2001) Members: Mayor S. Fennell (left at 3:10 p.m.) Regional Councillor E. Moore – Wards 1 and 5 Regional Councillor S. DiMarco – Wards 3 and 4 (left at 3:10 p.m.) Regional Councillor P. Palleschi – Wards 2 and 6 Regional Councillor G. Miles – Wards 7 and 8 (left at 3:10 p.m.) Regional Councillor J. Sprovieri – Wards 9 and 10 City Councillor G. Gibson – Wards 1 and 5 (Acting Mayor after 3:10 p.m.) City Councillor J. Hutton – Wards 2 and 6 (left at 3:10 p.m.) City Councillor B. Callahan – Wards 3 and 4 City Councillor S. Hames – Wards 7 and 8 City Councillor G. Manning – Wards 9 and 10 (left at 3:10 p.m.) Absent: nil Staff: Mr. L. V. McCool, City Manager Mr. J. Corbett, Commissioner of Planning, Design and Development Mr. D. Cutajar, Commissioner of Economic Development and Public Relations Mr. T. Mulligan, Commissioner of Works and Transportation Mr. A. Ross, Commissioner of Finance and Treasurer Mr. J. Wright, Commissioner of Management and Administrative Services Ms. P. Wyger, Commissioner of Legal Services and City Solicitor Mr. L. J. Mikulich, City Clerk, Management and Administrative Services Ms. D. Pratt, Legislative Coordinator, Management and Administrative Services The meeting was called to order in Closed Session at 11:11 a.m., recessed and reconvened in Open Session at 11:23 a.m. to consider Resolution C243-2005 and moved back into Closed Session at 11:25 a.m., recessed for lunch at 12:20 p.m. -

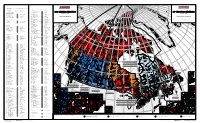

Map of Canada, Official Results of the 38Th General Election – PDF Format

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A nco co C Li in R L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol C A O N C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E !( e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T A I S Q Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I s In June 28, 2004 E T L 28 juin, 2004 É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I L R N D 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne a 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin E A n L N 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D P n d ely E n Gre 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin e t a s L S i U a R h A E XEL e RÉSULTATS OFFICIELS 10006 St. -

Core 1..44 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on Human Resources, Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities HUMA Ï NUMBER 030 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Tuesday, May 13, 2008 Chair Mr. Dean Allison Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1 Standing Committee on Human Resources, Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities Tuesday, May 13, 2008 Ï (0905) Canada's social security system, which is presently causing great [English] stress to seniors across Canada and to the families and communities to which they belong. The Vice-Chair (Mr. Michael Savage (Dartmouth—Cole Harbour, Lib.)): Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. All Canadians believe the elimination of poverty, especially I call the meeting to order pursuant to the order of reference of amongst those most vulnerable in society, should be the top concern Wednesday, November 28, 2007. We are studying Bill C-362, An of the Government of Canada. This bill will go a long way to Act to amend the Old Age Security Act (residency requirement). We alleviating the hardship experienced by some of Canada's most will be hearing from Colleen Beaumier, who has introduced that bill, vulnerable. from 9 to 10, and then from 10 to 11 we have a number of people Let me take a moment to explain how it will do this. The federal who have taken time to come and provide testimony on this piece of old age security program came into existence in 1952 as a matter of legislation. -

ENDORSED BY: Members of Parliament and Political Figures

ENDORSED BY: Members of Parliament and Political Figures 1. Flora MacDonald, former Foreign Minister of Canada 2. Carolyn Parrish (MP, Mississauga-Erindale, ON), Independent 3. David Kilgour (MP, Edmonton – Beaumont, AB), Independent 4. Andrew Telegdi (MP, Kitchener-Waterloo, ON), Liberal Party 5. Bonnie Brown (MP, Oakville, ON), Liberal Party 6. Colleen Beaumier (MP, Brampton West, ON), Liberal Party 7. Alexa McDonough (MP, Halifax, NS), NDP Foreign Affairs Critic 8. Bev Desjarlais (MP for Churchill, MB), NDP Critic for International Development 9. Bill Siksay (MP, Burnaby-Douglas, BC), NDP Critic for Citizenship and Immigration 10. Brian Masse, (MP, Windsor West, ON), NDP Industry Critic 11. David Christopherson (MP, Hamilton Centre, ON), NDP Labour Critic 12. Ed Broadbent (MP, Ottawa Centre, ON), NDP Critic for International Human Rights 13. Jack Layton (MP, Toronto-Danforth, ON), NDP Leader 14. Jean Crowder (MP, Nanaimo-Cowichan, BC) 15. Joe Comartin (MP, Windsor-Tecumseh, ON), NDP Critic for Justice 16. Judy Wasylycia-Leis (MP, Winnipeg North Centre, MB), NDP Finance Critic 17. Libby Davies (MP, Vancouver East, BC), NDP Housing and Multiculturalism Critic 18. Peter Julian (MP, Winnipeg North Centre, MB), NDP Finance Critic 19. Peter Stoffer (MP, Sackville—Eastern Shore, NS), NDP Veterans Affairs Critic 20. Yvon Godin (Député Acadie-Bathurst, QC), NDP 21. Daniel Turp (Député, Mercier, QC), Parti Quebecois 22. Inky Mark (MP, Dauphin-Swan River-Marquette, MB), Progressive Conservative Party 23. Warren Allmand, PC, OC, QC, former Solicitor-General of Canada 24. Councillor Dave Szollosy, Ward 3, (Orchard Beach - Jackson's Point)- Georgina, Keswick, Ontario 25. Pierre Laliberté, NDP Candidate, Hull-Aylmer, QC Law Organisations and Legal Professionals 1. -

Wednesday, May 8, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 042 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, May 8, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) OFFICIAL REPORT At page 2437 of Hansard Tuesday, May 7, 1996, under the heading ``Report of Auditor General'', the last paragraph should have started with Hon. Jane Stewart (Minister of National Revenue, Lib.): The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 2471 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, May 8, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [Translation] _______________ COAST GUARD Prayers Mrs. Christiane Gagnon (Québec, BQ): Mr. Speaker, another _______________ voice has been added to the general vehement objections to the Coast Guard fees the government is preparing to ram through. The Acting Speaker (Mr. Kilger): As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now sing O Canada, which will be led by the The Quebec urban community, which is directly affected, on hon. member for for Victoria—Haliburton. April 23 unanimously adopted a resolution demanding that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans reverse its decision and carry [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] out an in depth assessment of the economic impact of the various _____________________________________________ options. I am asking the government to halt this direct assault against the STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Quebec economy. I am asking the government to listen to the taxpayers, the municipal authorities and the economic stakehold- [English] ers. Perhaps an equitable solution can then be found. -

Computational Identification of Ideology In

Computational Identification of Ideology in Text: A Study of Canadian Parliamentary Debates Yaroslav Riabinin Dept. of Computer Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3G4, Canada February 23, 2009 In this study, we explore the task of classifying members of the 36th Cana- dian Parliament by ideology, which we approximate using party mem- bership. Earlier work has been done on data from the U.S. Congress by applying a popular supervised learning algorithm (Support Vector Ma- chines) to classify Senatorial speech, but the results were mediocre unless certain limiting assumptions were made. We adopt a similar approach and achieve good accuracy — up to 98% — without making the same as- sumptions. Our findings show that it is possible to use a bag-of-words model to distinguish members of opposing ideological classes based on English transcripts of their debates in the Canadian House of Commons. 1 Introduction Internet technology has empowered users to publish their own material on the web, allowing them to make the transition from readers to authors. For example, people are becoming increasingly accustomed to voicing their opinions regarding various prod- ucts and services on websites like Epinions.com and Amazon.com. Moreover, other users appear to be searching for these reviews and incorporating the information they acquire into their decision-making process during a purchase. This indicates that mod- 1 ern consumers are interested in more than just the facts — they want to know how other customers feel about the product, which is something that companies and manu- facturers cannot, or will not, provide on their own. -

Wednesday, December 6, 1995

CANADA VOLUME 133 S NUMBER 272 S 1st SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, December 6, 1995 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates and the Proceedings of Committee evidence are accessible on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 17271 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, December 6, 1995 The House met at 2 p.m. ment’s constitutional veto to provincial governments rather than the people, the government will pit one province against the _______________ others. Prayers The net effect of the government’s package is to increase inequality. Without a doubt, denying all citizens constitutional _______________ equality will entrench the notion that all Canadians are unequal. The Speaker: As is our custom, we will be led today in the My constituents in Edmonton—Strathcona and I support the singing of the national anthem by the hon. member for Kootenay Reform’s blue book policy which states clearly our commitment East. to Canada as one nation and to our vision of Canada as a [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national an- balanced federation of 10 equal provinces and citizens. them.] * * * _____________________________________________ SRI LANKA STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Ms. Colleen Beaumier (Brampton, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, Sri Lanka is a country consumed in violence by the ongoing conflict [English] between the Sri Lankan army and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. Since 1983, 50,000 people have been killed and another NATIONAL SAFE DRIVING WEEK 500,000 Tamils have been forced into exile. -

Canada and the New American Empire: War and Anti-War

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2004 Canada and the new American empire: war and anti-war University of Calgary Press "Canada and the new American empire: war and anti-war". George Melnyk, Editor. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2004. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49312 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com CANADA AND THE NEW AMERICAN EMPIRE edited by George Melnyk ISBN 978-1-55238-672-9 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration CIMM Ï NUMBER 026 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Tuesday, March 22, 2005 Chair The Honourable Andrew Telegdi All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1 Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration Tuesday, March 22, 2005 Ï (1105) For many years now AUCC has been actively engaged with key [English] federal departments on several issues related to Canada's knowledge economy and skilled workforce. We work closely with officials at The Chair (Hon. Andrew Telegdi (Kitchener—Waterloo, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, given the particular priority Lib.)): I would like to call the committee to order. We're going to placed by our member institutions on the effective facilitation of be hearing witnesses once again on the whole issue of international international students' entry into and stay in Canada for academic credentials. studies. We have with us, from the Association of Universities and Given the importance of the international student file, the Colleges of Canada, Madam Morris, who is president and CEO, and university community has long advocated that Canada needs to be Karen McBride; from the National Association of Pharmacy brought to a level playing field with regard to the recruitment of the Regulatory Authorities, Ken Potvin; from the Algonquin College best and brightest international students. A national approach to off- School of Health and Community Studies, Carmen Hust, Marlene campus work provisions for international students and the ongoing Tosh, Barbara Foulds, and Sylvie Lauzon; from the Ottawa reduction of permit processing times are central to this goal. -

Core 1..3 Journal

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 38th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 38e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 1 No 1 Monday, October 4, 2004 Le lundi 4 octobre 2004 11:00 a.m. 11 heures Today being the first day of the meeting of the First Session of Le Parlement se réunit aujourd'hui pour la première fois de la the 38th Parliament for the dispatch of business, Mr. William C. première session de la 38e législature, pour l'expédition des Corbett, Clerk of the House of Commons, Ms. Audrey O'Brien, affaires. M. William C. Corbett, greffier de la Chambre des Deputy Clerk of the House of Commons, Major-General Maurice communes, Mme Audrey O'Brien, sous-greffier de la Chambre des Gaston Cloutier, CMM, C.V.O., O.St.J., C.D., Sergeant-at-Arms of communes, le major-général Maurice Gaston Cloutier, CMM, C.V. the House of Commons, Mr. R. R. Walsh, Law Clerk and O., O.St.J., C.D., sergent d'armes de la Chambre des communes, Parliamentary Counsel of the House of Commons and Mr. Marc M. R. R. Walsh, légiste et conseiller parlementaire de la Chambre Bosc, Clerk Assistant of the House of Commons, Commissioners des communes et M. Marc Bosc, greffier adjoint de la Chambre des appointed per dedimus potestatem for the purpose of administering communes, commissaires nommés en vertu d'une ordonnance, the oath to Members of the House of Commons, attending dedimus potestatem, pour faire prêter serment aux députés de la according to their duty, Mr.